Amal Bhunia learned to fish with his grandfather in the Rupnarayan River when he was just 10 years old. Now 52, he still lives in the northeastern state of West Bengal, India, where he grew up. The fishing practices in his rural village in the Mahisadal subdivision—just 15 miles north of a cluster of petrochemical refineries in the port city of Haldia—have changed dramatically since his grandfather’s days, however.

“These rivers used to be so rich with fish that it was guaranteed that if you threw a net, you’d get some fish,” Bhunia said in Bengali through a translator. “But now there is no guarantee—except if you throw a net into the river now, you’re certain to get plastic.”

India is one of the world’s top producers of plastic waste, third in line behind the United States and China, according to a 2024 report from Swiss sustainability organization Earth Action (EA). Nearly 11 million tons of plastic waste are generated in the country each year. Indian leaders have struggled to manage this waste, resulting in plastic bottles, food wrappers, and tiny but alarmingly pervasive microplastic fragments polluting the waterways fishers traverse to satisfy their daily needs.

India isn’t alone. Plastics are a global crisis, and world leaders are finally taking action. In 2022, 175 country representatives came together in Nairobi, Kenya and agreed to draft a legally binding global agreement by the end of 2024 that would regulate plastics throughout their lifecycle.

That’s because plastics don’t just begin to cause harm once they’re in the trash. Nearly all plastics come from oil and gas. Producers heat these fossil fuels to separate their various chemical components and refine them into the products they need. This is how companies create toxic petrochemicals like ethylene and benzene, which then go on to become our sneakers or electronics.

Not only does this industrial process continue to emit planet-warming greenhouse gasses that have precipitated the climate crisis, but it also contaminates the air and water of nearby communities. Researchers are finally linking plastic exposure to health issues like reduced fertility and increased cancer risk. A report published this year found that at least 16,000 different chemicals are potentially used in plastics, about a quarter of which are known to be hazardous. Most others remain a mystery.

Bhunia has heard tales of his peers selling fish in the local market only to have customers return in a fury the next day, complaining about the putrid smell released after frying the fish. “It creates chaos in the market,” he said. In the fall and winter, he has seen the water levels near his village low enough to expose dead tangra, a tiny silver catfish, and hilsa, a gold-and-purple speckled relative of the herring.

He attributes these issues to the toxic byproducts released from the petrochemical refineries nearby in Haldia.

“I’ve seen some pitch-dark effluent coming into the water before, and it mixes with the mud-deep color of the water,” he said. “We can never catch fish in that area. Sometimes, we find them dead.”

If a global treaty is done right, it could offer dual relief to people like Bhunia: fewer plastics to clog up their gear and fewer contaminants to threaten their livelihoods.

On November 25, delegates from around the globe will gather in Korea to finalize the draft text of the world’s first global plastics treaty.

Or at least that’s the plan. The document would operate as the plastics equivalent of the Paris Agreement, the well-known climate accord intended to cut greenhouse gas emissions. Advocates working to influence the plastics treaty language have learned many lessons from the Paris Agreement, whose implementation requires consensus from all parties, meaning that all climate action by participants must essentially be voluntary.

It also means that “a small group of countries can have veto power over the rest of the world,” said Daniela Duran, a senior legal campaigner who works on the plastics treaty with the Center for International Environmental Law, which focuses on global law and policy.

Policy organizers don’t want the global plastics treaty to be another flop. Despite working toward establishing disaster-relief funding options for low-income nations, the U.N. climate conferences, or COPs, have failed to phase out fossil fuels thus far, and signatories have largely ignored their emissions reduction targets with little consequence.

The plastics treaty is encountering similar challenges: “We’re here negotiating the future of fossil fuels,” Duran said.

In April, the fossil fuel and chemical industry sent at least 196 lobbyists to the last treaty negotiating session. That’s more than the 180 people representing the entire European Union—and seven times more than the 28 representatives from the Indigenous People’s Caucus. Right now, plastics production is set to double or triple in size by 2050. If that happens, plastics alone could consume about a quarter of the planet’s remaining carbon budget by mid-century, all while bringing in major profits for the companies producing these products.

The 2022 U.N. resolution marking the promise of a treaty outlines several aspects of the plastics crisis that the global agreement should include: microplastics, marine pollution, the full life cycle of plastics, and possible alternatives to all the plastics that we use. The resolution also underscores the need for financial assistance to developing countries that can’t afford to manage plastic waste on their own.

If a global treaty is done right, it could offer dual relief to people like Bhunia: fewer plastics to clog up their gear and fewer contaminants to threaten their livelihoods.

Right now, delegates are focused on locking down the actual treaty language. From the perspective of many advocates who have been trying to inform delegates of their priorities, the language should address the root of the problem: plastics production. It’s been an uphill battle, as petrostates like Russia, Saudi Arabia, and Iran have been adamantly against such restrictions. India has been another vocal opponent. Now, the U.S. is pulling back its support for limiting plastics production, too.

“We absolutely need to restrict plastic at the source in order to, first of all, keep in line with the 1.5 degree Celsius target according to the Paris Accords and in order to avoid waste management systems—and our oceans and our biosphere—from becoming completely overwhelmed by all of these plastics and microplastics,” said Jamala Djinn, a policy adviser for Break Free From Plastic, a global coalition focused on the crisis. “The other aspect is the impacts to fenceline and frontline communities.”

Fisherfolk like Bhunia aren’t alone in their suffering. In the Arctic, remote populations are facing a dual crisis where their region is warming four times faster than the rest of the planet and experiencing increasing concentrations of microplastics in the sea. Native peoples who primarily fish and hunt wildlife for food face unique pathways of exposure given their relationship to the land.

“There is an urgency, and there are fundamental human rights [issues] associated with the impacts of plastics production,” said Pamela Miller, executive director of Alaska Community Action on Toxins, which partners with many Native Alaskan communities to fight against oil and gas expansion in the region.

Janelle Nahmabin, chief of the Aamjiwnaang First Nation, said that petrochemicals have been afflicting her people in Sarnia, Ontario, along the U.S.-Canada border near Detroit, for as long as she can remember. From outside her office window, she can see several refineries producing the chemicals that will eventually become plastics. She’s tired of it. “I’ve said these things numerous times, so forgive me,” she sighs over the phone.

Directed by Naguel Rivero; Camera + editing by Bautista Zelarayan Tobal

Nahmabin attended the most recent treaty negotiating session in Canada, where she met Indigenous peoples from countries like New Zealand and the Philippines. For the first time in a long time, she didn’t feel so alone.

“We all sat down, and people sang songs from their different countries,” she said. “Just hearing all of the different songs and all of their relationships to the land was so beautiful. That felt to me like a true nation-to-nation conversation.”

She wants to see a limit on plastics production—but it won’t be easy.

Some countries, including Pacific small island nations, welcome such ambitious regulations, but there isn’t a consensus. Environmental advocates want to see trade restrictions included that would prohibit countries that do not sign from exporting plastics to countries that do. This is how the U.N. implemented the Montreal Protocol, an international agreement that stands as an example of success in contrast to the failures of the Paris Agreement. The Montreal Protocol reduced the amount of ozone-depleting hydrofluorocarbons (or HFCs) being used by industry, and the ozone hole that was once the cause of global panic is healing as a result.

India, however, wants none of it—neither production limits nor trade provisions. Across the country, the private and public sectors are looking to add new petrochemical plants or expand old ones.

Back in Haldia, Haldia Petrochemicals Limited is actively constructing a major plastics plant in the city. It should be complete by 2026. Meanwhile, the state-owned Indian Oil Corporation has shared plans to develop its existing refinery in the city into a complex where plastic products are produced, too.

“In many cases, the communities do not have anything to gain from these types of development projects,” said Debasis Shyamal, president of the South Bengal fishing trade union Dakshinbanga Matsyajibi Forum, through a translator.

Shyamal is worried about the fishers he represents. Bhunia is scared for his future. He’s slowly seeing the fish population decrease and his peers abandon the sector altogether.

“Some days, I wonder if I should try something new,” he said. “But I’m too old now, and this is what I love.”

He used to find joy in going out into the water, sometimes journeying for days into the abundant mangrove ecosystem of the Sundarbans. He remembers the days when he’d pull in four-pound fish. Now, all he catches are plastic cups and bags and bottles.

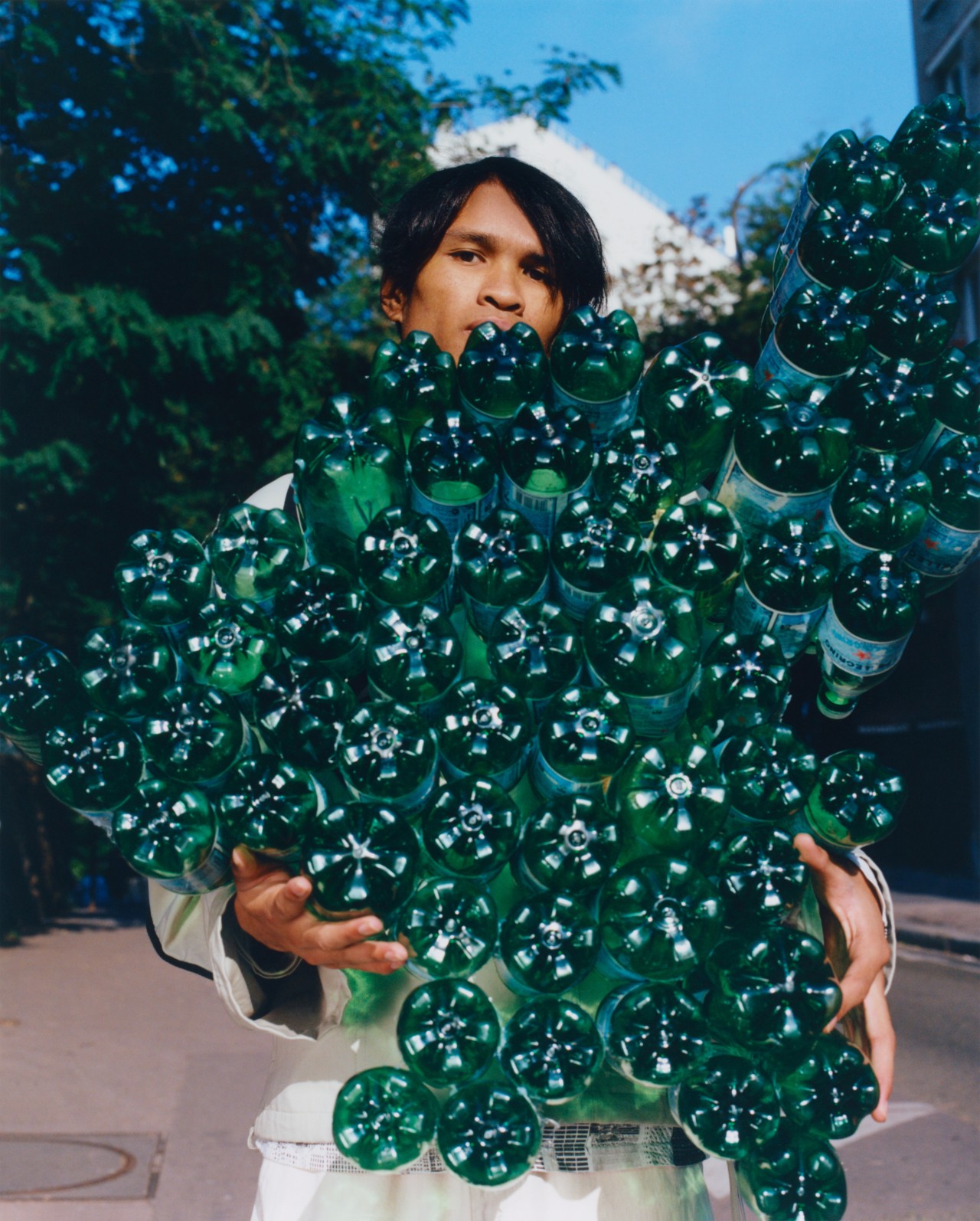

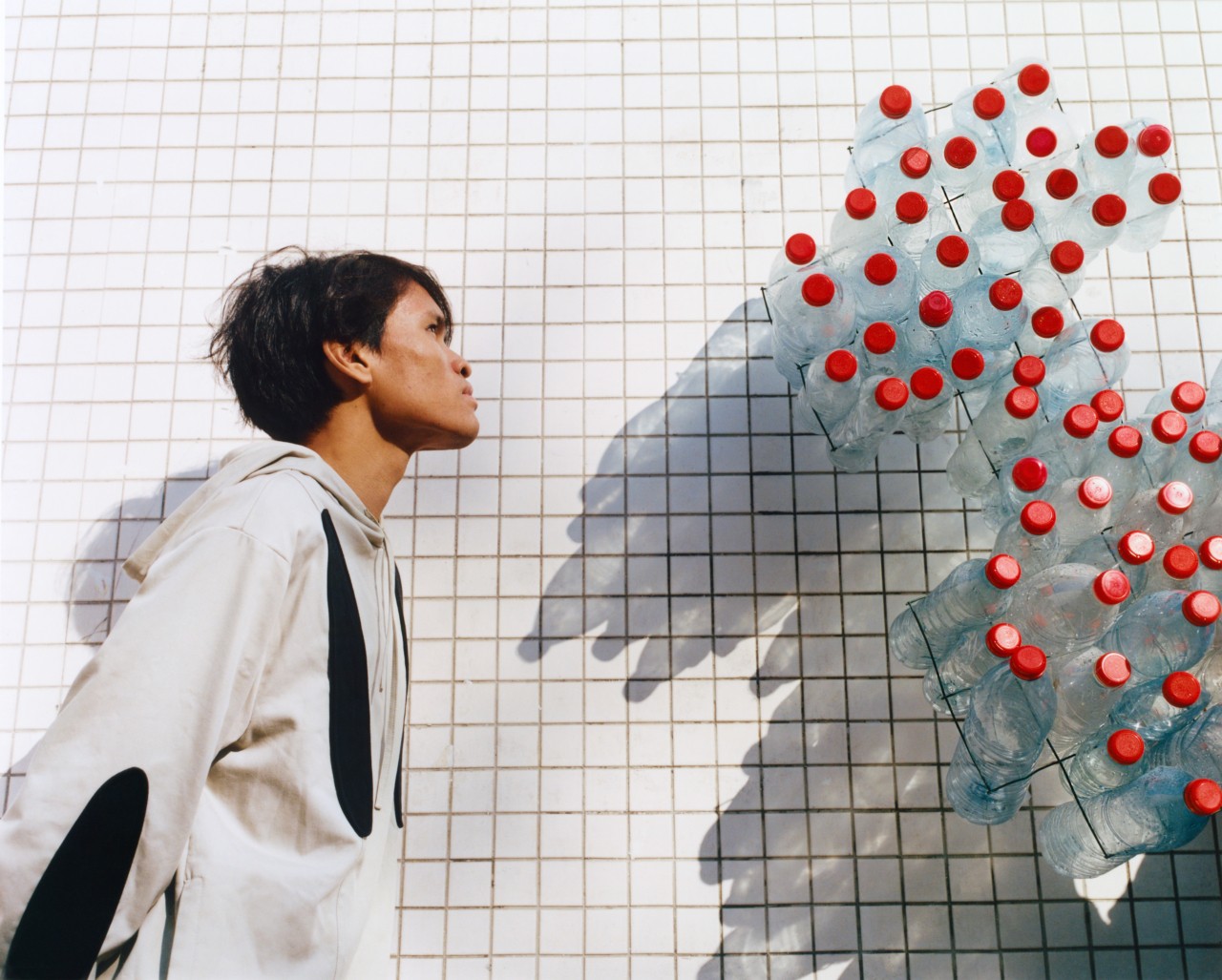

set design Pierre-Alexandre Fillaire talent Thomas Dussol, Anjara “Jaden” Rampanarivo, Aika (Blue Agency), Yaba (Kaba Casting), Marco Ribeiro casting Lylia Bokélé (Ikki Casting) executive production Rosie Donoghue (un/produced) production Casta Carola (un/produced) and Marguerite Vernier (un/produced) photography assistants Jean Sebastien Bubka and Blue production assistant Isabela Orozco (un/produced) post production Ale Jimenez special thanks Jordane from ERE collective, Marco Ribeiro, the whole team at Le Dorothy, Marie, Pascal, Alexis and all the artists, Guillaume, Joelle and Alain Lefevre, Olivia and the Douglas family

Dipanjan Sinha provided translation assistance for this article.

This story first appeared in Atmos Volume 10: Afterlife with the headline “Rapt in Plastic.”

The World Is Drowning In Plastic Pollution. Can a Global Treaty Fix It?