WORDS BY KATE FISHMAN

photographs by vivek vadoliya

Tāne Davis has dedicated two decades of his life to saving a flightless parrot known for its goofiness: the kākāpō. Fifty years ago, the bird was declared functionally extinct, driven into crisis by invasive and predatory rats, cats, dogs, and other mammals. For him, talking about kākāpō means talking about the history of New Zealand, or Aotearoa, as it’s called in Māori.

Davis lives at the southernmost end of Te Waipounamu, or New Zealand’s South Island, a 20-minute helicopter ride from a key breeding island for kākāpō. It’s the territory of the Ngāi Tahu iwi, or tribe, of which Davis is a member, and the first place in the nation where European whalers and sailors established colonial settlements after taking Māori lands, he said.

The iwi has always viewed its livelihood as intertwined with its nonhuman neighbors, including species seen as taonga, or treasured. Davis describes a connection to the land as “genetically built-in.” But centuries stripped of political sovereignty after colonization strained that relationship; when Davis first began representing the iwi as a member of the Kākāpō Recovery Group 19 years ago, the broader population didn’t know much about the “parrot of the night.”

“As an iwi, we were disconnected,” he explained. As the species marched closer towards extinction, Davis and his colleagues have worked to reconnect people with the lovable bird.

“When you’ve got a kākāpō which might die, how much effort do you put into stopping it from dying, and what does that mean for the wider population?”

Today, thanks to a creative conservation plan, there are 247 kākāpō alive—up from a low of 18 in the 1970s. This July, “for the first time in living memory,” biologists reintroduced four kākāpō to mainland New Zealand after the entire species was translocated to predator-free islands in the 1980s and 1990s. Each bird that breeds is a massive victory—and each one that dies is a bitter loss.

The plight of kākāpō is not unique. According to the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History, around 15,000 of an estimated 8 million species on the planet are at risk of disappearing. Some scientists have declared a sixth mass extinction. In a new study published earlier this week, researchers estimated that the genera of animals lost in the last five centuries would have taken 18,000 years to go extinct without human harm, concluding damningly that the “mutilation of the tree of life… is a serious threat to the stability of civilization.”

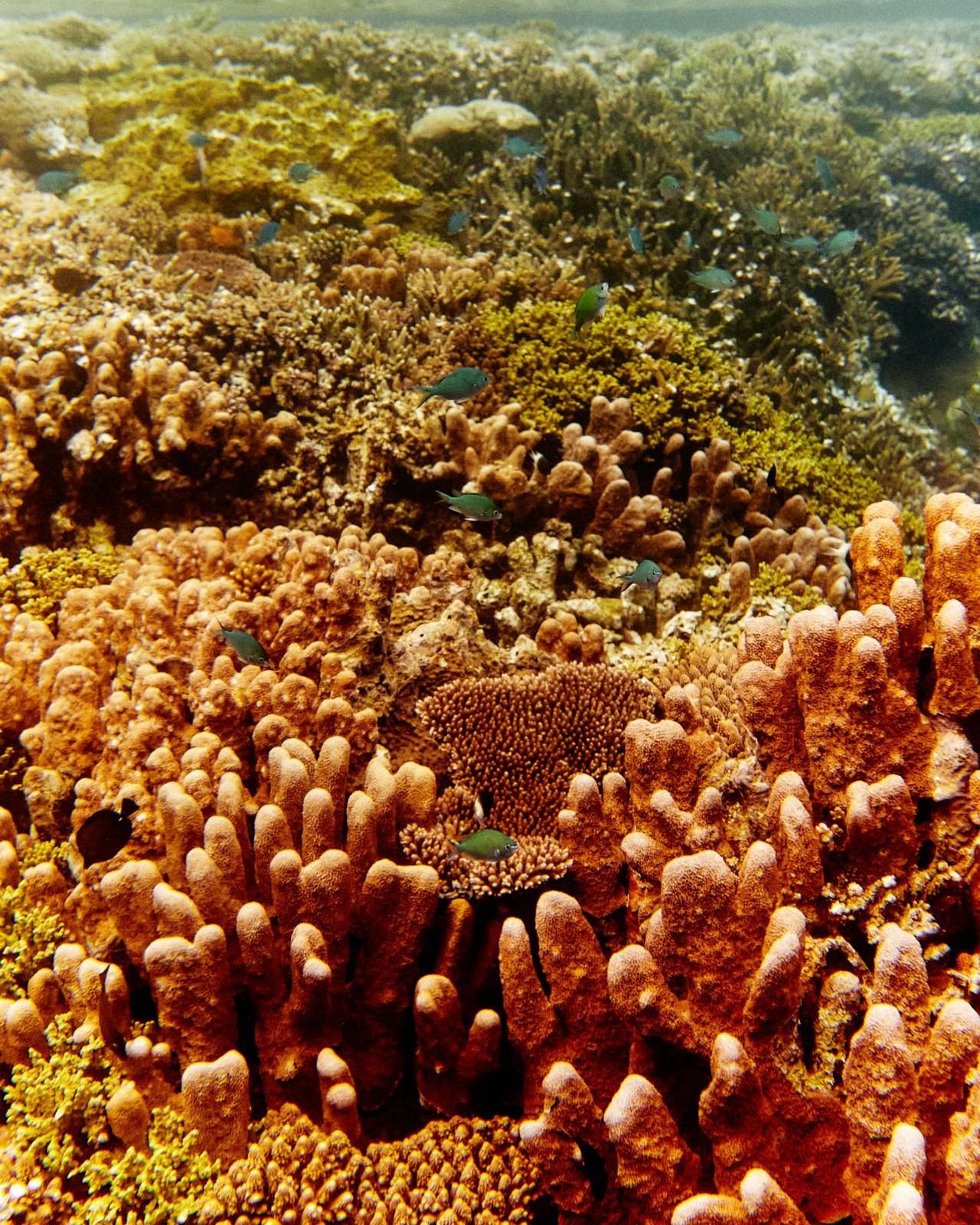

The vaquita, a small porpoise found in the Gulf of California, has plummeted from an estimated population of 567 in 1997 to less than 30 today. There are well below 50 Sumatran rhinos left. And this summer in the Florida Keys, when a dire marine heat wave bleached and killed many unique coral that populate the reefs, researchers feared that they were witnessing some species’ last days.

In reporting this story, I wanted to speak with people working to keep imperiled species here on Earth. I hoped to understand a feeling of precarity I couldn’t imagine. And while I did find grief and pressure, uncertainty and constrained resources, I also learned that no one wants to linger there too long.

“It’s going to continue to be difficult—and probably get more difficult—to do that science,” said Jason Spadaro, the manager of Mote Marine Laboratory’s Coral Reef Restoration Research Program. “I get up in the morning because I get to solve these very difficult problems.”

When populations are tiny and closely monitored, it’s natural to feel connected to specific individuals. Researchers often grieve the loss of animals they’ve gotten to know—but learning to detach is part of the job. It’s the way to keep the eye on the prize: the vitality of the entire species.

Every kākāpō has a name, said Andrew Digby of the New Zealand Department of Conservation.“We all have our favorites,” he quipped. “[But] we have to try and keep the population in mind and try not to be too concerned with the individuals—which is always a challenge. When you’ve got a kākāpō which might die, how much effort do you put into stopping it from dying, and what does that mean for the wider population?”

The same goes in the oceans. Susan Parks, who studies whale bioacoustics at Syracuse University, joked that some members of the North Atlantic Right Whale Consortium are “walking catalogs,” who can recognize any individual whale on sight. She can’t do that, but could recognize one male whale named Zebra when she was starting out as a graduate student, because of his distinctive white markings.

“I was like, Oh, well I like this whale, because I can see him from miles away and know who he is,” she recalled. “And he was never seen again after that year. So I learned pretty early on.”

North Atlantic right whales are experiencing an “unusual mortality event” thanks to ship strikes, entanglement in fishing lines, and dwindling food sources due to climate change. With around 350 still remaining in the wild, individuals stand out—but robust science is challenging.

“For North Atlantic right whales, some papers have taken the course of my entire career’s data collection to get a big enough sample size to start doing statistics,” Parks explained. “Looking at individual variability in calls took 15 years of data to get enough samples from enough individuals that we could compare them.”

The task of pulling a species back from the brink is daunting.

Studying the same individuals year after year, she said it can be easy to feel a relationship—though she’s not presuming that the whales recognize the research boats. Still, for both Parks and Digby, care for individuals is inevitably superseded by a deeper love for the uniqueness of the species as a whole.

Digby, for instance, is impressed by how easily kākāpō can climb from the forest floor to 30 feet up a tree and back again. They’re “this slightly endearing, sort of goofy creature which… people quickly learn to love,” he said.

He’s also impressed by their camouflage. Sometimes, he’ll know a parrot is feet away only by their scent. “It’s a fruity, musty, earthy sort of smell—very distinctive,” he described. “You can smell it from quite a long way away, and that’s with our useless human noses.”

Parks, too, loves learning about the mysterious lives of right whales.

“They’re large, long-lived mammals,” she said. “They have complex communication, they have complex social systems, but they live underwater out in the ocean.” The whales’ intelligence adds another layer to their plight—in Parks’ words, “It’s really heartbreaking if you think about the individuals and what they experience in this species.”

“There are some years that animals look really thin,” she said. “And there aren’t as many calves born because the females just don’t have the reserves they need to be successful in pregnancy…There’s just population decline and no way to recover.”

Parks’s work in studying whale communication has informed decisions around protected areas and marine policy that can offset sobering mortality rates. But you know there’s a way to go when a confirmed sighting of just one calf brought the biologist close to tears.

The task of pulling a species back from the brink is daunting. Taking it one step at a time often also means big, confident steps; many researchers and conservation managers pursue fascinating innovations in attempts to address risks to these populations.

Kākāpō, for example, may be the planet’s most heavily and creatively managed species. Every bird has been outfitted with a “personal Fitbit” that they wear like a backpack. During their sporadic breeding seasons, which depend on the fruiting of specific plants like the rimu tree, kākāpō sometimes access personalized feeding stations which open only for one specific individual.

Māori people have formulated a family tree for all living kākāpō based on genetics research. Celebrating “star” kākāpō like Sirocco, the national “spokesbird” for conservation, has also reacquainted New Zealand residents of all backgrounds with the unique bird. The entire arsenal of solutions has been crucial to the population upswing the species has seen in recent years.

While kākāpō conservation has chugged along over decades, coral reefs in Key West faced a make-or-break period of days when water temperatures soared above 100°F this summer.

After monitoring the rising temperature risks over a month, inside of a week Spadaro from the Mote Marine Laboratory and more than 70 full-time staff evacuated thousands of coral from Mote’s offshore nurseries in a massive “genetic banking effort.” No species experienced extinction or extirpation, Spadaro reported, but the Keys have seen a “strong reduction in the abundance of all of the different species of coral.”

As intense as this summer was, Spadaro feels its challenges provided valuable information to increase the longevity of the 18 coral species they were already actively working to restore.

“Those corals that remain have gone through one of the most powerful selective forces that we’ve seen on Florida’s coral reef,” he said. “Thus, they are among the fittest individuals that we could potentially select for restoration.”

“We all do come together with something in common, and it’s mauri: It’s the life force.”

His team practices resilience-based restoration, meaning that their breeding programs work to both bolster genetic diversity and increase adaptive traits to known threats like ocean acidification, heating temperatures, algae overgrowth, and disease.

One technique they use is called refragmentation. Essentially, it’s cloning. By cutting a tiny fragment of one coral using a jeweler’s bandsaw, the coral’s cells kick into a healing response. Once outplanted, these small, regenerating coral fragments grow between 40 and 50 times faster than a typical coral; and when they meet and recognize their genetic likeness, they fuse.

“In a slow-growing, massive, reef-building species, we can go from outplanting those fragments on the reef to having a reproductive colony in three to five years,” Spadaro said.

Genetics-based solutions like these are becoming more common as researchers stare down the biodiversity crisis, according to Erich Jarvis, chair of the Vertebrate Genomes Project (VGP).

“There are going to be many, many more of these near-extinct or extinct species within our lifetime,” he said. “I’m distinguishing less between those that are still around and those that are gone than I would have normally, before.”

Jarvis, who primarily researches vocal learning in birds, came to VGP because he wanted more resources to sequence the genetic code of the species he loves to study. But as he pursued more accurate genomic sequencing methods with a coalition of other scientists, he was asked to chair VGP and expanded its goal to document the genomes of all 70,000 vertebrates on the planet. He sees initiatives like these as the “morally responsible” way to keep pursuing his scientific fascinations.

“One day using sequence data alone we could resurrect species, or still learn something about the natural order of life,” Jarvis explained. “We have that data in a database that we purposely call GenomeArk, to save as many of the species’ genomic data as possible before they’re gone.”

Davis of the Kākāpō Recovery Group connects all different iwi with scientists from Western backgrounds, working to find population management solutions for kākāpō that will account for needs and sensitivities on each side. He describes the years of dialogue as “a really interesting journey.”

“We all do come together with something in common, and it’s mauri: It’s the life force,” he maintained. “We came to the same understanding of why we wanted to integrate the two sciences. We wanted to make sure the species didn’t go into extinction.”

In his work, Davis has helped to conserve a variety of other species around the islands, too. Those who study our most imperiled organisms are uniquely equipped to understand ecological balance.

“There’s a school of thought that says you shouldn’t be putting so much effort into those charismatic species,” Digby said. “But what we do is very ecosystem focused. For example, all of these islands that kākāpō are now on, most of them were actually made [invasive] predator-free in these sanctuaries to put kākāpō there. The primary goal is to protect kākāpō, but obviously all those other species that live on those islands benefit, too.”

On Digby’s best days, working with kākāpō is a hopeful look toward the future.

“The males in the summer and the breeding seasons have this deep booming call, which you kind of feel rather than hear—it’s pretty low frequency,” he described. “It’s pretty amazing to be on an island off the coast of New Zealand, surrounded by a million seabirds, and hear kākāpō booming. It’s a real taste of what New Zealand used to be like—and a little bit of a flavor of what it could be like one day again.”

For researchers like Digby, grappling with biodiversity loss for a living does not lend itself to hopelessness. On the contrary: When you spend your days trying to keep a species alive, no matter how fervently you’re taught to decouple your heart from your head, you tend to love your job.

The Scientists Studying the Edge of Extinction