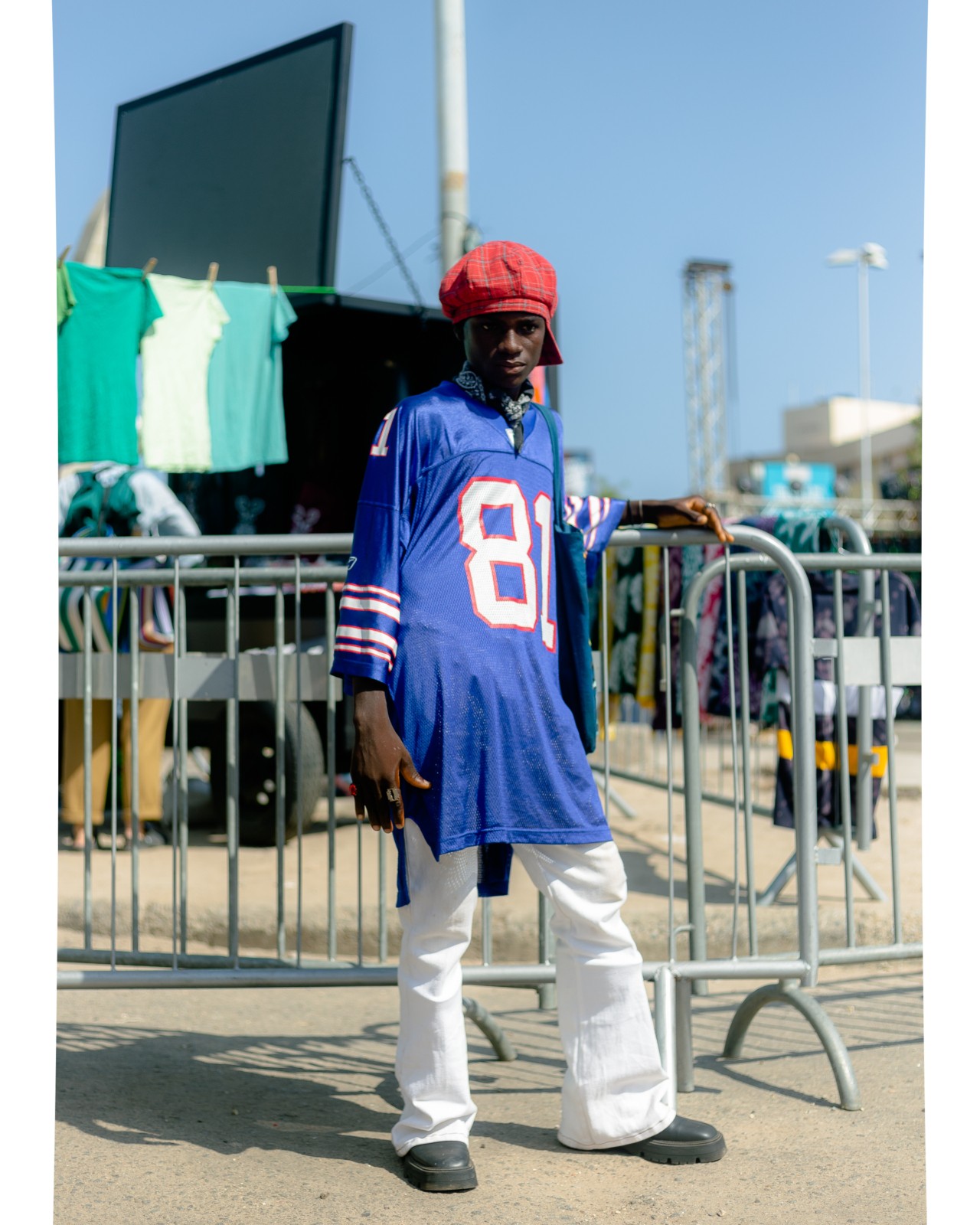

Photograph by Sackitey Tesa

Words by Elvis Kachi

photographs by Sackitey Tesa Mate-Kodjo, Komla S. Darku, Elroy Salam

Countries in the Global South have long borne the brunt of global waste management systems that are built on injustice.

Among them is Ghana, a country that in just one week, imports up to 15 million used garments, about 40% of which end up as waste. It’s no surprise, then, that landfills across the country are brimming with mountains of discarded textiles, often mixed with household, chemical and even medical waste, as local communities struggle to process the scale of rubbish that is being sent to them from countries in primarily Western Europe and the U.S.

But in the heart of Ghana lies the Kantamanto Market where a quiet sustainable revolution is underway. At first, Kantamanto, a market in Accra that has become known for its eclectic offering of used garments and textiles, appears like any other hub of commerce at the center of the fashion industry’s waste crisis. In reality, however, it has become a symbol of resilience and transformation—a space where throwaway garments are repurposed and given new life.

Helping Ghanaians challenge the systems that perpetuate and reinforce waste colonialism is The Or Foundation—a public charity in the U.S. and a registered charity in Ghana— which over the years has become a guiding light for the creation of a thriving resale economy. Records show that over 30,000 vendors at Kantamanto, traders, and retailers are turning a profit from the secondhand garments that come into the country through nearby ports. Many of them, with the help of The Or Foundation.

The Or Foundation’s approach is multi-pronged: No More Fast Fashion Lab is a community center and circularity lab adjacent to Kantamanto Market aimed at providing circular product design and skills training to local upcyclers, but the charity also works to support those most affected by the West’s culture of excess. Last year, for instance, the nonprofit teamed up with and showcased the Owo Designers, a group of designers who source materials from the Kantamanto market to produce fashion collections that are later presented, distributed, and sold across the country and globally.

“We’ve seen these young emerging designers who do not have any ‘formal background’ in fashion, and our next line of thought was how to elevate this craft, since they have already been creating really interesting designs from the available materials,” Eugene Ewusi-Annan, program research and implementation assistant at The Or Foundation, tells Atmos. “This is one of our major missions, and it is essentially to elevate and bring to a more global audience the works of these incredible designers. [The designers are] still in awe at how very interested in what they’re doing the world is.”

The Or Foundation’s commitment to sustainability extends far beyond the market. Workshops and outreach programs are framed to engage the broader fashion community, raising awareness about the industry’s unjust power dynamics, the environmental impact of fast fashion, and the transformative potential of upcycling. It has grown to become a collective effort to redefine the fashion landscape—one where designers are not just creating for the sake of production and excess, but conscious contributors to positive change.

For a number of these designers, the discovery of the Kantamanto market could be likened to accessing a treasure trove. Take Charles Doziah, for example, the owner of Xtreet Guidance, who has been running a stall at Kantamanto market with his uncle since he was 19 years old. His time at Kantamanto was what sparked his interest in upcycling and recycling garments—and he was good at it, too. He would spend days taking apart discarded designs from the ever-flowing wells of deadstock fabrics, and remodelling them into something wearable. But being a part of The Or Foundation’s training program—which includes workshops on branding, garment construction, customer acquisition, and garment care—has allowed him the chance to experiment with a wider range of textiles, including denim, a fabric that is notoriously difficult to handle. The end result includes experimental patch works unlike anything he had made before.

“The hope in being a part of this initiative is that I grow much larger, and effect a positive change within my community.”

Doziah’s goal for Xtreet Guidance goes further than Instagrammable visuals and trendy lookbooks. He wants to drive economic growth not just for himself, but for his peers, too. “The hope in being a part of this initiative is that I grow much larger, and effect a positive change within my community,” Doziah says.

Felix Wahab Owusu, the creative director of Oldy Blaq, shares a similar story of self-realization and self-reliance. “My collection, Mmrzovdafutr, was inspired by how humans are destroying our planet. There’s just too much waste and not enough justice,” Wahab tells Atmos. From woven butterfly wings to insect-inspired burlap dresses, his conceptual designs reference the mutual symbiosis between all living creatures on Earth. “I want people to recognize how their activities have the power to positively or negatively impact the environment,” he says. “And I try to use my designs to be carriers of such a message.”

As The Or Foundation mentors and trains the next generation of upcyclers, they instil not only technical expertise in them, but also the spirit of entrepreneurship. “With the Sender Receiver residency program, which is built on the idea of the Global North sending waste to the Global South, we brought together students from The Netherlands, the U.K., and Ghana, and they were made to work on a contribution project that spoke to their environmental and entrepreneurial drive, through a waste to wealth directive,” Ewusi-Annan says, referencing the organization’s localized attempts at redressing historical imbalances of power.

As with many of her peers, the designs of Rebecca Naa Korkor Mensah, founder of fashion brand Nakoi, are often political. Operating under neocolonial trade agreements as a sustainable designer means even her choice of materials—like the big chequered nylon bags, infamously nicknamed Ghana Must Go—points to the systemic challenges that both drive and reinforce the waste crisis. “I wanted to use this collection to talk about some things that’s been happening in my life,” she tells Atmos. “And I also wanted to use this collection to teach young women on the importance of turning lemons to lemonade.”

In the system of waste colonialism, it is all too often women who carry the load—in Accra, this means moving materials between Kantamanto market and nearby landfills, and sorting through piles of waste to determine what is, and is not, usable. The risk of severe injury from the 120-pound bales they balance on their heads cannot be overstated. And it’s why Mensah uses her designs to shine light on the experience of women in the fashion space.

In her most recent collection, for instance, Mensah references the discriminatory Tignon Laws that forced women of African descent in the U.S. to conceal their hair to prevent them from attracting the attention of white men in the 1700s. Mensah’s designs, which are made from recycled materials and polypropylene, are adorned with the silhouettes of women wearing head wraps—an homage to those who suffered under the Tignon Laws and those who, today, even under the harshest of circumstances, continue to uphold the fashion industry.

The reality is that Ghana’s waste trade is still very much booming. Colonial power structures have established a pattern where the Global North continues to wield economic influence over the Global South—and in Ghana’s case, these economic disparities are driving the flow of discarded materials from affluent nations to the communities surrounding Kantamanto.

In a bid to fight against and rebalance these power dynamics, governmental policies in countries like Uganda, for example, have put in place nationwide bans on the importation of used clothing from countries in the Global North. Though these, too, have been criticized by local designers for not doing enough to support local communities of craftspeople. “What The Or Foundation seeks in terms of working with the government is the awareness of the global EPR,” Ewusi-Annan says. “If policies that enable brands to be accountable and conscious of their manufacture, production and sustainability choices, then that will make a difference to the problem we see of receiving almost 15 million garments every week.”

“I want people to recognize how their activities have the power to positively or negatively impact the environment. And I try to use my designs to be carriers of such a message.”

The problem of imported waste is so huge that local designers’ determination to create beauty from trash is nothing short of revolutionary; an act of resistance against the waste crisis that has taken over much of Ghana’s landscapes.

One such designer is Antydote founder Emmanuel Tetteh, who created his latest collection from garments sourced exclusively from Kantamanto. “Working with The Or Foundation to produce [these designs] is definitely a dream come true,” he says. “For me, finding a focal point for the capsule collection was a challenge—and even when I did, translating it to designs also challenged me.” In navigating through personal hurdles, he consulted with the leaders of the classes he attended, who helped him maneuver through the blocks.

The end goal for The Or Foundation alongside its community of collaborators—of local designers and craftspeople—is clear. “For us, the focus is on how to support the people in the Kantamanto Market, especially because there are no jurisdictions or policies [to combat waste colonialism] by the government to provide some form of safety net for those in the informal sector like the designers,” Ewusi-Annan says. Offering practical skills-building, and emphasizing entrepreneurship and resourcefulness through workshops, is just one piece of the puzzle The Or Foundation is working tirelessly to assemble.

Ultimately, however, it’s the designers they mentor who are redefining the narrative of the fashion in Kantamanto Market with a shared vision for a more equitable and sustainable future—one stitch at a time.

In Ghana, Training Local Upcyclers at Kantamanto Market