Words by Omnia Saed

Photographs by Denisse Ariana Pérez

On a quiet Monday in December, I stand before Senegal’s famed Lake Retba, better known as Lac Rose. I had expected its signature mauve and scarlet-pink waters, but am instead met with dark, murky hues. The parking lot feels abandoned, sparsely dotted with stalls for a handful of tourist vendors. Lightly dusted with sand, sellers’ wares sit unnoticed as their hopeful gazes track every passerby. “It’s a weekday,” a boat guide offers with a shrug, as if timing alone could explain the absence of visitors: Senegal’s peak tourist season runs from November to March.

The lake’s faded color—once its most captivating feature—now hints at a deeper and more complicated story.

Located about 21 miles from Dakar and separated from the Atlantic Ocean by narrow dunes, Lake Retba owes its iconic pink hue to Dunaliella salina, a salt-loving microalga that thrives in hypersaline waters. This microorganism produces a red pigment to absorb sunlight, enabling the algae to generate energy in the lake’s extreme salinity. Lake Retba’s salinity reaches up to 40% salt in some areas, with concentrations rivaling the Dead Sea. When sunlight is strongest and evaporation rates are highest during the dry season, the lake transforms into its most vivid pink to create a surreal scene where visitors can float with ease due to the water’s extreme buoyancy. This natural marvel has attracted tourists from around the globe for decades, cementing its place as one of Senegal’s top attractions and a recurring contender for UNESCO World Heritage status.

In recent years, however, the lake’s once-vivid pink hues have faded, giving way to murky shades of gray and black. Mére Kiné Thiam, 67, has spent her entire life by the lake and witnessed its shifting colors over the decades. She sells bracelets and handcrafted jewelry to tourists to support her family, though she admits that business has become more challenging. “Something comes, and something goes,” she said, her voice a blend of resignation and quiet hope. When asked if she believes the lake’s vibrant color will return, she shrugs. “Only God knows. Everything else is beyond us.”

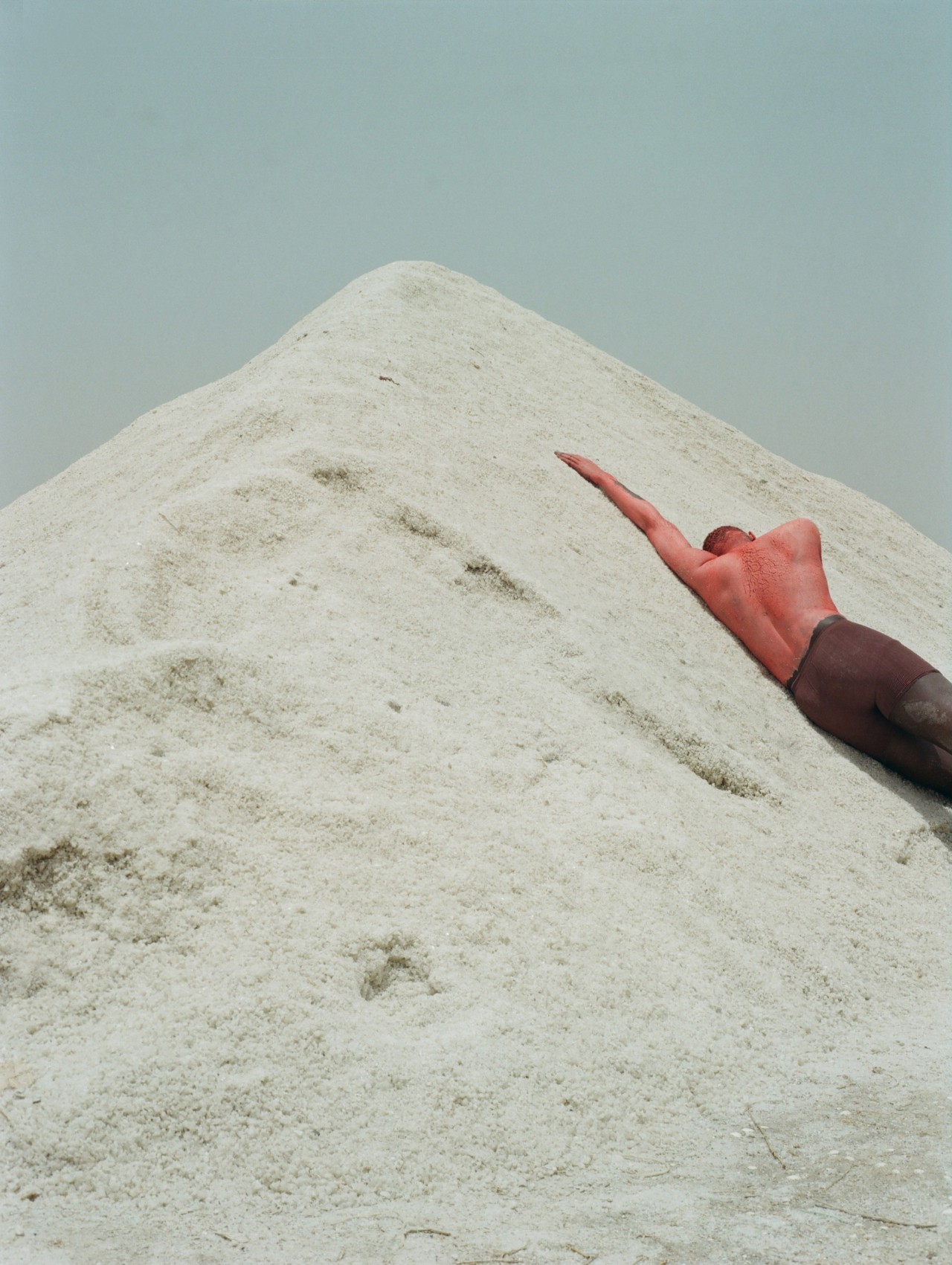

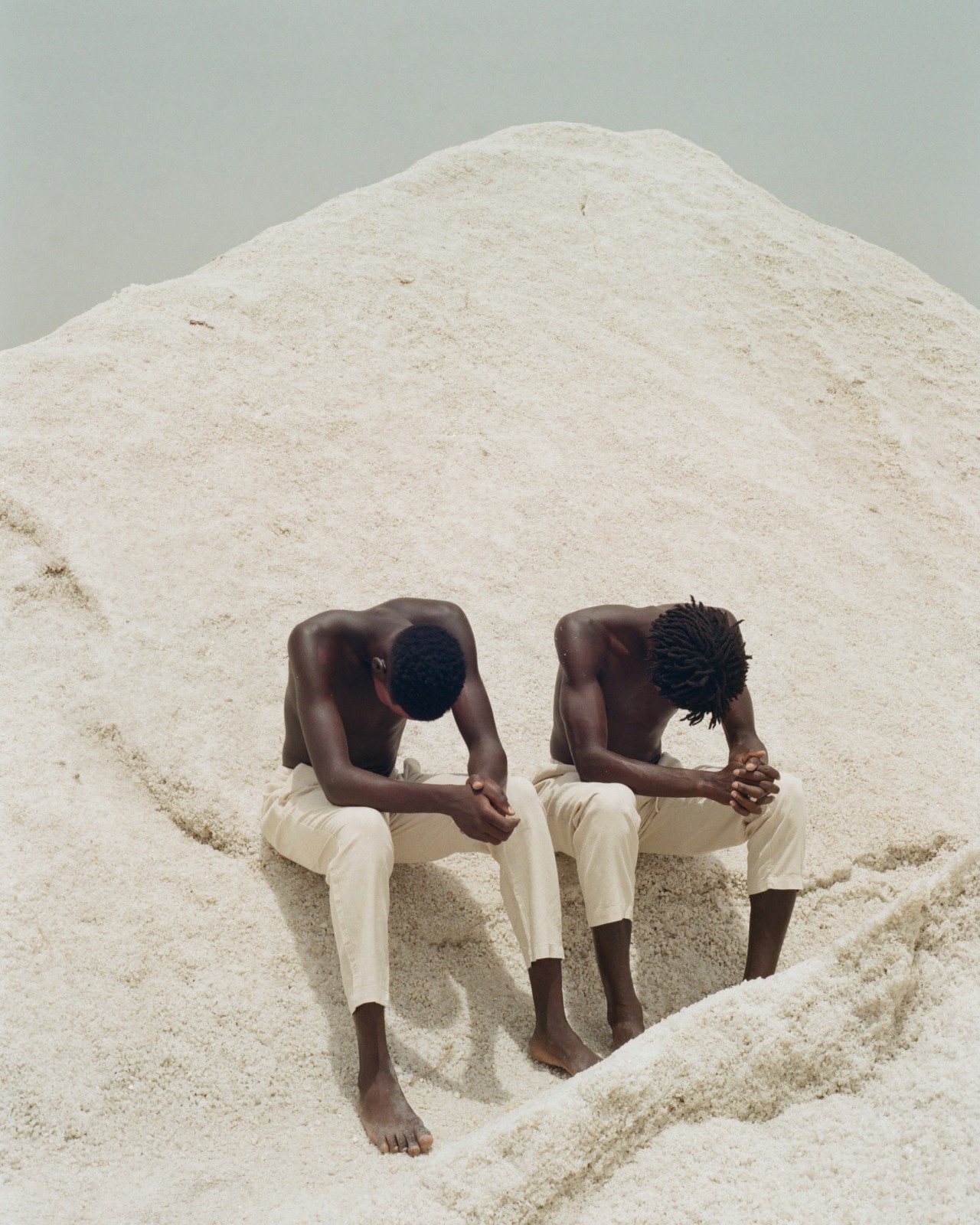

For locals like Mére, the lake is more than just a natural wonder: It’s a lifeline. Artisanal salt mining has long been a cornerstone of the local economy, employing an estimated 1,500 to 3,000 people. Senegal, the largest salt producer in Africa, depends heavily on Lac Rose. In 2010, the lake produced approximately 140,000 tons of salt annually, approximately one-third of the 450,000 tons the country produces every year, which is then distributed across the country and neighboring nations. The glittering white salt mounds, rising starkly against the horizon, have defined the landscape for decades.

But as the lake’s ecosystem falters, its ability to sustain the livelihoods of those who rely on it is increasingly under threat.

As the lake’s ecosystem falters, its ability to sustain the livelihoods of those who rely on it is increasingly under threat.

El Hadji Sow, a professor at the Department of Geology at Cheikh Anta Diop University, has studied these changes for years. In his office, Sow explains that the lake’s transformation began roughly four decades ago. His research focuses on the interplay between salinity, sediment inflows, and diatoms—small algae that serve as a food source for marine organisms. By examining diatom fossils and sediment samples, Sow reconstructs the environmental history of Lac Rose and warns of the grave and growing consequences for its delicate ecosystem.

Rising wastewater, pollution, and sedimentation pose significant risks to the lake, Sow said, with potential consequences for the salt it produces. Contrary to popular belief, he notes, salt extraction itself has not harmed the lake’s survival; it actually helps prevent the depression from filling up entirely. Rather, it’s the pollution—exacerbated by factors like agricultural runoff and untreated wastewater—that renders the salt unfit for consumption. This, in turn, prohibits its extraction and causes an accumulation of unusable salt combined with sediment from the relief canal that could fill the depression. Within a few years, Lac Rose as we know it could disappear.

The catastrophic floods of 2022 underscored these vulnerabilities. Torrential rains in August and September caused widespread flooding in Dakar and surrounding areas, breaching the lake’s banks and washing away 7,000 tons of harvested salt: an estimated loss of 420 million CFA francs ($696,000), according to the Lake Retba Salt Extractors Association. The floodwaters erased months of labor and disrupted the lake’s delicate equilibrium, raising fears about the sustainability of future salt harvests.

The intensity of 2022’s rainy season was found by Senegal’s National Agency for Civil Aviation and Meteorology to be consistent with the findings of the United Nations’ report that year on climate change. Without immediate intervention, Lake Retba’s ecological and economic futures hang precariously in the balance.

Ibrahim Diouce, 31, a local who has lived and traveled abroad, pulls out his phone to show me a photo of the lake at its peak pink. We’re sitting in a canoe, drifting across waters now murky green and black. “Hard to believe this is the same place, isn’t it?” he said with a laugh of disbelief. “We call the lake Retba. Retba means ‘welcome’ or ‘arrival’ in Pulaar,” he added, the name a bittersweet reminder of what it once represented. He points to new developments along the shore: vacation homes and rentals built by wealthy Senegalese and retirees, many from France. “Here is better,” he said with a quiet irony. “It’s better than Europe for them.”

The irony isn’t lost on the local community, for whom life by the lake has grown increasingly difficult. The rapid, unregulated urbanization of the northern shoreline has led to rising nitrate levels, primarily from hotel developments and the lack of a proper sewage system. Polluted runoff flows into the lake, altering its chemical makeup and contaminating the salt that artisanal miners depend on. For Ibrahim, the lake’s transformation is a bittersweet reminder of home and change. “Sometimes I feel like the future will be hard,” he said, his voice steady but reflective. “But I always come back.”

While locals grapple with these changes, the question of intervention looms large. Efforts to preserve the lake are sporadic at best, with limited government initiatives and a lack of robust environmental regulations. UNESCO’s consideration of Lac Rose as a World Heritage Site offers a glimmer of hope, but even that designation wouldn’t immediately address the pollution or urbanization. What’s needed, experts argue, is a comprehensive approach that balances tourism, urban growth, and environmental preservation.

As the sun sets over Lac Rose, its waters glimmer faintly, hinting at the pink hues buried beneath. For locals like Ibrahim and Mére, the lake is more than just a source of livelihood—it’s a witness. Whether the lake’s vibrant colors will return is uncertain, but for now, they hold onto the belief that something comes, and something goes.

How Senegal’s Iconic Pink Lake Lost Its Hue