Photograph by Hyoung Chang / Getty Images

WORDS BY EMMA RUBIN

Ashley Roberson attended every football game her son, Remy Hidalgo, played as an offensive lineman for Denham Springs High School near Baton Rouge, Louisiana. She often watched practices from her car, and September 15, 2020, was no different. It was a hot day—typical for Louisiana that time of year—and even hotter on the turf field.

Hidalgo, a high school junior who bounced between starter and backup in previous seasons, loved football since he was 4 years old. This year, he wanted to be a lineup lock. “The mentality of this is if they don’t do their best and work the hardest and prove themselves, they won’t get their starting position,” Roberson said.

As the team ran laps toward the end of practice, the coach noticed Hidalgo slow down and fall behind his teammates. The coach pulled him off to check in; Hidalgo deflected with a joke and tried to rejoin his teammates, but was sent inside to rest. As he walked back to the locker room, people heard Hidalgo talking incoherently. Roberson said witnesses told her his last words were, “Don’t cut me, coach.” Then, he collapsed.

Roberson had left practice earlier to pick up her daughters from cheer practice. When she got back home, she got a call that Hidalgo had passed out and immediately rushed back. She remembers seeing him with his eyes rolled back as he lay unconscious in the ambulance, and she screamed the whole ride accompanying him to the hospital.

Hidalgo was hospitalized for three days. On September 18, 2020, he died from exertional heat stroke.

Sixty-seven high school student-athletes in the United States died from EHS between 1982 and 2022, the majority of them football players. Heat policies aren’t controversial for athletic trainers, but few states mandate comprehensive guidelines for schools.

“Remy was a healthy kid. He never had any problems. He hardly was ever sick. His death is not just a thing that happened. It’s going to continue to happen if we are not educated on it.”

Douglas Casa has advocated for better high school sport safety policies for 15 years as the CEO of the Korey Stringer Institute. He said getting schools to adopt heat-safety policies hasn’t been easy. “Most states do it after there’s a death,” he said. “But you don’t have to have a heatstroke death to have heatstroke policies.”

These policies include adjusting practice when heat and humidity surpass safety thresholds and having a coldwater immersion tub on site. Casa said state associations are moving faster to implement these measures than they were when he first started, but he still faces resistance—even as heat becomes more intense.

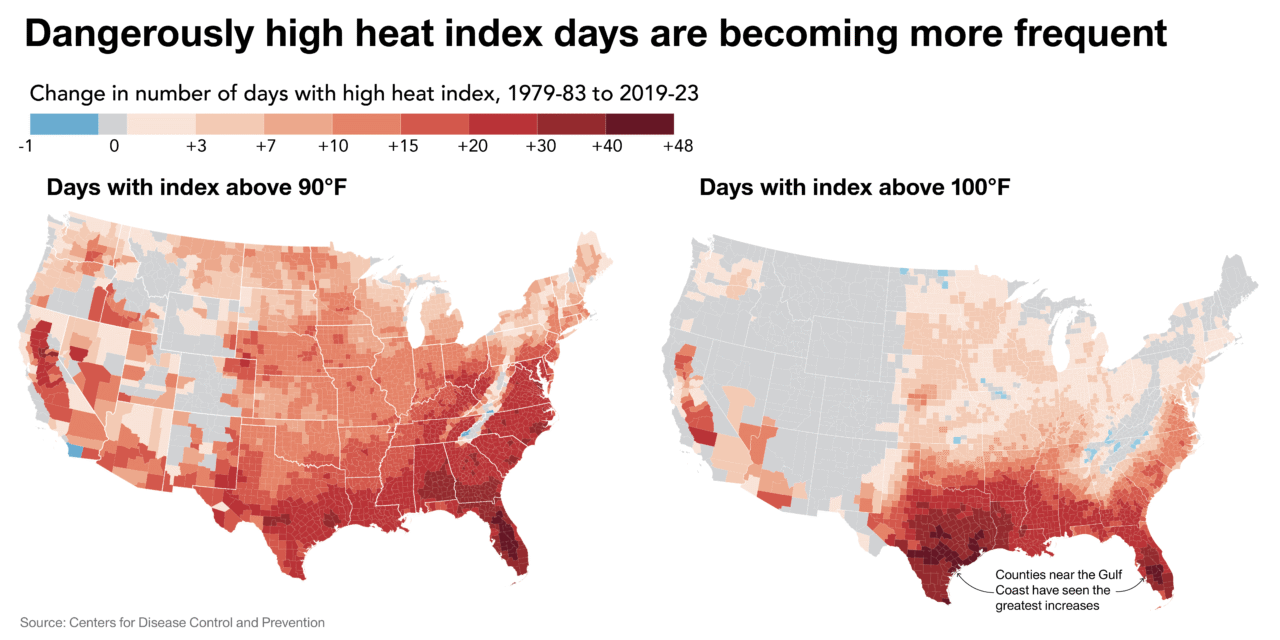

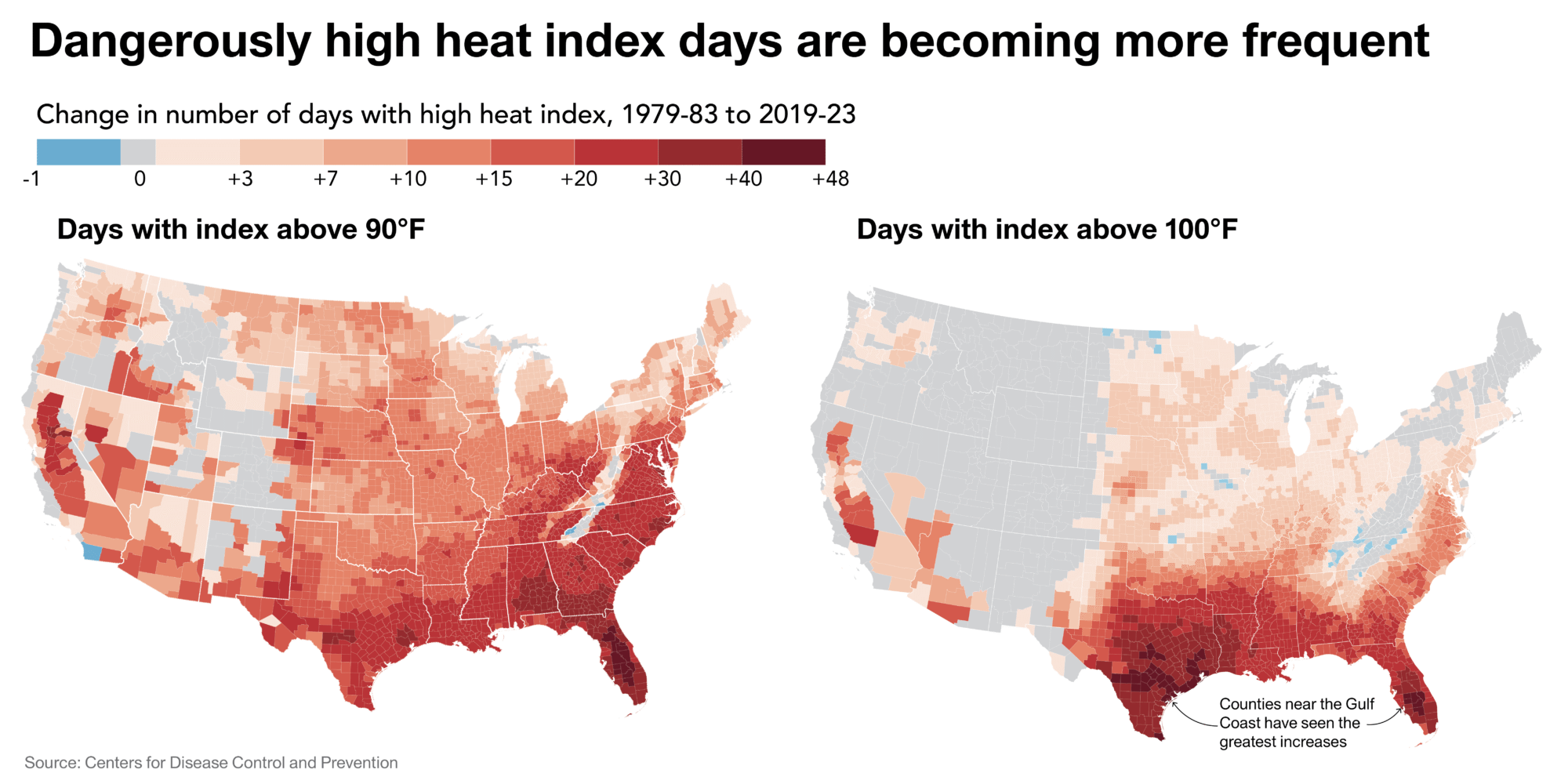

Most heat stroke deaths in the U.S. occur in the Southeast. But EHS happens across the country, and the risk is threatening student-athletes in more states as climate change exacerbates heat waves—especially in regions where high school football is most popular, and including those with less comprehensive policies in place.

“I think 25 years from now, high school football will be a spring sport instead of a fall sport,” Casa said. “Then we would be gearing up 300-pound linemen in full gear for five hours of practice in a day in March instead of August.”

Most counties in the U.S. experience more high heat index days than they did 40 years ago. Heat strokes become possible above a 90-degree Fahrenheit heat index, and the “danger” zone begins at 103 degrees; areas as far north as the Midwest now face about 10 dangerous days per year.

The gold standard for assessing heat risk, however, is using a wet-bulb globe temperature reader. These remote-like instruments calculate a metric based on solar radiation, ambient heat, and humidity. Unlike the heat index, the wet-bulb measure is hyperlocal, based on playing in the sun rather than the shade, and does not make assumptions about height and body mass.

More schools today require WGBT readers in their heat policies. But in Texas, where some counties record the highest number of high heat index days in the country, WGBT readers are recommended—not required.

“I’ve been in a few different states, and I just really think that the high school athletics and culture of athletics here in Texas is just so much different than anywhere else,” said Tiffany Phillips, an athletic trainer at Grapevine High School near Dallas. Eight of the nation’s 10 most expensive football stadiums are in Texas, per USA Today. The state also has one of the highest football participation rates in the country.

Phillips, who also chairs the Southwest Athletic Trainers’ Association’s Secondary School Committee, said there has been some frustration among coaches since the state’s sports association first started recommending WBGT rules for football practice. Coaches aren’t sure what to do when WBGT readings fluctuate in and out of caution zones. Like many heat modification guidelines, the recommendation only applies to practices, as games have water breaks built into them, and substitutes can provide breaks for players. Some coaches have questioned how they can prepare for games in the heat if they can’t practice in it.

In Phillips’ case, varsity and junior varsity football practices occur in the morning and end by 8:45 a.m. Grapevine coaches also have access to a 60-yard indoor facility where they can practice on hot days, but not every high school has that luxury.

“I really feel like if they change the wording from recommended to required, and more schools and athletic directors and coaches see that this is a mandate, I think we would have across the board more buy-in to it,” said Phillips. “Whether they liked it or not, they would do it because that’s the rule.”

Amy Wiggins, an athletic trainer in Massachusetts, remembers being on call for a girl’s lacrosse game when a player from the opposing team went down. “She didn’t complain about anything. She had no cramps. There was no call,” she said. Still, when she saw the player’s flushed skin and how she ran in the wrong direction as she fell, Wiggins knew right away it was heat-related.

“I was looking for this because I felt it was a hot day … but it is hard for those who don’t have an athletic trainer.”

About one-third of public schools don’t have athletic trainers, according to the National Association of Athletic Trainers. Research shows low-income schools are most likely to lack access to trainers, and that employing trainers is linked to fewer fatalities and injuries. For Wiggins, this gap underscores the importance of having clear guidelines and educating coaches. “We need policies, procedures, and emergency action plans,” she said, and those emergency plans must be rehearsed each season, like fire drills.

At Denham Springs High School, Roberson later learned that best practices weren’t followed the day of Hidalgo’s heat stroke. The team had water breaks, but they weren’t mandatory; plus, Hidalgo was not immersed in a cold water tub for enough time to bring his core body temperature down to the safe range below 102 degrees.

After Hidalgo passed away, Roberson advocated for a Louisiana law in his name. Passed just ahead of the 2021 football season, the Remy Hidalgo Act mandates that schools have emergency action plans, including defined emergency cooling procedures that could have saved Hidalgo’s life. Louisiana, Florida, and Georgia are among the states with the most robust heat policies.

Today, Roberson runs the Remy Hidalgo Foundation, which distributes cold tubs to schools across the state. She still hears from trainers and parents familiar with her son’s story and who now know to look out for signs of heat stroke.

“Remy was a healthy kid. He never had any problems. He hardly was ever sick,” she said. “[His death] is not just a thing that happened. It’s going to continue to happen if we are not educated on it.”

This article was made possible with support from the International Center for Journalists’ News Corp Media Fellowship program.

High School Football Isn’t Ready for More Extreme Heat