WORDS BY TONY TEKARONIAKE EVANS

ARTWORK BY MER YOUNG

It feels different driving across the big lonely of Southeast Idaho these days. I’m en route to the Tetons, a toothy little snag on the distant sunrise horizon that marks the southern boundary of Yellowstone National Park. Little packs of pronghorn antelope stand idly in the desert, designed to outrun predators that died out during the Pleistocene. People were here back then, too.

It feels different because Deb Haaland, an Indigenous Pueblo woman, is now in charge of the U.S. Department of the Interior, which oversees nearly 12 million acres of Bureau of Land Management lands in Idaho and 245 million acres total, about 10% of America’s land surface. At the National Park Service, Charles Sams III, an Indigenous Cayuse and Walla Walla man, is the new director. Yellowstone (where I’m headed) is the world’s first national park—and perhaps the most famous one. Sams now oversees all the 423 national parks that cover over 85 million acres of public lands.

It feels different these days—not just Dances With Wolves different—but epochal: Standing Rock to seat-at-the-table different. In a monumental event, Yellowstone National Park has invited representatives from the tribal nations with traditional uses and habitation in the park to the table—many of whom are part of the Land Back Movement to return stolen lands. This event takes place at a time when the country and the wider world are looking to Indigenous people for direction.

The White House, for instance, sent out a press release last year elevating Indigenous traditional ecological knowledge in federal land use decision-making. I got the press release at my small-town news desk and read it to find the words “biological,” “cultural,” and “spiritual” all in the same sentence in reference to the future of “environmental sustainability.” Sheer desperation over looming ecological catastrophe, including the climate crisis, has led to an all-hands-on-deck moment, me thinks. Old traditions are crossing the boundary between science and religion to shine in a new light.

Documentary filmmaker Ken Burns once called national parks “America’s best idea.” Teddy Roosevelt envisioned a project that would set aside natural wonders for the public—wonders that would rival the great cathedrals and palaces of Europe. But this great plan left out an important element: the keystone species called human beings who had hunted and gathered, traded, and socialized in places like Yellowstone since time immemorial. These people were excluded from such U.S. parks, public lands, and “wilderness areas” generations ago.

Roosevelt was an unabashed racist and fan of the notion that so-called “white” people with Judeo-Christian worldviews should rule the world. How surprising would it be for him to know that 150 years later, Indigenous people are in the vanguard of conservation movements that could save this weary planet from destruction? Roosevelt once said: “I don’t go so far as to think that the only good Indian is the dead Indian. But I believe nine out of every 10 are, and I shouldn’t like to inquire too closely into the case of the 10th.”

“We are using the 150th anniversary of Yellowstone to point out that Native Americans have been on this land for more than 10,000 years before the park came into existence.”

A persistent but false rumor followed the establishment of Yellowstone in 1872—that Native Americans had avoided these steamy, fumarole, and geyser-spewing meadows and forests due to superstition. I’ve also heard that rumors from that time said Indians would soon go extinct. I think of these rumors as I interview Yellowstone National Park Superintendent Cameron Sholly beside a row of tipis at Yellowstone’s Madison Junction in August. He’s here to experience some of the events associated with Yellowstone Revealed, a long overdue program of Indigenous culture-sharing from the 27 tribal nations (at least though some say up to 49) that once called this place home. The events are also a focal point for the Land Back Movement that is catching on around the globe, rematriating traditional lands to Indigenous people.

“What’s it been like to work with all these tribes in preparation for this?” I ask Sholly.

“It’s been a privilege—and an inspiration,” he said. “But this is only a start. Just a beginning for us. We are using the 150th anniversary of Yellowstone to point out that Native Americans have been on this land for more than 10,000 years before the park came into existence.”

Sholly has come to realize just how important this place has been to Native Americans. “It’s one thing for the Park Service to instruct visitors about the Native American history of Yellowstone,” he said. “It’s something else entirely to have people from these tribes interact directly with the park visitors.”

Hence the tipis, where tribal representatives are busily interacting with passersby, one of whom wants to know if Indians still live all year in tipis. “No, they only get used in summer,” said a tall man in a cowboy hat, wearing shell earrings. “We live in houses. I use a chainsaw when I get firewood. See that red truck up there. It’s mine.”

Roosevelt’s inferiority complex with regard to European cathedral architecture drew attention to the awe-inspiring American landscape and yielded an idea that caught on; there are now 1,200 national parks in over 100 countries around the world. They all have Indigenous stories of some kind or another. Europe’s only Indigenous people—the Sámi—inhabit areas in Finland, Norway, and Sweden. Much of their territory is protected by national parks. Columbia has 51 national parks across a wide range of ecozones, including many areas reserved for Indigenous people.

Formidable institutions such as the Ford Foundation and the United Nations now recognize that the best way to preserve biodiversity on this planet would be to protect the 370 million people inhabiting the most biodiverse areas. Lifeways that engender reciprocity and natural land stewardship are the results of thousands of years of cultural imperatives. From New Zealand to Idaho, for instance, Indigenous people are working to bestow personhood on rivers.

Back in Yellowstone, the land seems Edenic despite the steady flow of summer tourist traffic. Ducks and geese appear fearless in the Firehole River. A buffalo—how many Native folks refer to the North American bison—wanders carelessly between cars on the highway. The park’s 3,472 square miles are home to up to 5,500 of America’s last remaining wild buffalo. Yellowstone is primarily a driving tour park that exalts the peculiar majesty, beauty, and power of this place. The sight of tipis draws many motorists off the road and down to the river confluence at Madison Junction for teachings.

There, I meet Wes Martel, a 20-year veteran of the Eastern Shoshone Business Council at the Wind River Reservation in Wyoming. He patiently explains to tourists the ins and outs of water law, how Indians hold senior water rights west of the Mississippi, and how Europeans laid claim to North America under a “Christian doctrine of domination.”

“They regarded us as pagans and, therefore, subhuman,” Martel said. When the tourists move on, Martel tells me that “land back” for him is reflected in the ongoing effort at Wind River to reclaim more than 110,000 acres of land, only a portion of the 331,000 prime northside acres that non-Indians took and settled on when the rez was opened to homesteaders by the U.S. government the early 1900s.

“Our culture is based on reciprocity. For us, it’s crazy to think that we have this land inside this fence, and it’s not yours.”

“That is land that is supposed to come back to us,” he said. “We also need to educate our young people about how to breathe life back into our treaties in order to strengthen our communities.”

I like meeting new people, but I’m already missing my wife and my little red house in Idaho’s Wood River Valley and the old growth lawn with its tangle of weeds, dried dandelions, grasses, and now, the late summer clover and mysterious unidentified ground cover. My bucket of Three Sisters, or “Our Life Supporters,” are wrapped in their tangled and storied embrace. The corn provides a stalk for the beans to climb up on, who provide shade for the squash growing underneath. It’s more than just a complete protein—in the same way the Land Back Movement is about more than real estate.

I guess Land Back’s meaning depends on the kind of Indian you are. The Dine’ (Navajo) have more than 17 million acres of land, but 30% of their nearly 400,000 tribal members lack running water and reliable electricity. Our First Nations Mohawk reserve of Kahnawake in Quebec, Canada, is said to be the size of a postage stamp. In 2018, it was enlarged by 500 acres near my mother’s land. The Onondaga Nation, keepers of the grand council of the Iroquois Confederacy, recently got back 1,000 acres in New York.

Some Indians live in hogans in the desert—others in the swamp or in the tundra. Mohawks build skyscrapers. Some tan skins and make warm gloves, like my Agai’Dika-Shoshone friend Leo Arriwite. He showed me a 100-mile reservation near Salmon, Idaho, that was taken from his people before they were marched to Fort Hall, Idaho, in 1907. Many people died en route. They want the land back.

From 1776 to 1887, the U.S. government took over 1.5 billion acres of Indian land. The latest iteration of Land Back was jump-started recently in Lakota country, home to Mount Rushmore in their sacred Black Hills. Along with Roosevelt’s face in stone there, you have a Francophile owner of enslaved people named Thomas Jefferson; honest Abe Lincoln, who presided over the largest public execution (38 Indians) following the Dakota War; and George Washington. We have a name for Washington in Mohawk that stems from the American Revolution; it translates to “village destroyer.” No wonder the brave Lakota Land Backers showed up and got arrested protesting President Donald Trump’s entourage visit. They aim to shut down Mount Rushmore’s white supremacist idolatry once and for all.

The community of Indigenous people in the U.S. is 574 nations strong. Some were created deep underground; some came into existence on islands off the coast of California. Some emerged from Wind Cave in South Dakota. We didn’t come here alone, us hapless human beings. We had allies in the spirit and animal worlds. My wife, a Tuscarora and also Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) like me, came from people who fell through a hole in the Sky World and landed on the back of a turtle. My wife works on IT support for hydrothermal plants and power lines. Looks to me like she might be running the Starship Enterprise. Indians will one day travel to distant galaxies, you’ll see—but first, we must save the world.

As I sit by her tipi in Yellowstone, Nona Longknife, a Nakoda grandmother from Fort Belknap in Montana, tells me about Indigenous perspectives. She sang her morning song under nearby cliffs a day prior and felt “the power of these mountains,” as she put it. She said “land back” isn’t just about getting a paper giving title to land.

“To be with the last wild buffalo makes this home for me,” she said. “To be free to walk wherever we want to. It’s OK again to be who we are here. We are connected again to what this world has to give, not just to the small square of our reservation, which is the same as a [prisoner of war] camp.”

Longknife said the whole concept of land ownership is foreign to her: “Our culture is based on reciprocity. For us, it’s crazy to think that we have this land inside this fence, and it’s not yours. We give first and ask permission for what we take. We tell the tobacco that we want to use you in this way. We pray when the sun comes up—for guidance and for the sun to warm us.”

“The Earth is our greatest mother and our greatest teacher,” Longknife went on. “She has taken care of us for thousands of years. Indigenous perspectives are important for the wider world because we are in a phase of change. You can’t separate people from the Earth. Look where that has taken us… Take, take, take. We always had the concept of sharing because we all need one another. It’s important for people to see us for who we are, not how we have been portrayed in books for self-serving gains.”

All the years of sacrifice, fasting, and prayers have led to this day in Yellowstone, Longknife said. For me, it looks like the first national park is finally regaining its soul.

“Our young people are able to be here and are allowed to let this happen,” she said. “To present our culture and language. People are coming here to get something they can’t get anywhere else. It makes me proud.”

With so many Indians from different nations in one place, connections emerge. I speak with a Northern Cheyenne man named Burt Medicine Bull. He shows me the wild turnips, rose hips, and chamomile tea that his people gathered in the park. He lit some cedar in a clamshell and told me how the Lightning and Thunder spirits were always so mischievous. A cedar tree once caught a lightning bolt and wouldn’t let it go until it promised to light cedar smoke as a medicine. “Lightning agreed, and so now we know cedar smoke is even more powerful than Lightning,” said Medicine Bull, whose family often lights cedar in the morning.

Medicine Bull has a bowl with seeds: the Three Sisters of corn, beans, and squash. They are familiar to the Mohawks, I tell him, but I never knew they were grown out this far northwest. He tells me that the Three Sisters came to the Northern Cheyenne from a spirit grandmother: “Some young warriors were out hunting and heard a voice singing behind a waterfall. They went behind the waterfall and found a grandmother singing. She had three bowls. In one was corn, beans, and squash. She told the story of how to grow them together. But we didn’t take care of that ceremony for the corn, so we lost the corn.”

I talk about the Mohawk story of how these three crops came from the body of a woman and about the great wrestling match at the dawn of Creation. We talk about Muskrat, who for us brought land to Turtle’s back and created the world. He said the Northern Cheyenne refer to Muskrat as “the showoff.” We laugh. Showoff indeed! Bringing the world into existence and all. But of course, world creation was a group effort by many creatures, none of which were told to hold dominion over the rest.

“The Earth is our greatest mother and our greatest teacher.”

So much to learn and so little time. Dean Nicolai, an Indigenous archeologist attending the events at Yellowstone, tells me about an obsidian mine in the park that yielded trade routes for volcanic glass. Shards of this prized material could be flaked into exquisitely sharp edges. From Yellowstone, it was traded on a route that extended to the West Coast and eastward to Maine— 1,000 years ago.

“The mine is 35 feet deep,” Nicolai said. The mine is one of nearly 2,000 documented archeological sites in the park. His colleague Tim Ryan points out plants and medicine at Storm Point on the edge of the vast Yellowstone Lake. He shows us wild-growing elk thistle with a crunchy celery-like heart, yarrow that was used as a wound antibiotic, and wild carrot. Colored lupine seeds served as decoration before beads came through from Europeans. The bulrush was used as tipi covers and for burials.

“Grizzly bears showed us what foods to eat and what roots to gather,” said Ryan, who is also Indigenous. When he was a boy, Ryan liked to spend time outdoors alone. His grandmother noticed this and told him to stay aware because the plants and animals might start talking to him. Today, he is a STEM instructor at Salish Kootenai College, balancing his Indigenous traditional knowledge with a scientific background in plant ecology.

We hear stories of dislocations, massacres, and other tragedies associated with the genocidal policies of settler colonialism as it moved west. But we hear many more tales of the resiliency of tribes, the spiritual practices and ceremonies of interrelatedness at the heart of these cultures. The secret medicine, if there is only one, is surely gratitude.

Throughout the week of events at Yellowstone Revealed, bus tours led by particular tribal nation representatives take visitors to locations of significance within the park, tell stories, share knowledge, and embed the experience in perspective unique to that culture. We get on the Blackfeet bus and learn about the Iniskim, or buffalo stone, a naturally formed talisman derived from 65-million-year-old ammonite fossils found in the region. If you have one, you will never go hungry. Blackfeet tipi designs carry the Creation Story and cosmology of the people: the story of Star Boy, a union between the celestial and terrestrial planes of existence.

Yellowstone was where the people cached their tipis for the following summer, caught eagles for their feathers, carved bowls from soapstone, and gathered bitterroot and Saskatoon berries for their mild narcotic effect. There were 300 uses for the many parts of the buffalo, Blackfeet elders tell me, which is being brought back from the brink with help from 30 tribes in the region.

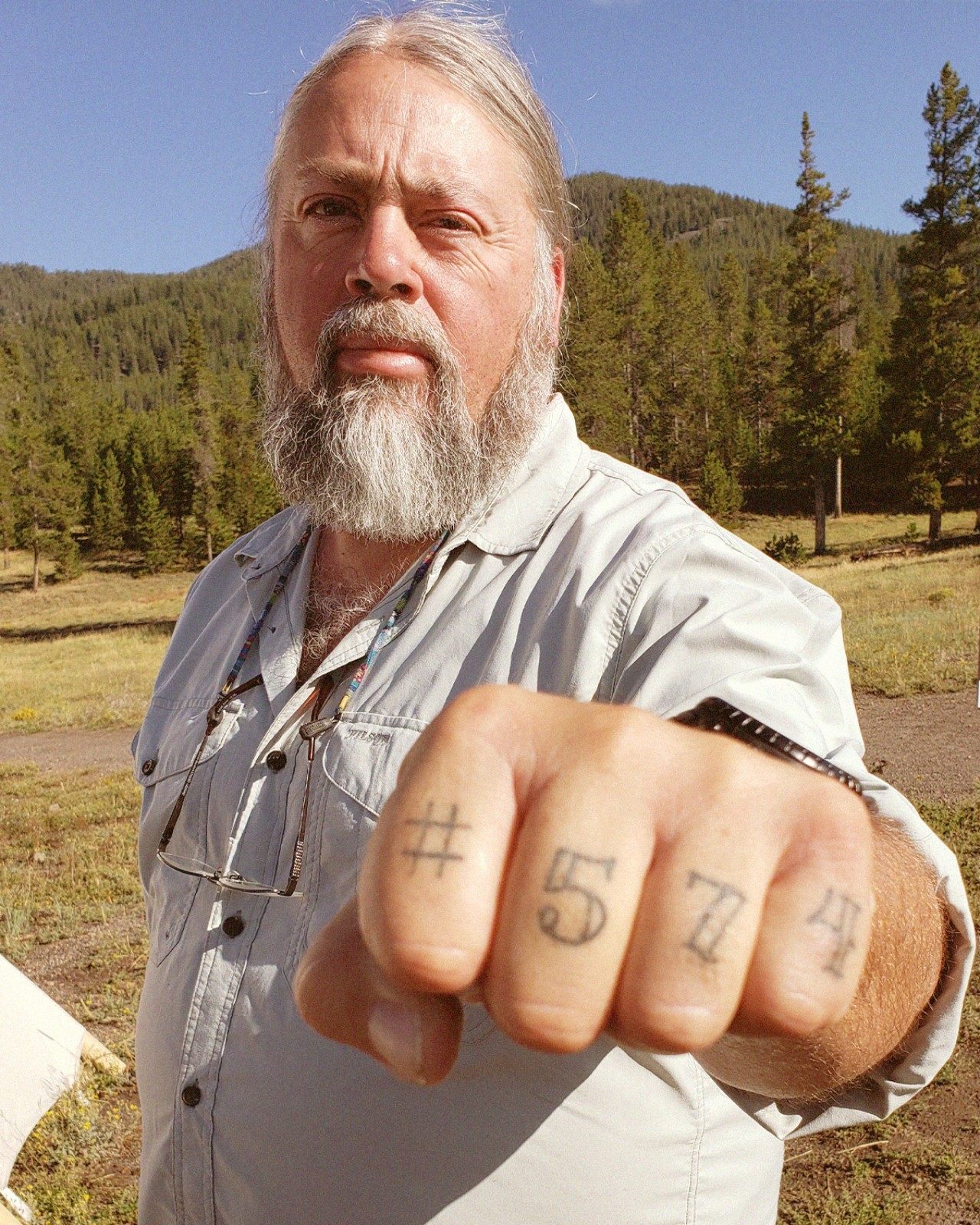

At every step of this journey, I get the feeling we are skimming the surface of cultures with profoundly complex and deeply held beliefs that tie to the land in specific ways. Multiply this shard of the mosaic by 574, and you will get a sense of the multiplicity and multi-dimensionality of Native America. That’s the current number of federally recognized tribes in the U.S. Hundreds more exist here—and north and south of the border.

Chris La Tray, a representative from the Little Shell Chippewa of Montana, proudly displays a tattoo showing that his tribe is the latest to acquire this recognition: “#574” is inked on the fingers of his closed fist. But La Tray knows that the reality of tribal consciousness always goes deeper than government recognition. It’s about family, memory, and cultural survival and adaptation.

Stories are culture, and perhaps Indian elders are revered in special ways as they are the containers of knowledge passed down orally from time immemorial. As our bus ride reaches an overlook of the river and field of Hayden Valley, our group piles out to see hundreds of buffalo doing what buffalo do: grouping, grazing, and digging around in wallows. I wonder for a moment if the buffalo babies will ever know they are in a protected park, the world around them changed inexorably, with some people holding the line against eradication and fighting for land back.

Blackfeet sisters Lailani Upham Bear-Chief and Carrie Lynn Bear-Chief share a song from their late elder Chief Earl Old Person, who also went by the names Stu Sapoo, “Cold Wind” in the Blackfeet language, and Ahka Pa Ka Pee, which translates to “Charging Home.” With a cell phone recording amplified on a small speaker, Old Person’s song resonates out across the field for whoever is still listening.

Correction,

September 9, 2022 3:57 pm

ET

The article has been updated to correct the spelling of Carrie Lynn Bear-Chief's name, which was previously spelled as Carey. We also updated the title of Earl Old Person to Chief Earl Old Person.

Yellowstone Reveals Its Indigenous Soul