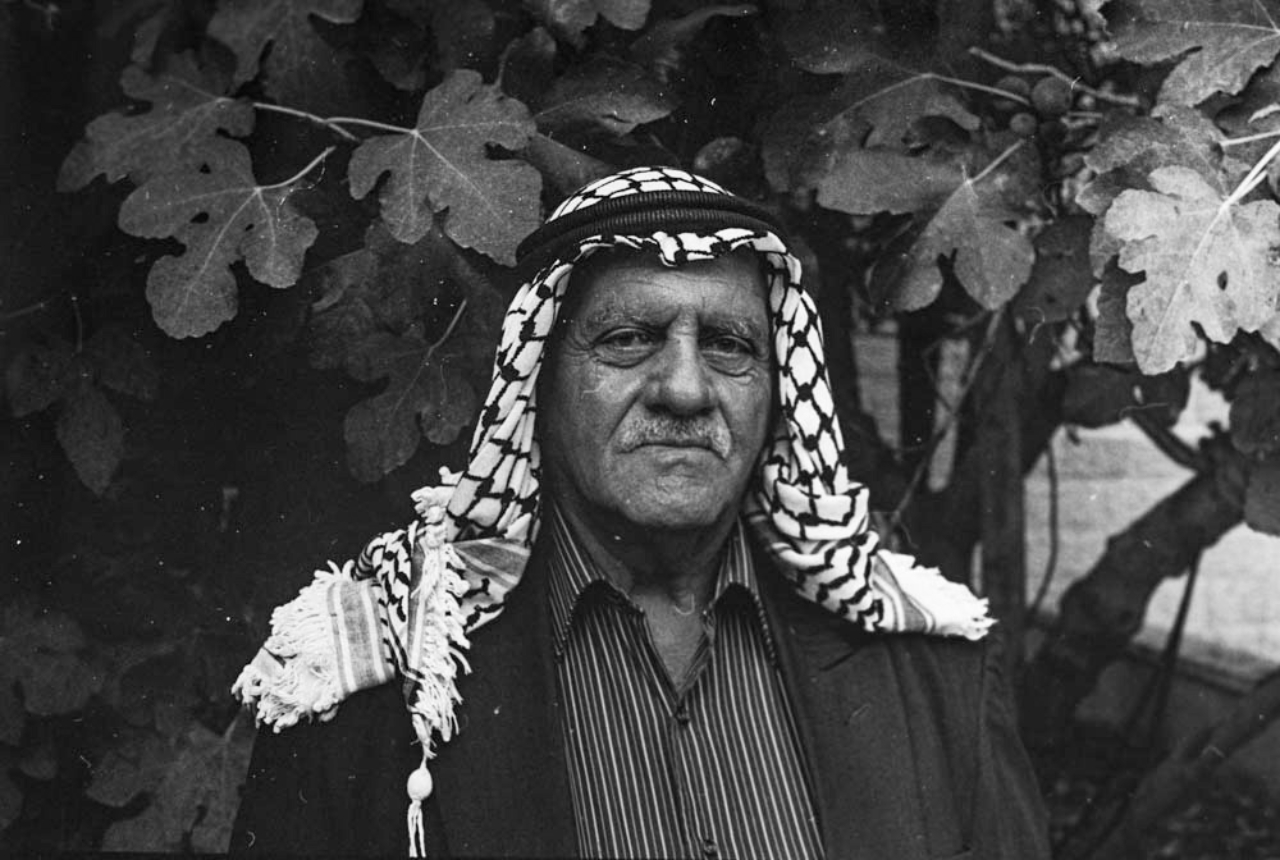

Photograph by Abed Zagout

Words by Sarra Alayyan

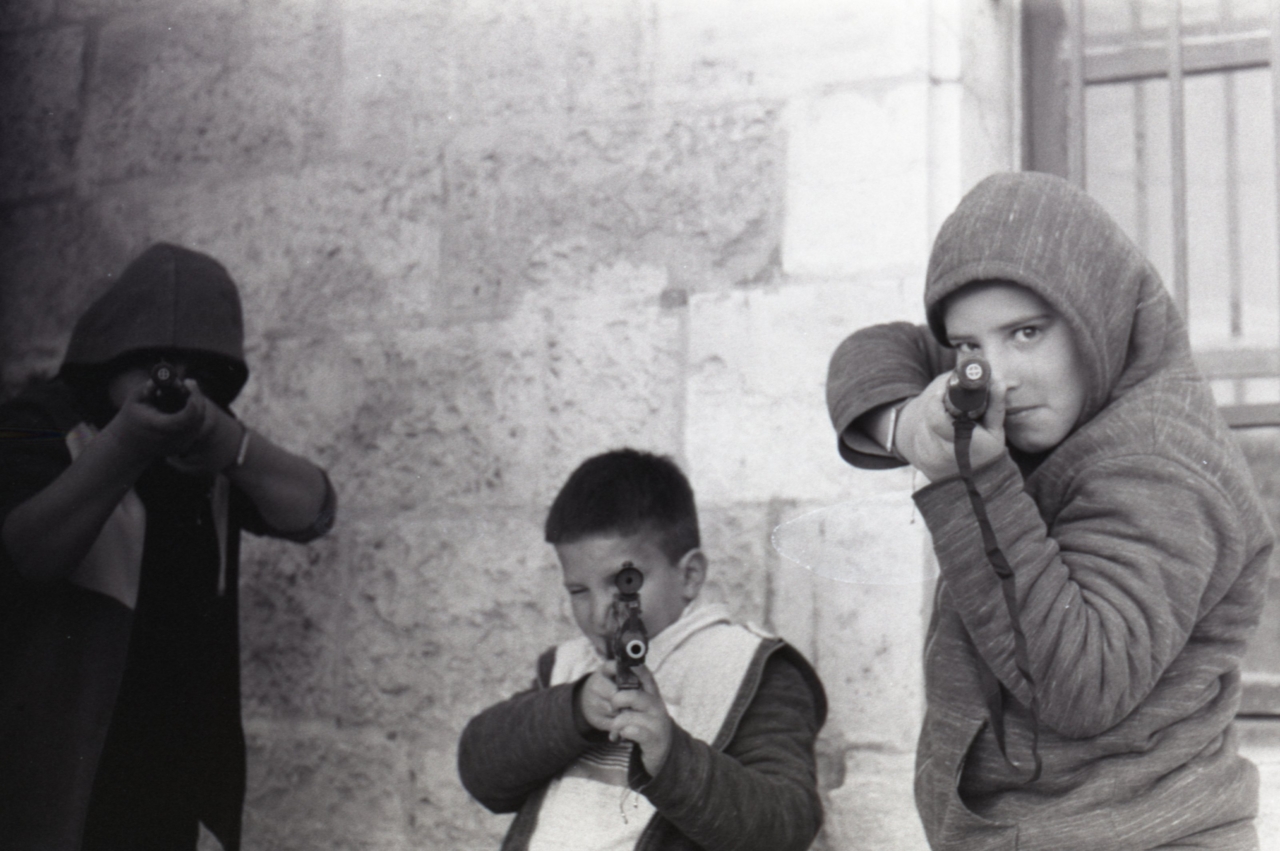

photographs by Ali Asfour and Abed Zagout

“Vision is always a question of the power to see—and perhaps of the violence implicit in our visualising practices. With whose blood were my eyes crafted?”

—Donna Haraway, Situated Knowledges

It may not be news that the control of representation can be a powerful tool of political, economic, and colonial domination. But it’s these tactics of erasure, denial, and obstructions of sight and narrative that are now in full throttle as Israel attempts to thwart accountability for its genocide and ethnic cleansing of Palestinians in Gaza.

In 1948, the creation of Israel began with the erasure of Indigenous Palestinians from view by disseminating images and stories of a “land without a people” for a “people without a land.” Since then, to sustain itself, Israel has relied heavily on the ability to control the representation of its settler-colonial aims and conditions, mainly by obfuscating or erasing the Palestinian figure in public imaginaries.

Today, soon to pass the nine-month mark since October 7th, Israel has killed over 37,000 people— more than 14,000 of which are children, and rendered the majority of the land unlivable, displacing 85% of Gaza’s 2.3 million people.

To build an image of legitimacy, Israel depends greatly on the production and circulation of Palestine through frames of violence, self-destruction, and barbarism. It achieves this in concert with the majority of Western media institutions. Each plays their role in manufacturing consent for genocide by parroting disinformation and propaganda by, for instance, casting widespread doubt on Gaza’s civilian death tolls (such as in a recently condemned The Atlantic article by Graeme Wood that went on to discuss the possibility of killing children legally).

There’s also been reporting on Israel’s efforts to censor and limit on-the-ground coverage of the genocide. Two weeks ago, they seized broadcasting equipment from the Associated Press, accusing them of violating a new media law by sharing footage with Al Jazeera. The law, passed in April, allows the government to ban international news outlets, particularly Al Jazeera, which it deems “harmful” to national security; Al Jazeera has called the decision a “criminal act.” The law follows a near-total ban on international journalists entering Gaza since October 7th.

“Foreign journalists have been banned from entering Gaza,” Ruwaida Amer, a Palestinian photojournalist based in Gaza, tells Atmos. “There is no foreign press in Gaza. The people in Gaza are the ones who are transmitting the events. Many of them are transmitting pictures because they want to tell the world what is happening in this big prison that the occupation created. Influencers on social media, amateur photographers, and journalists who risk their lives to convey the truth.”

Despite Israel’s strategies of concealment, it’s the work of Palestinians in Gaza, and them alone, that reveals the incomprehensible destruction of land, lives, and livelihoods. It’s figures like Motaz Aziza, Bisan Owda, Hind Khoudary, Wael Al-Dahdouh, and many others that have been tirelessly reporting from the ground despite the large-scale targeting of media workers. Over the last nine months, an estimated 108 journalists have been killed in Gaza, making it the deadliest period for journalists since the Committee to Protect Journalists began collecting data in 1992.

Palestinian death is often positioned as inevitable, and their lives as sentences of suffering with little context as to why.

For Abed Zagout, a photographer from Gaza who spent five months documenting the genocide before fleeing to Egypt to protect his family after many colleagues and their families were brutally attacked, documenting images and stories wields indelible power.

“Photography—and images in general—are considered the memory of nations. They capture conflicts, events, and crimes against the Palestinian people,” Zagout tells Atmos. “It is crucial that Palestinians themselves document and narrate these crimes through images, as images are undeniable pieces of evidence. The importance of these images is evident in their use as evidence in the International Criminal Court.”

Just last week, an AI image went viral following an Israeli airstrike which hit a displacement camp in Tal as-Sultan, a designated “safe zone” north of Rafah city, murdering at least 45 Palestinians. The attack came two days after the ICJ ordered Israel to halt its offensive on Rafah. The image showed a landscape with symmetrical tents arranged to spell out “All Eyes on Rafah,” set against a backdrop of snow-capped mountains; it was a scene meant to represent a rendering of a displacement camp. It was shared over 50 million times and drew widespread criticism for aestheticizing and sanitizing the genocide and mass displacement.

“I am against images produced by artificial intelligence of genocide scenes because there are indeed real photographs that we have captured depicting reality without artificial intelligence,” Zagout says. It’s a sentiment that’s echoed by other photojournalists. “The [AI] image captures a post-present reality,” says Palestinian Amman-based photographer Ali Asfour, adding that generative AI produces images based on aggregates of existing images. “It imagines our current moment as an inevitable tragic past, absolving us from engaging with the present and seeking change.”

AI favours familiarity, reproducing images we’ve seen before; in this case, it creates a conventionalized frame of war and displacement—putting aesthetic snowy mountains in a place with neither snow nor rolling alp-like peaks. The danger lies in its placating effect, in the distance it creates, and the opportunity it offers to retract our eyes onto scenes easier to swallow, ones that bear little resemblance to the horrific massacres live-streamed for us all to witness.

“Instead of confronting actual images of current suffering, it encourages us to look at a future where the tragedy has already occurred,” Asfour says. “Just post this on Instagram, then head to bed feeling accomplished, as if you’ve raised awareness. [It’s not enough to be] a witness; we need to start thinking of ways to take action.”

“It is crucial that Palestinians themselves document and narrate these crimes through images, as images are undeniable pieces of evidence.”

That said, there’s something altogether eerily dystopian about engaging in this discourse over an AI image, pontificating the do’s and don’ts of social activism, while real people are undergoing mass systemic slaughter. “There is a family called Al-Hasayna and Abu Sharia; more than 90 people from this family were killed, and they are still losing a number of their [family] members,” says Amer. “What is that called? When a place is bombed, and dozens are killed at once—that is called genocide. The pictures coming out of Gaza are real.”

All of the photographers who spoke with Atmos agree that one of the duties of witnessing and acting is remaining focused and undeterred. Debates around AI images and social media activism risk becoming distractions that direct sight away from what’s happening on the ground and the material conditions that allow Zionism to permeate public opinion in the first place.

If Palestinians feel they have a duty to document the horrors of their genocide and their daily lives under apartheid and occupation in order to assert their existence and humanity—showing their face to a world rendering them faceless—then we who purport to stand with Palestine, must witness the images and footage. To listen to their stories as they share them and as they speak them.

It is not just our duty to consume the footage, but to remain at all times cognizant that Palestinians are more than, in Asfour’s words, “faceless victims with a faceless oppressor.” All too often, Western media present an uneven and reductive view of mortality: Palestinian death is often positioned as inevitable, and their lives as sentences of suffering with little context as to why.

This was excruciatingly clear to those following the news over the weekend. On Saturday, four Israelis taken hostage on October 7th were released through a brutal operation that massacred more than 270 Palestinians and wounded at least 700. Plastered across many mainstream news outlets were Israelis rejoicing and smiling images of IDF soldiers with the hostages and their families. There were few images of Palestinians; only some showed photographs of Nuseirat’s rubble, sanitizing the corpses and bloodshed in favor of Israeli images of joy. Many headlines did not even mention the Palestinian loss of life. And those that did prefaced the numbers with “Hamas reports” or “Gazans officials say,” framing the dead as a mere turn of phrase—not whole worlds whose losses should move us to meaningful action.

Gaza is not simply a necropolis created by a universal condition of ethical and political decay, a theater live streaming global coloniality and moral bankruptcy in their most obscene forms. Gaza is a place where, despite collective humanity’s betrayal, the praxis of teaching life, humanity, steadfastness, and love abounds when it seems the rest of the world has forgotten their meanings.

To be aligned with Gaza and Palestine in its entirety is to be committed to Palestinian life in every sense of the word and to every material condition required to allow it to flourish freely—from supporting Palestinians’ right to armed resistance and struggle to the dismantling of Zionism. Witnessing as a means of frank solidarity should be done consistently with this endpoint in sight in order to, as Ali reminds us, “take action, not just for the present moment we are in, but for the future.”

Editor’s Note: Abed Zagout’s answers were translated from Arabic by Mahmoud Al Abed. Zagout is currently raising money via GoFundMe to go towards rebuilding his life in Egypt.

Depicting Palestine: What It Means to Witness a Genocide