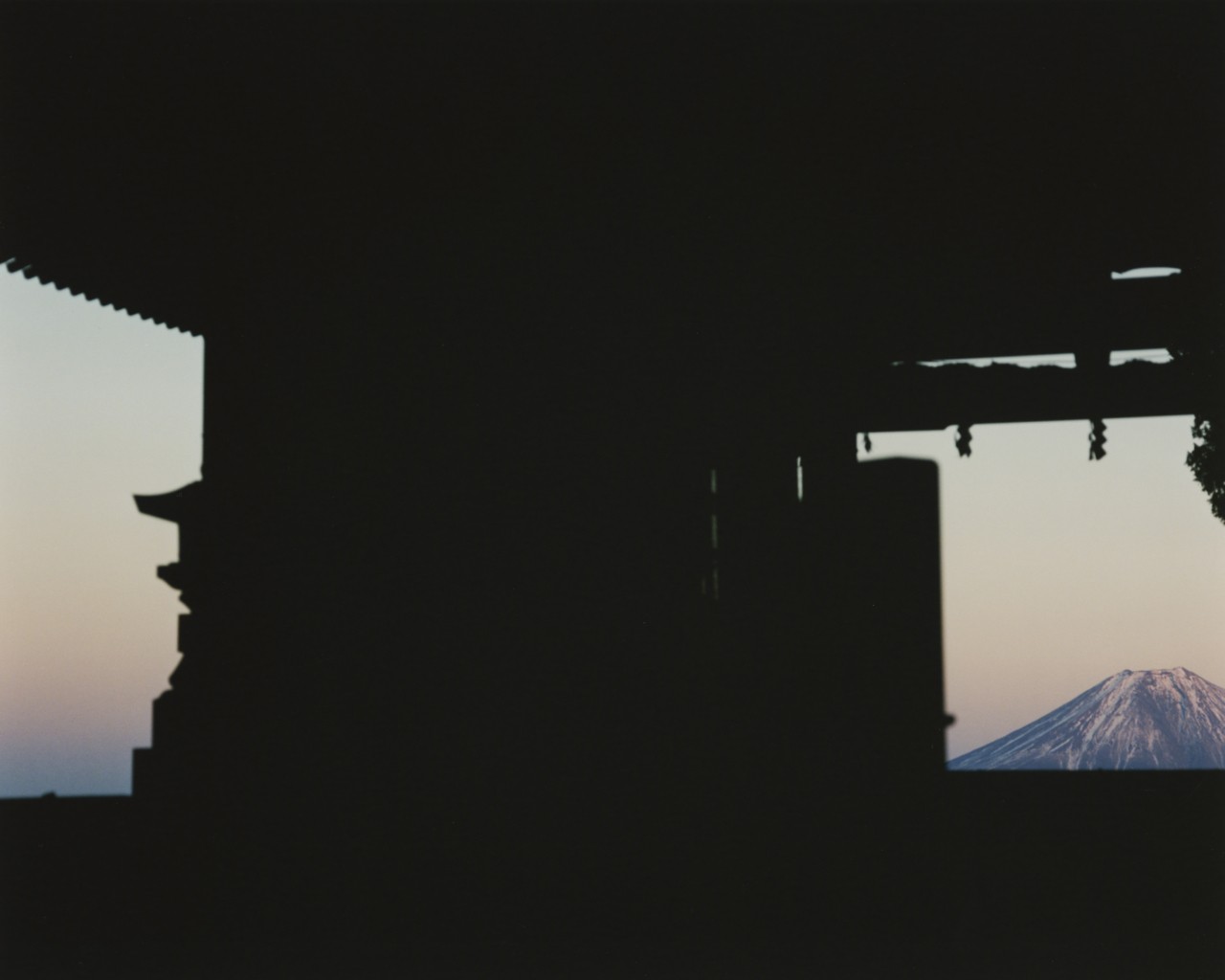

In this series, Stefan Dotter captures the sacred Shinto shrines of Japan and their surrounding winter landscapes, including snow capped mountains, frozen lakes and forests, and rare glimpses of wildlife.

Words by Mary Evelyn Tucker

Photographs by Stefan Dotter

“At its core, even our spirituality is Earth derived. The human and the Earth are totally implicated, each in the other…If there is no spirituality in the Earth, then there is no spirituality in ourselves.”

—Thomas Berry, “The Spirituality of the Earth”

We are at a moment of enormous crisis in which every major institution—political, economic, educational, and religious—seems to be unraveling before our eyes. This moment is being described as a polycrisis of social and environmental challenges, including wars that drag us further into dead ends of militarism and empire. We are looking for ways through a morass of problems that seems insurmountable. We feel in the dark because we have lost our way, our connections, our grounding. Ecoanxiety engulfs us; climate grief enwraps us. All we want to do is turn off the barrage of awful news.

Can this deluge of darkness crack open into light? Spiritual ecology may lift us back into alignment with life, living systems, and the healing power of relationality.

If we are to end the era of hyperindividualism, we will need new ways to reform, reshape, and reinvent community. Spiritual ecology is part of this re-creation of being and belonging in a world that is unraveling. It involves processes of recognizing our embodiment in matter through the process of evolution across deep time, our resonance with kin across species, and our reweaving of awe into our mind-body being. Does this upset or reset our sense of place and purpose? Let’s hope so. Otherwise, we risk the steady slump into meaninglessness and ennui.

We can become untethered in the endless cycle of consumption that feeds on our souls until they are devoured by emptiness. Can we step away from this cycle? Can we stop being lured in by the sparkle of the new, the cool, the yet-undiscovered toy?

Spiritual ecology and religious naturalism may untangle us from consumer materialism and reweave us into the creative matter of vibrant evolutionary processes. They may reignite a relational resonance with our kin, both human and more-than-human. They may reawaken a primal awe in the face of complex, living systems infused with sentience.

For we live in a dynamic, unfolding universe that has birthed, over the course of 10 billion years, stars and galaxies filled with planets circled by moons. Four billion years ago, on one of those planets—our own Earth—atoms became cells and then multicellular life amid oceans and river systems. And nearly 14 million years later, primates emerged on the African savanna and eventually evolved into homo sapiens. Keeping deep time in mind gives us a fresh context for linking cosmic spiritualities and spiritual ecologies, from the explosion of stars to the rise of carbon-based life. Experiencing the universe, Earth, and humans as one entangled continuity of being lifts us out of our endless dualism of humans as separate from nature.

This evolutionary context places us in vast circles of relationality where we feel cosmic resonances with the sun, moon, and planets of our solar system, along with a sense of belonging to the biodiverse ecosystems of our planet. This belonging includes “all our relations”—family and friends, forests and fish. Such reciprocities awaken us to the cycles of nature, which show us how we are embedded in life systems of birth, death, and rebirth that surround, embrace, and sustain us. Reverence and respect are the virtues that nurture these rites.

Such spiritualities have been widespread in earlier societies—Indigenous, Buddhist, Daoist, Confucian, and Hindu—and are arising anew in our times. Just as we are on the verge of sinking into exhaustion and numbness, something fresh is cracking open the closed doors of our minds and hearts.

“How do we create beauty that has ethics embedded within it?”

These renewed cosmic spiritualities and spiritual ecologies are bringing us in touch once again with wonder and delight, prompting us to move beyond the many addictions that surround us, to realize that we live in a world of endless complexity. This complexity is awash with different kinds of sentience: Tree roots in the forests are communicating; chimps and bonobos display distinctive cultures; birds, salmon, and caribou migrate across great distances. These innate intelligences are not yet fully understood, but they provoke wonder and amazement.

So we hold to the promise of new and ancient sensibilities arising—embedded in deep evolutionary time, in relational resonances, and in awe and surprise. Will these aspects of cosmological and ecological spiritualities be sufficient to sustain us in these chaotic times? The yearning is clear, the hunger is great, a transformation is still possible. But it will require a massive infusion of spiritual energy to break through. We are dwelling in a living Earth community, embracing kin with a reciprocal and radical love. Such resonances can reignite wonder—creating a fire of transformation that might renew the face of the Earth.

Here we have convened three scholars to discuss the promise of spiritual ecology—Vijaya Nagarajan of the University of San Francisco, who studies Hinduism and women; Dan Smyer Yu of Yunnan University, who focuses on Chinese and Tibetan religions; Carol Wayne White of Bucknell University, who focuses on religious naturalism—with myself, representing the Yale Forum on Religion and Ecology, as a facilitator.

Mary Evelyn Tucker

We’re talking about spiritual ecology, which is growing in interest, vibrancy, and relevance. We’re going to start by asking: What is spiritual ecology, and what is religious naturalism?

Carol Wayne White

Religious naturalism is an emergent worldview based in an understanding of reality informed by scientific studies, religious values, and philosophical ideas. It promotes a view in which nature is the ultimate reality. In doing so, religious naturalism dethrones humans from thinking we’re at the center of reality, and it has intrinsic ecological, social, and theoretical implications for how we think, feel, and act.

Vijaya Nagarajan

For me, religion and ecology are related to spirituality and ecology. Religion we tend to think of as a kind of box that has edges and is constrained in terms of definitions and practices; whereas spirituality and ecology are much more like an open box, where the many different tools that we find in religious traditions all over the world can be put together. It’s like the windows are open in the spirituality and ecology buildings—the doors are open, the wind is allowed to come in, you can hear the bird calls, and you can see snakes in the grass. The entire kinship of life is visible in that worldview.

Part of my research recently has been on Hinduism and climate. I’m trying to think about 5,000 years of Hinduism and imagine it as a spiritual tradition that has tools we can use to understand ourselves in relation to the larger kinship of the world.

Dan Smyer Yu

I grew up in China and my ancestors are Rema, which is a very small ethnic group in western China, the eastern Tibetan plateau, in the ecological border zone. This is the basis of my interest in religion, ecology, and spiritual ecology.

Besides being a scholar, I’m also a regenerative subsistence farmer. Four years ago, when the pandemic started and I started working from home, I realized there’s something else I need to do besides academic writing. I think the soil matters, the trees matter. So my wife and I decided to have a piece of a small farmland, about five acres, and we started to do our work. It’s slow progress, but we are planting seeds of change and hope something fruitful will come.

Spiritual ecology can be synonymous to what Mary Evelyn calls religious ecology, or what the UN refers to as faith-based ecology, or in general could be interfaith ecotheology. The theology could be any religion.

Monotheistic religions tend to treat divinity as otherworldly. I’m leaning toward looking at the spiritual state of Earth as a series of constant, animistic fluxes as a part of a pan-human Indigenous knowledge of life on Earth. Animistic means the intangible essence of life embodies itself in myriad physical forms.

MET

How is this relevant for our present circumstances?

CWW

As a religious naturalist, I define spirituality as a mode of reflecting, experiencing, and envisioning one’s relationality with all that is.

Spirituality is a vital awareness that pervades being alive. Because humans are natural organisms, we are part of this biotic community. And the ecological implication is that, when we have this embodied awareness that we’re material, relational beings, then we have some important actions to take. Ecology and spirituality have never divorced from each other because even human bodies are ecosystems. Everything can be part of this living entity that we call Earth.

VN

We need to restore, reinvent, and reimagine languages of wholeness because we have, in the last 500 to 700 years, split ourselves from the natural world. Our language splits us from the natural world and keeps those artificial barriers up.

So part of my work has been trying to see: How does one convey the concept of the commons? It’s part of that vocabulary of spiritual ecology. Every religious and spiritual tradition around the world has these ways of tying the very small and the very big together. How do we bring those vocabularies back into the present so that we can see how the highways connect with trees or the air?

I’ve also been very preoccupied with understanding waste, because our incapacity to see waste has led to multiple problems. As Amitav Ghosh said once, “The problem of climate is the problem of waste.”

MET

Ghosh ends his book The Great Derangement with this call for a spiritual ecology, even citing Pope Francis’s encyclical Laudato si’.

DSY

In terms of the relevance of a spiritual ecology, let me start with the UN’s [idea of] sustainable development. To me, it’s kind of a failed idea. It was proposed in 1987. But when we look at the environmental track record of the entire planet, we have more crises than ever. It’s time for a spiritual ecology, because sustainable development is a very science-based idea about the so-called carrying capacity of the Earth in the material sense.

Spiritual ecology tells us a different story of the Earth, and allows us to recognize that our reverence for the sentience and sacredness of the Earth is the basis for the mutual flourishing of humans and nonhumans. I want to see sustainable happiness, not sustainable development. Because whatever we extracted from the earth, [it was because] we wanted to make ourselves happy.

In terms of how we might shape spiritual ecology, I think we can start with our spiritual relations with the Earth. The purpose is to correlate the environment and ethics with local, traditional ways of sustainable living. That allows us spiritual ecologists to translate whatever is stored in religious texts, traditions, and customs into publicly accessible environmental language.

CWW

One thing that spiritual ecology does is introduce a type of language that has often been marginalized by contemporary scientific approaches to the Anthropocene. Religious voices, perspectives, and methodologies are often overshadowed by the scientific. It’s not either/or; it’s about adding more voices to the conversation.

Rachel Carson writes, “I believe that the more clearly we can focus our attention on the wonders and realities of the universe about us, the less taste we shall have for destruction.”

There’s this fascinating reciprocity, and it avoids a managerial model of environmentalism that thinks that we’re separate from the thing we’re trying to save. Religious naturalism rejects that “we are trying to do something for you” attitude. The very thing we’re talking about, we’re a part of.

“I want to see sustainable happiness, not sustainable development. Because whatever we extracted from the Earth, it was because we wanted to make ourselves happy.”

MET

I have lived within a very scientistic environment for a long time at Yale School of the Environment. And I just want to interject briefly that [the ideas of] animal consciousness and the livingness of trees and plants are coming from scientists too, now. This is an exciting moment.

CWW

In the field of botany, Robin Wall Kimmerer and a number of others have provided wonderful language for forms of knowledge that have been diminished with this march towards scientism.

VN

Last year I was invited to teach ethics in the engineering program at the University of San Francisco. I left engineering school because it didn’t have ethics. I fought with my deans at the time, saying, “We have to have ecology and ethics and equity in the designing of the engineering systems themselves.” They laughed at me. So 45 years later, to have a chance to bring morality and ethics from several religious traditions into the training of first-semester engineering students was just thrilling.

And the book that made the most difference was Robin Wall Kimmerer’s book. The levels of awareness that her writing helped my engineering students achieve was breathtaking.

The idea of the gift is so central to the idea of the commons, and the idea of waste. It’s like Gandhi said more than 100 years ago: If India starts behaving like Britain, it’ll be the whole Earth that is stripped. And that’s what’s happened. The whole world has become the colonizing empire. We are stripping the world like locusts. How do we jump out of that path?

Part of that requires us to see the gifts that make us and that we make in the world. It’s hard for people to understand because they think of commodified gift-giving. You have to unpack what “gift” actually means from a non-commodified perspective to be able to even perceive the gifts around us.

DSY

The United Nations Environment Programme’s Faith for Earth Coalition statistics say that 80% of the world’s population is religious. What does it mean that these religious constituencies hold ecological knowledge, written or oral?

I have been working on a theory that I call the affective consciousness of the Earth. The biosphere is the most culturally vibrant sphere of the Earth. Cultural diversity and biodiversity are in direct [proportion]. When one side decreases, the other side decreases. By connecting the physical Earth with the spiritual Earth, or the animistic Earth, we are able to see that the Earth has a life of her own that interweaves everything and everyone together.

This interior force of the Earth is incarnated in different exterior bodies on the Earth’s surface. Humans are interconnected with the interior force of the Earth through the language of spirituality and religious practices.

CWW

Alfred North Whitehead is another major thinker who, during the 1930s, brought forth an ecological understanding of reality. The basic metaphor that Whitehead used was that reality is basically about change.

Rachel Carson also wrote, “There’s nothing static about an ecosystem, something is always happening, energy and materials are being received, transformed, given off. The living maintains itself in a dynamic rather than static balance.” There’s no stasis in the universe at all. Even in what we call nonorganic entities, there’s always something happening—think of electrons that are jumping orbits. When we begin to understand these beautiful elements of scientific and philosophical study, they amplify our ecological understanding.

MET

I’ve had discussions with scientists, like Ursula Goodenough, who would say the difference between the animate and the so-called “inanimate” world is a strict line. But even the rocks are changing—erosion, plate tectonics, and so on.

VN

In my book Feeding a Thousand Souls: Women, Ritual, and Ecology in India, I was working on this incredible mandala tradition all over India—400 million Hindu women do this some time during the year, where they make designs on the household threshold with rice flour. Hundreds of women told me, “We do this every morning as our first ritual act of the day, before sunrise, to honor the Earth goddess and to ask for forgiveness for all the actions that we are about to do that could harm her and all the actions that we have done in the past that have harmed her.”

Ethics becomes woven in very closely, like a piece of knitting, with aesthetics. How do we create beauty that has ethics embedded within it? I call it embedded ecologies. We are swimming in a sea of unraveled threads that have been undone by language, by actions, by rituals of modernity. We need to recall, through ritual action that we do on a daily basis, that we want to go towards the flourishing of life.

“We’re called to participate in life as a species, and we have a role to play.”

CWW

This aesthetic-ethics phrase—I use the word wonder. Wonder has the capacity to mitigate against nihilism and indifference and knit the alienated forms of relationality together.

I want to finish with a line from Robin Kimmerer. She says, “Even a wounded world is feeding us. Even a wounded world holds us, giving us moments of wonder and joy. I choose joy over despair. Not because I have my head in the sand, but because joy is what the earth gives me daily and I must return the gift.” That’s the type of ethics I think that can be generated from this spirituality.

DSY

To me, it’s also about Earth speaking through us.

CWW

We’re called to participate in life as a species, and we have a role to play. It’s the grandeur of life itself that inspires and motivates us. Whatever vocabulary we’re using, we’re really talking about how beautiful, gorgeous, and fascinating life is—and we’re a small part of it. If we can give back what has been given to us, we’ll be seeing a different world.

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

This article first appeared in Atmos Volume 9: Kinship with the headline “The Soul of the World.”

Why the World Needs Spiritual Ecology