WORDS BY HUMBERTO BASILIO

photographs by Sarah Karlan

In the shadow of Pueblo, Colorado’s towering smokestacks, the state’s last coal giant is nearing its end. By 2031, Comanche Unit 3, once promoted as a state-of-the-art power plant, will close decades ahead of schedule. Its history has been marked by controversy and years of polluted air.

For many residents, the plant’s legacy is measured in hospital visits and asthma inhalers. Pueblo has some of the highest rates of respiratory disease and cancer in the state, disproportionately affecting communities of color. “We have a history of environmental classism that has left a mark in our city,” said Sal Pace, a Pueblo resident and former county commissioner.

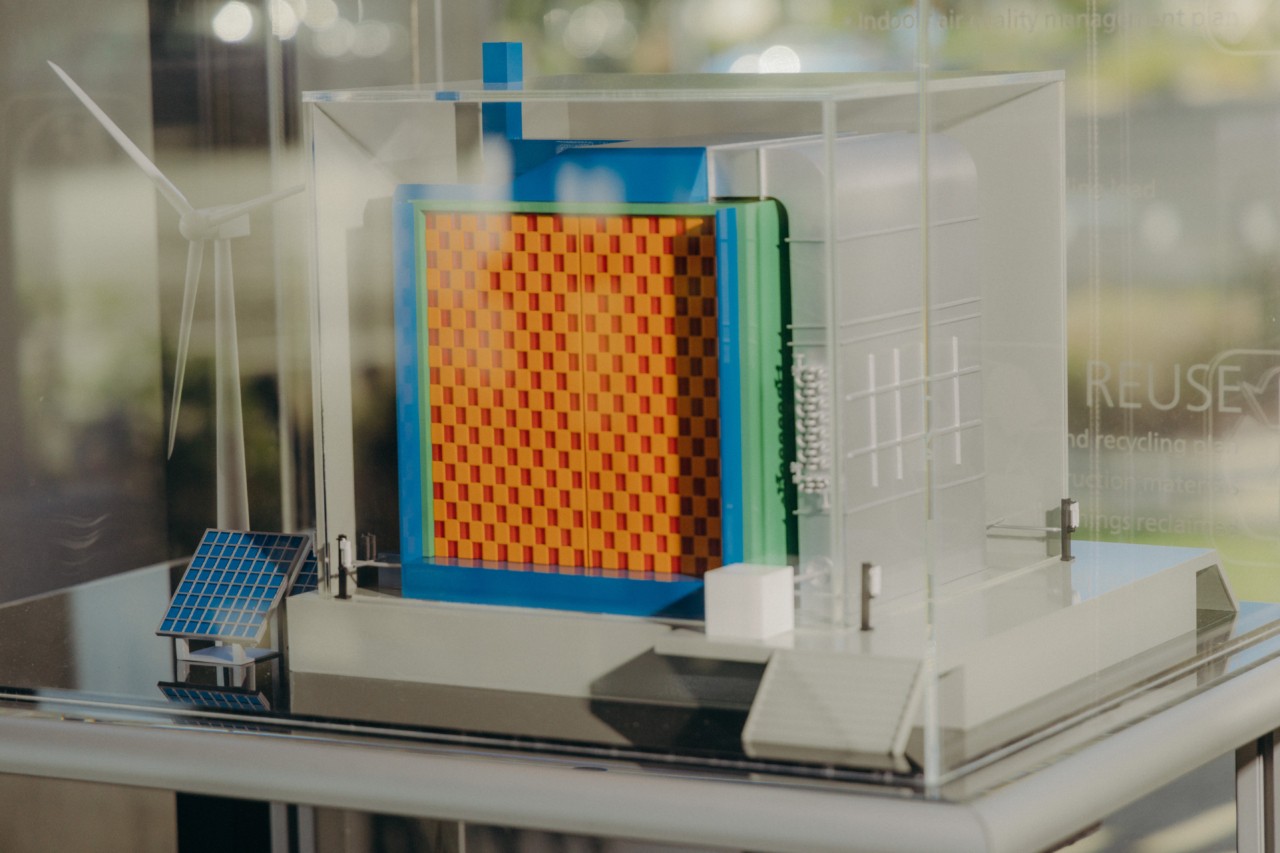

Now, a new proposal aims to rewrite that story. Instead of coal, Pueblo could soon host one of the largest clean energy hubs in the United States. The plan is to store wind and solar electricity as heat inside massive thermal batteries. These devices can take in 800 megawatts of power—about equal to Comanche Unit 3 operating at full tilt—and steadily release 200 megawatts of piping-hot air or steam to supply nearby factories with clean, round-the-clock energy. For comparison, the Denver district heat system can consume up to 250 megawatts of steam energy.

Pace believes the shift could change lives. “The transition away from coal to renewable energy would help Pueblo lower asthma rates, reduce emergency room visits, improve quality of life for people’s youth and elders,” he said. The project, he added, “gives us the chance to change course.”

Around the world, engineers and corporations are turning to thermal batteries as a practical solution to one of the most challenging yet overlooked problems in the climate crisis: the decarbonization of industrial heat. These bricks of stored energy may prove to be among the most effective solutions, cutting carbon dioxide emissions dramatically while pushing forward the global shift away from fossil fuels.

No part of the global economy burns more fossil fuels than the factories that produce almost everything we consume—from construction materials such as steel and cement, to the fabric for clothing, to the plastic that wraps our food. Manufacturing requires industrial heat to power and catalyze its processes, and industrial heat accounts for more than a quarter of all the fuel burned worldwide. Burning fuel is responsible for about 80% of global greenhouse gas emissions.

Faced with the global climate crisis, scientists and governments around the world are searching for cleaner ways to generate the heat that keeps industry running. Yet decarbonization and the shift to renewable energy require significant investments of time and money that most industries thus far have been unwilling to take on.

After founding and leading one of the companies at the forefront of designing and manufacturing solar steam generators, John O’Donnell realized that to convince heavy industry to transition to renewable energy, he first needed to offer them consistency. The key was finding a way to guarantee that power could be stored and would not depend on sunny days or strong winds.

“If you have solar energy and you want to use it for an industrial process, first thing you need to do is find a way to store it,” O’Donnell said. If he could design a tool capable of storing that electricity, he explained, “we could actually create these conditions where large flows of private capital would build profitable projects that would solve the problem.”

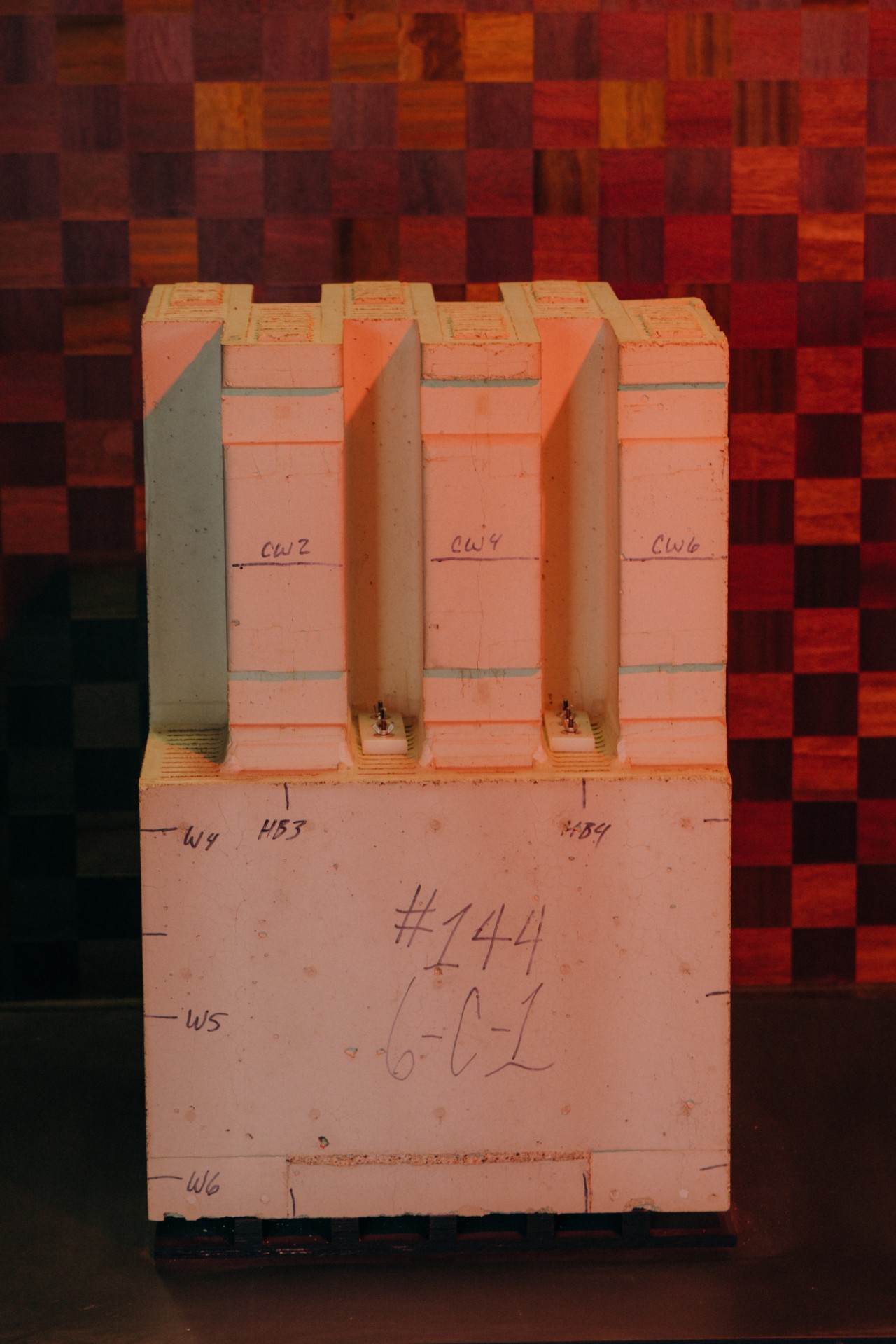

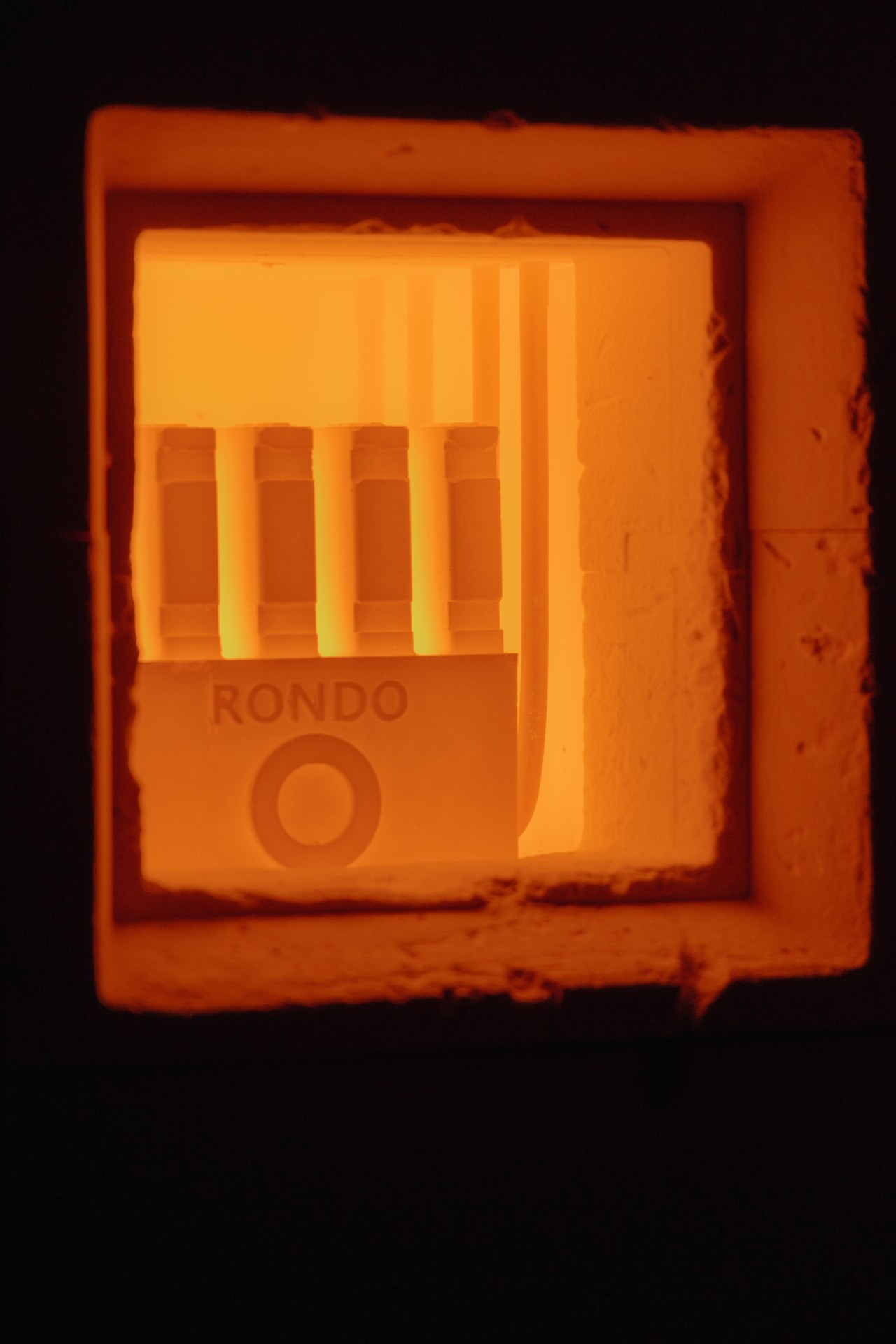

After 15 years of work and prototyping, O’Donnell created his firebrick: the cornerstone of his new company and the defining feature of Rondo Energy’s heat battery.

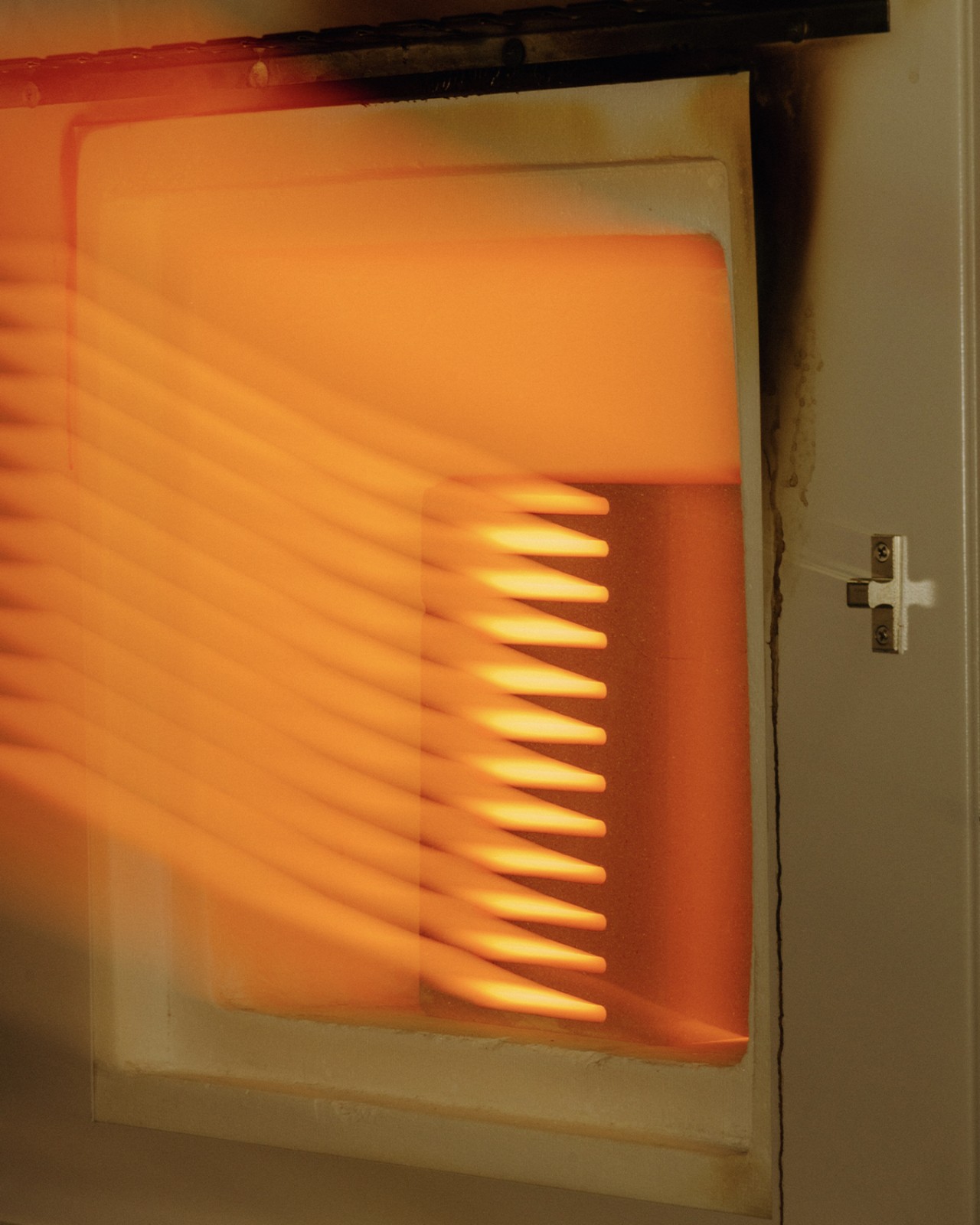

The battery looks simple; it is anything but. Composed of a stack of bricks placed inside a steel container about half the size of an NBA basketball court, it functions like a rechargeable furnace. Electricity from solar panels and wind turbines flows into the device and gets converted to heat, reaching searing temperatures in excess of 2,000 degrees Fahrenheit. The heat is locked away, ready to be released hours or days later. When a factory calls for power, air is pushed through the glowing bricks, emerging as a blast of heat or steam hot enough to forge steel or fire cement. AI systems fine-tune the process, delivering precise energy on demand. Designed to be modular and easy to install, these brick batteries can drop into existing facilities, O’Donnell said, replacing fossil-fuel boilers and supplying factories with round-the-clock clean heat.

O’Donnell sees his brick batteries as far less glamorous—even boring—compared to his days as a computer scientist working on nuclear fusion. But unlike nuclear fusion, which remains scientifically challenging for large-scale commercial power generation, Rondo’s heat battery can be built today with materials and technologies already on the market.

“We are not doing material science, but tapping into supply chains that already existed,” O’Donnell said. “So we’ve come to really deeply love boring bricks.”

Rondo has already secured $160 million in investment for its operations and is one of the leading companies producing heat batteries in the United States. Other companies have also begun designing and operating their own batteries, and at least five of them, including Rondo, are part of the Thermal Battery Alliance, an organization that seeks to accelerate the deployment of thermal battery solutions.

Analysts believe that electrified industrial heat could become the next trillion-dollar market. Falling production costs for wind and solar power are creating the conditions to scale heat batteries to a massive level, O’Donnell said.

In a 2023 report, the energy and climate policy think tank Energy Innovation estimated that heat batteries could make the cost of industrial heating with electricity competitive with natural gas, while replacing 75% of fossil fuel use in U.S. industrial energy demand. That reduction would equal the total energy use of all households across the 12 states with the highest consumption combined.

Another global study modeled a future where 100% of energy worldwide comes from wind, water, and solar power, with firebricks used to store industrial heat. Its simulations across 149 countries found that adding firebricks could slash the need for batteries by roughly 14% and cut hydrogen fuel by about 31%. Other energy demands, from underground heat storage to onshore wind, also decreased.

“After the rise of solar energy and lithium batteries, this is the third most exciting thing in my career that I have seen,” said Eric Gimon, a policy adviser with Energy Innovation who also coauthored the master plan proposal for Pueblo’s new solar park.

“There was always this idea that we were going to clean up electricity first, then transportation and buildings, and eventually we would get to industry because it was hard,” Gimon added. “But we do not have time for that, and there is a lot of benefit that can happen if we do these things in parallel.”

Yet, Gimons said that a lack of governmental support and industry willpower are major hurdles for the heat battery market.

Many industrial customers remain reluctant. “They do not want to take risks, especially if it is such a core element of their production, their process, their business,” said Doron Brenmiller, chief business officer of Brenmiller Energy.

Brenmiller, who is bringing his thermal batteries to the European market, has focused on making the product as attractive as possible for companies. His firm takes on nearly all the risk by financing, building, securing permits, arranging contracts, and delivering the service in a single package. Depending on the client’s needs, the construction of wind and solar farms can also be included. The customer’s role is reduced to signing a long-term agreement of seven to 20 years. “They are going to purchase steam by the cubic meter from us, and we are going to do all the rest,” he said.

The transition will not be easy, and it needs “smart policy” behind it, said Gimon. But cleaning up industrial heat also offers major opportunities for job creation and economic growth.

Programs already exist at the local, state, and federal levels to subsidize industrial development, and these could be tied directly to adopting clean heat technologies. The Department of Energy’s Industrial Efficiency and Decarbonization Office and the Inflation Reduction Act opened millions of dollars to modernize facilities, retrofit boilers, and install advanced heat systems. Tax credits and low-cost financing through federal green banks could further reduce the risk for companies willing to try thermal batteries at scale. Regulators could also create new electricity tariffs that reward facilities for drawing power from the grid when wind and solar are abundant and returning it when demand is highest. That shift, Gimon said, would not only make thermal batteries more competitive; it would also strengthen the grid and accelerate the clean energy transition.

Not every region has suitable weather to bank renewable energy. But in Pueblo—which boasts some of the strongest and most consistent sunshine in the country, plus large, flat, and affordable stretches of land near transmission lines—clean heat batteries are an appealing option. The shutdown of Comanche Unit 3 also frees up critical grid capacity, giving renewable projects a clearer path to connect without expensive upgrades.

The project is not yet certain, but Gimon believes local and state officials now have all the information they need to make an investment that could transform the lives of Pueblo’s 110,000 residents.

Replacing a coal plant with a renewable energy park would mark a decisive break with the past, Gimon said. The solar park is expected to create hundreds of jobs in construction and operations, while giving local businesses opportunities to supply materials and services. Over time, lower energy costs and cleaner air could make Pueblo more attractive to new industries and residents.

“It could really turn the page to a new chapter,” said former County Commissioner Pace. “My hope is that my children will grow up in a stronger, safer, cleaner Pueblo.”

This Brick Is the World’s Most Boring Climate Solution