Photograph by Dennis Eichmann / Connected Archives

Words by Bridget Reed Morawski

In the U.S., air conditioning often seems like a birthright. The technology is ubiquitous; walk into many grocery stores, libraries, fitness centers, airport terminals, doctor’s offices, barbershops, convenience stores, places of worship, schools, museums, shopping malls, bus depots, restaurants or bars in the warmer months and you’ll likely feel the chill of conditioned air—or immediately notice if the place doesn’t have working A/C.

But the country didn’t come with pre-installed air conditioning. Although there were earlier iterations, the birth of modern air conditioning didn’t happen until the summer of 1902, when a young engineer named Willis Carrier was tasked with solving the humidity problem ruining a Brooklyn publisher’s production schedule. Carrier created a number of mechanical drawings and made further improvements to his designs later that year, inspired by “a cold, foggy train platform in Pittsburgh,” according to the global HVAC firm he founded that still bears his name.

The technology was too expensive in the ensuing decades for most people to take advantage of it, but “by the late 1960s, most new homes had central air conditioning, and window air conditioners were more affordable than ever, fueling population growth in hot-weather states like Arizona and Florida,” according to the U.S. Department of Energy.

Sometimes a soft susurrance whispering from the other room, sometimes a dull roar with disconcerting bangs and clanks, air conditioning now adds an instrumental layer to the soundtrack of the average American summer. That now-common comfort makes life feel easier for those who have access to it, but every hum and thrum also challenges our ability to keep the country’s lights, gadgets, and appliances powered up—and our chances of decelerating climate change.

Every air conditioner needs electricity to function. But, the power sector providing that electricity is a major emitter of the greenhouse gasses that drive climate change. In fact, it accounts for roughly a third of total U.S. emissions. And while other domestic devices like light bulbs or refrigerators use plenty of power, air conditioning is the largest single demand source in a private residence.

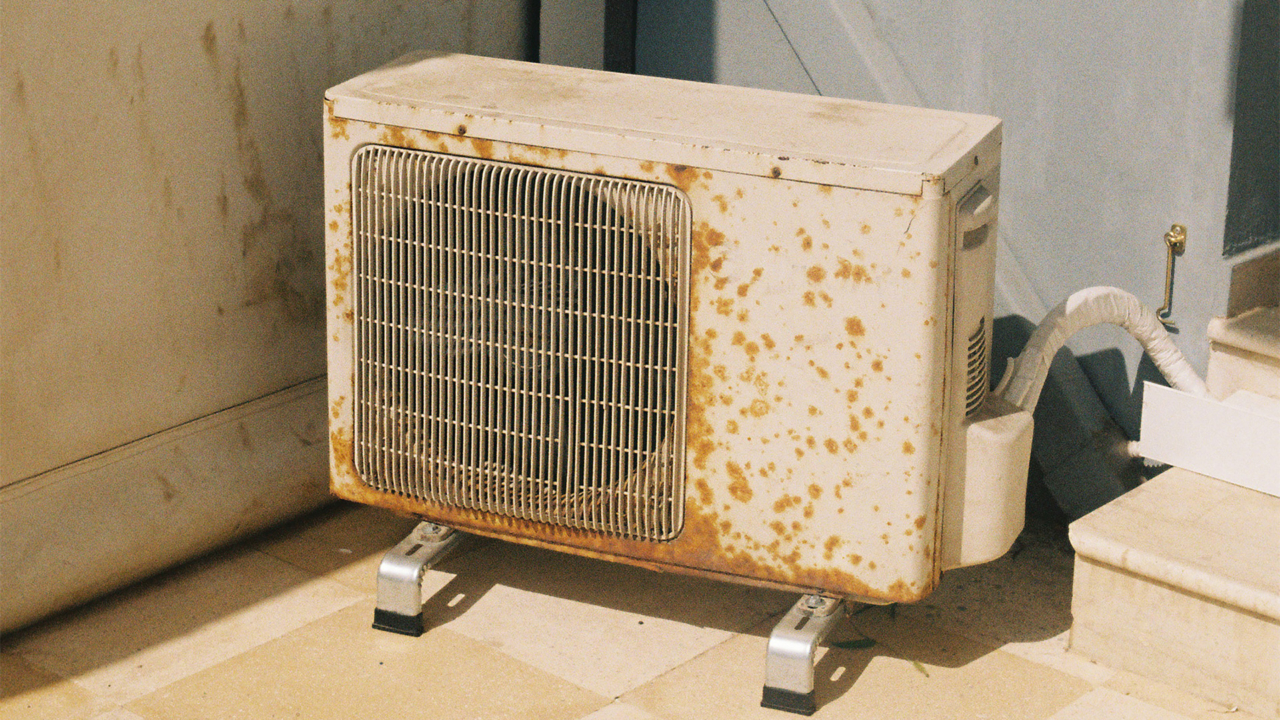

A 2020 federal energy survey of residential homes found that nearly a fifth, or 16.9%, of a household’s power went to air conditioning uses. Compare that to lighting or refrigeration, at 10.3% and 7%, respectively, of a household’s power demand. And since quite literally almost every American home has some form of air conditioning, a proportion that has grown by 56% between 1980 and 2020, a staggering amount of electricity is dedicated to artificially lowering the temperature. Even for a home appliance, there’s enough consistent demand that numerous direct-to-consumer companies, like July and Windmill, have popped up to provide new options they say are sleeker, more aesthetic, and more efficient than traditional window air conditioning units and heat pumps.

Plus, regardless of what power is being used for, “heat impacts the entire electricity sector in a number of ways,” says Sam Gomberg, a senior energy analyst with the Union of Concerned Scientists. “It’s not just the power plants; it’s the wires, the substations, the transformers [that] all struggle to operate efficiently as the temperature rises.”

“We’re facing a world in which Americans have a much larger air conditioning carbon footprint than any other region, because in the Global South, there’s still a lot of inequitable resource allocation.”

That has created a concerning catch-22 for the health of our planet and everything living on it. More and more humans are feeling the impact of warming temperatures; last month, an analysis by Climate Central, a non-partisan group of scientists and communicators researching climate change, shows that 4.97 billion people around the world were directly impacted by extreme heat; 165 million in the U.S. The majority of affected communities, however, were located in the Global South—specifically, in lower-income countries in Asia, Africa, Latin America or Oceania—who don’t have the same access to mechanical cooling as those in the Global North.

“We’re facing a world in which Americans… have a much larger air conditioning carbon footprint than any other region, because still in the Global South, there’s still a lot of inequitable resource allocation,” says Lindsay Baker, the chief executive officer of the International Living Future Institute. “People around the world aren’t going to be building McMansions and setting the air conditioning to 65 like in Las Vegas.”

As extreme heat inches closer to becoming the standard kind, observers of the building decarbonization space fear more of the affected communities who are able to, will want air conditioning to reduce the physical discomfort of high temperatures, perpetuating a positive feedback loop of emissions and power demand.

In the Global North, “we operate as if comfort in climate-controlled interiors—but also in consumption, food waste, and travel, etc.—is a human right,” wrote Daniel Barber, head of the architecture school at the University of Technology Sydney and an architectural historian, in a 2019 essay, After Comfort, on the climate-air conditioning paradox that affects sensitive and at-risk groups. “But the global carbon sink, which is directly related to the provision of comfort, is past full.” He and others are quick to point out that “comfort” isn’t the same as “health and safety” for groups that are sensitive or at-risk for heat-related medical issues .

Barber argues that, in the U.S., the situation can be alleviated in part through a shift in the American cultural expectation around physical comfort, albeit an admittedly substantial one. He notes that, while there are “very real needs in terms of public health, in terms of life and death,” most air conditioning use isn’t going toward critical needs. For those not in-need, relative discomfort, he suggests, must be on the table for us to shift away from an unsustainably comfortable, consumerist society.

“In the maternity ward, in an archive, there’s places where it’s needed,” Barber tells Atmos. “But if you’re coming home from work and sitting around for a couple hours before going to bed, how much air conditioning—or heating, for that matter—do you really need? How can you adjust your habits, expectations and ways of life… How can we live differently in relation to these mechanical systems?”

The idea of not flicking on the air conditioner when it’s hot out is surely hard for most people, even for those who aren’t in sensitive or at-risk groups where A/C is a medical necessity, to fathom.

“How can you adjust your habits, expectations and ways of life… How can we live differently in relation to these mechanical systems?”

“We do know now that, scientifically, air conditioning is addictive,” says Baker. “It’s something that as we have more exposure to it, and as our bodies get acclimatized to it, we literally need it more.”

To be clear, no matter the cultural tool set you’ve been dealt, Barber isn’t exaggerating by framing extreme heat situations as a “life or death” problem. The body can’t handle extreme heat, although the exact temperature varies depending on personal tolerance, age, pre-existing health conditions, exposure, humidity, and other weather factors. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says that extreme heat can lead to brain and organ damage, heat exhaustion, and heat stroke, as well as the exacerbation of cardiovascular, respiratory, cerebrovascular and kidney problems. Relatedly, extreme heat also affects your cognitive performance, which can impact how well you do your job, explains Joshua Graff Zivin, a professor of economics at the University of California San Diego with an emphasis on climate and air pollution impacts.

“It may be that, when you’re exposed to extreme heat, you don’t die, don’t go to the hospital or the doctor—maybe you don’t even know you’re not feeling particularly well—and yet you turn up at work and only finish 80% of what you normally would get done,” he says. “That is a serious economic consequence.”

Some people, like kitchen staff, warehouse workers or farm hands, face more harsh work environments during extreme heat than others. “The temperature in a busy restaurant kitchen is completely disconnected from the experience you’re having, sitting at your table waiting for your food to arrive,” Graff Zivin says. (And for those who are imprisoned and have no freedom of movement, it’s not uncommon to suffer through heat waves in jails that lack air conditioning.)

Many of the people working these types of jobs are also migrants or from low-income backgrounds, further perpetuating the equity issue inherent in who can afford to cool down and who cannot. And once those workers get home, paying for air conditioning is challenging, too. Heightened power demand can lead regulators and power utilities to undertake what Gomberg calls “draconian solutions” that inadvertently punish the poor.

“You have some communities where they are really trying to avoid life-threatening situations, and raising the price of electricity and making it harder for them to do that is not a solution that I’m going to advocate for,” he says. Mitigating this demand through power prices, he adds, “needs to be done in a very thoughtful way so that you are not further marginalizing disadvantaged communities.”

Cooling down helps reduce or eliminate the health risks, which means we still need something to keep us safe during the hottest days of the year.

To Barber, that should include city- and state-level policy shifts that aim to curb cooling demand, like encouraging the use of cooling centers. He hopes that cities do for cooling demand management what some have done for readjusting expectations of drivability in urban cores and city centers. “It just becomes a very different place, and it becomes that place over time by virtue of testing things out and making them work, and by having that clear sense of purpose around cultural change,” he tells Atmos.

It also means there is room for the industries that build and cultivate our homes to create changes that reduce how much we need mechanical cooling. Instead, they can invest in designing and building housing that increases the efficiency of natural cooling techniques. Gomberg, who has reservations about a cultural shift in physical discomfort to address cooling energy demand because of equity and safety concerns, says “there is still a lot of low hanging fruit out there in terms of energy efficiency and that there is a lot of cost-effective… improvements that can be made to our existing building stock.”

If the point is to keep human bodies safe and healthy, we don’t need to cool down an entire home to do that.

Specifically, he wants to see better support for more-stringent cooling efficiency standards at the federal level, as well as more avenues for low-income residents and small businesses to afford to make efficiency upgrades and cool their homes.

“That is where I think you do need thoughtful government programs to help narrow that gap and address some of those inequities and make sure that we all get to live in comfort,” he adds. To that end, Gomberg says it’s critical to communicate to representatives in the spaces that make these policies—from state legislators to grid operator stakeholders to utility regulators—for us all to better understand what their plans are to address increasingly hotter temperatures.

Baker wants to see more buildings constructed using techniques that were traditionally suited for the climate and environment at-hand, and less architecture that requires air conditioning to be livable.

“Think about adobe houses in the Southwest, louvered architecture in the Caribbean, the natural stack cooling effect of wind towers in the Middle East,” she says. “We have learned through generations how to build homes and buildings that are comfortable for our bodies using techniques that were passed down and that are human-scale technologies.” She adds that the “challenges that we face when it comes to comfortably sheltering ourselves now really start at the intersection of globalization and urbanization.”

In other words: “it is not a coincidence that glass towers in cities with no operable windows started emerging after the invention of air conditioning,” Baker explains. “They were not possible before… because they would have been too hot for anyone to live in.”

But seemingly basic building stock improvements are among the “less sexy things” to talk about in the climate mitigation space, Baker says, but adding new windows, insulation, and roofing materials to prevent conditioned air from escaping will help reduce how much energy is needed to keep a space cool.

Plus, she notes, if the point is to keep human bodies safe and healthy, we don’t need to cool down an entire home to do that. Dehumidifiers and radiant surface cooling can do that at a much lower energy cost than an air conditioner—as can a simple ceiling fan.

“If I could make a ceiling fan sexy, I would do it,” Baker says. “It’s definitely a great way to keep yourself cool.”

The World Is Getting Hotter. Air Conditioning Could Make It Worse.