Words by Zoe Suen

photographs by toshio ohno

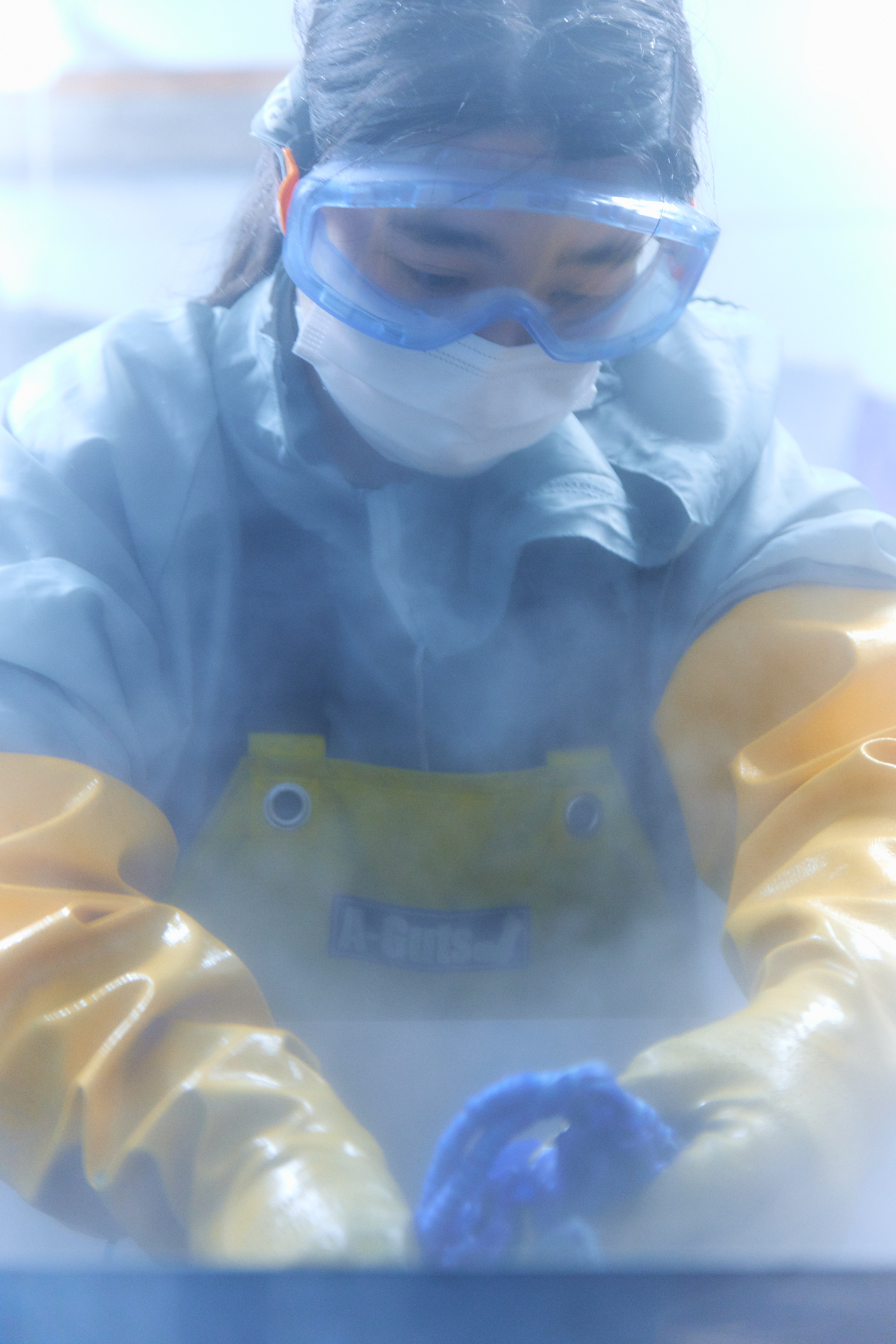

Upstairs at the Narumi Shibori Museum in Arimatsu, a historic town on the outskirts of Nagoya, two women kneel on cushioned tatami mats. Their nimble hands work at separate styles of cloth binding, a step that precedes the centuries-old dyeing technique known as Shibori.

It’s a damp day in early spring; I’m part of a troop of journalists, buyers, and designers touring the sleepy town for Tokyo Creative Salon, an annual event working to promote Japanese craft and design to both a local and global audience. Days prior, we visited woodcutting workshops and denim manufacturers in Hiroshima and Nagoya, angling for a glimpse of experts at work.

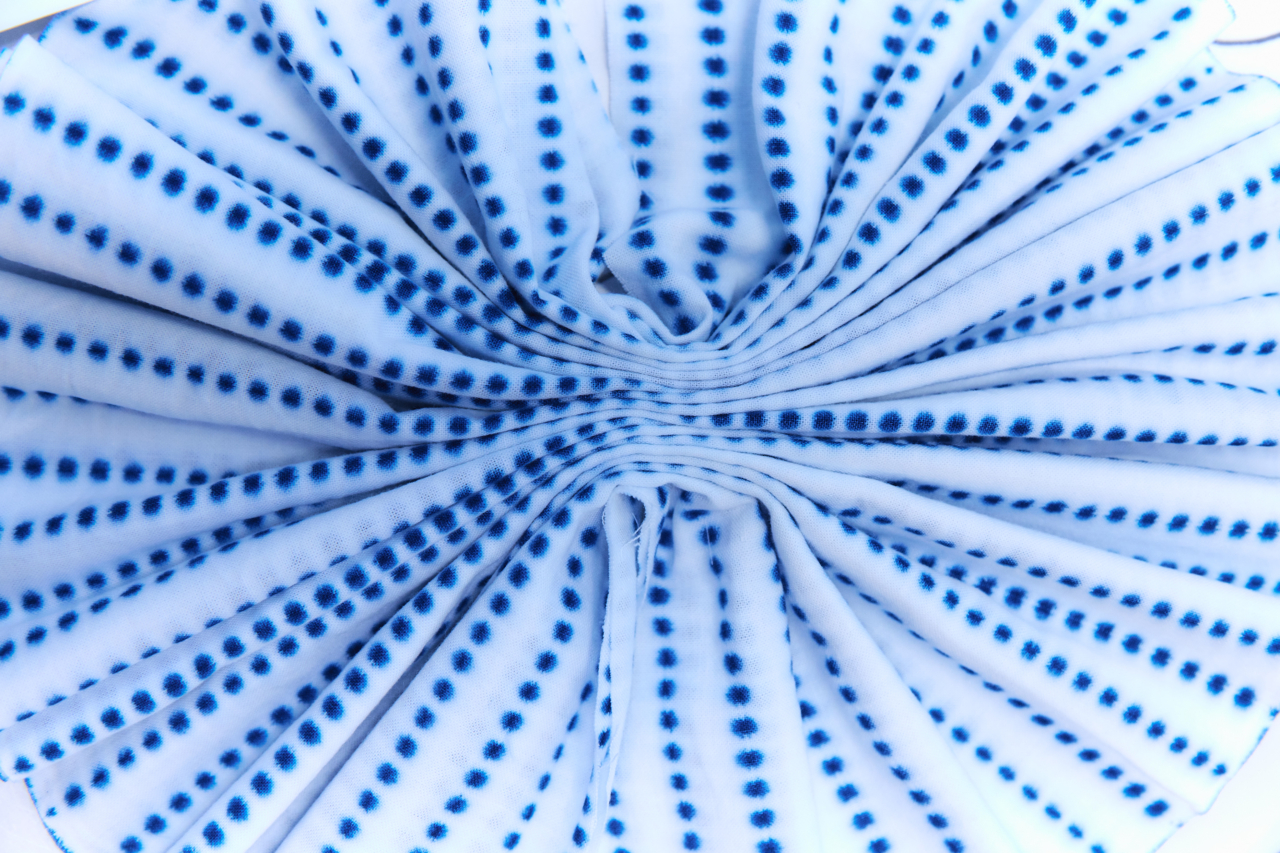

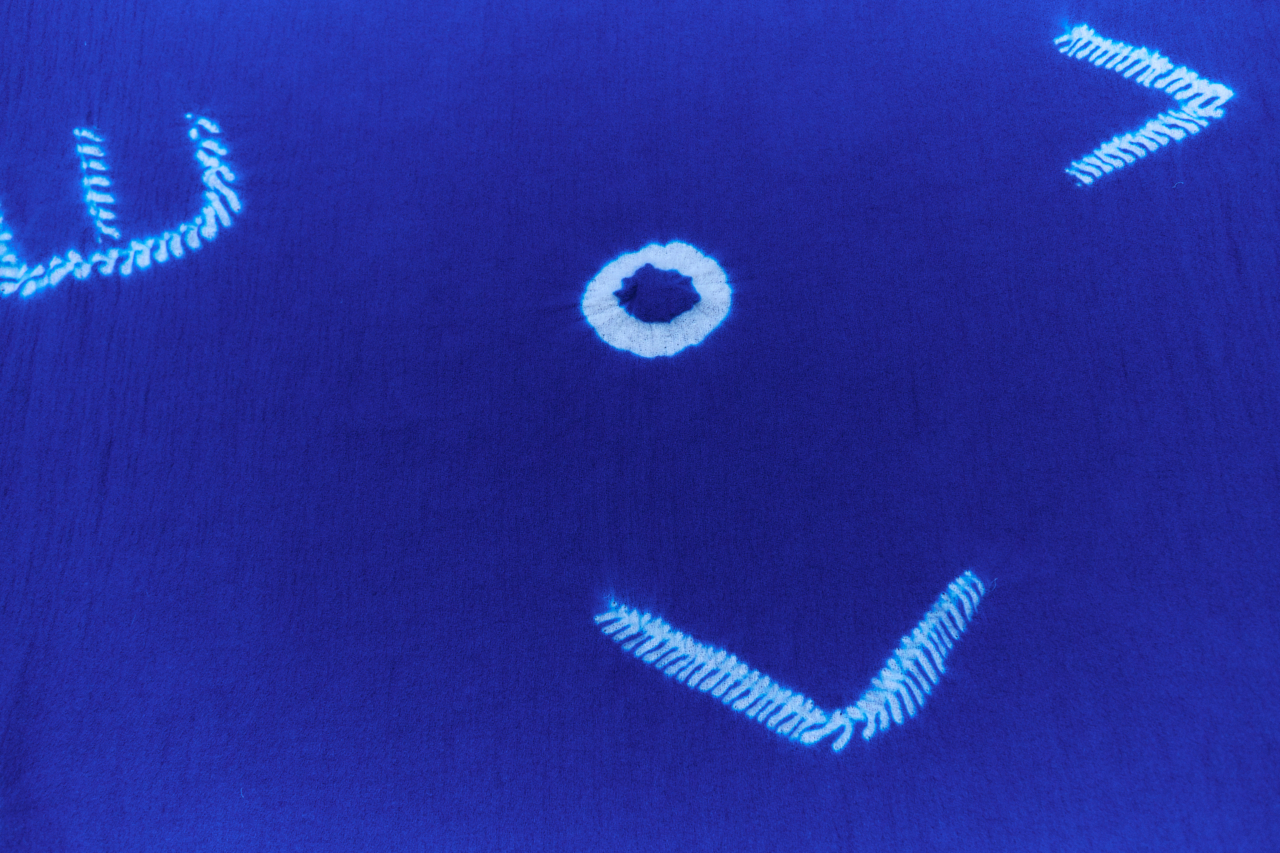

Arimatsu, which sits on the ancient Tokaido route that links Kyoto with Edo (now Tokyo), is famous for Shibori. A small huddle has formed around the artisans, both of whom sport faded tie-dye sweatshirts and sit aside framed samples of the techniques they’re demonstrating. On the left, Fujiwara-san forms tight piques by sewing together dots on her fabric in a method known as Moira; the result, once dyed, is a kind of reverse pointillism. Next to her, Matsuoka-san works the Tatsumaki technique by coiling her yarn around a meticulously pleated swathe of fabric. Gathered and bound a certain laborious way, the fabric exposed to dye forms thin vertical stripes resembling tall bamboo shoots.

Fujiwara-san, aged 87, has been practicing Shibori since she was seven; Matsuoka-san, who married into the craft, recently turned 80 and has been working as an artisan for half a century. In age and experience, they’re exemplary of Japan’s handicraft community—one that is rich with history and expertise, but faltering amid digitization, ultra-fast fashion, and a rapidly aging population.

“Japanese craft is at a very dangerous place,” Hiroyuki Murase tells me during our trip. “Things can still change, definitely, but the turning point is now. Otherwise, it’ll be too late.”

An Arimatsu native, Murase is the brains behind Suzusan, a brand he built out of his family’s now fifth-generation Shibori practice, which has sold textiles to the likes of Yohji Yamamoto, Comme des Garçons, and Issey Miyake. The label bolstered the family business by weaning it off subcontractor work and stabilizing the family’s income all the while adapting to meet new demands; techniques were updated for slouchy sweaters, bouclé throws, and shirt-dresses instead of the traditional kimonos and yukatas fewer and fewer people buy.

“When we started [Suzusan] in 2008 my father was the youngest artisan in Arimatsu and he saw no future in Shibori,” says Murase, who in 2023 began working with Tokyo Creative Salon to broaden the event’s focus beyond Japan’s capital city. Now, his team is full of younger 20 and 30-somethings who were drawn to the business’ luxury links and the promise of more fulfilling work.

But Suzusan is an outlier: most craft businesses in Japan consist of between one and five employees, with the bulk of them aged over 50.

As a family member, Murase was uniquely positioned and incentivized to adapt his father’s business to a changing world. Having studied at Düsseldorf’s Academy of Fine Arts, he made a conscious decision to build its wholesale network in Europe before bringing it back home. “If craft businesses set their goals within the Japanese market, they won’t survive—this is very clear,” says Murase, who continues to be based between Germany and Japan.

“Japanese craft is at a very dangerous place. Things can still change, definitely, but the turning point is now. Otherwise, it’ll be too late.”

But it isn’t as easy for other storied artisans to hire young employees with a global mindset. Even if the desire is there, the money isn’t—at least at the outset. It’s a chicken and egg fix: younger Japanese want meaningful jobs, but need liveable salaries, particularly as the yen depreciates and salaries dwindle nationwide. Businesses need young employees to adapt, but must first drive growth in order to pay them.

For elder artisans who have been doing this work for decades, thinking beyond Japan and beyond traditional product categories is often out of the question. Meanwhile, language barriers, a lack of experience outside the country’s unique business culture, and policy infrastructure that pushes Japanese craft businesses to choose between long-practiced traditions and adaptation all contribute to their uncertain futures.

The preservation of Japanese craft is overseen by an Agency for Cultural Affairs that determines whether or not factories and workshops can attain special certifications for techniques deemed “intangible cultural properties”—these in turn provide much-needed leverage for negotiating favorable pricing. The criteria, however, are rigid, according to Seiichi Saito, the general creative director for Tokyo Creative Salon and cofounder of creative agency Rhizomatiks.

“They have to do things the same way, using the same traditional techniques,” he says, raising the example of crystal craftsmen in Yamanashi, a prefecture that has gone from housing 400 studios to under 10. “They can’t use [new or] high-tech applications such as polishing crystal with machines instead of fine sands.” And though certification can greatly increase a business’ chances of receiving funding from the government, even those with the Agency’s stamp of approval are struggling as budgets shrink.

Meanwhile, the country’s much larger Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry is responsible for the design and craft industries with a view towards the future, and industrial applications—the Ministry has its own designation of “traditional craft,” but rather than purely preserving techniques and items from an academic point of view, the body subsidizes development and growth. There’s also a conceptual gap between the two bodies’ understandings of “traditional crafts,” with the Ministry centering on everyday use and the Agency recognizing artistic works.

In practice, many certified craft businesses don’t apply for funding from the Ministry as they can risk losing accreditation from the Agency if they embrace the technologies and industrial innovations the former encourages, though an overlap is in theory possible. It doesn’t help that, according to Saito, the two bodies rarely see eye to eye.

“The Agency for Culture Affairs is always thinking about the past, and the Ministry of Economy is always thinking about the future,” he says, leaving a chasm in between and forcing artisans to choose between tradition and survival—when all they know is the former.

This current dynamic echoes what unfolded during and after Japan’s post-war industrial boom.

Pre-war, Japan was a rich tapestry of handicrafts, with each region’s specialities reflecting its micro-ecosystems and natural resources. By the 1960s, industrialization was in full force and the likes of Toyota (which had its start as an automatic loom maker) aimed for global domination. The prioritization of efficiency and low costs forced craftspeople to choose: they could stick to their techniques and products or buy machinery and adapt.

One such business is Hiroshima-based denim manufacturer Kaihara, which handcrafted indigo-dyed fabric for kimonos and sarongs pre-war, but pivoted to machine-made denim in the 1970s. Now, the business hires some 600 people in Japan and runs a factory in Thailand. According to its website, the manufacturer—which has worked with Levi’s since its foray into jeans—has a 50% share of Japan’s denim market.

“For a long time, the design industry tried to make shopping a black box…they didn’t need to tell us what was happening inside, so we’re far behind when it comes to knowing the process.”

So, has the die already been cast for Japan’s slow fashion makers who haven’t adapted to a faster-paced system? The answer is complicated.

Within Japan, interest in slow fashion and handicrafts is on the rise, particularly in the wake of the pandemic and an uptick in domestic travel. In tandem, a cohort of predominantly younger people are increasingly aware of the environmental and social costs of fast fashion: according to a 2023 Rakuten survey, the percentage of 20-somethings who’d buy sustainable fashion (50%) was the highest, while 60-somethings showed the least interest (31%). Burgeoning inbound tourism is also helping.

But compared to Europe, there’s far less stigma around overconsumption. “Fewer people pay attention to issues around fast fashion,” says Saito. “For a long time, the design industry tried to make shopping a black box, where you’d press a button and get a coffee—they didn’t need to tell us what was happening inside, so we’re far behind when it comes to knowing the process; the back story.”

Investment from European luxury groups can help keep local crafts businesses afloat. After all, Europe’s luxury brands have long been admirers of Japanese craft: LVMH’s Métiers d’Art division inked a partnership with denim-maker Kuroki last year, months after Gucci launched handbags fashioned from 327-year-old textile mill Hosoo’s lush silk brocade. “Local brands can’t order 10,000 meters of fabric, but European brands can reach higher quantities and order fabrics at a higher price point,” says Murase.

For independent Japanese brands, however, this power imbalance can hurt. “A very famous brand uses the same factory as us,” says Yota Toki, the designer behind his namesake brand and the founder of Tokyo-based retailer TOKIS. “They order large quantities, so the price for us goes up, and we’re less of a priority. They have a lot of leverage.” From Toki’s perspective, luxury houses use Japanese techniques and craftsmanship as marketing tools.

But even when collaborations are one-offs rather than long-term, Murase sees them as overall positive for the country’s craft scene as they offer makers an opportunity to promote themselves to a larger audience. That’s only an option if artisans can advertise who they supply. Like many aspects of the luxury supply chain, the question of who makes what for whom is often shrouded in secrecy. At Kaihara, for example, we’re given the names of several luxury clients before being asked not to publish them.

More often than not, this opaqueness—a global dynamic that is pervasive in craft hubs like India, for one —works to protect luxury’s “Made in Europe” branding, which masks globally entrenched, often colonial Eurocentric power structures.

It’s no secret that luxury exploits poorer communities for the benefit of already-wealthy executives and brand owners; the latest Bloomberg exposé tying Loro Piana’s $9,000 vicuña sweater to unpaid Indigenous workers in Lucanas Peru is just one recent example. But the hush-hush dynamic is also a result of competition between brands, and their overarching desires to project exclusivity, when their denim is actually made in the same factory as a more affordable pair of Levi’s jeans.

In practice, luxury’s lack of transparency has an outsized impact on smaller makers. Murase’s family business, for instance, was able to bring in younger employees by publicizing its work with brands like Dior, but it’s rare that suppliers feel comfortable sharing the major brands they work with, meaning they’re often precluded from the benefits of those affiliations.

Ultimately, the missing piece of the puzzle, according to both Murase and Saito, isn’t money or young hires, but shifts in mindset for craftspeople—who need to see the potential in their techniques for new products, consumers, and global markets.

“Nowadays, people think that a bag you can’t fit anything in should cost €5,000 [or] €10,000 because of its brand name, even if you can find it in every city,” says Murase. “We have to show the value of local and unique craft.”

But positioning Japan-made slow fashion as not only valuable but luxurious could prove a gargantuan task. “Japanese people don’t recognise the value [of domestic craft] by themselves,” says Murase, who at Suzusan’s inception made a point to only sell to overseas stockists for several years and stood his ground when Japanese onlookers said his prices were too high. After the brand was stocked by European boutiques, Japanese shoppers saw Suzusan in a new light. “It’s a boomerang effect—I just want to ask them, ‘is that Louis Vuitton bag worth it?’”

According to Saito, this mentality, like the current state of Japanese craft, can be traced back to Japan’s defeat in World War Two—he remembers asking creative director and Muji advisory board member Kazuko Koike about the phenomenon during last year’s Tokyo Creative Salon. “She said that since 1945, we’ve always seen ourselves as behind, and European and American products as better. So, we try to catch up and go beyond, which has remained a target for over 50 years.”

It’s a complicated and deep-rooted legacy to tackle. But perhaps, as a result of Japan’s burgeoning soft power and popularity as both a domestic and global tourism destination, artisans will be able to see their long-honed crafts in a new light. “The arrows are directed in[wards], rather than out[wards],” says Saito. “We’re in an interesting moment right now.”

The Uncertain Future of Japan’s Slow Fashion Makers