Words by Kate Nelson

photographs by will warasila

For far too long, citizens of the Blackfeet Nation have been vanishing without a trace.

Growing up on the expansive Indian reservation in northwest Montana, Haley Omeasoo (Hopi/Blackfeet) witnessed community members go missing and their cases go cold—including the case of her relative and former classmate Ashley Loring HeavyRunner. Still unsolved nearly seven years later in 2024, her classmate’s disappearance prompted 27-year-old Omeasoo to establish Ohkomi Forensics, the first Indigenous-owned forensics organization dedicated to addressing the Missing and Murdered Indigenous People (MMIP) epidemic.

“It’s this awful normalcy to see all these young people go missing,” says Omeasoo, who learned of HeavyRunner’s disappearance from a missing person poster. “Ashley was really my motivation for going into this field because I’ve seen how her case has fallen through the cracks. It possibly could have been solved a long time ago, but we just don’t have the proper resources on the reservation to do that. I hope that Ohkomi can be that resource for Indigenous people, because right now there’s this huge gap between what families need and what law enforcement is doing—or not doing.”

In the nationwide MMIP crisis, Montana has one of the highest disappearance rates. Native Americans make up just 6.2% of the state’s population yet account for 30.6% of missing person cases, according to the Montana Department of Justice. Although it’s hard to fully encapsulate the magnitude of this epidemic due to inconsistent reporting and data collecting methods, national research has found that murder is the third leading cause of death for Native women, who also experience outsized violence rates in the United States.

“I hope that Ohkomi can be that resource for Indigenous people, because right now there’s this huge gap between what families need and what law enforcement is doing—or not doing.”

It was upon moving to Missoula to attend the University of Montana that Omeasoo noticed a stark contrast in how missing persons cases are handled on and off the reservation. She had grown used to seeing ineffective—even nonexistent—investigations, an all too common phenomenon within tribal communities due to a variety of factors, including jurisdictional issues, insufficient funding, inadequate training, and a lack of cultural understanding. Failed by a flawed system, grieving families are often left to look for answers on their own.

Omeasoo is currently pursuing a PhD in forensic and molecular anthropology and is set to graduate in May 2025. But she knew she couldn’t wait until then to take action. In January she officially launched Ohkomi—meaning “to use one’s voice” in Blackfeet—to help families still grappling with cold cases get justice and closure. For now, she’s focused on advocacy and fieldwork, including search and excavation services.

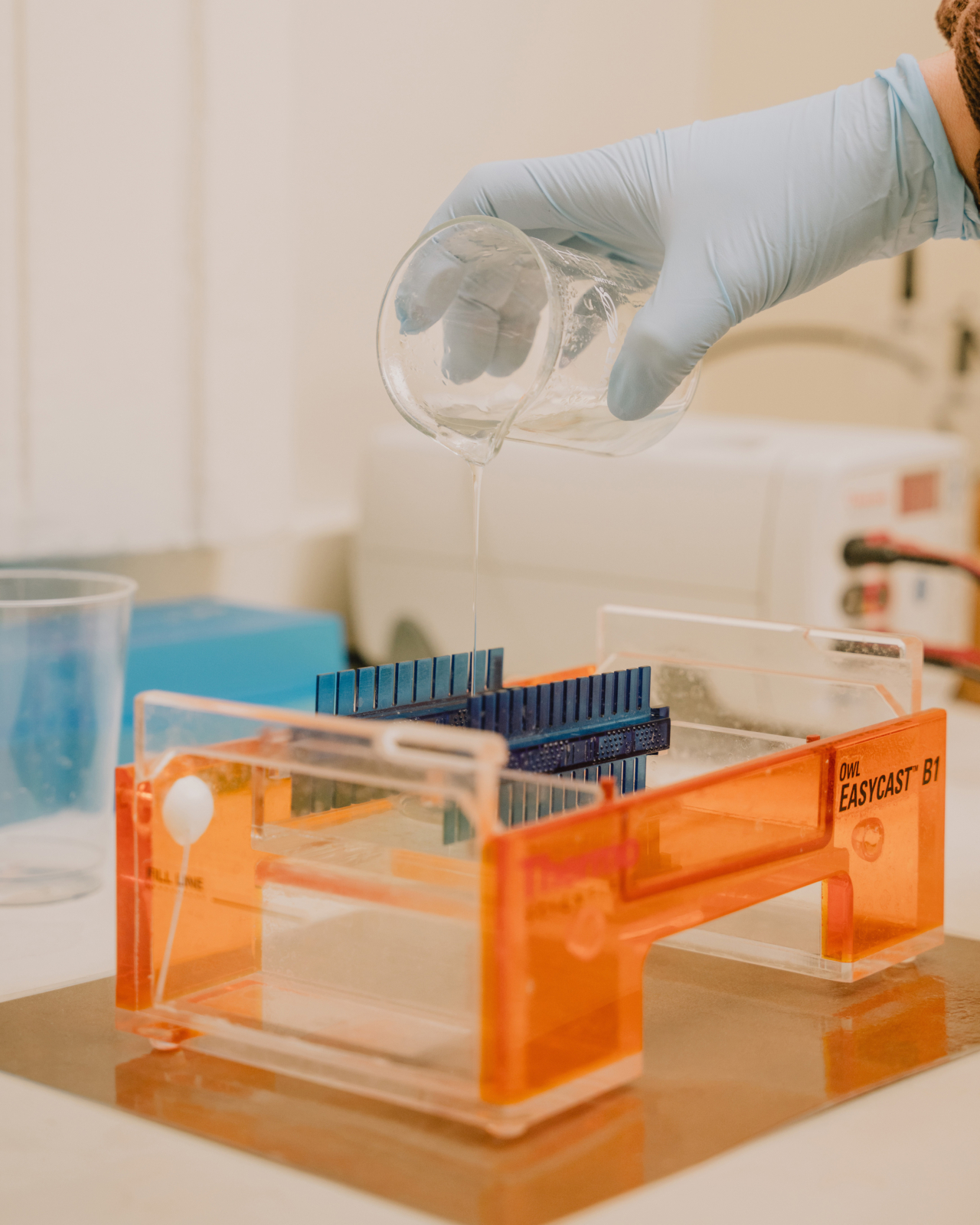

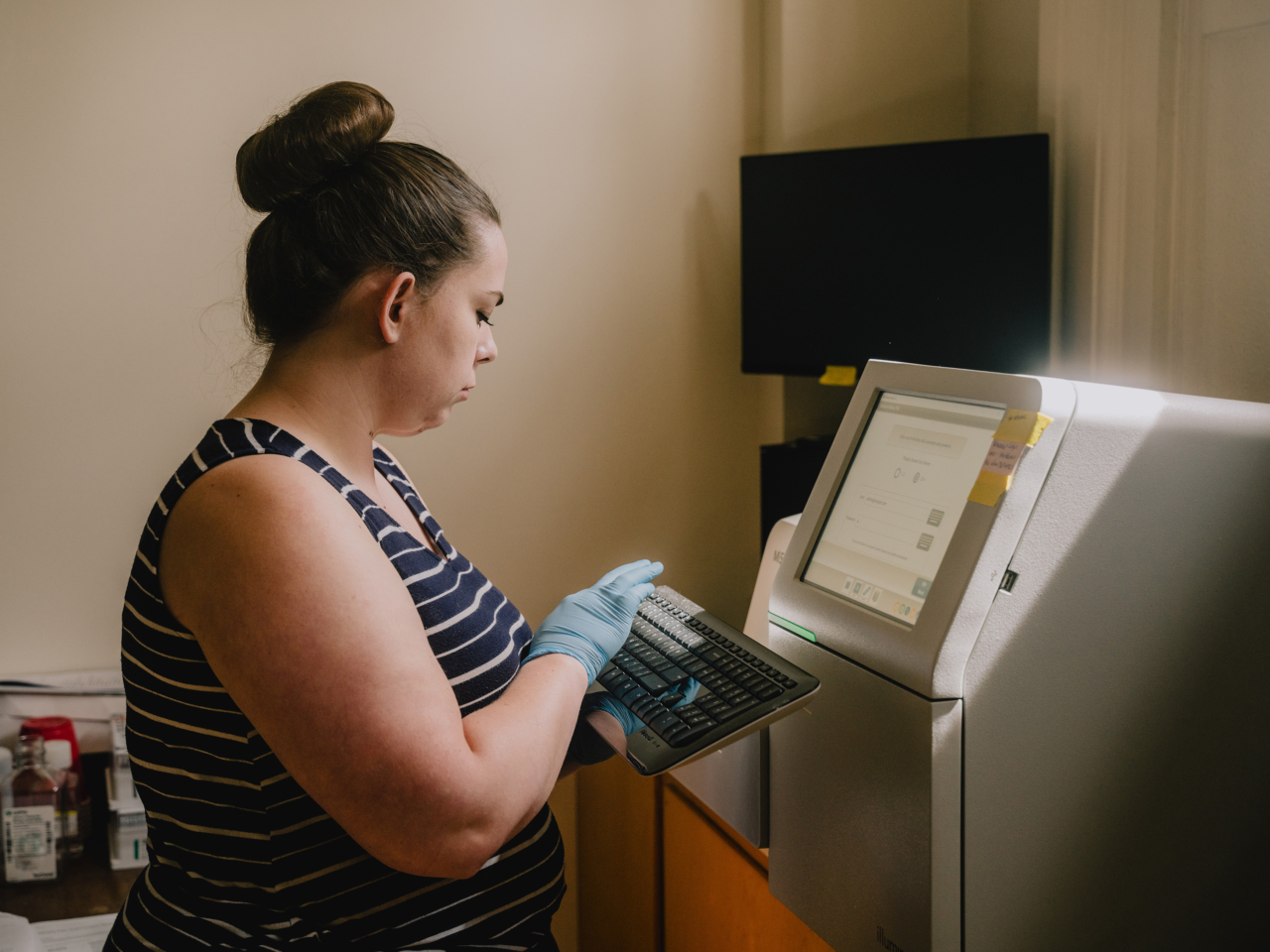

The long-term goal is to establish a forensics lab on the Blackfeet reservation, which Omeasoo aims to accomplish within the next few years. In the meantime, she is partnering with the University of Montana forensic anthropology lab to provide DNA testing, pathology reporting, and other human remains analysis that allows her to build a biological profile of a victim. That includes identifying sex, stature, approximate age, trauma signs, and the like to determine who someone was and what happened to them.

Ohkomi’s current forensics team consists of Omeasoo and her fellow graduate students, who will join her out in the field back on the reservation this summer. Of a team of 10, she is the only Indigenous individual. That puts the onus on her to educate her non-Native peers—as well as any law enforcement counterparts—about cultural beliefs and values that must be taken into account in these highly sensitive situations.

“There’s this barrier, because non-Natives don’t understand reservation life, our cultural beliefs, and our traditional knowledge,” says Omeasoo, who is developing cultural protocols to be used in tandem with scientific protocols. “With Ohkomi, I’m trying to build that bridge between Native and non-Native people. That cultural [sensitivity] needs to be at the forefront of everything, because we don’t want to do more harm than has already been done.”

Further complicating matters are antiquated anthropological methods that “are very racist in how they categorize people,” as Omeasoo explains, as well as data sovereignty concerns over who owns the ascertained information. To that end, she is committed to using state-of-the-art techniques that can extract DNA without damaging remains and putting in place culturally appropriate memorandums of understanding about data collection and usage.

Given the intersectionality of her identity and her expertise, Omeasoo feels uniquely equipped to navigate these complex issues. “You really want to make sure that you’re representing the data [in a way that is] in favor of the people you are researching,” she says. “So many Indigenous people don’t trust law enforcement or researchers taking their DNA and information because they don’t know what’s going to happen to it after that. As both a researcher and an Indigenous person, I definitely have an advantage.”

For Blackfeet citizens affected by the MMIP crisis, Ohkomi serves as a beacon of hope in what has begun to feel like a hopeless situation. “We have too many unsolved murders and missing loved ones; it’s the same story over and over again just with different names,” says Rhonda Grant-Connelly. “I got so excited when I learned about Haley and her organization, because this is something I’ve been fighting for for years.”

Grant-Connelly has experienced loss threefold. Her brother was murdered in 1998. A nephew was murdered in 2014. Most recently, in 2016, another nephew, 21-year-old Matthew Grant, went missing and was found murdered a couple weeks later.

Since then, Grant-Connelly has been seeking justice and having conversations with other Blackfeet families who are similarly searching for answers—more than 60 families, to her count. To try to stop this “pattern that has plagued the reservation for decades,” she founded the nonprofit Blackfeet MMIP last year alongside Wilma Flurry and Carlene Old Person, both of whom have experienced the loss of a child.

“So many Indigenous people don’t trust law enforcement or researchers taking their DNA and information because they don’t know what’s going to happen to it after that.”

Like many of her fellow tribal members, Grant-Connelly has become jaded about broken promises from state and federal lawmakers and agencies to address Montana’s MMIP crisis. “We have put our trust in these individuals, but nobody is listening and nothing is being done,” she says. “We have to live through the torment of having our loved ones killed then having the killers walk among us with no arrests being made. In order to make things better, the whole system needs to change.”

She and other community members have sought support from the likes of tribal lawyer and MMIP advocate Erica Shelby (Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes) and Seasons of Justice, a nonprofit that provides funding to help solve missing person cold cases. Grant-Connelly is optimistic that, in concert with these entities, Omeasoo can effect meaningful change—not only when it comes to forensics analysis but also in terms of accountability and training.

“I really think Haley will be able to help hold [law enforcement] more accountable and provide training for them,” says Grant-Connelly, who has gathered countless anecdotes about evidence mishandling and similar atrocities. “Many of them don’t have the proper knowledge to find and preserve evidence [and] then write a report. I believe she’ll be more compassionate toward her own people and handle our cases in a more professional manner.”

For its part, the Montana Department of Justice recently launched an updated missing persons database and is in the process of appointing members to the Montana Missing Indigenous Persons Task Force, which was developed in 2019 and extended for another decade during last year’s legislative session. As far as a potential collaboration with Ohkomi Forensics is concerned, Montana Department of Justice communications director Emilee Cantrell says it is “too soon to tell” if the task force will pursue such a partnership.

Even with enthusiasm from the Blackfeet tribal council and larger community, Omeasoo still has a long road ahead of her to get Ohkomi fully up and running. Right now, she’s working on three cases while building relationships with local law enforcement officials, who she says are “overworked and understaffed.” She’s also tapping partner organizations that can provide complementary resources such as cadaver dogs, underwater and ground-penetrating radar drones, and the like. Finally, she’s trying to fundraise to support current and future initiatives, such as building the on-reservation forensics lab.

That’s all in addition to her PhD workload, which is focused on creating a tribally owned, controlled, and maintained genetic database from living Blackfeet community members. Omeasoo believes the database could prove instrumental not only in helping mitigate the MMIP crisis but also acting as a “stepping stone” for repatriating unidentified ancient Indigenous remains currently held by universities, museums, and other institutions.

Despite the obstacles she faces, Omeasoo remains steadfast in her resolve with the goal of creating a more peaceful world for future generations, like her two young sons. With Ohkomi, she aims to inspire Native youth to pursue careers in these fields while also developing a blueprint for Indigenous communities across not only the country but the globe.

“It’s difficult being one of the first to take on this work, but I really hope that we can serve as a model for tribes even on an international level, since I’ve been talking with people from other countries that are experiencing similar issues,” she says. “Just here in Montana, a lot of cases have been mishandled, and I’m hoping we can start to solve some of those. In an ideal world, we wouldn’t have any more cases to work on because all of our knowledge and methods would be implemented into a proper protocol that works for everybody. But that’s not going to happen overnight.”

“We have too many unsolved murders and missing loved ones; it’s the same story over and over again just with different names.”

Back on the Blackfeet Nation, fierce advocates like Grant-Connelly are breathing a sigh of relief knowing that young leaders like Omeasoo are stepping up to help combat the MMIP crisis in Montana and beyond.

“I want our grandkids to have a better future—one where they don’t have to worry about going out after dark, like I do now,” Grant-Connelly says. “What’s taking place is disheartening, but I’m very confident that Haley is going to be able to solve so many cold cases. She’s going to help mend a lot of broken hearts here on the reservation.”

The Native-Led Forensics Lab Dedicated to Solving Missing and Murdered Indigenous People Cases