Words by Romina Cenisio

Photographs by Daniel Shea

music by peter m. murray

video by Sofie Kjørum Austlid, daniel shea

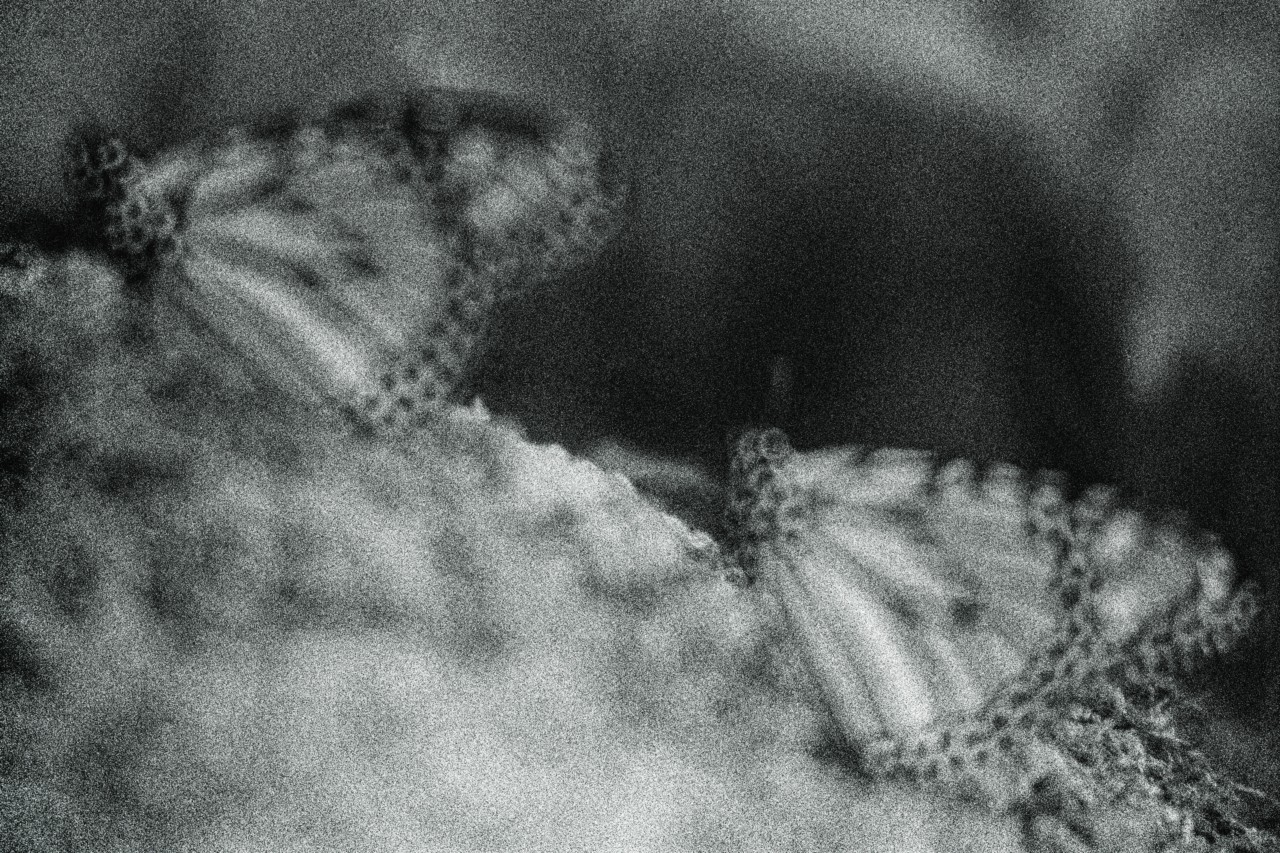

As I lie on the ground with my eyes closed, a sound reminiscent of light rain surrounds me, subdues me. Yet unlike the steady drum of rain, the sound seems to move around from left to right, up and down, in both unison and disorder. At times a ticklish, ASMR sensation overcomes me as the sound gets closer, but no raindrops land on me. Opening my eyes moves me out of this gentle trance, reminding me that there is no rain; rather, there are millions of monarch butterflies shimmering overhead. Bursts of bright orange are so thick that at times they shield my eyes from the blazing sun. Some of them cascade gently to the ground, fluttering near my horizontal body, jittering their wings as they wait for the sun’s warmth to lift them into flight once more.

It’s late November, and I’m in Cerro Pelón, a mountain range straddling the border of the Estado de México and its neighboring state, Michoacán. Just two and a half hours west of Mexico City, the most populous city in North America, is the Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve, a protected region of 217 square miles. In the rugged, subtropical coniferous forest of the Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt at an elevation of 11,500 feet, I am witness to one of the most incredible natural phenomena on Earth: the monarch butterfly migration.

Gazing at the clouds of monarchs, it’s easy to imagine them as infinite. But as Monika Maeckle, founder of the Texas Butterfly Ranch, described solemnly, “From the perspective of someone who’s witnessed this for 20 years now, it used to be these dramatic pulses of monarchs…[but now] we’re seeing more of a dribbling constant.” A knot forms in my throat as I realize that what I’m seeing, though incredible, is a mere fraction of what once was. Obtaining an accurate count on the butterflies is a moving target. It is difficult to get good numbers on how many are left and how fast we are losing them. In 2014, the International Union for Conservation of Nature estimated that the eastern population of monarchs had declined around 84% since the 1990s, when their numbers were upwards of one billion. Though the butterflies’ numbers fluctuate yearly, they’ve been trending downward. In July 2022, monarch butterflies officially joined the endangered species list.

From loss of habitat to the instability and unpredictability of climate change, the butterflies’ vast migration that traverses Canada, the U.S., and Mexico faces a patchwork of different threats. In the U.S., habitat loss and pesticides threaten milkweed, a native perennial flowering plant that’s a crucial piece of the migratory species’s survival. It’s the one plant on which monarchs lay their eggs and the one food source for the monarch caterpillars during the spring migration. In Mexico, deforestation due to illegal logging threatens the butterflies’ winter home. With such mounting challenges, the very survival of the monarch butterflies is at stake.

I’d like to say, “Let’s start from the beginning,” but this story has no real beginning and no end. The signature orange-and-black wings edged with white dots of the Danaus plexippus, or the monarch butterfly, have bedazzled humans for centuries. Their awe-inspiring migration is a cycle that repeats each year, spanning three countries. This journey is part of a deeply interconnected symbiosis with other species that ultimately supports us too. From grasslands to roadsides to forests, monarchs are essential pollinators that enrich diversity in flowering plants across North America.

So we will start here, at the beginning of the fall migration in Cerro Pelón, just as this generation of monarchs has arrived at their winter home. While the butterflies seem at home in these mountains, they were not born here and will not live here their whole lives. They were born in the U.S. and have just arrived after traveling up to 2,500 miles, being the great-great grandchildren of the generation that last came to Mexico exactly a year ago. Each fall, millions of monarchs descend from all over the U.S. and Canada east of the Rocky Mountains, creating a tightening funnel through Texas and continuing to their overwintering ground in Central Mexico where they hibernate and roost for about four months. At a cruising altitude of about 4,000 feet and averaging 12 mph, the monarchs fly across our imaginary borders in both spring and fall. From approximately April through October, they move across the Central U.S. up through southern Canada until making their way back down, nectaring and reproducing along the way. The entire population goes from spanning much of the U.S. and Lower Canada to consolidating into less than 20 sites, where they gather in staggering numbers: 10-30 million per roost.

Gazing at the clouds of monarchs, it’s easy to imagine them as infinite.

In order to get to this particular roosting site, I begin in Macheros, a pueblo at the base of Cerro Pelón mountain. I ascend the mountain by horse, an hour and a half uphill. While the evergreen forest is abundant throughout, the terrain changes as I climb from 8,000 to 11,000 feet. Pine forests give way to lush, mossy oak forests. Wildflowers of deep purples and magentas are sprinkled among overgrown flora. There is virtually no brown in sight, even from soil or tree trunks, because moss has overgrown everything. The morning mist lazily swirls and marbles the air. Sunlight beams through cracks in the canopy, revealing speckles of flowers whose bodies lean toward the light, eager to convert its energy into growth. As I continue to ascend, finally arriving at the preferred altitude of the monarch, about 11,000 feet, the one and only tree the butterflies live on emerges: the Oyamel fir tree. Breathing takes a little more effort for us mere humans at this altitude, and the temperature cools and warms with every passing cloud. Like Goldilocks, the monarchs have something here that’s not too cold, not too hot, but just right.

I’m lying next to Joel Moreno, co-owner of Cerro Pelón B&B and third-generation local in Macheros. He’s been running me through the list of threats the butterflies face and the importance they hold to locals, Indigenous peoples, and tourists alike. While Cerro Pelón is pristine and well cared for, it wasn’t always like this. In their Mexico overwintering ground, the monarchs’ primary threat is illegal logging and deforestation. Moreno explained that right over the mountain range in neighboring Michoacán, the forest may not look the same. You might see the jagged trunks of logged trees sticking up from the ground. Though people may assume that all the destruction is nefarious—stemming, for example, from organized crime—the forces behind it are more complicated. “People who do illegal logging in Cerro Pelón are poor people who need to support their family,” Moreno continued. “If I didn’t have this business, that could’ve been me.”

Many people in rural Mexico live in poverty, and locals will sell trees to construction companies or other organizations illegally, sometimes for only 400 Mexican pesos (around $20 USD). The cartel also sells trees, or they plant avocado farms in the forests they clear. In 2020, Homero Gómez González, a passionate and well-known activist who managed the El Rosario Sanctuary, was found dead in a nearby well. Shortly after, Raúl Hernández Romero, another activist, was also found dead. No one has been charged for these crimes, but some locals believe the cartel was sending a message after illegal logging disputes. In Michoacán, even though the biosphere is technically a protected area, cartels and survival commonly take precedence over these protections. Not only does this take away the butterflies’ only winter home in Mexico, but because trees regulate moisture and temperature, logging the pine and oak alter the microclimate that makes the area perfect for the butterflies and other animals to survive. The area is so large that it’s impossible to keep tabs at all times, and there’s no adequate system in place to keep watch.

After years of watching destruction, Moreno took matters into his own hands and cofounded a grassroots nonprofit, Butterflies and Their People, which aims to directly protect the forest by hiring forest guardians. He employs six men—three from Estado de México and three from Michoacán—to patrol the Cerro Pelón forest year round. He has found that it’s most effective to have rangers full time so they don’t resort to logging when income is suddenly gone—the butterfly season is only four months, after which the tourists (and their money) disappear. Three of Moreno’s forest guardians used to be illegal loggers. “They went from destroying the forest to provide for their family to protecting it. Now, they don’t have to risk their lives to make a living,” Moreno explained proudly. Rangers are not allowed to carry guns, so when they encounter a logger, all they can do is talk to them. Their presence alone has been incredibly effective, and—despite a lack of quantified research and statistics—those who work in the Estado de México have seen healthier forests in recent years.

For many years, scientists in the U.S. and Canada had no idea where the monarch butterflies disappeared to in the winter. After years of searching, they were “discovered” by zoologist Dr. Fred Urquhart’s team, who announced it to the world via a now famous cover of National Geographic in August 1976. While the monarchs may have been discovered by the science community, the people of the area have always known them. They called the butterflies “palomas,” or doves, before they were told their scientific name. They had no idea anyone was looking for the monarchs, since the area was largely without connection to the outside world. They didn’t know where the butterflies came from either, but from what I found, they didn’t really care about that: the monarchs arrived, and that was enough.

What they did know is that the butterflies start to show up around Día de los Muertos, or Day of the Dead, a sacred Mexican holiday in which families welcome back their deceased loved ones to celebrate their lives. While it’s celebrated all over Mexico, one of the epicenters of the celebration is in Michoacán—where the monarchs land. The Nahua, along with other Indigenous communities in Mexico, have a cyclical view of the universe, and believe that death is a necessary part of life. As the butterflies have always arrived at this time, locals believe they are the souls of their ancestors coming to visit them in another form.

María Estela Romero, a local educator and monarch tour guide with a long family lineage in Angangueo, Michoacán, told me that pre-Hispanic artifacts have been found with butterfly symbolism representing purity and fertility. “To our ancestors, [the butterfly] was a symbol of divinity,” she added, her voice warm and calm. She has worked with scientists from all over the world, and from both a scientific and cultural perspective, monarchs are a sign of life and health, an indication that the ecosystem perseveres. “Monarchs mean plans for the future, life for the future, for our next generations. The monarchs provide us with hope, with life, with work.”

I grew up on the border of El Paso, Texas and Ciudad Juárez, Mexico, where the perilous news of the border and migration is a part of everyday life. Not a day in my life has gone by without thinking about the border and without seeing the promise of making it to the other side and the tragedy of not making it. It’s no surprise that some Mexican-Americans have begun to identify with the monarchs: like the butterflies, the ancestors of these migrants defied odds, transcended borders through incomprehensible journeys, and their children are the ones that survive to keep their family lineage and stories alive.

Joel Perez, project director of the Nature Conservancy in Northwest Indiana, runs the Monarch Butterfly Festival in the Chicagoland area, a stop on the monarchs’ pathway in a predominantly Mexican-American community. The butterflies they encounter at the festival in summer will continue straight to the country of their ancestors—the place they seek for safety and warmth—and are simultaneously the grandchildren of the ones who came from Mexico, much like their human counterparts. Perez, Mexican-American himself, seeks to not only educate his community but to celebrate with them too. “It was really nice for me to be able to have this event in a community that has strong ties to each other in central Mexico…especially the older generation.” He said people are excited to share their stories about Mexico, which adds to the ancestral knowledge at the same time as people learn about how they can help the monarch butterfly. The more they learn about the monarchs, the more they learn about their heritage.

The butterflies who complete the arduous journey to Mexico and back during the fall and winter migration are dubbed the Methuselah generation, named after the longest-living person in the Bible at 969 years old. They live around eight months, which may not seem that long until you look at the lifespans of their parents and grandparents. Born in the spring and summer, the other generations survive only two to five weeks. We don’t know for sure why the Methuselah generation is capable of surviving so much longer—scientists are still studying this—but we do know that these butterflies go into diapause: a temporary state of halted reproduction. If butterflies don’t reproduce, they can live longer, and this generation is born with their hormones suppressed until they’re suddenly activated. In mid-February—starting right after what we know as Valentine’s Day—the butterflies will begin descending from the comfort and protection of the Oyamel fir tree. Suspended between air and earth, a chaotic yet delicate mating frenzy will begin. Their diapause ends just in time to mate and migrate back to Texas to lay their eggs. With their purpose fulfilled, they will die back where they were born, renewing the cycle of life.

This finely calibrated lifecycle is in danger too, as all of the usual environmental signals are changing.

“They’re getting these cues from the sun and temperature; they’re trying to move to a warmer place,” Maeckle said. “But if it continues to be warm, there’s not that much motivation to keep moving, because migration is probably the most dangerous, impossible task you could tackle as a creature like that.” She lives in San Antonio, where it was 87 degrees in November, unusually warm for the time of year. While most of the butterflies had left for their migration to Central Mexico at the end of October, some butterflies can get confused and stay if the weather is warm and the milkweed continues to bloom. This newly distorted equilibrium skews their ability to read the indicators they rely on for migration.

This poses new threats for the butterflies. Firstly, the later they leave, the less chance they have of surviving the colossal migration. Secondly, the ones who stay might move out of diapause, mate, lay eggs, and die shortly thereafter. Lastly, those who don’t leave for the fall migration—whether it be from environmental confusion from climate change or other factors—are 13 times more likely to be infected with a deadly parasite that will lead to their untimely death.

The Earth’s iron core, part liquid and part solid crystal, produces the Earth’s magnetic field by creating powerful electric currents that extend out into space. A compass works by detecting and responding to the Earth’s natural field by a magnetic, free-moving needle. In order to navigate across thousands of miles to a precise location, monarchs need to know where they are and where they want to go. As any traveler would, they need some sort of map and compass. As much as I would love to picture them strapped with a tiny fanny pack, their methods are even more fantastical than that. Scientists don’t understand their map yet, but they do know about the monarchs’ compass. These tiny insects are equipped with celestial navigation, a “time-compensated sun compass.” This basically means they use their circadian rhythm, or internal clock, to follow the sun based on the time of day and year. This circadian clock is calibrated by their brain and antenna, and like a compass, their antenna utilizes the Earth’s magnetic fields to maintain direction on cloudy days.

Other migratory creatures like certain birds learn where to go by their elders. But monarchs are several generations removed from the last generation that did this migration: their parents can’t lead them to Michoacán. The fact that a tiny insect houses this kind of expertise—knowing where they are and where they’re going—is remarkable. It’s the most highly evolved migration pattern of any known butterfly—and perhaps even of any insect. Considering most of us need Google Maps to navigate Lower Manhattan, extraordinary is an understatement.

As I witness this nearly spiritual experience, the clouds roll in and once again the forest is quiet. Even a whisper sounds like a harsh interruption to such a stillness. With the butterflies retreated back to the Oyamel fir tree, all I hear is a creeeeak from one of the trees that sways slowly from side to side under the sheer weight of the butterflies, despite there not being one lick of wind in the air. The tree appears brown with what seems like clusters of leaves magnetized to it, so many butterflies that—though one butterfly weighs less than a dollar bill—branches have been known to snap from the weight. They are again in a state of slumber, motionless until the sun shines anew, giving them the energy to take flight.

The butterflies live in this unequivocal communion with their environment minute by minute. Their time in Mexico is a time of rest—a pause. It’s part of a balance that follows an inherent pattern that cannot move forward until this part of the cycle is complete. Then and only then will they come to life, give life to their young, and pollinate the flora of three countries. Equilibrium, therefore, is essential. After all, we would not have the rapturous growth and radiant beauty of spring without death in fall.

“Monarchs mean plans for the future, life for the future, for our next generations. The monarchs provide us with hope, with life, with work.”

For 50,000 generations, humans understood ourselves as a part of nature. As journalist Michael McCarthy said on the podcast “On Being,” nature is “where we became what we are, where we learned to feel and react…where human imagination formed…where we found our metaphors and similes.” It’s scientifically proven that if a hospital patient has a window with a view of trees, they heal faster. Those of us who live in cities often seek nature in times of stress or go to the beach for vacation. “We might have left the natural world, most of us, but the natural world has not left us,” McCarthy concluded. Whether we’re aware or not, perhaps we seek it—crave it—inherently.

Most of us have left the time when we had an intimate knowledge of the animals we hunted and plants we foraged, when we followed our circadian clock and moved in unison with the rest of the planet; now, we are always on. Since the butterflies’ winter migration was discovered by Dr. Urquhart’s team in 1976, the human population has doubled. That development threatens the lives of the monarchs, and humans across North America must work to save the species. As María Estela Romero put it, “This is the cooperation of many hands: teachers, families, communities, and governments. The work to save the butterflies is like an engine. If one screw falls, the entire machine is ruined.”

All hands are on deck. But some of these efforts, however well-intentioned, have the opposite effect. Some people have planted milkweed in Mexico—where it is invasive, and not useful to the monarchs. The topic is understandably complex and paradoxical: everyone wants to help, but sometimes not doing enough research means further threats to the species we are trying to save.

On the other hand, countless scientists, organizations, and citizen science programs in all three countries have developed methods to help mitigate their respective challenges. In the U.S., people have banded together to educate and rebuild lost habitats through festivals, tagging programs, and milkweed gardens. In Mexico, there are reforestation efforts as well as locals like the Moreno family who are paving their own way to conserve their home, largely funded by the donations of visitors. A symbiosis spanning three countries, climate factors, and the livelihood of very specific flora at very specific times, this story with no beginning will hopefully have no end.

As one of the guests on our butterfly journey stared at a tree holding millions of butterflies, brows furrowed from confusion and mesmerization in witnessing such an event, she asked Moreno yearningly, “But how do they know to come here?”

“We don’t know,” he responded, gazing up. “It’s just a mystery.” And maybe that’s enough.

Music Pour Le Sport @ 11th House Agency Video editing Molly Gillis

This article first appeared in Atmos Volume 08: Rhythm with the headline “The Butterfly Effect.”

Saving the Monarch Butterfly Migration