Words by Erin Wong

Photographs by Ashish Shah

Tenzing Chogyal Sherpa grew up in a lush hillside town known as the gateway to the high Himalayas. Resting on the shoulder of a shorter peak, the stone houses of Namche Bazaar gaze upward at mountains rising several miles above sea level. The unimpeded sun glows white against their snowy peaks, which encircle the horizon like a fortress teeming with life.

As a child, Chogyal hardly recognized the singular beauty of the place he called home. It was the only place he’d ever known. He learned to climb the rhododendron trees and made his tea with water drawn from reservoirs of melting ice. In the winter, when it snowed, Chogyal remembers playing outside until his face turned red, building snowmen with his brother, and stumbling after monks as they skied expertly down the gentle slopes.

It was not until later, when he moved to Kathmandu and studied environmental science, that the threads of his life began to weave more tightly together, offering a stark portrait of how the mountains were changing before his eyes.

The glaciers of the Hindu Kush Himalaya—a mountainous territory that spans eight countries across Asia, including Nepal—could lose up to 80% of their total volume by the end of the century. According to a 2023 assessment from the International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD), glacier disappearance has already accelerated 65% faster between 2011 and 2020 than in the previous decade.

The speed of the oncoming glacier melt, not only in the Himalayas, but also in the South American Andes, the European Alps and other high-altitude regions, is transforming life for people who live in the mountains. Season by season, changing weather patterns threaten to upend their access to water, while disrupting the agriculture and tourism that underpin their economy. Many live directly below a swelling glacial lake, which can burst into floods, sweeping away entire towns.

These risks—and the rising recognition of local voices—have pushed once-hidden mountain communities into the global spotlight.

Now a cryosphere analyst at ICIMOD, Chogyal often wears multiple hats. In addition to research, he also educates people in his hometown about climate change and ways to mitigate its future impacts. As a spokesperson for ICIMOD, he shares about the growing risks that they are seeing on the world stage.

“Maybe for some people, this is just a scientific endeavor,” Chogyal said, “But for me, I feel like this is much more of a personal journey, because my hometown, my way of life, the Sherpa people—I think they’re all at risk as well.”

Protecting life in the mountains depends on keeping global temperature rise under 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels. According to research compiled by the International Cryosphere Climate Initiative, if the world reaches 2 degrees of warming, half of the ice in the Hindu Kush Himalaya will irrevocably disappear. If 2 degrees is reached, nearly all tropical glaciers in the northern Andes and Africa will be gone by the end of the century.

There is still some hope for glacier regrowth in 1.5-degree scenarios. But whether this goal is achieved or missed, more immediate disasters are starting to imperil mountain life today.

Late last year, the Swiss Academy of Sciences found that glaciers in Switzerland lost 10% of their remaining volume in the last two years alone. Over the summer, a glacial lake outburst in Sikkim, India took more than 40 lives, even after the scientific community had previously warned that the rising volumes of water posed an extraordinary risk.

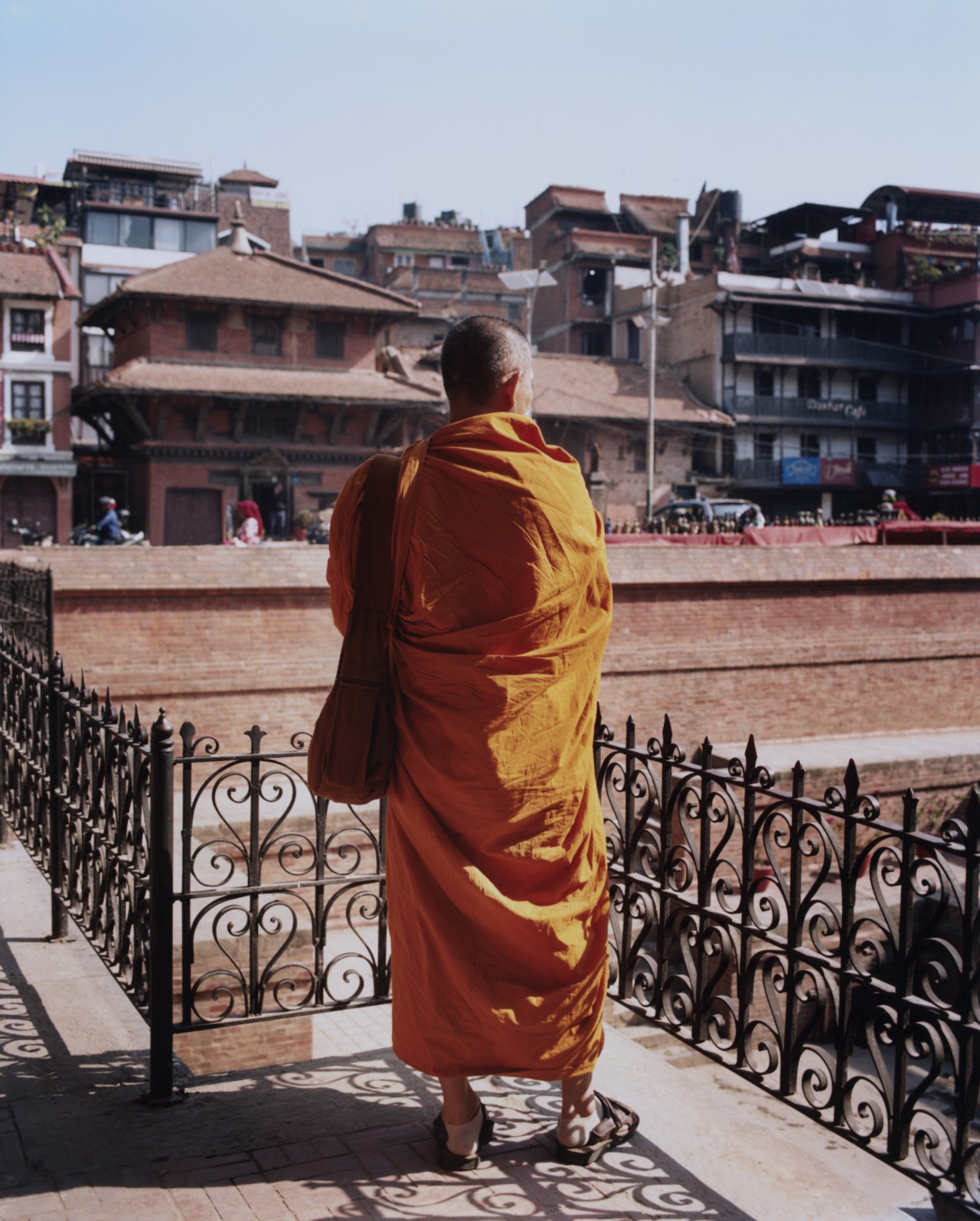

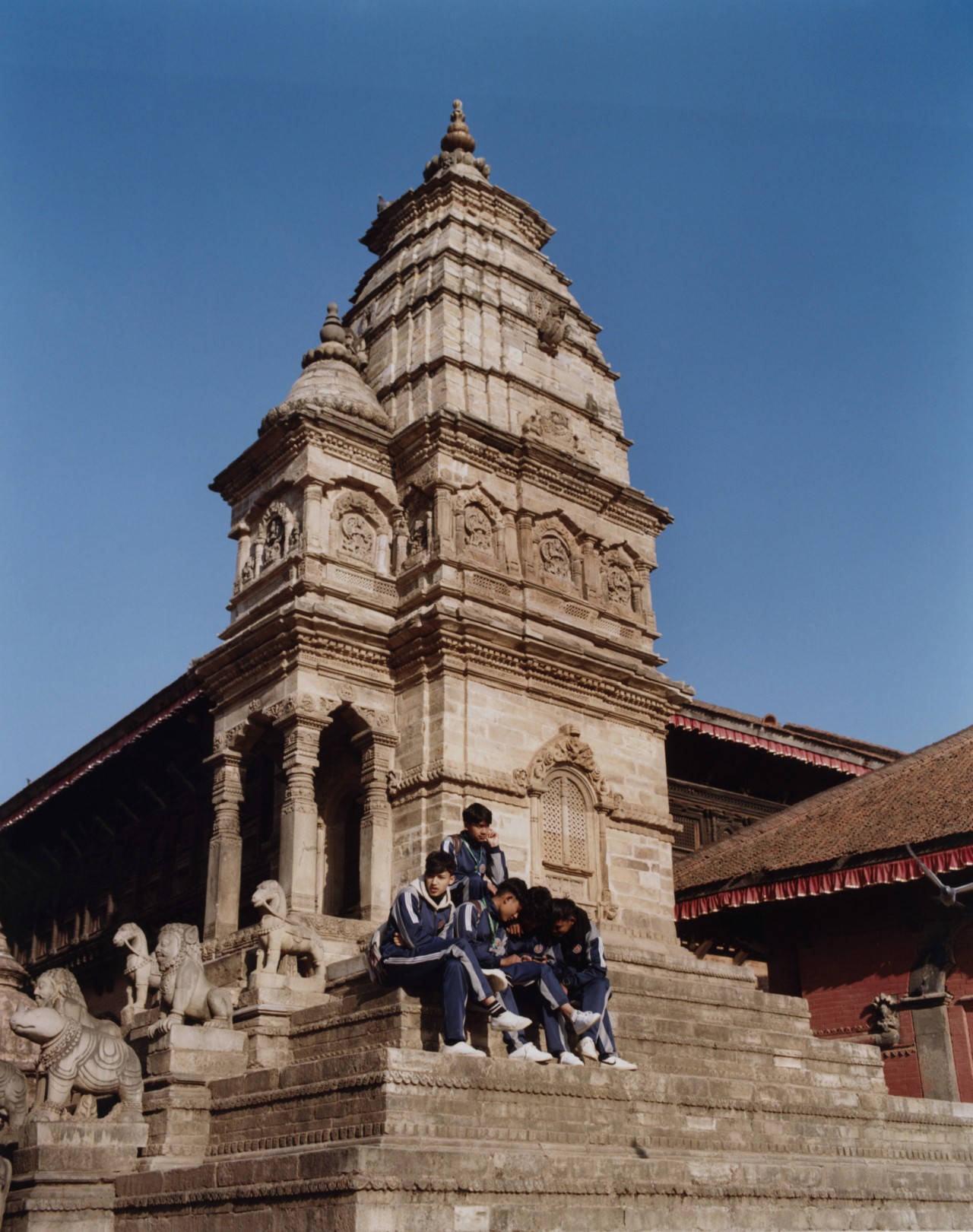

In the Khumbu region of northeast Nepal, increasing floods and unusual weather are layered on top of ongoing economic change. For centuries, the Sherpa people herded yak and traded goods along a remote network of routes between Nepal, Tibet, and India. They practiced Buddhism, blended fluidly with other Indigenous and nomadic groups, and learned to live in harmony with the steep ridges and annual snowfall. (“Sherpa” is used as a surname by some members of the Sherpa ethnic minority in Nepal. The term sherpa, with no capitalization, refers to the mountaineering profession.)

In 1953, however, Sherpas gained international esteem for their essential role in the first ascent of Mount Everest. Since then, Namche Bazaar has transformed from a remote village to a high-demand tourist destination, contributing an outsized proportion of Nepal’s GDP.

“It is like the gods are showing their displeasure through landslides and avalanches.”

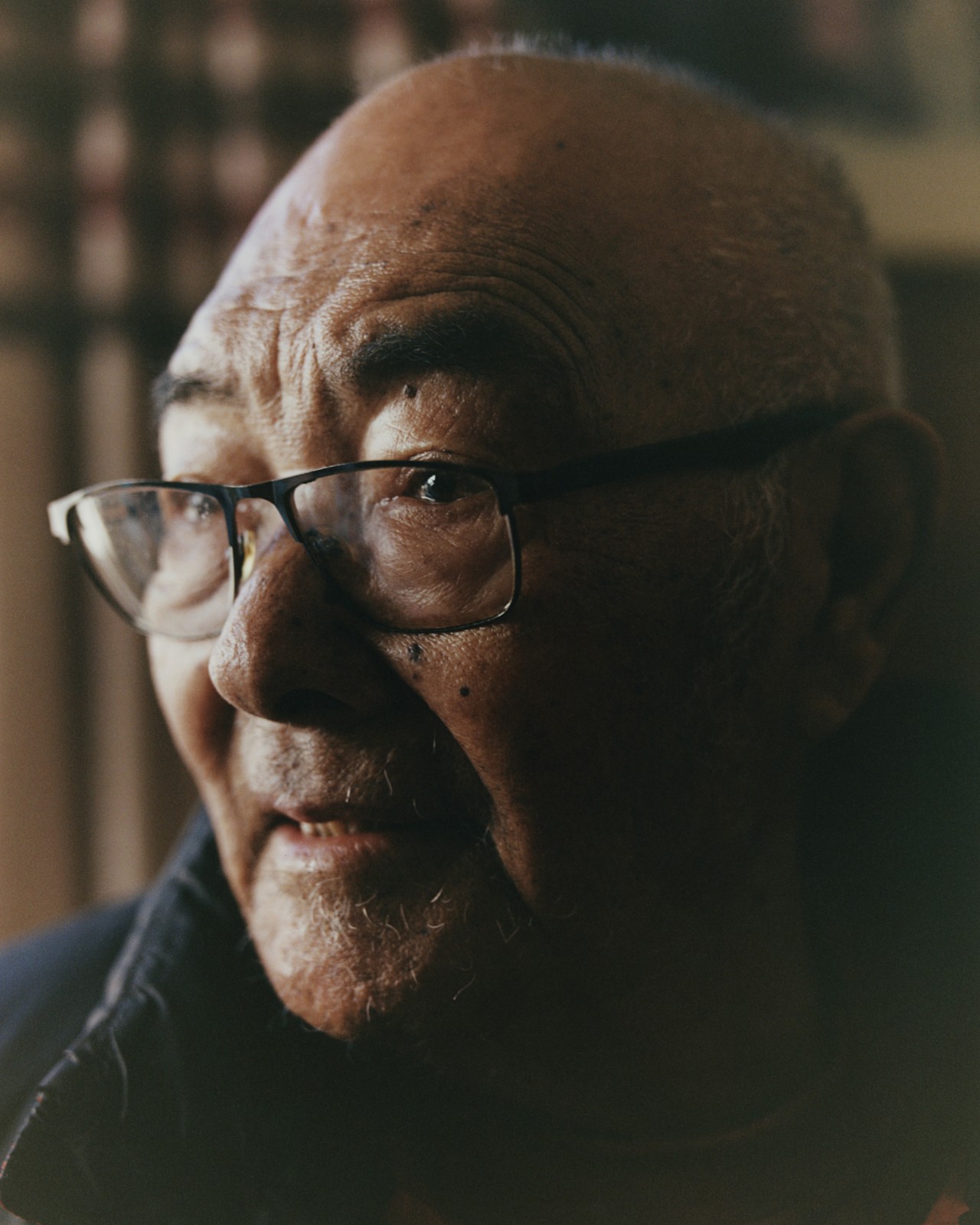

Chogyal’s grandfather, Kanchha Sherpa, is the last living member of the first ascent. Now 93 years old, Kanchha was not yet 20 when he walked four days from Namche Bazaar to Darjeeling, India, where he met Tenzing Norgay and was recruited to join his expedition. Back then, mountaineering conditions were notably more rugged and dangerous. The path was so untouched by civilization that they stripped the branches from felled trees and walked across crevasses on cylindrical logs, without the steel ladders that mountaineers use today.

Climate change has ensured that the route remains dangerous, despite technological advances in gear and infrastructure. When Kanchha looks at the mountains today, he says that the once-frequent snowy days are diminished, and the white beauty of the mountains is fading. His grandson tells him about the atmospheric conditions behind this, but Kanchha also believes that the rising accidents are the result of divine displeasure.

To Buddhist Sherpas, including Kanchha, the mountain lakes are deities, and spirits live in the glaciers and mountains. These natural landscapes are sacred, and disturbing or harming them will invite moral rebuke. When it comes to global warming, Kanchha told Atmos, “It is like the gods are showing their displeasure through landslides and avalanches.”

His grandson has learned to tie these two narratives together, embracing both Kanchha’s religion and his own faith in scientific inquiry. In a way, Chogyal said, mountain communities’ traditional beliefs are in line with science: changes in the environment are the direct result of pollution and overuse. Returning to a symbiotic relationship with the natural landscape can protect them.

In a video for ICIMOD, Chogyal told his grandfather’s story alongside his own to show how the glacial melt spans three generations of his family. “Both of us have watched the snow and ice melting rapidly in our lifetimes,” he said. “We need the world to go into emergency mode again, and act now to save our snow.”

To Chogyal’s surprise, that video played in front of nearly a dozen foreign ministers and heads of state, including French President Emmanuel Macron, at the One Planet Polar Summit in Paris in November. While the conference focused largely on the North and South Poles, Chogyal was elated to see his home, the Third Pole—the third-largest block of ice on Earth—represented on the international agenda.

What happens in the Arctic and Antarctic has tremendous implications for sea-level rise and ocean currents, Chogyal reflected to Atmos later. Yet the direct humanitarian consequences of what will happen in the Third Pole are equally vast. The glaciers of the Third Pole provide irrigation, freshwater, and cornerstones of cultural life to a quarter of the world’s population from source to sea.

Unlike small island developing states, where sea-level rise impacts the entire country, mountain communities often live in rural, less populous regions of much larger countries, like China, India, or Australia. They hold no seat at the United Nations, and they may be minorities in their own countries (Sherpas comprise roughly 1% of the Nepalese population). This relative invisibility makes it challenging for them to seek funding, pushing them to find platforms through NGOs or research networks to make their issues known.

“What we’re now seeing is this diversity of voices coming through—of experiences, of languages, of expertise, and an increased [valuing of] Indigenous and local knowledge, which is also something that was not often the case in the past,” said Carolina Adler, executive director of the Mountain Research Initiative, a coordination network for academics and scientists studying mountains.

This movement, Adler said, is reaching new landmarks all the time. The most recent Canadian Mountain Assessment combined First Nations and Inuit knowledge with modern scientific approaches. It was authored in part by Indigenous contributors, some of whom represent the 1.3 million people who live in the country’s mountains. At the Cryosphere Pavilion at COP28, the 28th Conference of Parties to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, panels also hosted speakers with direct experience of loss and damage.

Jamyang Jamtsho Wangchuk was among them. A climate activist from Bhutan, Wangchuk cycled from the capital city of Thimpu to Mount Everest and back to collect meltwater from a glacial lake. He then cycled halfway from Thimpu to COP28 in Dubai, documenting the scars of climate disasters he saw along the way, left over from the 2023 heatwaves in northern India and the 2022 floods in Pakistan. In his own country, he worries most about how the glacial retreat will affect the country’s economy, which relies on hydropower. “Without glaciers, there will be none [of that],” he said. “We’re in a very precarious position.”

In his activism, Wangchuk emphasizes the relationship between high-mountain residents and downstream communities, as well as the shared impacts across mountainous regions of the world. While the composition of their local economies and the visibility of mountain people may vary, the environmental threats remain the same.

Globally, an estimated two billion people are fully or in large part dependent on water from mountains, according to the sixth assessment report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. A 2023 study in Nature Communications also found that 15 million people worldwide are in the path of a potential glacial lake flood, with higher concentrations in Pakistan, India, China, and Peru.

Perhaps the most famous of this group is Saúl Luciano Lliuya, a Peruvian farmer and mountain guide whose family lives below the glacial lake of Palcacocha. In 2015, he filed a lawsuit against the German energy company RWE for its contributions to climate change, arguing that it should help pay for adaptation measures to avoid a future flood. The landmark case will continue in Hamm, Germany this year. Over the past eight years, Lliuya has become an icon in climate advocacy, as a mountain resident who has chosen to fight for the future of his home.

It’s a story that Chogyal can relate to. In 1985, his mother, Nima Doma Sherpa, went into the mountains to gather firewood with her sister, when a major glacial lake outburst destroyed 14 bridges, 30 houses and a hydropower dam, blocking their way home. They slept outside for two days while their relatives built another bridge from a felled tree, like the ones Nima Doma’s father-in-law once crossed, so the sisters could return. The two still recall eating spoiled potatoes as children, because the outburst destroyed any means of traveling for more food.

It was one of the first major incidents for Nepal, after which the country began to invest in glacial lake monitoring and early warning systems. Villagers have since developed ad hoc WhatsApp groups to communicate any upstream floods to others in harm’s way. In the years since, the national government and UN Development Program have experimented with glacial lake outburst mitigation, including the construction of concrete walls at the edge of one lake, to control the water flow.

“That might not completely eliminate the hazard aspect,” Chogyal said, “There is still risk. But what it did is give hope to the people; the people living downstream can now sleep a little bit better.” And with this small bit of hope, he continued, other residents of the Everest region are motivated to take action themselves, building dam reinforcements and digging deeper channels to lower pressure on the glacial dams.

Further north in the Himalayas, engineers in Ladakh are building artificial glaciers—ice stupas—to combat water scarcity in the dry spring. In Namche Bazaar, Chogyal’s own dream is to develop a citizen science initiative that employs mountain residents in data collection and the implementation of mitigation and adaptation measures. With a little funding, this model could reduce the need for scientists to travel to remote regions, while drawing on the inherent expertise of mountain communities to strengthen climate solutions. It’s a dream that Kanchha fully supports, and he is proud that his grandson has something unique to offer the village to help them adapt.

“Mountain people are already [doing] quite well at that,” Chogyal said. “They respect how nature can change.”

PHOTOGRAPHY ASSISTANT Anish Oommmen SPECIAL THANKS Annie Dare and ICIMOD

This story first appeared in Atmos Volume 9: Kinship with the headline “The Voice From the Mountains.”

The Line of Sherpas Saving Lives and Glaciers in the Himalayas