Words by Scarlett Harris

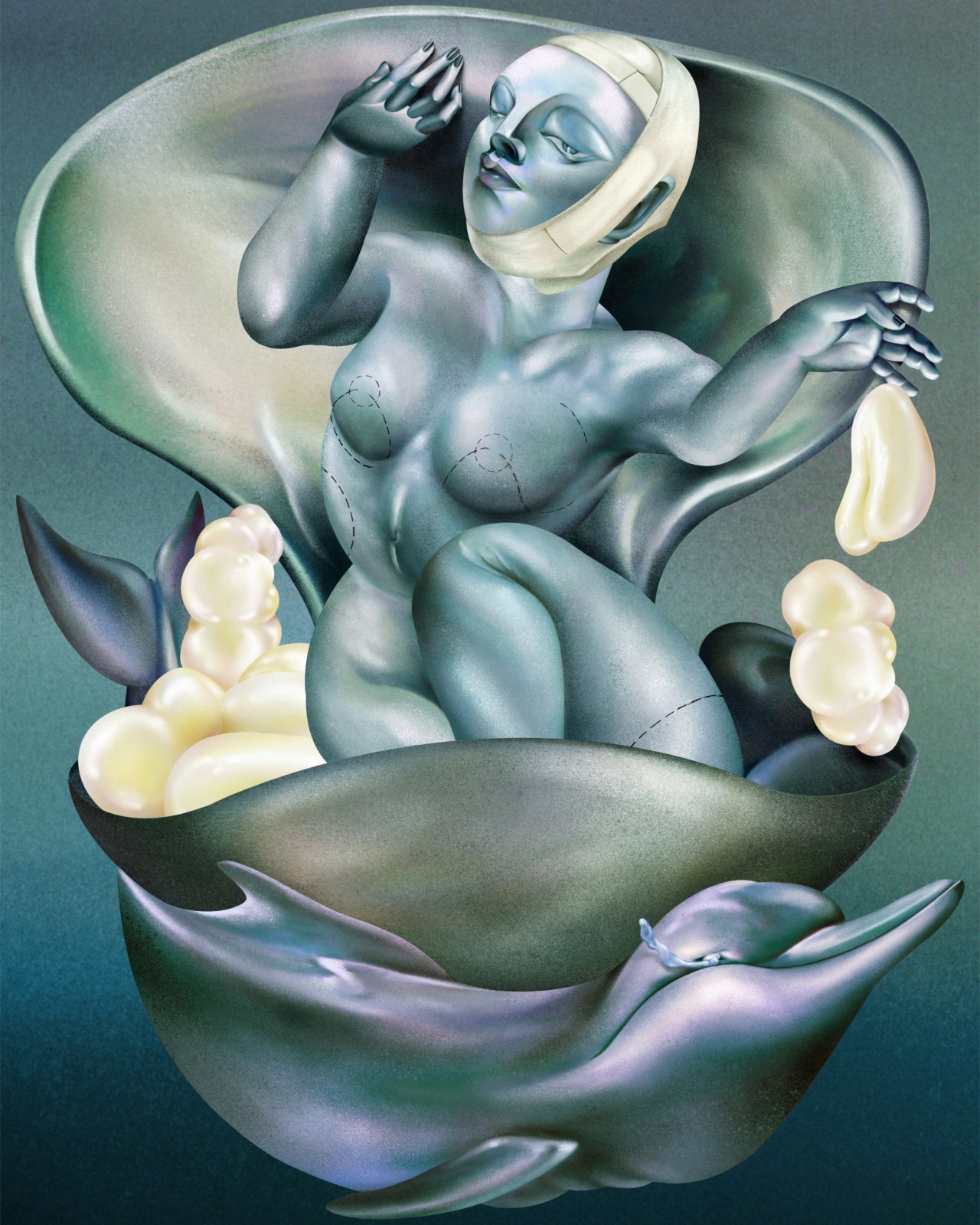

artwork by lulu lin

“445 cc, moderate profile, half under the muscle!!! Silicone!!! Garth Fisher!!! Hope this helps lol.”

These words rang across the internet on a casual Tuesday in June, after a TikTok user asked Kylie Jenner to share the details of her breast augmentation. To the surprise of many, Jenner obliged, confirming the long-rumored procedure and sending social media into a frenzy by listing the exact specifications of her implants. Her candor reflects a broader societal shift: the “democratization” of cosmetic surgery, a trend the Kardashian-Jenners—and influencer culture at large—have helped drive.

Plastic surgery and FaceTune are today so widespread that The New Yorker has officially declared the era of “Instagram face.” Once a taboo—or at the very least a pipe dream—cosmetic surgery has now been normalized to the point where dissecting celebrity aesthetics is practically a pastime, with a host of Instagram accounts dedicated to before-and-after transformations that collectively draw millions of followers. Hundreds of thousands of videos showing rhinoplasties and tummy tucks have also been uploaded to TikTok, garnering millions of views.

Some argue that celebrities being transparent about the lengths they go to achieve their looks, rather than repeating the tired “water and sunscreen” lie, is progress. That transparency helps reduce stigma around cosmetic interventions that, for many, are tied to survival and dignity: reconstructive care for trans individuals; responses to racism, ageism, and workplace discrimination; or recovery from illness. But it also raises harder questions. What does it mean when non-essential, elective procedures—resource-intensive and shaped by inequities of race, gender, class, and access—are increasingly framed as standard, even aspirational, care?

And inequity isn’t the only issue. The industry also carries a heavy environmental cost. Health care accounts for 4.4% of global carbon emissions, enough to rank fifth worldwide if it were a country. Surgery is among its most resource-intensive practices, generating around 70% of incinerated medical waste and 30% of solid hospital waste, from discarded latex gloves to internal medical devices such as pacemakers and artificial joints. In the United States alone, the CDC estimates there are 51.4 million inpatient surgeries each year. Of these, the International Society of Aesthetic Plastic Surgery reports that over 6 million were aesthetic procedures in 2023—about 12% of the total. Many operations in this category serve clear and necessary medical and psychological needs, from reconstruction after cancer or injury to the correction of birth defects to gender-affirming care. These procedures are, quite simply, essential.

“What does it mean when non-essential, elective procedures—resource-intensive and shaped by inequities of race, gender, class, and access—are increasingly framed as standard, even aspirational, care?”

Cosmetic surgery, meanwhile, has grown into its own rapidly expanding market. Currently valued between $59.13 billion and $85.83 billion, the sector is projected to reach $160.47 billion by 2034. The scale of the market hints at the scale of its footprint. In 2020 alone, rhinoplasties in the United States produced an estimated 6 million kilograms of carbon dioxide, the equivalent of nearly 6,000 cross-country car trips from Los Angeles to Boston. Globally, that number climbs even higher, with roughly 2.5 million additional rhinoplasties performed in the same year.

Breast augmentation remains the most popular plastic surgery, and most implants are made of silicone. Despite industry claims of sustainability—somewhat justified, since the rubber-like material generates less medical waste than many single-use plastics—silicone is still derived from fossil fuels and manufactured through an energy-intensive heating process. It does not biodegrade, and while technically recyclable, it requires specialized services not available to most people. Certain silicones and additives also carry health risks, leaching into the environment and, in some cases, even our bodies.

Add to that the rise of cosmetic tourism, with patients flying to countries like Mexico, Singapore, and Turkey for breast enhancements, cosmetic dentistry, and hair transplants. In the U.S. and other countries where health care and medical insurance is becoming untenable, it’s no wonder people are traveling to circumvent these access gaps. So much so that Vogue recently published an article on the emergence of cosmetic tourism brokers to aid in this process.

Not everyone chooses—or has the means—to go under the knife. “These invasive and non-invasive procedures set a standard that people not in the same tax bracket as the celebrities and influencers getting [cosmetic procedures] can meet through products,” beauty culture commentator and Guardian columnist Jessica DeFino told Atmos. “That, in itself, creates a whole lot of waste that we wouldn’t necessarily associate with the plastic surgery or injectables industries.” In effect, surgery becomes a style that filters down through consumer products.

“There are so many more pieces to this besides the direct waste of one procedure,” she added, pointing to Kim Kardashian’s shapewear brand Skims’ viral new headwrap as one example. The product mimics the “post-op aesthetic” of cosmetic surgery and claims to firm the skin, but experts are skeptical. DeFino argues it reflects a broader pattern: disposable beauty items like lip tape and under-eye patches that, as she puts it, mean you’re “basically removing garbage off your face and body every morning.”

“These invasive and non-invasive procedures set a standard that people not in the same tax bracket as celebrities and influencers can meet through products. That, in itself, creates a whole lot of waste.”

Beyond consumer culture, questions of ethics are shaping the industry, too. Most injectables have undergone animal testing at some stage, as mandated by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, though Health Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. has promised to end that, raising the possibility of cruelty-free fillers in the future. Meanwhile, the “clean beauty” craze echoes MAHA’s themes of what counts as “natural” and who decides: influencers now tout snail mucin and even salmon sperm as skincare ingredients, despite their dubious sourcing.

New techniques are emerging as alternatives. Animals can’t consent to donating their byproducts, but humans can. Enter fat transfer. Also known as autologous fat grafting, it involves liposuctioning fat from one part of the body and re-injecting it into another, say from the stomach or breast. The field is advancing into cadaver fat transfer too—using fat from the deceased as a “natural” alternative to implants or Brazilian butt lifts. While not without its own surgical footprint, these techniques at least sidestep the plastics and energy-intensive production tied to silicone and animal-derived products.

Could autologous or cadaver fat grafting also help reduce the sector’s reliance on single-use plastics? Perhaps—but only marginally. The carbon cost remains, along with the emissions from traveling to the clinics pioneering these procedures, many of them outside the U.S. as the National Institutes of Health scales back research funding.

There is enormous room for improvement in other areas, too. Operating theaters are among the most energy-hungry spaces in health care, with heating, ventilation, and air conditioning systems running at full tilt around the clock. Yet cleaner energy sources and efficiency upgrades are already available. Research also shows that recovery systems for anesthetic gases—many of which are released unmetabolized into the atmosphere as potent greenhouse pollutants—could sharply reduce emissions if widely adopted. These technologies exist; what’s missing is industry commitment and regulatory pressure to scale them.

For many, these procedures can change lives in ways that feel deeply personal and liberating. For others, the normalization creates yet another impossible standard to measure up to; an expensive marker of inequality rather than empowerment. But the environmental costs do not belong to patients; they fall to a health care sector that already has the tools to reduce its footprint. Technologies for cleaner energy, waste reduction, and emissions recovery already exist. What’s missing is the commitment—and regulation—to normalize them, too.

The Hidden Cost of The Cosmetic Surgery Boom: Medical Waste