WORDS BY JASON P. DINH

photographs by lyndon french

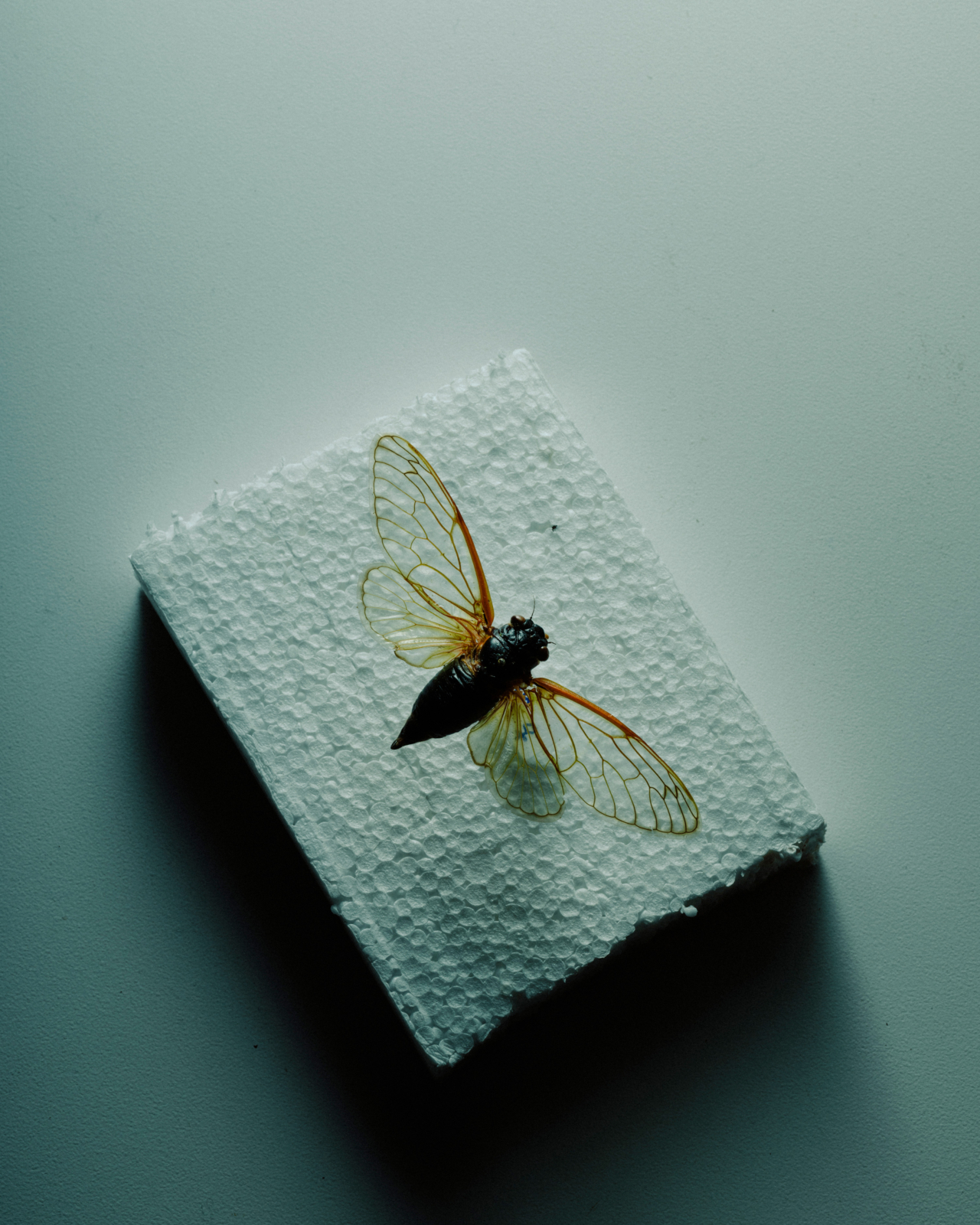

In the summer of 2004, I turned my house into something like a cicada festival. Jars lined our windowsills, brimming with molted exoskeletons. Live insects lumbered across the landscapes I staged in aquarium tanks. With each bug I plucked off a tree and placed on my arm for safekeeping, a sensation rippled through my body—the tickle of their tarsi with each step, but also the thrill of witnessing a biological marvel. For eight-year-old me, impressionable and curious, there was profound truth in the cicadas’ scientific name: Magicicada.

I grew up in Maryland, where Baltimore’s suburbs and sticks begin to blur. It was ground zero for the Brood X cicada emergence. You couldn’t get anywhere that summer without being pelted by the insects—my first time witnessing such a spectacle. Their screeches rent the air, their bodies plastered plants and patios.

Across the eastern half of the U.S., there are 15 periodical cicada broods. Twelve of them emerge every 17 years, and the other three emerge every 13. They spend over 99% of their lives underground as nymphs, sipping xylem from plant roots and biding their time. But in late spring nearly every year, one or two broods awaken, mature, and overtake their range as billions to trillions of individuals perform an ear-splitting mating ritual for two months before dying, the soil freckled with their carcasses, their bloodline waiting over a decade to emerge once more.

It’s understandable that some folks see this as a nuisance. Cicadas are the world’s loudest insects; a tree covered in them can be deafening. But as a kid, they were pure joy. I would pull them off the tree in my front yard, seeing how many I could fit on my arm at once. I watched with wonder as they emerged from their juvenile skins, inflating and hardening their bodies into adult form. I hounded teachers, librarians, and parents with all sorts of questions, the type kids love to ask: Where have the cicadas been for 17 years? How can something so small get so loud? And what’s the deal with the prime numbers?

Now, as I reflect two decades later, I realize that these are the types of questions I continue to ask as a scientist and science writer.

During my Ph.D., I figured out how and why crustaceans called snapping shrimp vaporize water, producing sound, light, and heat nearly equal to the surface of the sun. As a science journalist, I’ve covered discoveries like dung beetles which navigate using the Milky Way and fish which brandish neon-colored jaws during fights. My work has been rooted in an insatiable curiosity for nature, with a bent toward the overlooked, cast-aside corners of the world. That worldview emerged alongside the Brood X cicadas in 2004.

In a way, those cicadas opened a door that was not obviously available to me. Naturalists often credit formative early travel for seeding their love of Earth. Not me. Growing up as a child of two Vietnam War refugees, I didn’t have the luxury of visiting the planet’s natural wonders like National Parks or biodiversity hotspots. But in 2004, cicadas brought one of those wonders to me, screeching in my front yard, begging me to stop, notice, and admire the world beneath my feet. As this year’s historic cicada emergence presses on, I wonder how many kids are having that experience now.

This spring, for the first time in 221 years, Broods XIX and XIII are emerging at the same time—and to much fanfare. Dual emergences aren’t uncommon, but this particular pairing is special because the broods border each other and might even overlap in a small part of central Illinois. It’s a syzygy—not of celestial bodies, but of life cycles. The moment is ripe to foster curiosity, and scientists are capitalizing.

Learning to see beauty in your own backyard expands who has the opportunity to fall in love with nature.

Gene Kritsky, an entomologist at Mount St. Joseph University and author of the book on this year’s emergence, A Tale of Two Broods, compared it to last month’s total solar eclipse. People are planning vacations to see the spectacle. He and his wife will be there themselves, coordinating citizen science projects for iNaturalist and for his own app, Cicada Safari. He’ll be lecturing and doing outreach to stoke excitement. “Periodical cicadas are the gateway drug to natural history,” Kritsky told me. And once you overcome the nuisance, they are remarkable.

American periodical cicadas emerge in prime numbers, but scientists are puzzled by why (one leading theory posits that it minimizes hybridization; another says it’s to prevent predators from synchronizing to their life cycles). They seem to tally the years based their host plant’s seasonal cycles, but nobody knows exactly how. And their unusual cadences cause momentous shifts in nutrients, cascading to affect trees, soil, insects, birds, snakes, mammals, and more.

Despite being the size of a thumb, a single cicada can reach 100 decibels from a meter away—about as loud as a jackhammer from the same distance—and they produce sound in an unusual way. Unlike most insects, like crickets, which sing by rubbing body parts against each other, cicadas buckle a ribbed membrane called a tymbal, a mechanism similar to stretching a bendy straw. That structure is attached to a resonating air sac that amplifies and tunes their song.

And, in one of my favorite discoveries of 2024, researchers just reported that cicadas are record-setting urinators, too. Unlike small insects, which pee in droplets, cicadas pee in jets like we do, the smallest animals known to do so. Clocking in at three meters per second, their urine streams are the fastest ever measured—over three times faster than humans.

Saad Bhamla, an engineering professor at the Georgia Institute of Technology who made the discovery, said this research could one day inspire new jetting systems for miniature nozzles and robots, but that’s not his main motivation. Frankly, he says, “I don’t care.”

He does this because it makes him happy, it makes kids happy, and it ignites curiosity. To him, it’s about lighting a fire—cultivating a mindset that seeks out discovery, even in what appears to be an unremarkable bug in one’s own backyard. “That’s much more powerful and life changing” than the engineering applications, he told me.

Cicadas once taught me to marvel at the wildlife beneath my feet, drawing my gaze to the ground, to the unseen and unappreciated.

He’s seen that mental shift in his four-year-old son, he beamed as he told me. The boy loves cicadas, Bhamla said, so much so that his teachers have requested parental intervention to stop him from bringing them into their classroom. “Kindergarten teachers hate me,” Bhamla joked.

I see myself in his story, and I know firsthand that childhood backyard naturalism matters, both at individual and societal levels.

Learning to see beauty in your own backyard expands who has the opportunity to fall in love with nature. It’s a radical mental shift that bucks historical precedent.

For as long as the concept has been around, “The Great Outdoors” have been weaponized and gatekept to uphold white supremacy, colonialism, and class divisions. Even today, 94.5% of visitors to national forests are white, and racial minorities can’t even go birding or hiking without fear of retaliation. It’s no coincidence that roughly 70% of environmental science degree-earners in the U.S. are white, as are 84% of environmental journalists.

Democratizing a love for nature would radically diversify the environmental movement and workforce. That requires broadening access to outdoor leisure, but another avenue to get there is by opening our hearts to the wildlife in our own backyards—fostering spaces for discovery where everyone can access it. Perhaps no creature is better suited to do that than Magicicada.

Cicadas once taught me to marvel at the wildlife beneath my feet, drawing my gaze to the ground, to the unseen and unappreciated. Their emergences welcome folks from all walks of life to witness one of Earth’s greatest evolutionary feats. So, as what some have called a “cicadapocalypse” commences this month, maybe we should embrace it. Maybe we should marvel rather than malign. Maybe we should heed Bhamla’s advice from his TED Talk last year:

“We can discover marvelous in the mundane, even in our own backyards. We just have to look closely.”

Thanks, Cicadas, for Democratizing a Love of Nature