Photograph by Frederic Lewis / Archive Photos / Getty Images

WORDS BY GREGORY D. LARSEN

Dr. Gregory D. Larsen was a biologist with the National Park Service. This Points of View article reflects his opinions, not necessarily those of Atmos.

Five months ago, I packed my bags, loaded my truck, and trekked nearly 4,000 miles across the country from North Carolina to Juneau, Alaska. The move cost me thousands of dollars and meant leaving behind the life I had built on the East Coast—but I knew it would be worth it. After 18 years in wildlife biology, I finally landed my dream job as a biologist with the National Park Service.

It was a permanent, competitive position and everything I hoped for. I was leading programs to monitor sea otters, seals, and seabirds in some of the nation’s most spectacular ecosystems. It ended suddenly on February 14, when I and thousands of other probationary employees were terminated without cause in what some have called the “Valentine’s Day massacre.” Now, I’m unemployed and thousands of miles away from all of my family, the bulk of my friends, and much of my professional network.

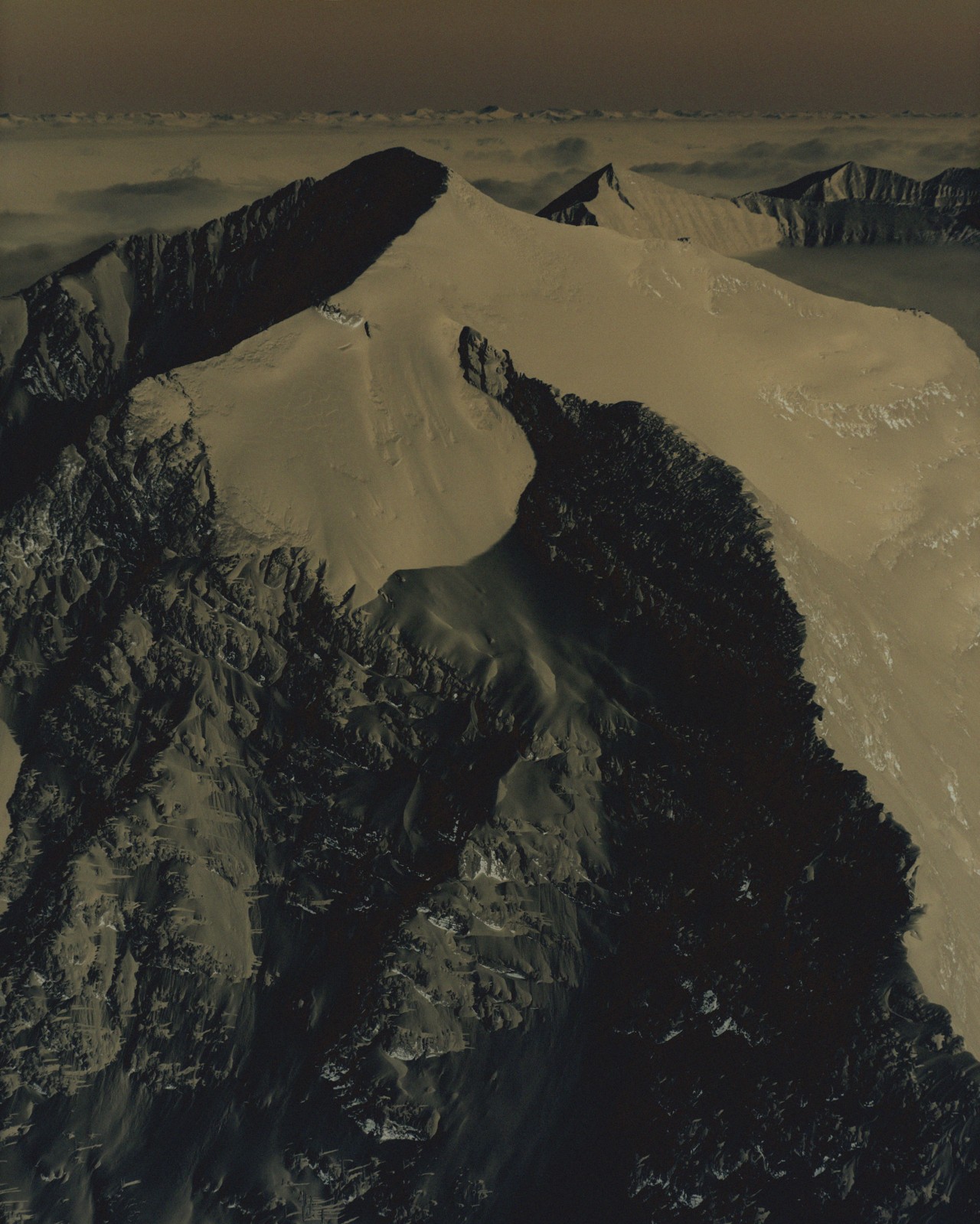

Before I was terminated, I worked at the Southeast Alaska Inventory and Monitoring Network. We collected, analyzed, and shared data on the ecosystems and physical environments across four parks: Glacier Bay, Klondike, Sitka, and Wrangell-St. Elias.

The wildlife and environmental features that SEAN tracks are the lifeblood and vital signs of a national park, described in each park’s “enabling legislation” and serving as the main attractions for many visitors. It is NPS’s legal obligation to study and preserve them. SEAN’s government-mandated work is critical to NPS’s mission: to “[preserve] unimpaired the natural and cultural resources and values of the National Park System for the enjoyment, education, and inspiration of this and future generations.”

My job was to use cutting-edge technology to make SEAN’s work more efficient, integrating drones and artificial intelligence into our wildlife-monitoring process. It was a role for which I was uniquely qualified, as a drone pilot and spatial data expert with a Ph.D. in marine science and five years of experience in AI systems. Integrating these technological advancements would have allowed us to collect, analyze, and share data with greater speed and accuracy at a lower cost. It’s a bitter irony that my job—one of technological efficiency—was terminated under the guise of “government efficiency” by a tech mogul and AI evangelist.

“The effect on visitors has been instant, but the damage to ecosystems from cuts to park science will be a slow burn that could smolder across decades.”

Like thousands of other former federal employees, I was terminated without warning, without reason, and without dignity. I have friends now unemployed with young children and dismissed colleagues with surgeries planned in the coming weeks. My supervisor was notified of my termination two hours before I received a vague and impersonal email claiming that I “failed to demonstrate fitness or qualifications for continued employment.” As I went through the protocols of leaving my job, my supervisor promised me an honest performance evaluation. I don’t know whether it will help me claim any form of justice, but her words bring me some peace: I did, in fact, carry out my mission-critical, government-mandated duties with excellence.

The purge of my NPS colleagues is already felt across the country; that will only worsen as we enter the summer peak season. During Valentine’s Day weekend, the wait time to enter Arizona’s Grand Canyon National Park was twice as long as usual after the four employees who worked the primary entrance were dismissed, according to the Washington Post. Those trips will be more dangerous for visitors, too. One now-terminated park ranger was the only emergency medical technician at Devils Postpile National Monument in California and told the Independent that emergency response time at the park could now be up to three hours. The effect on visitors has been instant, but the damage to ecosystems from cuts to park science will be a slow burn that could smolder across decades.

The wildlife populations I studied in southeast Alaska, for example, are experiencing fast changes—but it’s not always obvious without the perspective of long-term records. Sea otter numbers are now near a historic high in Glacier Bay National Park since being reintroduced 30 years ago; but harbor seals and Kittlitz’s murrelets are declining, both threatened by the loss of tidewater glaciers. The consequences of shrinking glaciers ripple through the park’s ecosystem and environment, sometimes over decades and sometimes over months. It takes time to understand those impacts.

Without park science, NPS management won’t have the data needed to make informed decisions about how to protect and share the park with visitors; other agencies lose a critical source of information on threatened and protected species; and visitors experience parks with old or incorrect context and uninformed safeguards, potentially stressing wildlife and damaging the unique environments tourists traveled so far to appreciate.

“I hope I can continue my work elsewhere and that the public stands up for the systems and spaces that they value.”

More broadly, the exodus of federal workers across government agencies will devastate our ability to protect natural spaces and their communities at the time when we need it most. As peak wildfire season approaches, former USFS employees have warned that the United States will be more prone to wildfires, like the ones that ravaged Los Angeles last month. Former FEMA employees fear that people across the country won’t be able to properly prepare for and rebuild after climate disasters, which themselves will grow more frequent and intense without coordinated federal and international monitoring and action. Offices of every agency will reckon with their immediate loss of talent and the long-term loss of trust in federal employment—and the public will feel the absence of the services these offices once provided.

It’s been almost two weeks since I was dismissed from my job, and it is certainly taking a toll. My sleep and health have suffered, and with Juneau’s high cost of living, I’m unsure how long I can pay for food and rent. The cruelty of this situation is intentional and premeditated: Director of the Office of Management and Budget Russell Vought said in 2023 that he “want[s] the bureaucrats to be traumatically affected… to not want to go to work because they are increasingly viewed as the villains.” It is inhumane.

I see encouraging signs of resistance, as a smattering of individuals and organizations take steps to challenge the escalating attacks on our civil rights and institutions. Time will tell whether continued pressure will be enough to recover the offices, efforts, and safeguards that have been so quickly dismantled.

I don’t know what I will do next. I’ll fight, where I can, to protect our natural spaces, but first I’ll have to address my immediate needs. I hope I can continue my work elsewhere and that the public stands up for the systems and spaces that they value. It’s the least we can do to slow this irreversible damage to our parks and our planet.

Correction,

February 26, 2025 7:59 am

ET

The story has been updated to clarify the circumstances of sea otter repopulation in Glacier Bay National Park. They were reintroduced to the Park 30 years ago, rather than first introduced.

Terminated Parks Employee Warns of the Danger and Cruelty of Job Cuts