WORDS BY MATTHA BUSBY

photographs by bodhi shola

Twenty strangers and I gathered, holding chocolates containing a quarter gram of dried psilocybin mushrooms, a mild dose. “We’re going to take them together in a few minutes,” said Javiera Kostner, our leader for the day, as we stood in a circle on a dusty trailhead.

Our “hikrodose”—a portmanteau of hike and microdose—would take place in Santa Cruz, California, where, in January 2020, the city council decriminalized psilocybin consumption, effectively sanctioning psychedelic mushroom-powered forest walks. Since then, several hikrodosing groups have popped up on the West Coast like this one, which was organized by Kostner and her group, Magic Hikes.

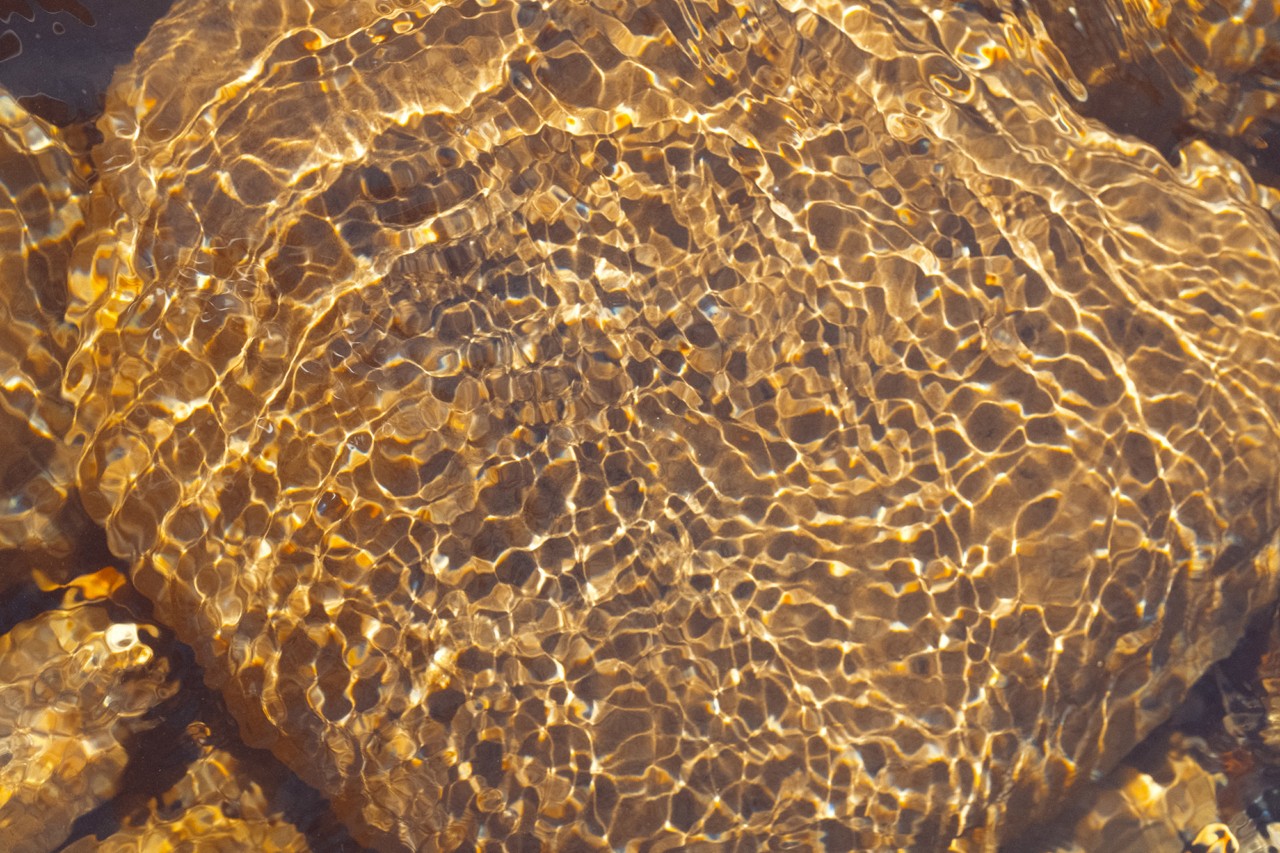

Some of us microdosed before we arrived mid-afternoon, and Kostner asked us all to signal a “medicine check-in” with our fingers to indicate how high we were from one to five. I was a two. I was extremely present, and errant thoughts were few and far between—beyond reflections on the early signs of fall around me. I wasn’t tripping, per se, but I was more attuned to the gold-colored environment and the crunchy brown oak leaves around me on the 79-degree day. I also felt more tapped into the subtle energies of the quirky group of psychedelics enthusiasts, which were occasionally unnerving but at other points profoundly reassuring.

We were all there for different reasons. One male attendee came to “anchor some light into [his] heart and into Mother Earth.” One woman was there to “connect with community.” Slightly creepily, another man expressed his disappointment that the group was relatively large because it lessened his chance of deeply connecting with every person.

After introductions and establishing ground rules, we set off. But not before those who hadn’t yet taken their dose had the opportunity to do so. “I always hold my medicine for just a moment,” said Kostner, who co-runs the Santa Cruz Psychedelic Society, “and I whisper my intention.” Members of the group held their mushroom chocolates to their hearts, gently said their prayers and mantras, and the five-mile hike around the Pogonip Open Space Reserve solemnly began.

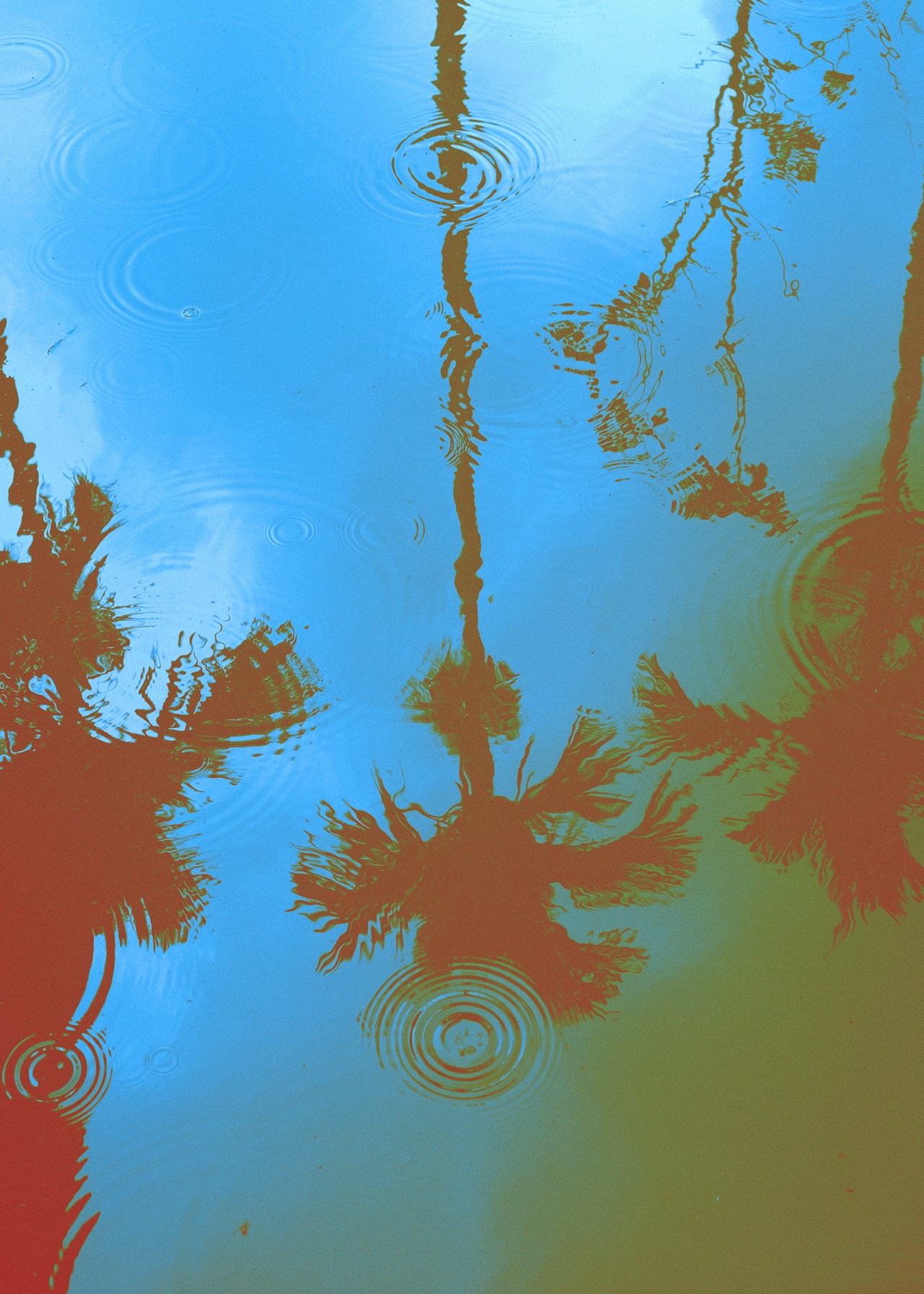

Early research suggests that psychedelics can boost feelings of empathy and connectedness to nature—potentially even prompting users to attribute consciousness to more-than-human life—especially when used outdoors. “Nature-based settings may offer a number of benefits to psychedelic users, as they can be mentally soothing, elicit reflective and mindful states, and promote experiences of awe, wonder, and connection with nature,” said Dr. Sam Gandy, an ecologist and independent researcher who has studied psychedelics and nature connectedness.

Mushroom-infused hikes have gotten a bad rap lately, seemingly because they are often not properly organized to mitigate the risks. Four male hikers in their 20s called for help earlier this month in New York’s Slide Mountain Wilderness after suffering a “debilitating psychedelic mushroom high,” according to police, with one of the group unable to walk or talk, and another losing the car keys.

The debacle followed another widely-reported fiasco in May when a pair of hikers on Cascade Mountain in New York reported that the third member of their group had died. It soon transpired that there was no death, but the hikers “were in an altered mental state,” according to the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation.

I hoped there would be no such mishaps at our more regimented and measured affair.

It wouldn’t be a steep trek. The biggest potential issue, Kostner warned, was poison oak. “Post-it notes?” asked one male attendee, whose mishearing prompted laughter from the rest of us. Poison oak is a leafy shrub that can cause serious rashes, Kustner explained, especially for women who might crouch down to use “nature’s restroom” and expose their modesty to the weeds. “If you don’t know how to recognize it,” she said, “come and talk to me.”

As we ascended a gentle incline surrounded by lush green banks of moss and English ivy, hikrodoser Gigi, who is in her 60s, told me that psychedelics saved her life following a chaotic spell of county jail stays over misdemeanors. “I was really bad with cocaine, vodka, and prostitution,” she said, withholding her surname for privacy. “I had a lot of damage from being sexually abused as a kid. I went to jail so many times.”

Then, in 2012, she drank the Amazonian psychedelic ayahuasca in Seattle on the recommendation of a friend. “The [ayahuasca] just made this path for me,” said Gigi, who returned to the merchant navy after the positive trips. Hikrodoses like today, she added, help her get further “aligned”.

People have likely consumed natural psychedelic plants and walked in nature since time immemorial. Ayahuasca is an intense traditional medicine that invites a connection to nature for many South American Indigenous groups. It should be noted, however, that some Indigenous groups rightly protect their ancestral medicine from the outside world, and non-Indigenous ayahuasca retreaters have been accused of “wanton commodification and fetishization” of Indigenous cultures.

“These rituals connect us all through time,” said hikrodoser Ben, a computer software engineer, as we passed a set of towering redwood trees, the sweet smell of cedarwood delightfully perfuming the air. “Psychedelics remind us that we are an inseparable part of nature.”

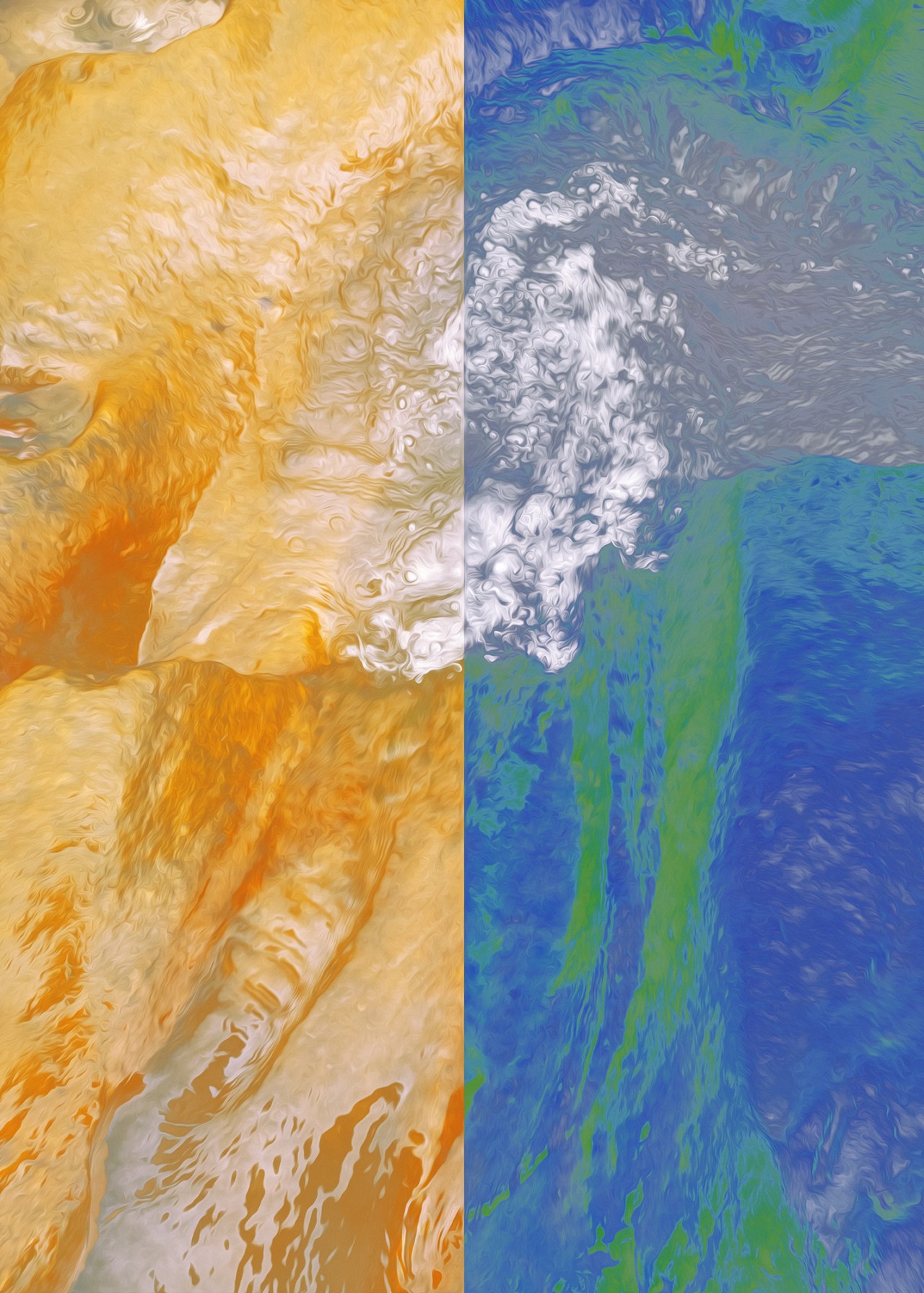

Halfway through the hike, Kostner invited us to gather by an open field, where a coyote lurked and two hawks circled, searching for mice. “We are giving the plants CO2 and receiving oxygen,” Kostner reminded us. The mention of carbon dioxide brought my mind to climate change. Much has been made about the potential of psychedelics to spur climate action, to mixed reception. Hikrodoser Tracey, for one, sees the appeal. “I really feel that if we could collectively do more events like this, it’s going to be good during these times,” she said.

Equally, the world seems to be in need of more quiet reflection rather than constant conversations, which today have spanned light language, a bizarre form of communication in tongues which speakers claim to channel from aliens; evil shamans who profess to practice black magic; and whether trees can talk. So for the final stretch of the hike, Kostner declared, we are to be silent.

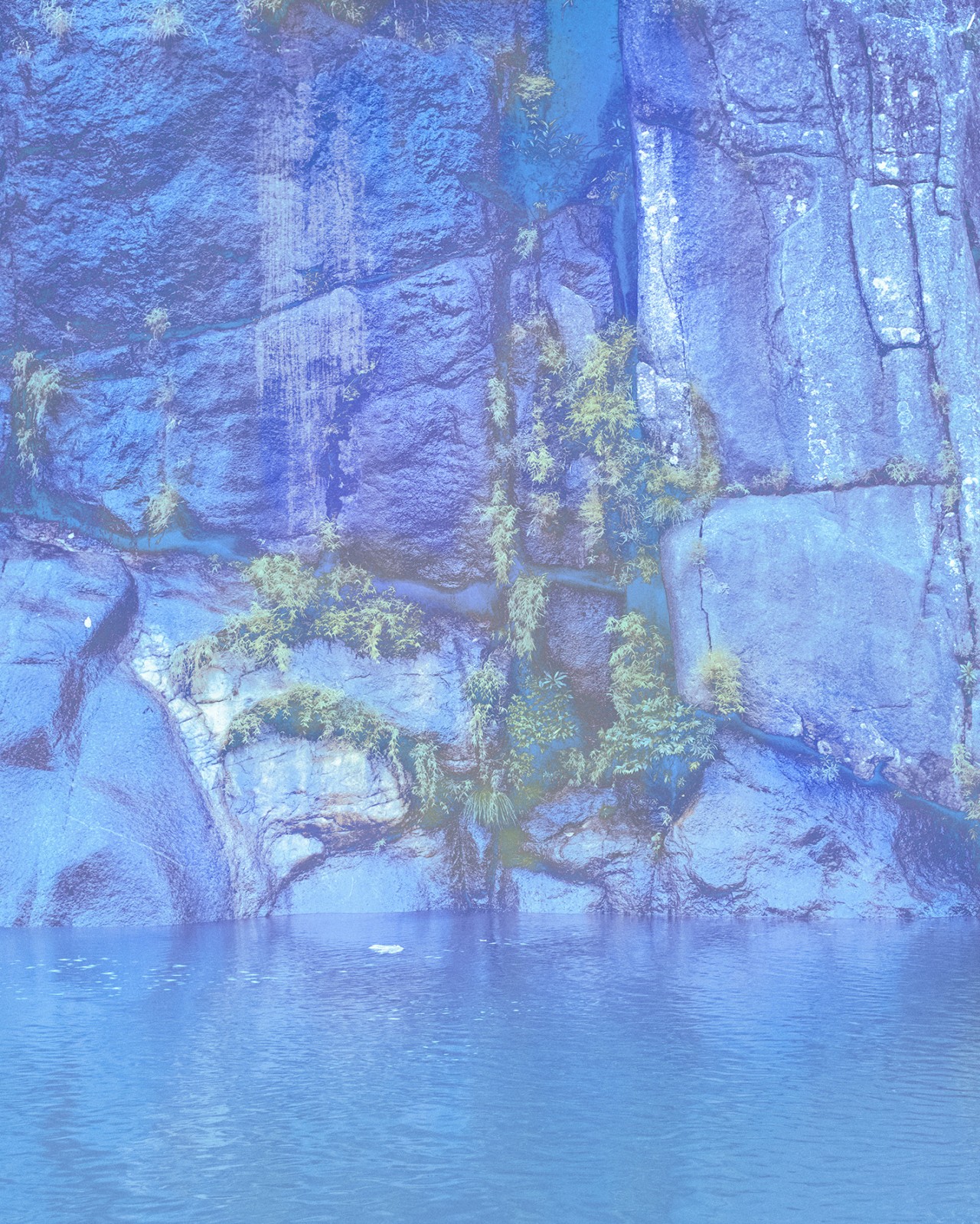

We forged on in quiet as the trail dipped up and down, bending right before suddenly revealing a magnificent rock garden. One by one, we found green patches to sit down and forest bathe. I’d only taken 200 milligrams of a psilocybin mushroom microdose—just enough to have a perceivable effect—but in one moment, several grey rocks appear to budge. Beyond that, the scene of 20 people sitting silently around a rock garden was serene. The soothing sounds of a crystal harp, carried by a young female hikrodoser, rang like wind chimes stirred by a soft mountain breeze.

“These rituals connect us all through time. Psychedelics remind us that we are an inseparable part of nature.”

As the three-hour hike concluded, we were asked to offer a single word to sum up the experience, along with a final medicine check-in. Those words ranged from “harmony” to “wonder” and “gratitude.” Some people reported threes on the high scale, but we were mostly ones, twos, and even a zero. I was a satisfied, though very hungry, one.

“If you’re not feeling OK, just stay with us for a little longer so that you feel grounded,” said Kostner, who is also a psychedelic trip-sitter. “We’re here to support you.” Then she shared details of an upcoming psychedelic-assisted breathwork ceremony she was hosting on a houseboat, along with a Day of the Dead celebration exploring psychedelics, dying, and death.

It’s difficult not to question the sales pitch of more expensive events to a suggestible group of zenned-out people in hyperplastic states, but hikrodoser Madeleine, a therapist, felt too blissful to be concerned. “I felt like I had an energetic bath,” she said. “It was very, very cleansing. I had really been craving being among trees.”

I, for one, found a sense of clarity and release over an issue that had been weighing on my mind. As we made our way back to our cars, the levels of transcendence among the wider group were hard to measure—but at least nobody got hurt or lost their keys.

‘We Are Part of Nature’: Inside the Rise of Hikrodosing