Photograph by Kimbra Audrey / Kintzing

Words by Kate Nelson

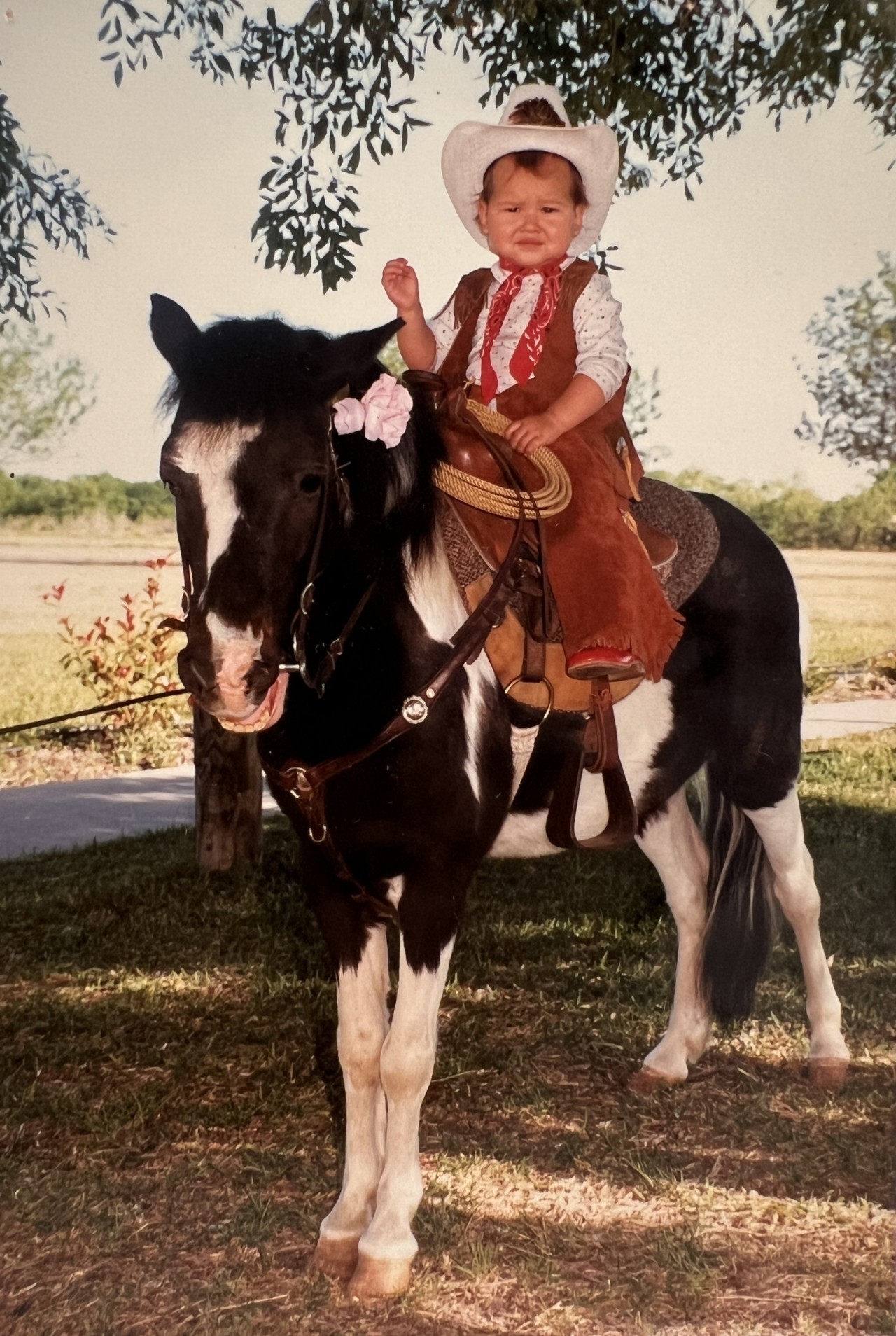

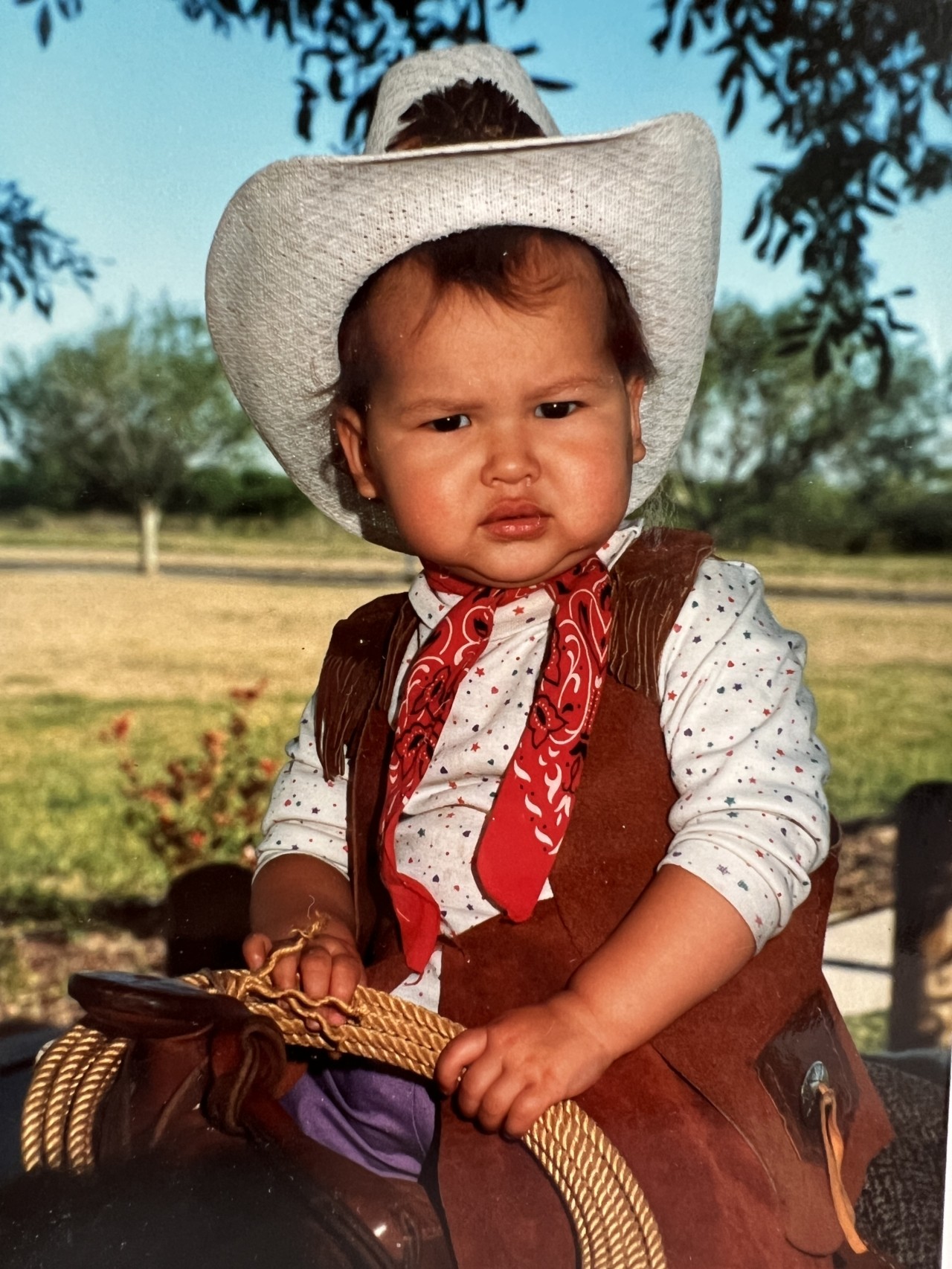

I often joke that I was a natural-born horse girl right out of the womb, but in reality my obsession with these majestic creatures formed during early childhood. Growing up, I rewatched Black Beauty, Wild Hearts Can’t Be Broken, and The Last Unicorn pretty much until the VHS tapes wore out. I plastered my bedroom walls with posters of horses and unicorns. I was absolutely mesmerized by their beauty, their grace, their freedom. And when I finally got a chance to interact with horses, I became fascinated by their innate ability to know who we are, even if we don’t yet know ourselves.

You see, as an Alaska Native (Tlingit) coming of age in rural Minnesota in the 1990s, I spent most of my childhood feeling utterly othered. I had a hard time relating to the kids around me, and my ongoing attempts to blend in with my classmates—many of them of European descent, with deep community roots—proved pretty futile. Though I forged a few friendships with the rare kind-hearted grade schooler, I found myself better connecting with animals. After all, they tuned into my intentions, my emotions, and my inner being instead of fixating on my outward appearance.

It wouldn’t be until much later in life that I’d come to several realizations about horses’ role in those early years: that their affection was some of the only unconditional love I experienced growing up. That, perhaps ironically, these massive yet delicate animals with overactive flight instincts provided a stability that simply didn’t exist in my dysfunctional, disheveled childhood household ruled by my parents’ alcoholism. And that I was far from alone in feeling like horses saved my life, as many Native Americans do.

Indigenous peoples the world over have a long history with horses, though Native and Western accounts differ. This much we know is true: Millions of years ago, the animals’ early ancestors first evolved on Turtle Island, the name many Native cultures use for North America. Based on archeological records, historians believe that they largely disappeared from the continent some 10,000 years ago for reasons unknown, with some equids having previously crossed the Bering Strait land bridge into Asia and Europe. Then, in the 16th century as colonialism swept the continent, tribal communities spread European horses across regions of Turtle Island even before European colonizers themselves arrived in those areas. Indigenous oral histories and ancestral artworks, it should be noted, attest that America’s Native horses never died out, also evidenced by the living descendants of those ancient breeds.

As we know, colonialism caused unimaginable harm to Indigenous communities, who still experience major inequities to this day, including disproportionate poverty rates, marked health disparities, outsize violence, and lower life expectancies. Horses, it seems, were one of very few things brought over by European settlers that benefited Native communities, transforming transportation, hunting, warfare, and the like. Beyond these very practical functions, these animals undoubtedly enhanced Indigenous life in ways we’re only now beginning to understand.

Recent studies show that simply being in the presence of horses, caring for them, and handling them on the ground has countless benefits, including reducing our stress, improving our confidence, regulating our emotions, and helping us find more meaning in our lives—and that’s without ever getting in the saddle. Somehow, one of the world’s most powerful yet sensitive prey animals has allowed the world’s most dangerous and destructive apex predator to strike up an improbable partnership with them. In doing so, they teach us what true trust, compassion, and vulnerability look like.

When I finally got a chance to interact with horses, I became fascinated by their innate ability to know who we are, even if we don’t yet know ourselves.

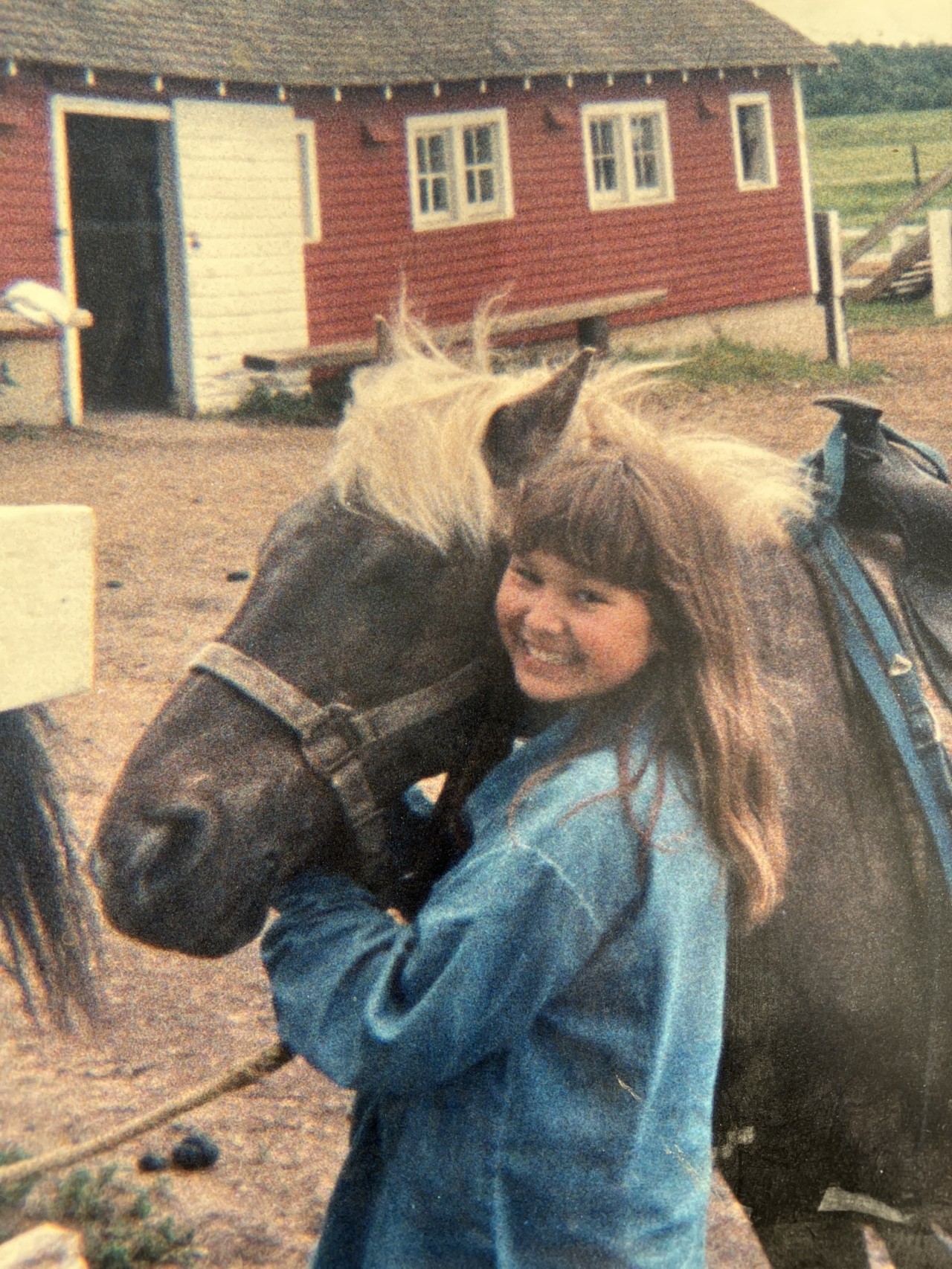

My own personal history with horses goes something like this: Despite my early-onset infatuation and my upbringing in a farming community, I didn’t have a horse to call my own as a kid. Instead, I rode friends’ horses whenever possible and spent part of my summers at a Central Minnesota ranch, learning everything I could about the cowgirl way of life. It was hard work and far from fancy, but those formative experiences sealed the deal that I was destined to be a horse lover for life.

Horse ownership is a fairly illogical notion given the massive resources it requires, and logic got the better of me when I headed off to college and into the real world. But I found myself coming back to horses time and again. One foray started off innocently enough, volunteering with a Twin Cities–based therapeutic horseback riding organization offering lessons to children and adults living with physical, cognitive, and social-emotional disabilities or conditions like post-traumatic stress disorder.

Before I knew it, I was deeply entrenched in this work and even became a certified therapeutic riding instructor. While teaching, I watched with absolute awe as horses allowed clients with limited mobility to feel the joy of walking and helped non-verbal clients feel heard in a way their fellow humans never quite could. Most evenings after I wrapped up lessons, I’d be totally overcome by tears at the wonders I’d witnessed.

It was during this time that I became aware of the empirical evidence supporting what I had always anecdotally known: that horses are inherently healing for humans. In recent years, the popularity of equine-assisted therapies and learning opportunities has grown exponentially, and for good reason. Research shows that these sessions can ease post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms, calm the nervous system, improve cardiovascular function via synchronized heart rate variability, and the like. This time spent with horses also requires us to be present in a technology-overloaded era when we’re constantly thinking about anything and everything other than what’s right in front of us.

Horses bring us back to a more grounded, harmonious relationship with the world around us in a way that’s compatible with an Indigenous worldview. At least that’s been my experience, having ridden and cared for a horse of my own for a little more than a decade. In that time, I’ve picked up the discipline of dressage, which asks horse-human partners to “dance” choreographed movements using subtle cues that are all but invisible to the average onlooker.

This sport requires a next-level partnership, which I’ve found with my “heart horse” (the equestrian term of endearment for a life-changing creature): a big, bold Warmblood named Ethel. An opinionated boss mare who takes no shit, she holds me accountable every day to check in with my intentions, my emotions, and my inner being. She sees right through any façade or front that might fool the humans in my life. And through her acceptance of who I am, she helps me better love and accept myself. In return for giving me this, I’ll give her the world (or as much of it as I can).

Illogical as horse ownership may be, having these regal, resilient animals in my life has saved me in ways I’ll probably never fully comprehend. I’ve heard the same thing from other Indigenous equestrians, whether an Olympian, an actor, or everyday riders like myself.

Horses bring us back to a more grounded, harmonious relationship with the world around us in a way that’s compatible with an Indigenous worldview.

Olympic dressage rider Adrienne Lyle (Cherokee), who has represented the United States at the London, Tokyo, and Paris games, tells me it’s in her genes. “Horses have been in my life since I was a little kid,” says the 39-year-old athlete. “A lot of times, they’ve made more sense to me than people do.” She hopes to leave a lasting legacy of nurturing not only talented riders but compassionate horse people who always put the welfare of the animal first, like her longtime assistant, Quinn Iverson (Tŝilhqot’in).

Meanwhile, actor Mo Brings Plenty (Lakota) tells me he was contemplating leaving Hollywood, fed up with playing stereotypical Native characters and fielding ignorant requests from industry execs. Then a chance encounter with a rare Nokota horse—believed to have descended from Sitting Bull’s horses—brought him back from the brink. It reminded him of the important role these animals have played throughout his life, during his childhood on the reservation and his days trying to make it in the rodeo.

“If it weren’t for horses, I honestly don’t know who or where I would be today,” says the 55-year-old actor, who dealt with incredible shame and faced discrimination for much of his early life. “Without them, I wouldn’t be grounded. I wouldn’t know how to be strong without being cruel to others. Horses are so strong and protective, but they do it in a way that’s still respectful to others.”

As often as I jest that I was born equine-obsessed, I also attest that the world would be a better place if more humans had horses in their life. There’s even scientific research to support what might otherwise seem like a far-fetched theory. But even beyond the data, it’s pretty apparent that these animals—in so many ways so different from humans—can help remind us of our shared humanity through their empathetic, open-hearted ways; that they can help inspire us to live in better harmony with the beings around us. Just take it from a horse girl like me.

Like So Many Native Americans, Horses Saved My Life