WORDS BY SOPHIE PAVELLE

Artwork by Juul Kraijer

A body-snatching barnacle. A brain-burrowing worm. A lichen whose body divides into an impossible three. When you hear the word parasite, what springs to mind? Monsters lurking in the shadows, or marvels of biological ingenuity?

To describe a parasite is to describe the world. Nearly half of all animal life is parasitic, while virtually all free-living animals host at least one type of parasite. Our own human bodies host at least 400.

Though often vilified, parasites are the forgotten architects of the living world. They bind and dominate the food webs that shape communities and guide evolution. They can even alter the environment, sometimes reducing the load of environmental pollutants experienced by their host. What may seem like a destructive host–parasite dynamic is, in reality, part of the fabric of ecosystems: an intricate dance of precision, intention, and cunning.

Only foolish parasites kill their host; smart ones hold them close. What if humans could learn from that? What if we mirrored the restraint, reciprocity, and sustainability of Earth’s most successful exploiters? Could this new sort of parasitic relationship offer our host planet the chance to survive—maybe thrive—in balance?

Parasitism, which has evolved at least 223 times, is symbiosis in its most ubiquitous form. Symbiosis was introduced to science by German botanist and mycologist Heinrich Anton de Bary in 1878. Focusing on lichens as the striking alliance between fungus and algae, de Bary defined symbiosis as “the living together of unequally named organisms.” Parasitism is a thrilling subset of symbiosis in which one species benefits at the expense of another. During their time together, the host may or may not suffer. The host may or may not die.

Evolutionary biologist Dr. Lynn Margulis famously argued that symbiosis is not an exception, but the root of life itself, responsible for the evolution of organelles like mitochondria and chloroplasts. Since its genesis, the tree of life has branched through chance, tension, and opportunity, its tips entwining through symbiotic alliances. Species contend and negotiate, fusing in networks that pulse with resilience.

But seen through the eyes of parasitism, symbiosis is not as harmonious as textbook examples might suggest. Nature is less egalitarian than unruly; it’s vital, inventive, and uncompromising, distinguished by precisely executed raw inequality and reciprocal exploitation.

Stories of ancient symbiotic bonds filled my notes as I wrote my recent book, To Have or To Hold: Nature’s Hidden Relationships. Three years of writing and still, my mind coalesces, connecting evolutionary tales in a mycelial network. For me, symbiosis, as parasitism, illuminates Earth at work.

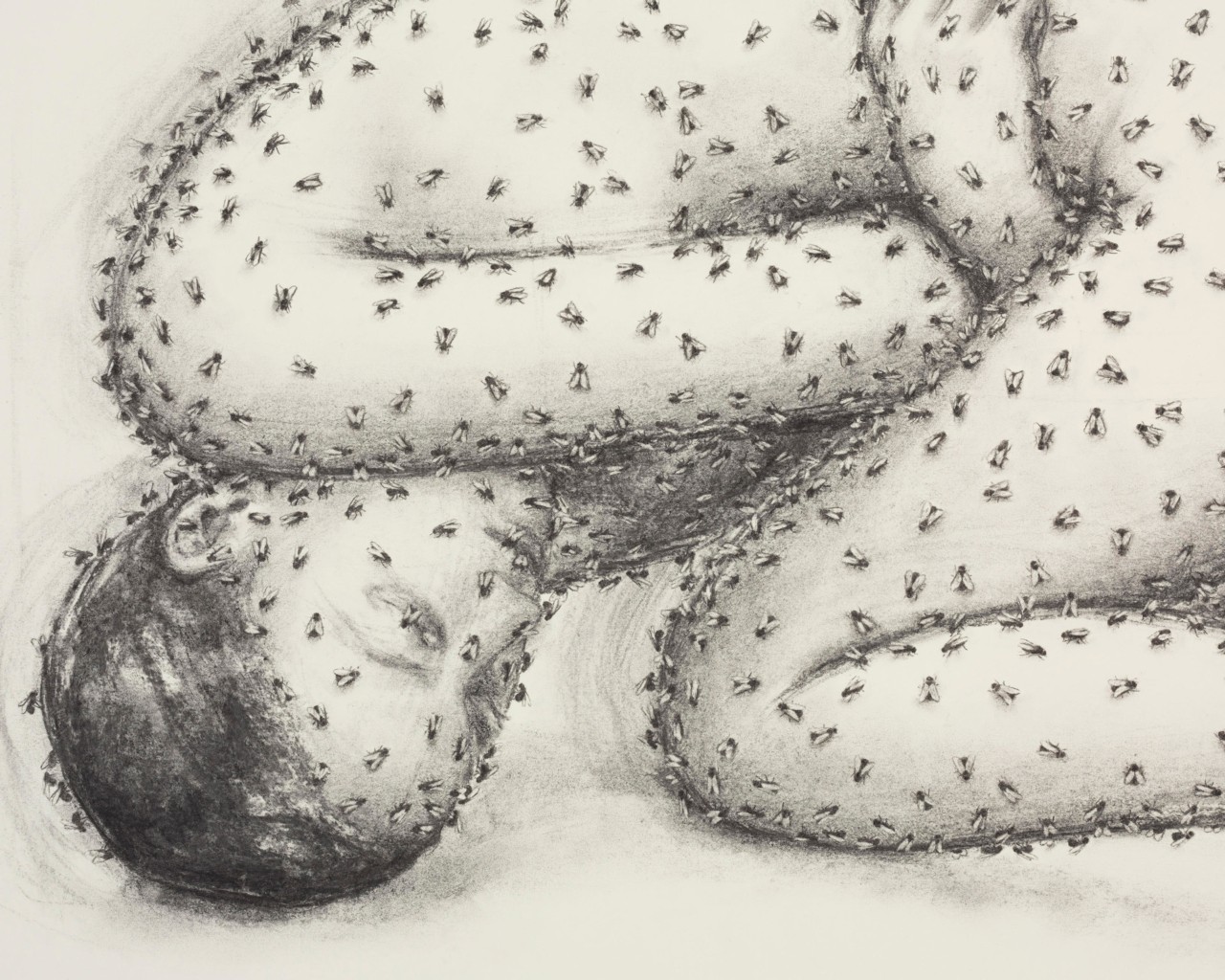

Far from casual intimacy, symbiosis demands dangerous lifestyles. I think of the crab-hacker barnacle (Sacculina carcini), a western European and north African species who parasitizes the green crab (Carcinus maenas). Green crabs are considered one of the marine environment’s most invasive species, and the barnacle’s parasitic lifestyle is so prolific that scientists have contemplated deploying it as a biological control agent in the United States.

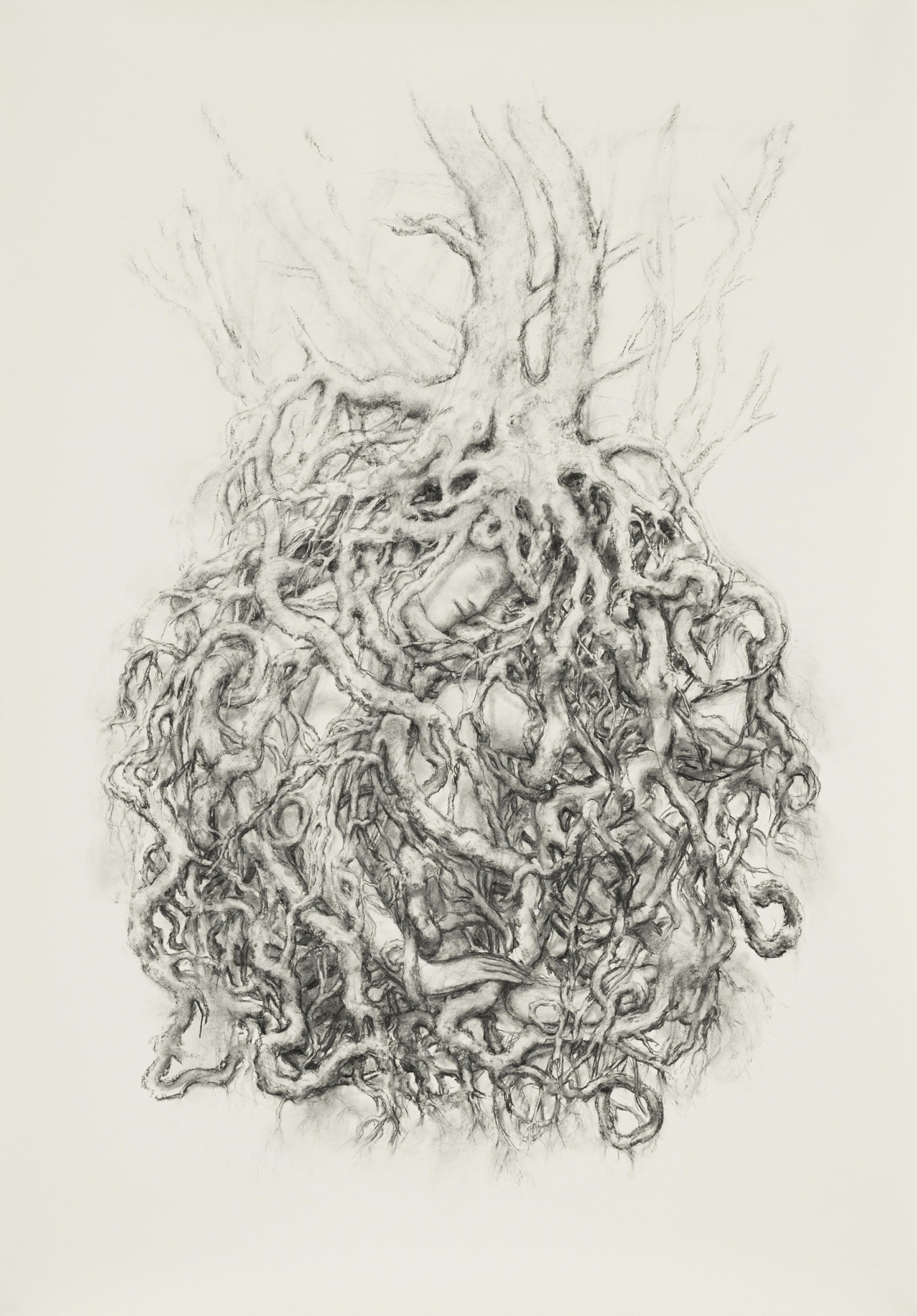

Female Sacculina larvae detect freshly moulted crabs by smell, entering their bodies fast and unseen. The barnacle destroys the crab’s sex organs—a macabre yet rampant parasitic strategy—and, should the crab be male, feminizes her unsuspecting host. The barnacle then grows, flourishing in a root-like network. Tendrils creep and crawl, feast and fuse, siphoning nutrients from the crab’s tissues, an intimate collision of blood, brain, body. Her goal is prosaic and maternal: Fool the crab into parental care.

Infected crabs—both females and feminized males—oxygenate the barnacle’s eggs like they would their own and seek places with fast currents to disperse the larvae, all while perpetuating the parasite’s growth. Eventually, the barnacle penetrates the crab’s underside and extends her sac of sex organs, uncannily similar in appearance to the crab’s own egg sac, into open water to be fertilized by males. Once the larvae are finally released, the barnacle’s external protrusion can detach or degenerate, severing ties with the internal, root-like form, which remains inside the crab, leaving nothing but a blackened scar on the abdomen. How draining the ordeal is for the crab host in the long term remains to be fully understood.

What feels barbaric is a refined operation. Like all parasites, Sacculina must keep their hosts alive during their time together, exploiting the crab’s bodily bounty with systematic precision. Despite depleted energy reserves and internal damage, some crabs can survive the occupation. In other species, parasitic castration is but a temporary affliction, and host reproduction can resume.

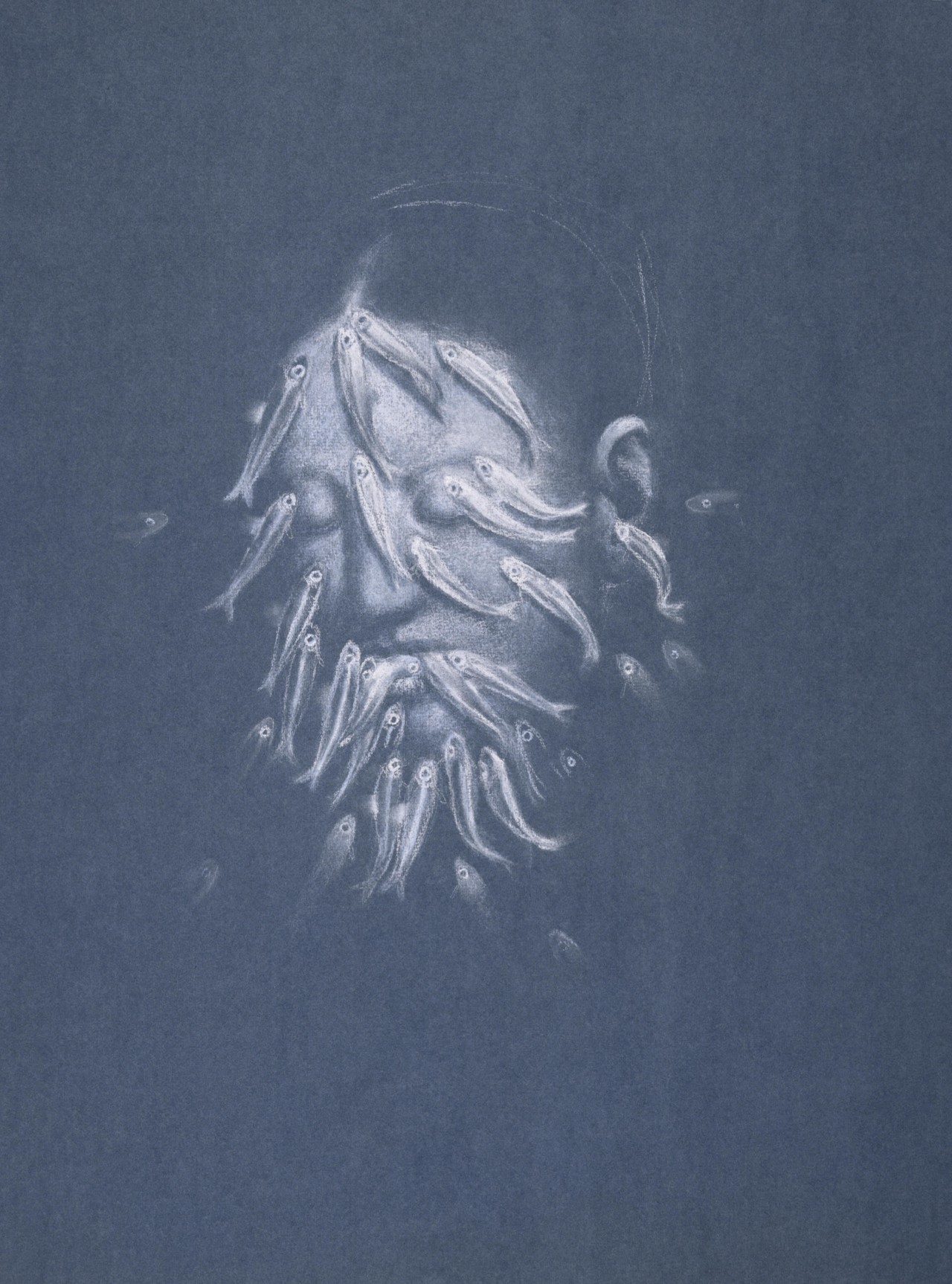

Some parasites can alter the environment in ways that, deliberate or not, benefit their hosts. For instance, some tapeworms can tolerate heavy loads of toxic metals. While occupying their host, some spiny-headed parasitic worms (acanthocephalans) can absorb environmental toxins from the surrounding environment, lowering the overall pollutant burden in the host’s bodily tissues.

“Only foolish parasites kill their host; smart ones hold them close. What if humans could learn from that?”

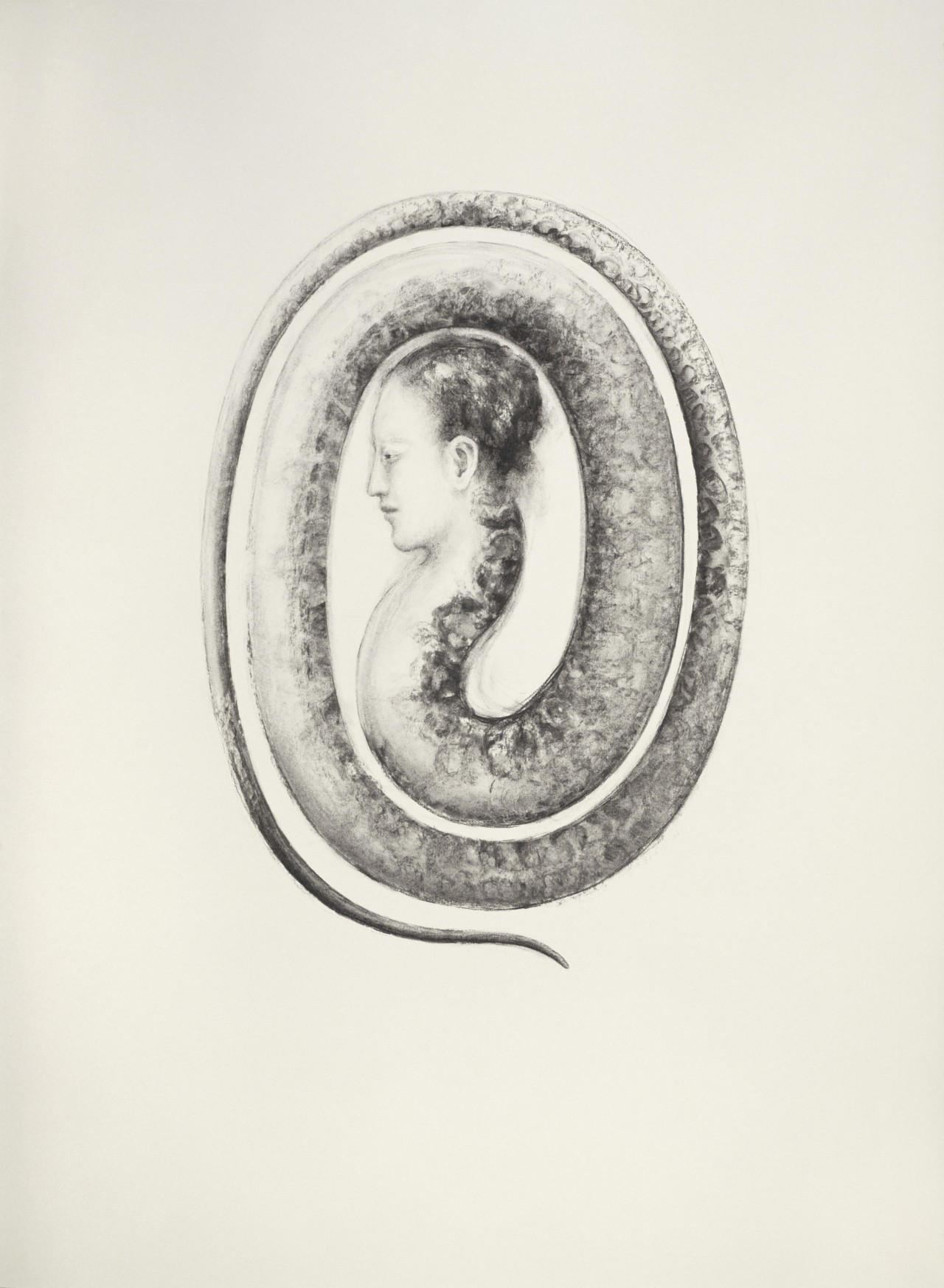

Other parasitic relationships can be more covert. Botanist Dr. Robin Wall Kimmerer writes in Braiding Sweetgrass of the blur between individual and union while observing lichen—a composite lifeform similar to coral, in which fungi receive nutrients from symbiotic, photosynthesizing algae or cyanobacteria. Kimmerer compares the exchange of resources in lichens to the compromises that underpin a successful marriage. But I found their relationship less marriage and more marketplace. The division of labor between lichen’s trio of fungi, algae, and cyanobacteria can be unequal. Parasitism lingers in the margins of their vow. Indeed, scientists have long debated whether lichens are mutualistic, benefiting both parties, or parasitic—the algae a prisoner who is farmed by the fungus.

Parasitism tests our acceptance of nature’s ferocity. Symbiosis, after all, is as ruthless as it is tender. Our human negativity bias swerves our attention away from this ecological dark matter, hiding the lessons parasites teach and the company they keep.

As we confront our own existential reckoning, consuming our host planet at a relentless pace, I can’t help but wonder whether parasites offer strategies for mutual survival.

Parasites don’t just model sustainability in their careful acts of extraction and restraint; they embody a living, pulsating source of biodiversity. Unlocking these lessons requires a mental shift: to view parasites with a sense of revelation rather than revulsion. It also requires saving them from climate change itself, to avoid severing them from hosts with whom they’ve sometimes evolved in lockstep. Do we have what it takes?

It is no coincidence that many symbiotic and parasitic relationships revolve around water. The alliance between unlike organisms surges, thrashes, and sustains like a river. As with water, I imagine symbiosis as a kinetic entity—more verb than noun, shaping the banks of life around it.

In researching my book, I spoke to biologist Dr. Xavier Bailly. He précised de Bary’s 1878 definition of symbiosis as simply: “symbiosis, who lives with.” In this, I see parasitism as a summoning, a call to action. To be involved—deeply, joyfully, complicatedly—with life.

How To Be a Better Parasite