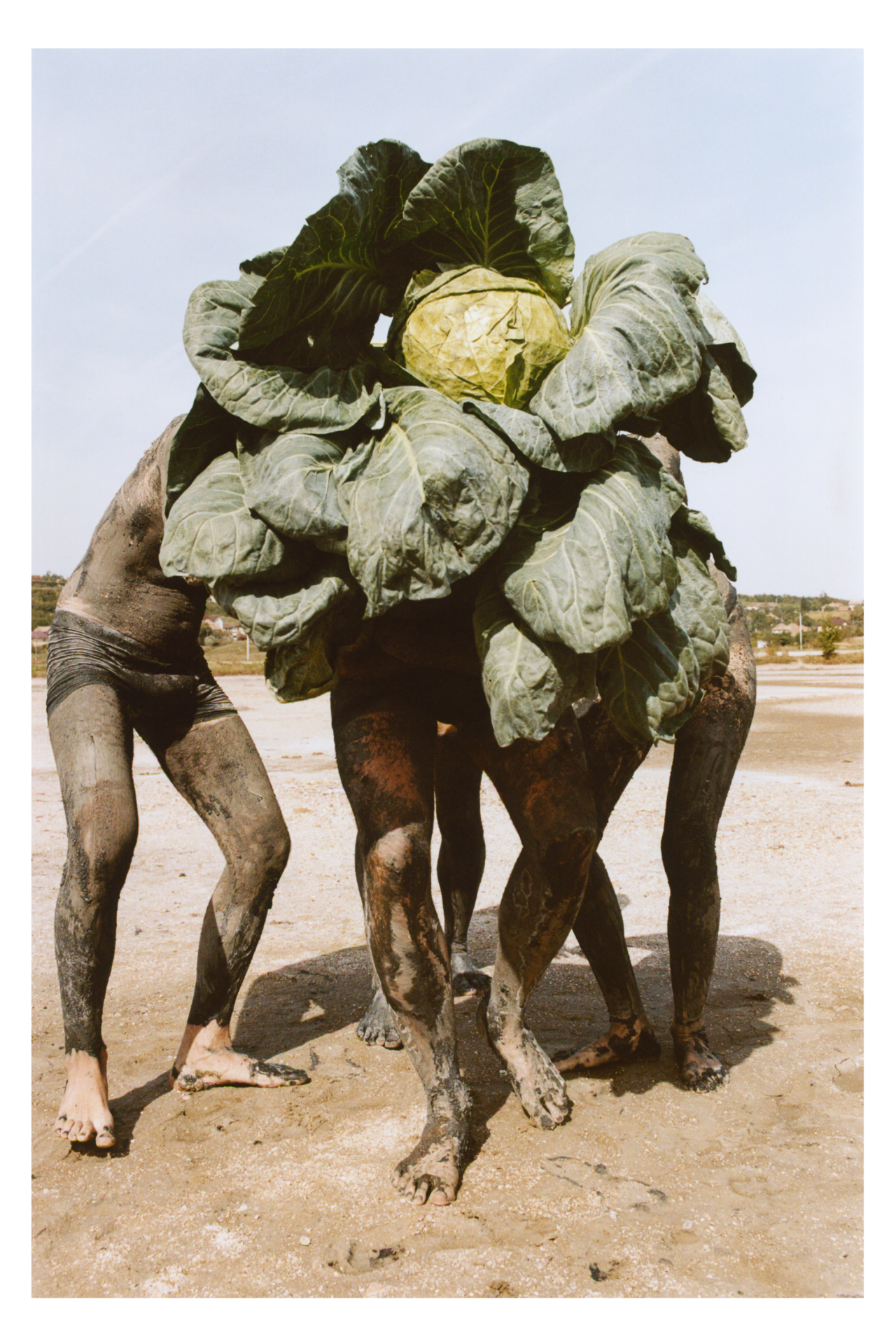

Taken for Atmos Volume 09: Kinship, these images depict mud bathers in Turda, Romania, who regularly immerse themselves in wet soil—the silt on their skin washing away identity, leaving only earthen sculptures behind.

WORDS BY ROMANY WILLIAMS

photographs and set design by Clarisse d’Arcimoles and Toby Coulson

Author Ferris Jabr opens his new book, Becoming Earth: How Our Planet Came to Life with a quote from science fiction writer Octavia Butler’s prophetic novel, Parable of the Sower. “Consider: Whether you’re a human being, an insect, a microbe, or a stone, this verse is true. All that you touch, you change. All that you change, changes you.”

In Becoming Earth, Jabr endeavors to tell the story of life on planet Earth from the very beginning. A tremendous undertaking, he expertly revisits inventor and chemist James Lovelock’s seminal 1970s Gaia hypothesis while exploring contemporary climate solutions to form a compelling Earth system science manifesto. Jabr sees his book as part of a larger emerging movement born from the now-legitimized thesis of the Gaia hypothesis: that life has dramatically transformed the planet and is integral to its self-regulating processes. In a way, Jabr writes, Earth is alive.

“We and other living creatures are more than inhabitants of Earth; we are Earth—an outgrowth of its physical structure and an engine of its global cycles,” writes Jabr. “Earth and its creatures are so closely intertwined that we can think of them as one.”

In that context, humans are but the latest in a lineage of terraformers, only we’ve altered Earth’s living systems more dramatically than any species before us. Just think of how much carbon we’ve taken out of the ground and spewed into the atmosphere over mere centuries. “Our species is the latest in a long line of life forms that have profoundly altered Earth,” said Jabr in an email. “In that sense, we’re not different in kind—but the combined speed, scale, and scope of our transformations is unique. No species before us has radically changed so many different aspects of the planet in so little time.”

From his home in Portland, Oregon, Atmos connected with Jabr to discuss the ongoing relevance of Gaia, the intelligence of the Amazon rainforest, the mind-bending nature of plastic, and how he finds solace on our ever changing planet.

Romany Williams

With topics like war, human rights, and climate at the fore, today’s cultural and political zeitgeist feels, in many ways, not dissimilar to that of the 1970s when Lovelock’s Gaia was first embraced by the public. How has the Gaia hypothesis remained relevant today?

Ferris Jabr

People our parents’ age or older are more familiar with Gaia because they may have read the original book when they were young. The theory has fallen a bit to the wayside and the name Gaia still has a stigma attached to it, but the central tenets of Gaia have become part of mainstream Earth system science.

Over time, the evidence of the coevolution of Earth and life has become overwhelming. It’s accepted among Earth system scientists that life is very much intertwined with the Earth’s innate capacity to regulate its climate. The planet seems to have some sort of self-regulating processes—the carbonate-silicate cycle, for example—that allow Earth to keep its climate within a range that is permissible for life. When it enters a hot house or deep freeze state, it pulls itself back. While that process can involve mass extinctions, for more than four billion years and counting, Earth has remained habitable for life, and we have to account for that incredible resilience and longevity somehow.

Romany

If Earth and life have coevolved, does that make the Earth “alive” so to speak?

Ferris

Today, we know that Earth and life change each other dramatically, that life is a major geological force, and that life is intertwined with these self-regulatory planetary processes. I don’t think Earth is an organism or even a superorganism. I think we need to get past the idea that life is synonymous with organism and recognize that the phenomenon we call life happens at many scales.

Stating that Earth is “alive” or a living entity remains provocative, but there are scientists that I interviewed who are completely comfortable with that. They embrace Earth being a living planet, which is very different from a planet that just simply has life on it. We need to get away from this idea that life simply resides on or inhabits a planet and start to see life as a physical extension of the planet.

I like to make the analogy of a giant beach from which sandcastles and other intricate sculptures spontaneously emerge. Just because they’ve arisen from the beach and attained a new level of complexity doesn’t mean they’re suddenly divorced from the beach around them. They’re still made of the same particles of sand. I think it’s the same with life and Earth. Life literally emerged from Earth, it’s an extension of Earth, it loops back to transform the planet. Together, Earth and life form a single living and evolving system. We are literally extensions and expressions of the planet, not just inhabitants on a spaceship Earth or a thin layer of life that is clinging to this larger inanimate entity.

Romany

In Becoming Earth, you write that the most formative moment in your journey towards planetary-scale thinking came from reframing the Amazon rainforest as a “garden that waters itself.” From an Earth system standpoint, what makes the Amazon so fascinating?

Ferris

Around 2014, I learned about the Amazon’s self-generated rain cycle. The Amazon continually spews an invisible plume of tiny biological particles from pollen grains, fungal spores, and microbes, to volatile gasses, salts, and minerals. All those biological particles give the water vapor something to condense onto, making the ideal conditions for rain. I didn’t learn that in high school or college. I didn’t think that ecosystems made their own weather to that degree. I started thinking of the Amazon almost as a garden that is watering itself. Scientists have written that the Amazon has retained its essential characteristics for 55 million years, describing it as a biogeochemical reactor. Immediately to me, there was something Gaian about that system.

“Life literally emerged from Earth, it’s an extension of Earth, it loops back to transform the planet.”

Romany

“Gaia” comes from Greek mythology, and that name choice played a big part in scientifically delegitimizing the valid arguments in the Gaia hypothesis. Expansive topics like this seem to necessitate imagination, and drawing from things like mythology and science fiction can be quite helpful to broaden public understanding, but they are still stigmatized by science.

Ferris

While on a walk with James Lovelock, William Golding, author of Lord of the Flies, suggested that Lovelock call this living system Gaia. To be totally honest, I think that was a big mistake in a lot of ways. I don’t think it needs a separate name because Earth already has a name. Although I don’t agree with the scientists who responded this way, it did kind of set up the entire hypothesis with this inbuilt mysticism that became an easy target.

It’s crucial to recognize that the concept of a living world or planet is ancient. It goes back further than we have records of any kind. It’s clearly something that many Indigenous cultures intuited about the world. It makes sense why so many of our artists, writers, and philosophers have been more comfortable with exploring this idea earlier than Western science was able to.

Romany

I spoke to author Zoë Schlanger recently about the debate surrounding plant consciousness, and I think that dialogue naturally extends to Becoming Earth. If we think of the Earth as a living entity, and humans as part of the larger spherical metabolism of the planet and its layers of atmosphere, water, and air, could we perhaps posit that we are functioning as part of the Earth’s consciousness?

Ferris

I’m very sympathetic to that view. Since I’m arguing that we accept life as an extension of the planet, then in some ways we also have to accept that Earth is aware of itself. I like that this doesn’t necessitate panpsychism. You can still restrict consciousness to particular projections of something rather than having it be a universal quality. A lot of people latched onto Gaia and interpreted it as more than just alive, but as sentient. I love thinking about all the individual conscious beings on the planet being this collective consciousness of Earth.

Romany

You spent time with scientists in Hawaii at Kamilo Beach, the site of tremendous plastic pollution. Here, hybrid materials of rock and plastic form a new type of rock coined “plastiglomerate”. Some scientists have proposed that plastic and plastiglomerate will become a significant part of the geological record.

It seems like every day there is a new and horrifying development about microplastics and the extent to which they are infiltrating and potentially poisoning every facet of life on Earth. How does plastic fit into the anthropogenic Earth system? Over time, will the Earth’s bones become plastic?

Ferris

Plastic is made from fossil fuels, and fossil fuels are the remains of ancient creatures like plankton and other marine life. The Earth has an incredible built-in system to move carbon through different layers of the planet, which largely dictates our climate. Plankton are a very important part of that process—they’re constantly transporting carbon to deep sea sediments via their fecal pellets or when they die and sink. At the seafloor, they become sediment that compacts and becomes stone, which is eventually subducted and then the carbon is returned to the atmosphere through volcanic activity and outgassing.

But then we come in. We unbury all of this dead plankton in the form of fossil fuels and not only do we burn it and release all the carbon into the atmosphere, but we take some of it and turn it into plastic. So now we’ve taken ancient plankton, turned them into plastic, and then polluted the modern ocean environment with plastic, which then breaks down into an uncountable amount of microplastic, that then go on to act in eerie ways like true plankton by also sinking to the ocean and settling in the sediment. Large organisms start to eat them as though they are plankton. This is such a new phenomenon we don’t even know what it’s doing to the marine carbon cycle. It makes you look at plastic objects in your life in a whole new way. The idea of microplastics as a kind of necromancy, that we’ve resurrected ancient plankton and turned them into imposters in the ecosystem of the ocean, haunts me.

“I take solace in the fact that whatever our species does to the planet, I think that the living system as a whole is going to make it.”

Romany

The view that humans are a sort of menace, a cancer to the Earth and its biggest opponent is pervasive in online climate discourse. In the epilogue you write, “we are neither the cancer of Earth nor its cure. We are its progeny, its poetry, and its mirror.”

Ferris

What Earth history and Earth system science shows us is that Earth is an incredibly complex and resilient system that is also highly vulnerable. I think that multiplicity is hard for a lot of people to wrap their heads around, including scientists.

We know that complex living systems tend to, or attempt to, persist through time. We see that on the scale of the cell, the organism, the ecosystem, and the planet. If they have enough time and opportunity, they’ll find ways to perpetuate themselves. To me, that seems to be the defining quality of all living systems. When they are perturbed too much, they can collapse, die, or recover. This has happened to the Earth’s system at least five times, and every single time it has recovered.

I take solace in the fact that whatever our species does to the planet, I think that the living system as a whole is going to make it. The question is, are we going to destroy our way of life? Our version of Earth that we have depended on for so long? There’s something to hold onto when you embrace a deep-time perspective. I like to look at what science actually shows us and try to find a balance of realism, courage, and inspiration.

Talent Moga Marius Dan, Norbert Filep, Stefan Buga, Madalin Margaritescu, Alexandra-Maria Berar PHOTOGRAPHY ASSISTANT Moga Marius Dan POST PRODUCTION Sipke Visser, Rapid Eye Darkroom

These images first appeared in Atmos Volume 09: Kinship with the headline “The Way of the Salamander.”

Editor’s note: This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Earth Is Alive, a New Book Argues. Will We Kill It?