words by jason p. dinh

Photographs by Philip-Daniel Ducasse

Claudine André still holds on to Mikeno’s first baby tooth. It’s a memento of the youngster, now deceased, who changed the course of her life.

Mikeno, named after a volcano in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) that André climbed in 1971, was always attached at her hip. He couldn’t speak, but his emotions rang clear through his actions. It’s how she got that tooth, she recalled. She pulled it out three decades ago during a rainforest hike, after Mikeno nuzzled her and pointed straight into his mouth at the culprit. You’re not going to like this, André told him before yanking it clean from his gums.

André already had four children at the time, but Mikeno wasn’t one of them. He was a bonobo, the first she ever rescued.

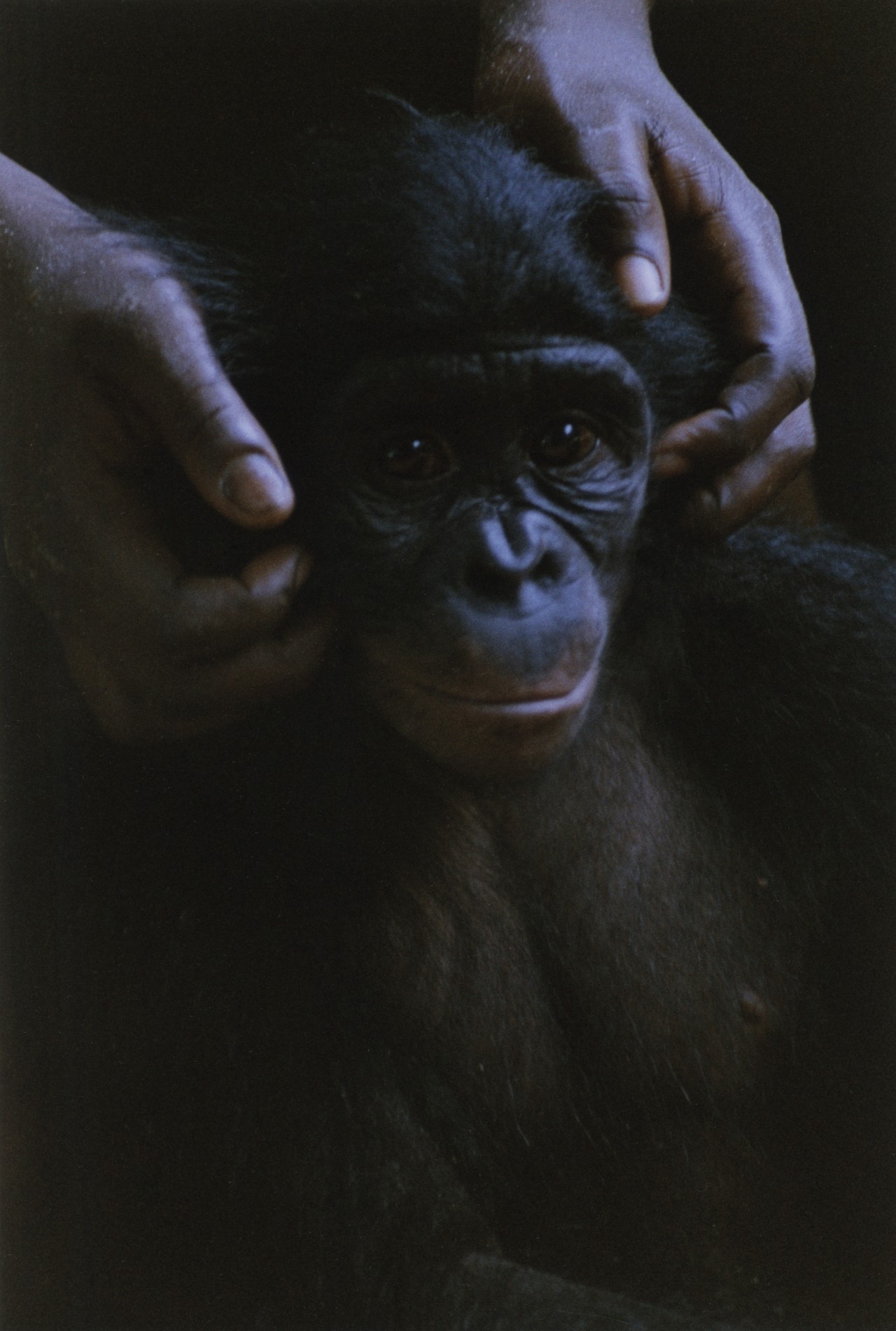

André had loved animals her whole life—her father was a vet—but something about Mikeno was unique. He didn’t just look into her eyes, she reminisced. He looked into her soul. “Mikeno was so strange, so very sweet,” she said.

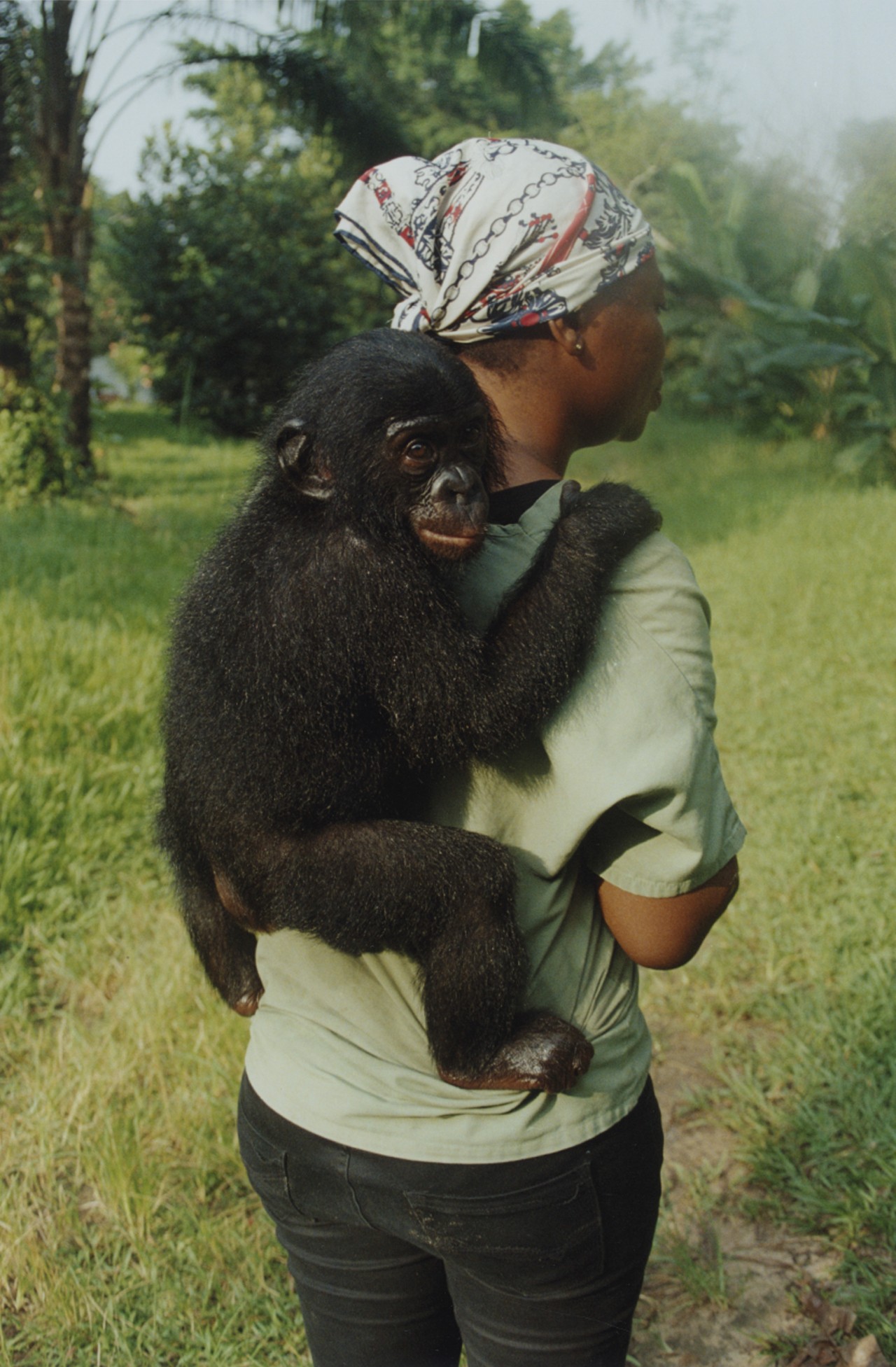

André, now 77, would care for many more orphaned bonobos throughout her life. At first, she welcomed them into her home in Kinshasa, the capital of the DRC. Then, she moved them to a defunct school nearby before establishing a 75-acre forested sanctuary 18 miles south of the city in 2002. She named it Lola ya Bonobo, meaning paradise for bonobos.

André’s care provided the primates a much-needed respite from political strife. The Rwandan genocide occurred across the border soon after André started taking in bonobos. The resulting turmoil, along with some militiamen responsible for the massacre, spilled into the DRC, destabilizing the government and leading to a decade of civil war. The conflict, during which five million people died, caused hungry people to poach bonobos for bushmeat.

Some places lost 60% of their bonobo population. Many surviving infants were either stranded or sold as pets.

Skeptics told André not to get attached. Every orphaned bonobo brought to Kinshasa Zoo before Mikeno had died. Food and medicine alone weren’t enough to sustain them. But they hadn’t had a doting mother figure like André. She bonded with, embraced, and nurtured the bonobos under her care—and she succeeded. The secret, she discovered, was to treat them the way they treat each other: like loved ones.

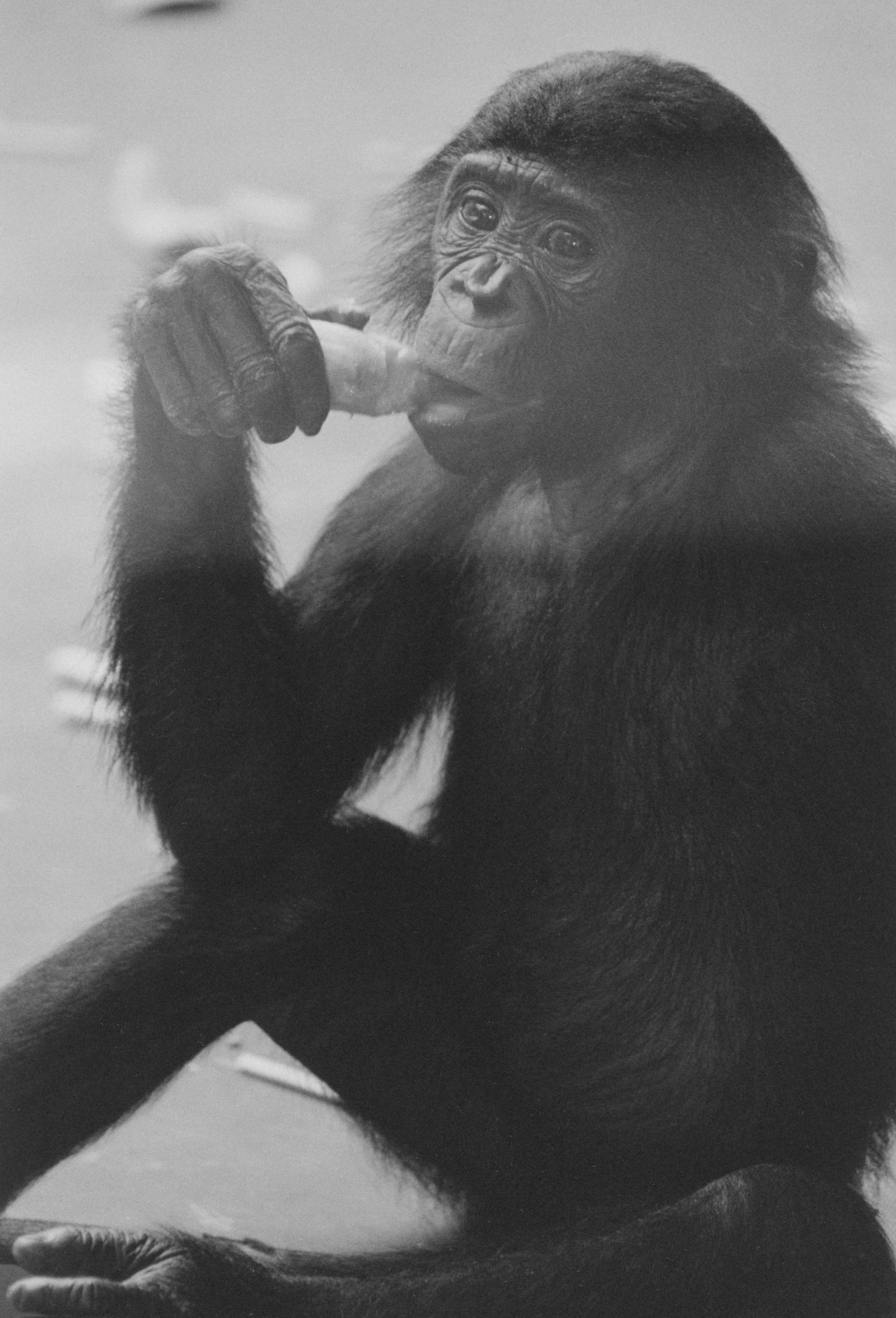

Bonobos, endemic to the DRC, are nicknamed the “make-love-not-war ape.” Unlike other primates, they don’t murder each other. They greet, bond, and reconcile disagreements with sex. A council of females subdues aggressive males and maintains peace. Individuals from one social group will even cooperate with those from others; traveling, sleeping, and sharing meals together. And although a recent study showed that male bonobos fight amongst themselves more frequently than male chimpanzees, those tussles are far less intense.

Their disposition sharply contrasts with their closest relatives, chimpanzees. Like people, chimps have vibrant personalities, but they also have a dark side. Male patrol groups viciously defend their territory from neighboring groups. In rare cases, they even kill outsiders, according to Liran Samuni, a behavioral ecologist at the German Primate Center in Göttingen. While bonobos regularly help those outside their social groups, “in chimpanzees, you will never have a situation in which one group tolerates individuals from the other,” Samuni said.

That’s not to say that chimpanzees are evil. “If you look them in the eyes, you see a real person looking back at you with the same will and personality and strengths of character that we have,” said Frans de Waal, a primatologist at Emory University.

“Chimpanzees are definitely not villains,” added Brian Hare, an evolutionary anthropologist and cognitive scientist at Duke University. “They’re just like people in that they have a wonderful side to them, and they have a darker side.”

Chimps and bonobos are humanity’s closest living relatives, and in a way, we can see both within us. We can be altruistic to strangers and, in the next breath, unfathomably cruel; we can donate kidneys to those we’ve never met, but we can also kill and massacre.

Imagine a world where our inner bonobo overruled our inner chimpanzee, where our tolerance toward those who are different outweighed our prejudice. Bonobos wouldn’t wage war or commit genocide. Maybe they could even work together to fix our climate. De Waal finds that plausible.

“Bonobos are more concerned about each other and each other’s feelings, so I usually call them the most empathic ape,” de Waal said. “The bonobo, I think, would be more inclined to take the bigger perspective [on climate change] and be concerned about humanity as a whole.” After all, confronting global crises requires between-group cooperation—the bonobo’s specialty. Maybe they can show us the way.

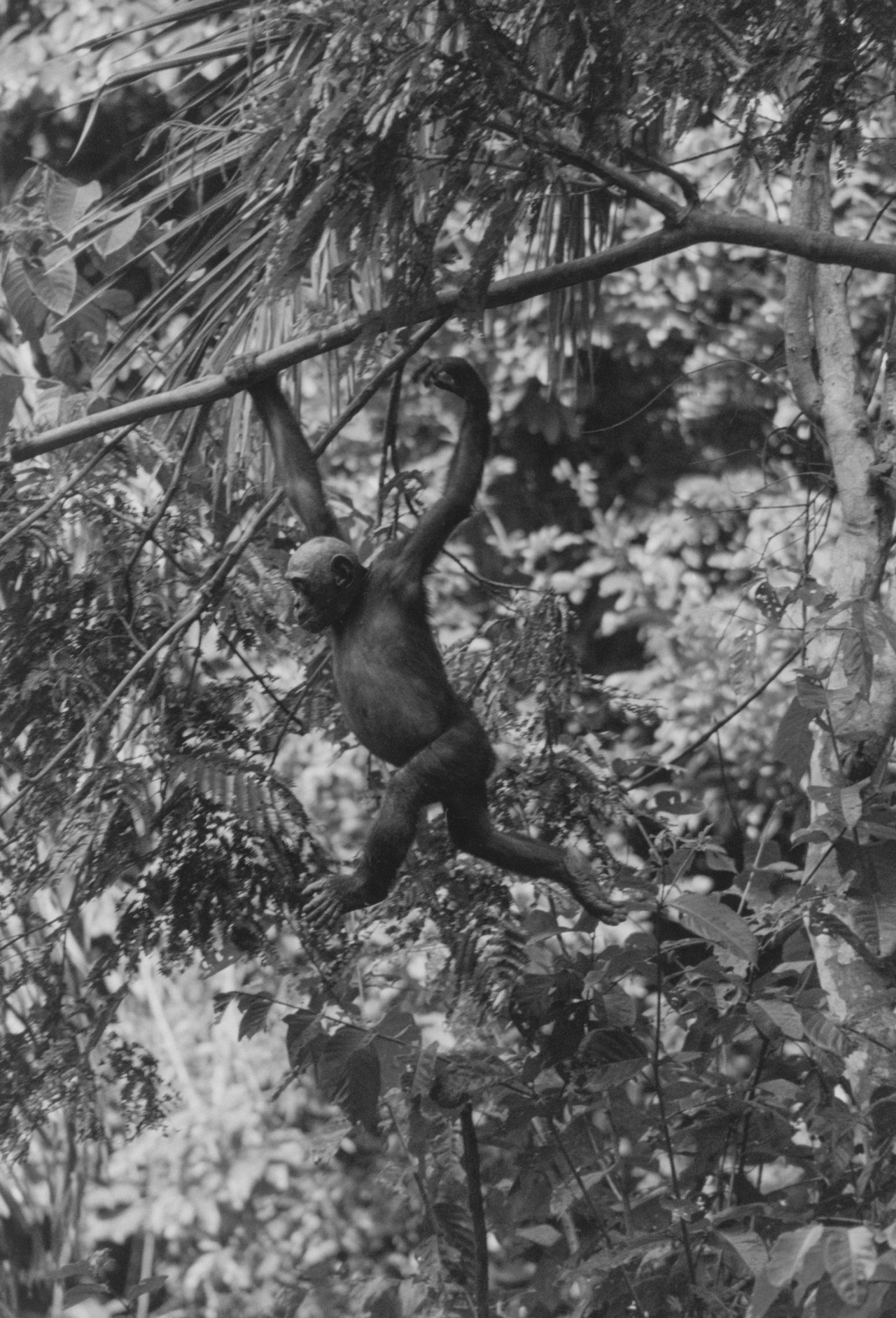

About one or two million years ago, the common ancestor of chimpanzees and bonobos ventured south of the Congo River. There, they encountered a new world: one with ample resources, stable food, and no gorillas with whom to compete. That abundance, one leading theory posits, allowed bonobos to become peaceful.

Normally, when chimpanzees face tough times, they switch from their fruit-and-meat diet to stems and shoots. With mostly vegetarian gorillas around, chimps face fierce competition for greens. That takes an especially heavy toll on low-ranking females, who get relegated to societal margins and must defend whatever they can find. They can’t afford to make friends, the theory goes.

But south of the Congo River, where vegetation grows lush, maybe they could. With less competition, there was little need for violence, the theory continues. Perhaps friendships became beneficial, helping females defend each other and their offspring from murderous males. Here, in a luxuriant paradise, survival of the fittest may have meant survival of the friendliest.

“Bonobos taught me a lot about being human. Perhaps the bonobo taught me more about serenity and peace than anyone I ever met.”

Neither de Waal nor Samuni are fully convinced yet. But Hare, one of the researchers who recently synthesized the idea, stands behind it: “When I have tried to falsify it and when others have tried to falsify it…the idea has held up.”

Much of the evidence relates to a suite of traits called domestication syndrome, which arises whenever species are selected for friendliness. The correlated evolution of these traits came to light when Russian scientists experimentally domesticated silver foxes. They selectively bred them based on a simple test: their willingness to approach a human hand. Within six generations, the foxes whined and craved human attention like dogs. Surprisingly, they looked and thought more like them, too.

They had curly tails, mottled pigmentation, and shorter and rounder faces. They also became better at reading human social cues. The researchers didn’t breed them to be that way; rather, these hallmarks of domestication syndrome arose because they were somehow linked developmentally to friendliness.

Hare argues that bonobos also exhibit domestication syndrome. Compared to chimpanzees, they have shorter faces, smaller skulls, patches of depigmented fur, and an enhanced ability to read our gaze. He thinks these features are evident in people, too: For example, our skulls have shrunk in the past 200,000 years, and we have depigmented sclera in our eyes. Hare sees that as evidence that people and bonobos were also selected for friendliness, but unlike the Russian foxes, this arose through natural selection rather than artificial breeding—what he calls self-domestication.

De Waal isn’t convinced yet. For starters, he has semantic qualms. Human domestication has a rotten history, with some scientists like Konrad Lorenz using the term to justify eugenics and Nazism. Hare acknowledges this, but he asserts that it’s more complicated than that. The term’s long, checkered past includes equity-minded anthropologists, too, like Franz Boas—a prominent twentieth-century opponent of scientific racism. The modern usage, Hare maintains, shouldn’t be conflated with its most disturbing chapter.

As for the validity of the science of domestication syndrome itself, de Waal thinks there may be other viable alternative theories. “There are multiple ways of reaching a peaceful state, and I’m just not clear that self-domestication is necessarily the answer,” he said.

Hare encourages skepticism. “I’m a scientist. I’m trying to create an explanation that can be falsified,” he said. But it hasn’t been yet, and until proven otherwise, self-domestication remains a plausible explanation for our best tendencies. It might explain our worst, too.

Humans are a paradox. Our inner bonobos have a dark, cruel foil. We go beyond prejudice: we dehumanize others, psychologically stripping them of full personhood. That allows us to harm, torture, and kill without empathy. Dehumanization bleeds into our syntax, like when former President Trump derided immigrants as “vermin” or when Hutus called Tutsis “cockroaches” in the leadup to the Rwandan genocide. Surprisingly, Hare attributes this sinister side to self-domestication, too. If he’s right, then our parallel evolution with bonobos would have come with a dash of chimpanzee.

Hare thinks our cruelty stems from our willingness to see strangers, especially those who share our social identity, as group mates. That goes beyond the capabilities of a bonobo, dog, or friendly fox. “We can care for them like family members and even sacrifice for them as if they’re kin,” he said. We would do anything—truly anything—to protect them.

But when our groups are threatened, our dehumanizing brains activate. That’s contributed to genocides, anti-refugee policies, over-incarceration, the crisis in Gaza, the ability to willfully ignore all this suffering, and more. It might stymie our climate action, too.

For example, after natural disasters, people who dehumanize the ethnic groups who suffered them are less likely to support humanitarian aid. Climate denialists have also described environmentalists as other than human, calling them “communist watermelons” who are “green on the outside, deep, deep red communist on the inside.” According to one study, this perception that environmentalists imperil their way of life explains why right-wing authoritarians deny climate change.

The threat of dehumanizing outgroups is even more glaring when considering the culprits and victims of the climate crisis. The richest, whitest nations are among those most responsible, while the communities most harmed are Black, Indigenous, displaced, incarcerated, disabled, unhoused, and LGBTQ+—groups that are regularly dehumanized. Many of these frontline communities are pleading for survival, but their cries are likely to go unheeded if the people in power deny their very personhood.

Hare worries that our brutality could take over as climate change becomes increasingly existential. Already, resource scarcity is motivating war. And now, the dying fossil fuel industry is deploying desperate tactics to prolong its last breath, delaying a rapid and just green transition that, for hundreds of thousands of people each year, is a matter of life and death. “The more people feel their survival is threatened, the more they’re capable of being irrational and immoral,” Hare said.

There’s no panacea for dehumanization, but promising solutions have emerged. The most straightforward is forging diverse friendships—for example, experiments have shown that being randomly assigned a college roommate of a different race reduces racial prejudice, improves support for interracial marriage, and leads to more pleasant interactions with new interracial strangers. Diversifying social groups will require more than new friendships; it’ll require structural changes, too, like school integration and combatting redlining. It also helps to think of people as part of the animal kingdom rather than conquerors who dominate it. Maybe, as humanity’s closest living relative, this is where bonobos can help.

André said many of the 30,000 people who visit Lola ya Bonobo each year leave with changed hearts. “They are ready to absorb everything about [bonobos’] kindness, about the way they can make a new world with more love,” she said. She knows firsthand how profound that change can be. “Bonobos taught me a lot about being human. Perhaps the bonobo taught me more about serenity and peace than anyone I ever met.”

But they may not be around for much longer. Bonobos are endangered, and researchers worry they might soon go extinct. The tragic irony is that their story, which started with a rich climate and a peaceful approach to resolving conflict, is ending with violent disputes over the very resources that may have allowed them to become friendly in the first place.

Humans have greedily exploited the Congo for centuries. European imperial interests enslaved its people, seized its rubber, burned its oil, and packed its uranium into the nuclear bombs that killed more than 100,000 people in Nagasaki and Hiroshima. Colonialism’s legacy would later fuel the resentment that led to the Rwandan genocide and the two Congo Wars, during which all parties were accused of looting the region’s natural resources and wealth. The resulting conflict lasts to this day.

Today, over 25 million Congolese people are food insecure, and 60 million—more than half the population—live below the international poverty line. Destitute people in desperate times poach apes and log their habitat just to survive. Political violence directly chips away at primate populations, too. Just last December, two bonobos that Lola ya Bonobo reintroduced to the wild were killed by armed men in an act believed to be linked to the DRC’s presidential election later that month. Centuries of profiteering, exploitation, and war have sent the empathic apes careening toward extinction.

Political power games—not unlike those played by chimpanzees, Samuni said—put us in this bind. Hare agrees: He believes our chimp-like drive to dominate and subjugate underlies everything from climate change to attacks on democracy. If embracing our inner chimpanzee got us here, then maybe channeling our inner bonobo can get us out.

Hare said that if bonobos were in charge, they would use their power to prevent the greatest violence, be it war or climate injustice. De Waal added that they might link arms as one unified species. They might see across party lines to spark the global, collective action needed to establish peace, protect the planet, and preserve their own species.

In saving bonobos, maybe we’d save ourselves, too. Maybe we’d rekindle our inner goodness. They are our better halves, after all. Without that, what else might we lose?

Special Thanks Friends of Bonobos and Lola ya Bonobo sanctuary

This story first appeared in Atmos Volume 9: Kinship with the headline “The Best and the Worst of Us.”

Chimps and Bonobos Reveal the Best and Worst of Us