Words by Aarohi Sheth

photographs by ashish shah

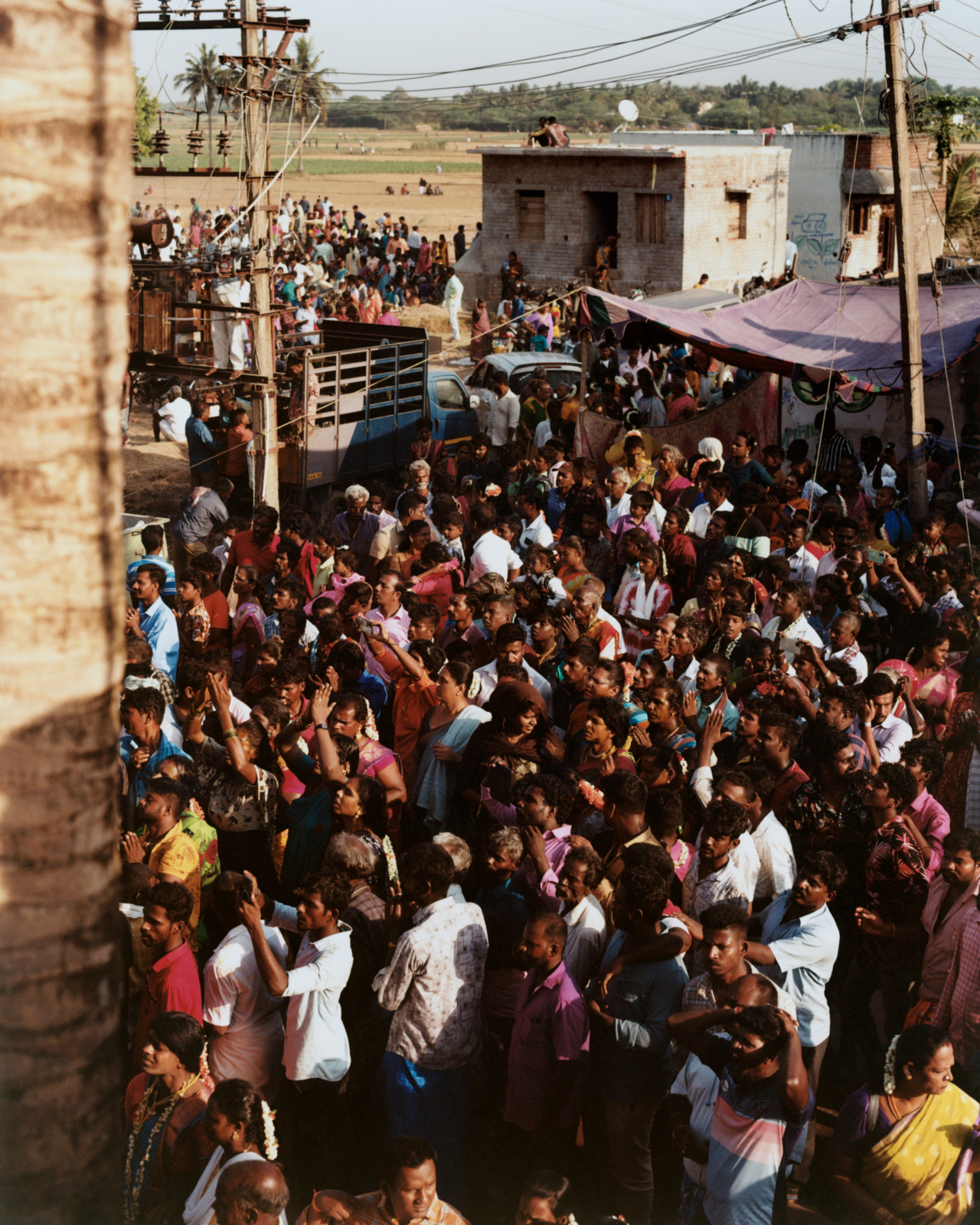

Every year in the month of Chaitra (April/May), the sleepy village of Koovagam comes alive, as thousands of trans women, dripping in gold jewels and sweat, gather to become brides for a day and reenact rituals of marriage, sacrifice, and widowhood.

The 18-day-long affair is known as the Koovagam festival, a trans-celebratory occasion rooted in mythology and Tamil renditions of the Hindu epic, Mahabharata. “It’s beautiful to see my community in such huge numbers,” said Kalki Subramaniam, an activist and artist from Pollachi who has attended Koovagam many times.

Each year, Koovagam takes place in Tamil Nadu, India, at the Koothandavar Temple, which is dedicated to Aravan, or Koothandavar, a character from the Mahabharata. The epic tells the story of the 18-day Kurukshetra War, in which Aravan sacrifices himself to secure victory. Because of his decision, Krishna, the god of love and protection, grants Aravan his wish to marry before dying—with Krishna transforming into a woman, Mohini, and marrying him. Aravan is soon after sacrificed to Kali, the goddess of time, destruction, and death. The day after Aravan’s sacrifice, Mohini, now widowed, grieves him and practices mourning rituals to honor his death.

At the festival, Koovagam-goers mirror these ancient histories.

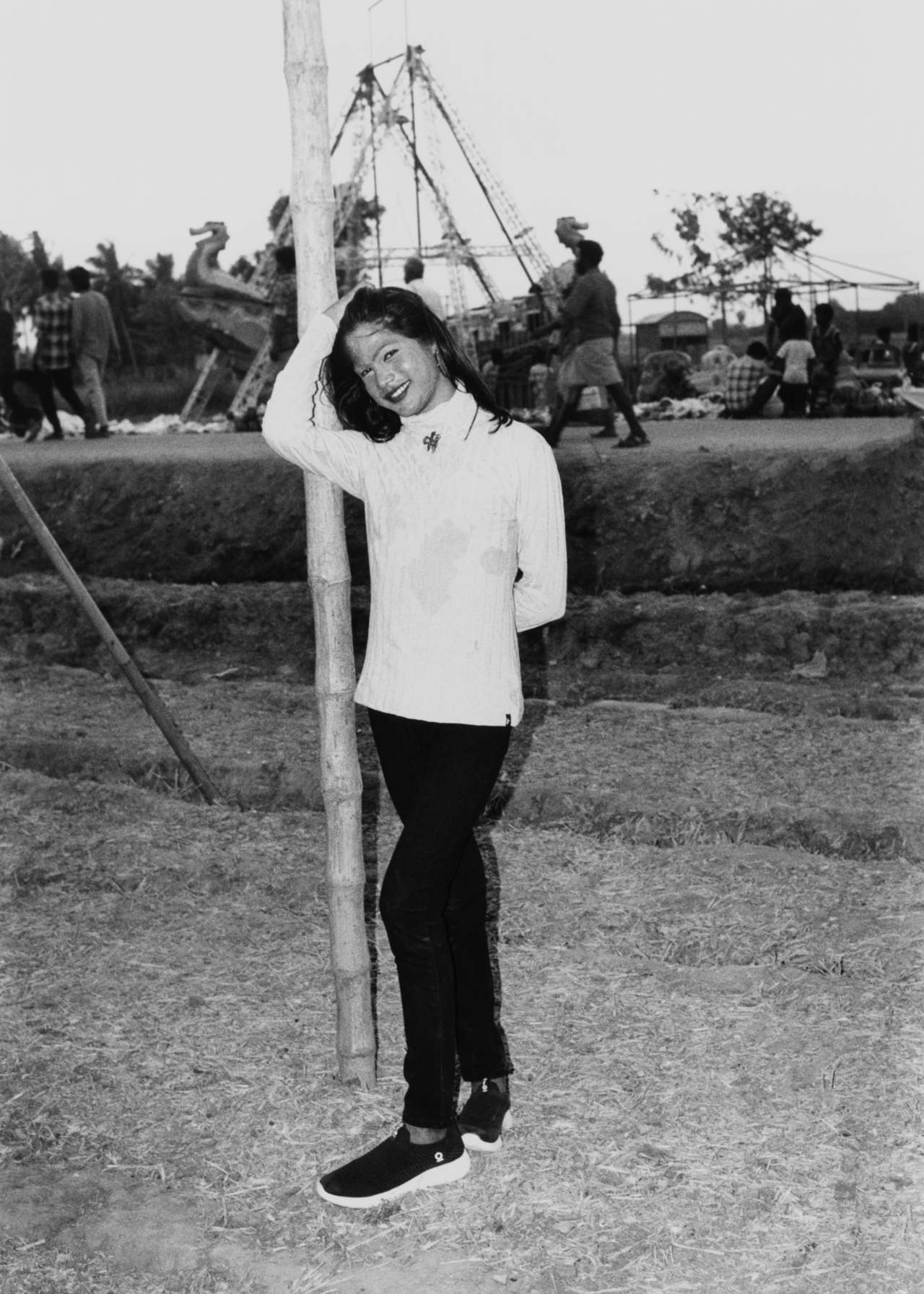

For the first 13 days, Koovagam is full of dancing and singing as the Miss Koovagam beauty pageant takes place. Photographer Ashish Shah, who documented this year’s Koovagam festival, ran into the Miss Koovagam first runner-up at his hotel following the pageant. She only had 10 minutes to get photographed before her trek home, and “she had so much pride, it was beautiful,” said Shah. “For that hours-long drive—in [intense] heat, no less—she stayed in her makeup and winning look.”

The trans and queer communities in India have long faced discrimination, especially in more rural and conservative areas, despite the country’s trans community being one of the oldest in the world. Spaces like Koovagam remind the community—as well as outsiders—that not only is a world where queer and trans folks stand together for their liberation possible, it already exists. And it’s staying. But these events are at risk—not just because of violent laws and legislation that fall drastically short of protecting queer and trans people, but also because of the ever-growing threat of the climate crisis. In fact, temperatures at this year’s Koovagam stayed at a boiling 105 degrees Fahrenheit throughout the almost three weeks of festivities.

Historically, Koovagam has brought many positive changes to the lives of trans people in India. Festival participants engage in sex, for instance, as men from the villages in and around throng to the festival. And in recent years, NGOs and other organizations have attended the festival to distribute condoms, raise awareness about the prevention and treatment of HIV/AIDS, and run mobile testing centers. “Koovagam ignited social change, brought more awareness of trans issues to the public as well as to the government, policymakers, and media,” said Subramaniam.

Koovagam, and trans-celebratory spaces like it, are necessary because they center trans joy against an otherwise volatile political backdrop. On the 14th day of the festival, the full moon day, the women gather from daybreak at the temple, dressed as Mohini. They drape themselves in sarees, wear new bangles on their hennaed wrists, and wrap floral garlands in their braids for their marriage to Aravan. They sit in the nearby fields they sleep on, using their phones as mirrors as they do their bridal makeup.

“Queer and trans people are nature, so being in the natural world and connecting to the Earth is quite healing.”

“This festival is absolutely queer and trans joy, but more than that, it’s queer integration,” said Nisha Venkat, a South Indian, Dubai-raised podcast producer and activist who organizes events for Satrang, a Los Angeles-based organization serving LGBTQ+ South Asian folks. “These women often live on the fringes of society, but Koovagam specifically centers their existence and experiences and allows them to partake in life milestones—many of which are important to some, not important to others, but regardless, to carve out the opportunity to participate in them is beautiful.”

For Subramaniam, Koovagam is “a true place of liberation,” especially before she came out and transitioned as the festival was “completely different” from what she experienced in her day-to-day life. “Koovagam is not everyday life, there’s no doubt about it,” she said. “So, it’s very exciting that it happens for just a few days out of the whole year.”

Priests officiate the marriage ceremonies between the women and Aravan-proxies, tying thaalis around the women’s necks and dotting kumkum powder on their foreheads. The women rejoice in their newlywed statuses for the rest of the day. “It seemed like this festival was not only validating for the women. It brought a whole different kind of happiness to them—one that can only happen by celebrating together,” said Shah. “Everyone had a smile on their faces. They all wanted to get photographed and have their looks documented. It felt like they wanted more people to know about the festival and see them. It was their time to shine.”

On Koovagam’s 16th day, however, the celebrations end, as the women become widows. They change into white sarees, remove their thaalis, and break their bangles, signaling the start of their joint widowhood. Together, the women cry to the skies and mourn Aravan’s death. And there’s a clear connection between the tears Koovagam-goers shed at the festival to their real-life traumas and difficulties. They’re not just collectively lamenting Aravan’s death, but protesting against the discrimination and abuse they often face in society.

In 2014, India’s Supreme Court recognized the right to choose gender, and yet, homosexuality wasn’t decriminalized until 2018 after more than two decades of court cases, protests, and resistance movements. Then, in 2019, the Parliament of India passed the Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Act which would supposedly provide trans folks with the protection of rights and welfare. However, it was met with vehement protests by many transgender people and activists in India as its original version involved the criminalization of begging and required trans folks to prove that they underwent sex reassignment surgery to receive a proper identity certificate. The act has also been criticized for inflicting less punishment for crimes against transgender people compared to those against cisgender people.

“This festival is absolutely queer and trans joy, but more than that, it’s queer integration.”

Even the reenactment of marriage at Koovagam parallels the challenges of LGBTQ+ folks fighting to gain equal marriage rights in India. For many women, Koovagam is a space to imagine, a vessel for experiences they may never get in real life. Shah, for example, said that growing up in India, he saw many trans women go through “extremely difficult lives.” He added: “Why can’t the transgender or gay community’s lives be like [Koovagam] daily? Why do these trans women just get one or two ‘special’ days to fully be themselves?”

Subramaniam said she could only do the mourning ritual at Koovagam once as it was “psychologically painful” to get married one day and be a widow the next. Her friends, however, have done this reenactment multiple times. “The widowhood ritual is as aspirational as it is cathartic as it is celebratory,” said Venkat. “[The participants] are acting out an entire life within a couple of days—perhaps a life that they aspire, or aspired, to have.”

The festival also revolves around nature, as its most important rituals, such as the marriage day, take place under the glow of a full moon. Before their wedding night, the women often sleep together on plastic sheets in the surrounding rice fields and dirt pathways. Koovagam is one of the few occasions when the transgender community can flaunt their beauty and gender identity in public without facing persecution or censorship.

Not only is the festival a political statement, but a cultural one as well. Therefore, the visibility of the festival is central to its identity. “Events like Koovagam need to happen,” said Pri, a manager from Chennai now residing in Canada. “There should be this sort of visibility, so people who are closeted and don’t want to be or those who don’t feel the courage to be themselves, see that another life and community is possible.”

But trans spaces like Koovagam, which often take place at least partly outdoors, are at risk—as being outside amid India’s sweltering temperatures can result in heat exhaustion, heat stroke, dehydration, and other heat-related illnesses. Currently, India is facing its longest heatwave on record. Parts of the country have been experiencing extreme heat since mid-May, as temperatures hover between 113 and 122 degrees F in several cities. And this isn’t new. In 2023, India experienced extreme weather events, including heat waves, droughts, severe rainfall, and flash floods, 86% of the days in the first nine months of the year. Nearly 3,000 people died, almost two million hectares of crops were ruined, 80,000 homes were destroyed, and more than 92,000 animals were killed.

“Koovagam is where we celebrate our talents and beauty and what we contribute to society. We talk about our future as a community, and why we matter—why trans lives matter.”

Rising temperatures and the larger climate crisis endanger vulnerable populations, like trans folks, disproportionately, as those who are already at risk of or currently experiencing homelessness, food insecurity, health injustice, and abuse, are more likely to face the repercussions of extreme weather events. “Climate change is a direct threat to the transgender community, many people are becoming homeless,” Subramaniam said. “I need the government to pay attention and implement policies that protect the community from climate change.”

And it’s no coincidence that trans-celebratory events like Koovagam take place outside.“There’s something about outdoor spaces that are very liberating,” said Venkat, who most recently organized an outdoor gardening day for Satrang community members. “You’re quite literally out of the closet and in a space that can’t be controlled. Though being visibly queer opens you up to public scrutiny, events like Koovagam present safer alternatives.”

Occasions like Koovagam also present opportunities to be one with nature, which can be particularly meaningful for communities that have long been deemed unnatural. “Queer and trans people are nature, so being in the natural world and connecting to the Earth is quite healing,” said Venkat. That’s why climate change and extreme weather events, including rising temperatures, pose an existential threat to Koovagam and the women who rely on the event for spiritual ease and community-building. For now, though, the festival persists.

Koovagam lies between the intersections of nature, religion, gender, and sexuality. The festival is an exercise in space- and meaning-making—a place for communal energy exchange, from joy to pain, and desire to love. “[Trans women] are mostly silenced in spaces, but at Koovagam, we are gathered together by the thousands,” said Subramaniam. “The festival isn’t necessarily a rally, but a collective voice. At its core, Koovagam is where we celebrate our talents and beauty and what we contribute to society. We talk about our future as a community, and why we matter—why trans lives matter.”

When the festival ends, the village of Koovagam is littered with leftover decorations, condoms, sandals, and broken bangles. Once again, it quietens and becomes empty. “Things go back to normal. There was no sign of anyone,” said Shah.

But the liberation of trans women and people exists—and has existed—far beyond the festival grounds. “Tamil Nadu has been the source of liberation for all trans people in India,” said Subramaniam. “We have been at the forefront of this movement and though growing up was difficult for many of us, trans women are fighters. We’ve established our identities in this misunderstanding world. We’ve found our place—in and outside of Koovagam.”

Trans Joy Persists Amid India’s Growing Climate Crisis