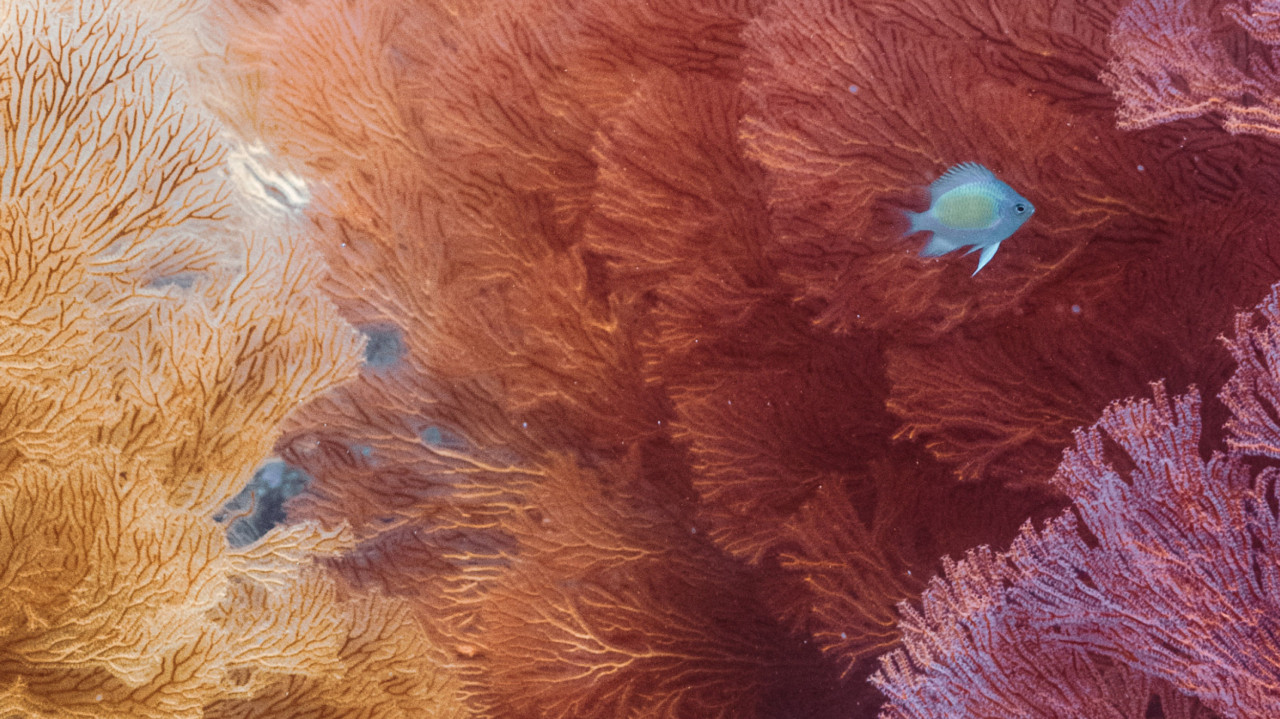

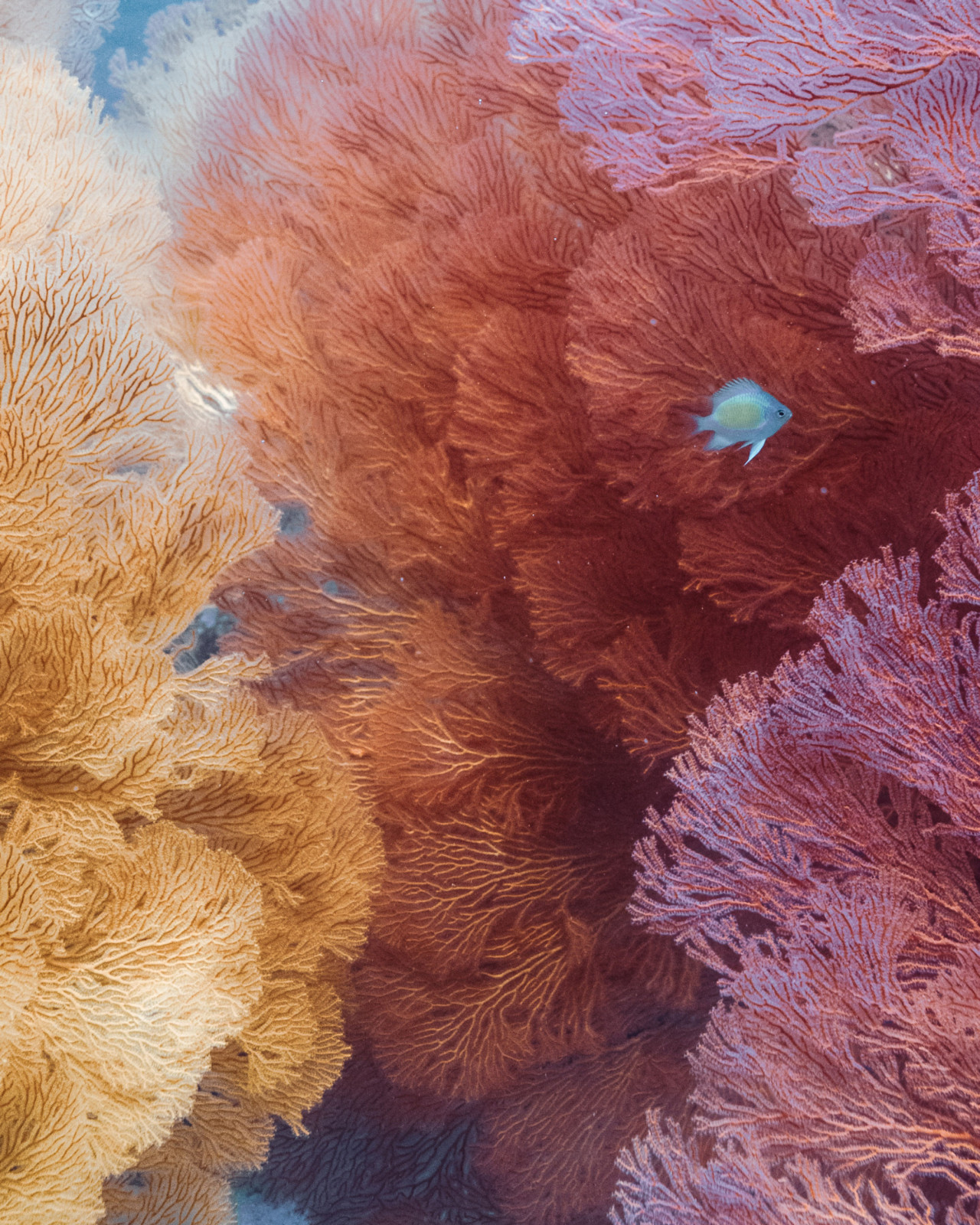

Photograph by Zoe Lower / Kogia

words by miranda green

As the theory of evolution tells us, early ancestors of today’s mammals emerged out of the oceans roughly 370 million years ago. Yet today, we’ve mapped less than one-third of the seafloor.

Where our terrestrial biology has limited our ability to physically explore the depths of our blue planet, decades of innovations have helped.

The development of sonar in the early 1900s to detect glaciers and then enemy submarines allowed oceanographers to create some of the first maps of the ocean floor. Jacques-Yves Cousteau’s invention of the Aqua Lung in the ‘40s enabled adventurers to spend extended periods of time underwater. A decade later, the first remotely operated vessel let scientists chart ocean depths humans couldn’t otherwise survive. And in 2011, Japanese researchers were the first to discover rare earth minerals in the deep-sea mud of the Pacific Ocean.

Now, the United States government wants to use those advancements and more to give companies streamlined approval to strip the ocean for cobalt, copper, manganese, and nickel.

The Trump administration last week announced it would accelerate the permitting process for companies looking to mine the deep sea around American waters. The finalized rule follows last April’s executive order directing various agencies to expedite the review and issuance of seabed mineral exploration licenses and commercial recovery permits. To that end, U.S. agencies tasked with studying and permitting ocean development are moving ahead with vetting approvals for deep-sea mining exploration in key corridors.

Last June, the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management announced it was initiating the process to lease deep-sea mining plots off American Samoa, a group of South Pacific islands roughly 2,500 miles south of Hawai’i. In November, the agency published a notice to gauge interest should mining be opened off the Northern Mariana Islands, located between Hawai’i and the Philippines.

The decision to proceed with extracting the ocean floor’s mineral riches mirrors similar pushes by the White House to obtain other natural resources, from oil and coal to uranium, all while attempting to remove any protections that might prohibit such extraction. The behavior follows the concept of Christian dominionism: that God gave us these earthly niceties, so we are right in using them—even to oblivion.

John Rockefeller once argued, as he built his oil empire, “I believe the power to make money is a gift from God.”

Trump has taken note.

Since returning to office, the president:

-Introduced the “Unleashing American Energy” executive order to expand fossil fuel extraction;

-Removed national monument protections that limited energy exploration;

-Ordered the removal of protections for the 500,000-square-mile Pacific Islands Heritage National Marine Monument, opened it up for commercial fishing, and called for a review of all other marine monuments;

-Ousted Venezuela’s sitting president and began selling off the country’s oil reserves; and

-Led an unsuccessful campaign to take over Greenland, in part for its rare earth minerals.

The deep sea is considered the oldest and largest biome on Earth.

It’s home to volcanic underwater mountain ranges known as seamounts, valleys like the seven-mile-deep Mariana Trench, and rich biodiversity that’s still being discovered, such as bright orange, frilled sea pens and glowing worms. The deep sea produces half of the world’s oxygen and absorbs about 30% of CO2 released into the atmosphere.

Also on the ocean floor lie bumpy, egg-shaped rocks bursting with minerality. Called polymetallic or manganese nodules, they form over millions of years as minerals accumulate around a central core. The nodules contain high concentrations of elements and minerals used in cell phones, laptops, and fighter jets—as well as necessary ingredients in EV batteries and renewable energy tech now driving the world’s clean energy transition.

China currently has the highest stockpile of rare earth minerals, which is where the U.S. mostly sources from. The White House hopes to change that dynamic by reaping the benefits from its own waters surrounding formerly colonized islands.

There are several eager companies lined up for the chance to mine these nodules, but there has yet to be any commercial deep-sea mining. And that makes it hard to say how drilling thousands of meters down on the ocean floor will go.

Environmentally, there’s grave concern. A study released Monday by a cohort of international scientists found that there is more biodiversity on the ocean floor than previously believed. After cataloging marine life and testing potential mining impacts in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone, between Mexico and Hawai’i, researchers found that areas directly disturbed by mining equipment experienced a 37% decline in animal numbers and a 32% reduction in species diversity.

A separate study published in November found that waste from mining could harm more than half of the zooplankton in a vital region called the “twilight zone,” which could put larger species higher up on the food chain at risk.

There are some ironies that the same administration opposing offshore wind—allegedly because of unverified concerns that such installations lead to the deaths of right whales—is now promoting a new form of unvetted, potentially harmful extraction in an effort to mine for a key ingredient in renewable technology.

There have been strides to clamp down on illegal deep-sea mining in international waters. The High Seas Treaty—the world’s first legally binding agreement to protect marine life—took effect last month, but the U.S. has not ratified it.

Locally, island-nation residents who could bear witness to these deep-sea mining efforts are strongly opposed.

“From the very beginning the process was colonial,” Sheila Babauta, an Indigenous Chamorro-Pohnpeian resident of the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands, told Grist. “Our political leadership was not consulted before the [proposal] was issued. This industry and this proposition is being imposed on us—it’s not something that came from us.”

There’s a lot we don’t know.

We don’t know how deep-sea mining will impact the ocean floor, the flora and fauna that live there, and the people who live around it. Economically, we don’t know how much it will cost (though estimates don’t seem favorable).

Like all things climate, there are rarely perfect solutions. To build out clean energy infrastructure, we need rare earth minerals. So to some, the future does lie in the deep.

The White House Wants to Mine the Oldest Biome on Earth