WORDS BY RUSSELL REED

photographs by marie jacquemin

One too-hot morning at the Long Beach flea market last summer, I had nearly thrown in the towel when something caught my eye. Hidden in a stack of yellowing treasures was my best find yet: a promotional poster for the 1992 Earth Summit in Rio, the precursor to the United Nations climate negotiations.

Designed by Robert Rauschenberg, it features a collage of hidden symbols overlaid in contrasting splashes of color: Atlas kneeling in his perpetual struggle under the weight of the world, the dark-orange silhouette of a newborn child sheltered by the great umbrella the international climate community was meant to be. Across the top, it reads: “I PLEDGE TO MAKE THE EARTH A SECURE AND HOSPITABLE HOME FOR PRESENT AND FUTURE GENERATIONS.” Three decades, 28 U.N. climate negotiations, and nearly 0.7 degrees Celsius of global heating later, however, it’s clear that this promise has not been kept.

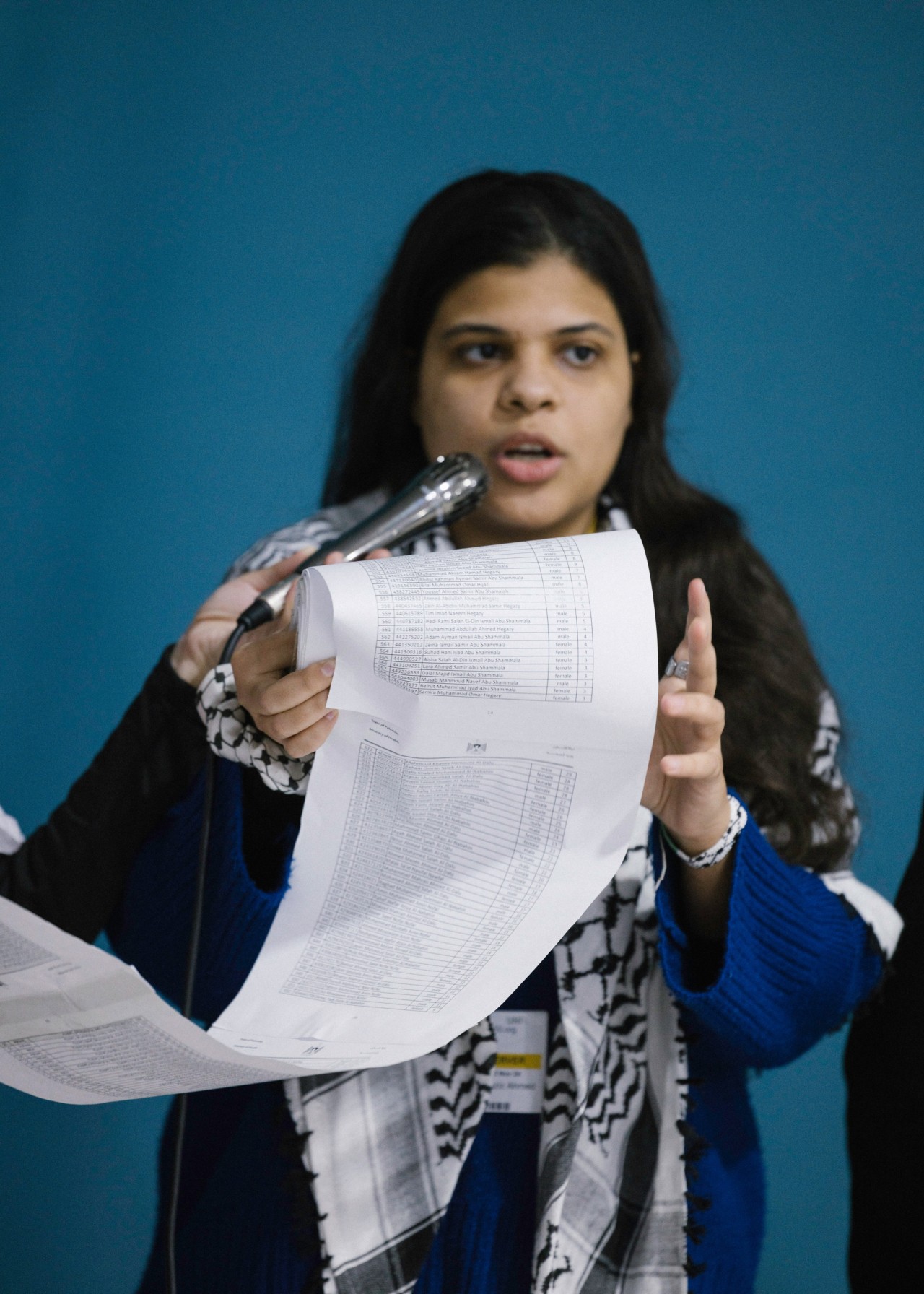

Rio’s “future generations” have since grown up as natives of the climate crisis, only ever knowing a planet on fire. Maybe that’s why young people are so determined to realize a better world beyond it. Last week, we showed up to COP29 in Baku, Azerbaijan in large numbers, fighting for a future that is less certain than ever. We are no longer agentless symbols of impending Armageddon. As the heirs of the Earth that delegates are negotiating over here, we know our voices must be heard. That’s why last week, we united a diverse international coalition calling for a Universal NDC Youth Clause. We are calling on governments to commit to engaging us as true partners in their new climate action plans due in February. But when we speak, will world leaders listen?

If history has a say, the answer is a resounding no. Just ask Mexican Otomi-Toltec climate justice activist Xiye Bastida. She can trace the origins of her activism—and her life itself—to the Rio Earth Summit, where her parents first met, then in their 20s and part of a much smaller community of youth climate activists. More than three decades later, she jokes that she sees her father more often at multilateral negotiations than she does at home.

While they met in Rio, her mother didn’t fall in love until the following year in Quito. She was serving as his translator, relaying his message on the value of Indigenous knowledge to a room of foreign negotiators. In the middle of his address, he paused and left the room. Alone, she translated his words: “You are not ready to hear my message.” She then followed him out the door.

At COP26 in Glasgow, Bastida’s own opportunity came to close out the World Leaders Summit. After remarks from heads of state Emmanuel Macron and Narendra Modi, Bastida—then 19 years old—approached the podium for her speech. By the time she began, however, the audience had already cleared out. Still, she addressed the empty room.

Later that night, she sought comfort from her father at an Indigenous leaders dinner, devastated by the experience. He consoled her, reminding her that she had done the job she came to do. It reflected a shift from his own time as a young activist in these same spaces; today, youth are speaking regardless. “It is their job to listen,” he told her.

This type of disregard is especially evident toward “young Indigenous people, Afro-descendants, transgender people, young people with disabilities,” and beyond, said transgender Indigenous activist Jâre Aikyry. As the co-executive director of Engajamundo, the largest youth movement in Brazil, he is intimately aware of the many voices that will never gain access to these decision-making spaces at all. “They don’t even remember that we exist,” he said.

Even when young people are invited to the negotiating room, Umazi Mvurya, an Indigenous advocate and conservationist from Kenya, struggles to see how decision-makers have taken their perspectives into account.

“We bring pressure,” Mvurya said. “But are our ways of bringing pressure working? I bring pressure into every room I enter, and I am recognized for challenging these longstanding views. But the result is that I get added to more events—for what reason? If it isn’t resulting in real changes, in real actions, what is the point?”

Those dynamics remained unchanged at this year’s COP. Even for the small number of youth activists with access to COP29’s infamously exclusive “Blue Zone” where the negotiations occur, complaints of exclusion, silencing, and tokenization remain commonplace. At the largest action of the convening so far, activists were restricted from singing or chanting; they could only hum. So hum they did, in great numbers, with signs reading “SILENCED” taped over their mouths.

At COP29, I have laughed, cried, and danced with other young activists. There are moments of breathless rage, eyes puffy from tears and exhaustion. But equally, there are moments of joy and connection—the kind that reminds us that the work we do in our own communities is not in isolation, but within a global movement of remarkable size and scale. And it is growing every day.

“Young people have the power to speak from the heart and to the heart, a skill which is often lost among older generations.”

“Young people have the power to speak from the heart and to the heart, a skill which is often lost among older generations,” said climate activist and Fridays For Future organizer Luisa Neubauer.

Our presence is not simply abnormal, it is powerful, and it reflects the distinctive humanity of the new era of environmentalism. While the environmental movement of the past has failed, for decades, to gain the traction needed to curb the climate crisis, our fight for climate justice has brought more people to the streets in protest than ever before. We are building the largest social movement in history, fighting not just for survival, but for a just and equitable future for all.

The call for increased youth inclusion does not stem from ego; we do not wish to be handed the reins to combat this crisis alone. My environmental worldview has been shaped foundationally by scholars, scientists, and activists who have been in this fight since long before I was born. Bastida’s activism is inseparable from that of her parents. As Mvurya strives to protect and restore her community’s ancestral land in the coastal forests of the Mijikenda, it is her elders’ generational wisdom that guides her conservation efforts. Intergenerational collaboration is an everyday practice for many, building the kinds of effective and equitable solutions we desperately need to effectively confront the climate crisis. Now, we want to see that reflected on the international stage.

As young people, we carry a coherent, articulate, and inspiring vision for the kind of future we want to live in. But it is together with the powers that be, not in isolation, that we will build it. The Universal NDC Youth Clause that I helped launch last week in collaboration with a coalition of youth organizers including Aikyry, Mvurya, and Neubauer is a step in that direction, and it’s gaining traction. On Monday, November 18, Ed Miliband, U.K. Secretary of State for Energy Security and Net Zero, joined me on stage to become the first country to make the pledge. That commitment reflects increasing recognition that youth inclusion may just be the missing link needed to unlock effective climate action.

“If you think like a young person, if you think like future generations,” Miliband said, “it leads you to ambition for action … and to justice between the generations.”

For all of us alive today, young and old, our shared legacy will be the world we leave behind. Will we step up to this challenge together, or fail in isolation?

Editor’s note: This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

The Kids Are Crying at the Conference of Parties