Words by K.O.

artwork by Anthony Gerace

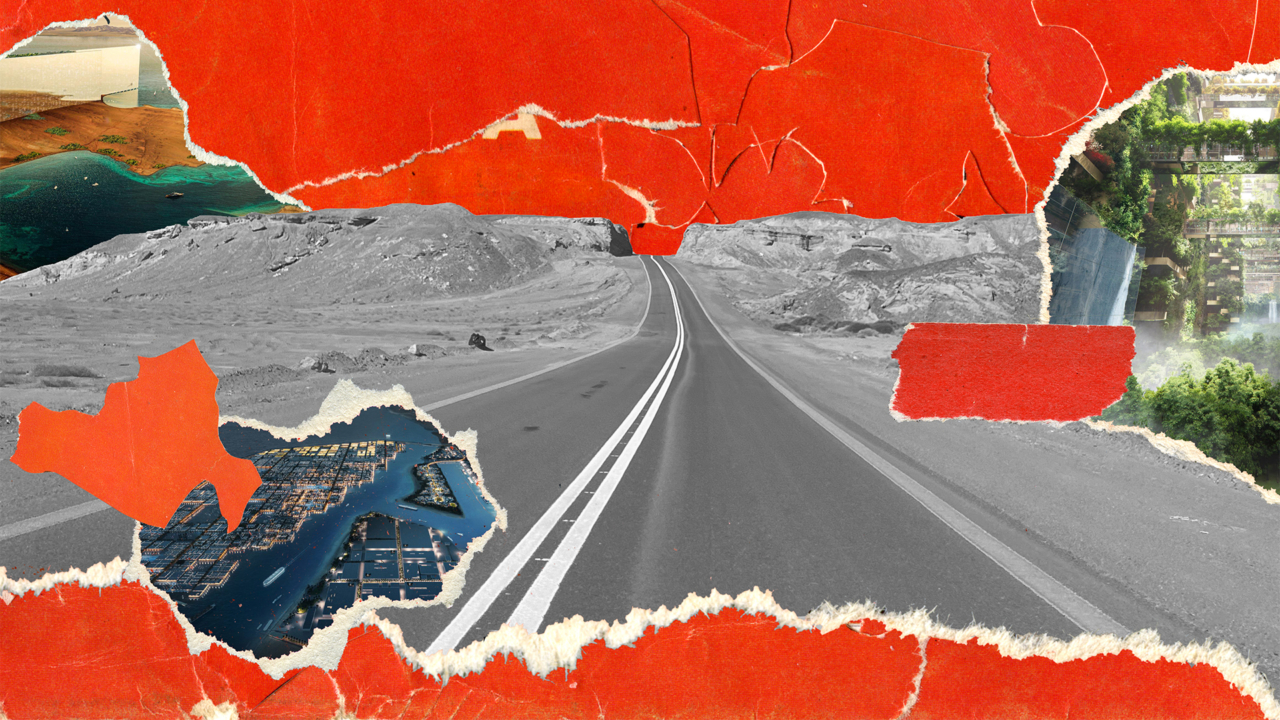

Near my hometown of Tabuk, not far from the Red Sea in northwestern Saudi Arabia, the construction of a new mega-city is well underway.

Promising to reimagine what a climate-resilient city of the future could look like, the project has been dubbed “NEOM,” referencing the Ancient Greek prefix “neo,” meaning new. The “m” refers to “mustaqbal,” an Arabic word for “future.” The mega-city—an initiative driven by crown prince Mohammed bin Salman—will contain 10 separate regions, including The Line, a 170-kilometer city that will house nine million people in two parallel 500-meter-high linear skyscrapers built 200 meters apart. NEOM will also reportedly be powered entirely by renewable energy, and developers allege that 95% of local land and sea will be conserved and protected.

Since its announcement in 2017, however, the construction of NEOM has undermined the very promises it was supposedly founded on. Like many cities in the Gulf, NEOM is built on the exploitation of migrant labor, and reinforces a hierarchy of workers based on practice and citizenship wherein white Western nationals are the best paid and most senior. Meanwhile, local communities that have, for generations, lived on the land NEOM is being built on have been offered payment to uproot their lives and move to other villages or even the region’s capital. Those who refused the compensation were threatened with eviction, or worse, murder. This was the fate of Abdulrahim Alhuwaiti in 2020.

While it’s true NEOM provides exclusive education and employment opportunities for Tabuk residents, they come at the cost of numerous violations — and it is also rapidly changing the cultural, ecological, and geographical landscapes of the region. It’s why many of us are constantly grappling with questions around why and for whom this city is being built.

On a road trip along the coast last December, I revisited some of the coastal towns where NEOM is being built; locations I’ve visited with my family regularly since childhood. These are snippets from what I saw, and what I felt.

8:15 AM

To love Tabuk is to love the sea.

This ancient province and oasis is located in the northwest of Saudi Arabia and is home to coastal towns that overlook the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aqaba. Its capital, which holds the same name, is at the center of the region’s brilliantly diverse ecosystems, including endless dunes, snowy mountains, and golden beaches. We call the city, تبوك الورد, or Tabuk of Flowers, for its rich history of agriculture and farming practices. But I’m obviously biased. Tabuk is the only home I know and yearn for.

Many of us are constantly grappling with questions around why and for whom this city is being built.

The Municipality of Tabuk’s website traces the province’s name to the Latin word Tabu, which means “excluded” as its location isolated it from the Levant in the north and separated it from the rest of the Arabian Peninsula in the south. Whether the history of the name is accurate or not, semantics was all I was thinking about as my dad, my youngest sibling, and I were driving west to Tayyib-Ism one morning, a couple of hours after sunrise.

The drive to the coast wasn’t something new to us—we know the road and the rock formations that border it very well. This time, however, there was a foreign word on every kilometer road sign: NEOM.

9:20 AM

The first stop we made on the way to Tayyib-Ism was Gayal.

The last time we had visited Gayal’s beach was in the summer of 2020 right after COVID-induced lockdown rules were lifted—all we wanted was to swim until sunset and pick up singari fish to eat by the water before Isha prayer. At that time, NEOM was a mere concept. It existed only as an airport and some residential units. No one in Tabuk actually knew what it would look like except for the very limited pictures and footage released on national television and social media by employees or journalists. Yet, it was on everyone’s minds.

My uncle couldn’t get us sangari fish from his favorite spot that night, saying all local businesses are closed in preparation for “the new project.” Construction was already underway. But NEOM wasn’t just daunting because both the developers and local government had ordered the closure of businesses—or, indeed, because of my uncle’s failure to secure sangari fish. NEOM was rapidly introducing new changes to Tabuk’s ecosystems and local communities that would alter the region’s social fabric forever.

9:50 AM

Gayal beach remained like it has always been: glistening water and endless sand marked with our footsteps and car’s tires. But now, according to a new road sign marking yet another construction site, it is now called “NEOM Sports Beach.”

In late 2017, on the first day of the Future Investment Initiative conference in Riyadh, NEOM was launched by the Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman (MBS). Before his speech, a video promoting the mission of this new mega-city played on a huge screen in front of the conference attendees. As usual, the narrator had a British accent, and stated that NEOM will extend across “over 26,000 square kilometers of land [in] an ideal location.” It’ll also be “the world’s most ambitious project, a destination of the future, a vision that’s becoming reality,” he added. Four years later, in 2021, The Line was announced as a city in NEOM. Again, MBS began the announcement with a promotional video that claimed all major cities “prioritized machines, cars, and factories over people.” But this is neither sustainable, nor does it improve people’s quality of life. And that’s where The Line comes in—it’ll be the first city in the world “with zero cars, zero streets, and zero carbon emissions,” according to the video. In other words: The Line will redefine what a contemporary city looks like within the context of climate change and international trade.

But with both NEOM and The Line, Tabuk is forgotten.

Tabuk, the city, the province, the tribes that have lived there for centuries, aren’t named. In fact, “the land” is only referenced by MBS as a source to be extracted, used, and built on. It’s never mentioned as it relates to the people who have been living on and with it for generations. So then, who is this hub, this mega-city, built for? Who does it exclude, and who does it displace?

10:30 AM

Even in the middle of the water, the sight of construction is inescapable.

We always go to the same secluded beach in Gayal, marked only by an abandoned mansion nearby. Today, the pathway leading down to the beach is no longer as easily accessible. Both sides of the road are marked by fences and signs indicating construction sites for The Line, which are frequented by workers in neon vests and trucks. While some of these sites were previously unoccupied, many were home to local houses, schools, and markets in Gayal as well as neighboring areas in Tabuk—including Abdulrahim Alhuwaiti’s home in Alkhuraybah.

In 2020, Abdulrahim Alhuwaiti released a series of videos on YouTube that later circulated on social media platforms Twitter and Instagram. In one video, he starts by introducing his name and village, and then flips the camera to document his surroundings: police cars and officers circling his home. In following videos, he explains that they’re here to take measurements of their houses to aid construction for The Line, which in effect will forcefully displace them elsewhere in Tabuk. He also states the full names of officers who have been coming to his house on a regular basis, asking for him to sign on a document that shows his approval to move out in exchange for compensation. Alhuwaiti appears perplexed, asking: “How does NEOM develop [opportunities for local] citizens by getting them out of their land?”

He’s not the only person protesting. Other families are seen in his videos speaking with police officers. But the police don’t appear to be listening.

Shortly before his murder in April of 2020, he released a video stating that the tactics used by the police to forcibly remove local communities from their homes in Tabuk are nothing short of terrorism. In Alhuwaiti’s eyes, it is crucial he stays in his home and rejects any form of compensation. He also predicts his death, saying that the police will do to him what other Egyptian officers have already done on the other side of the sea: kill someone and plant a gun to show them guilty of resistance. This is exactly what happened—after his video was released, Alhuwaiti was shot at his home only to be framed as a criminal who initiated the shooting, according to an official statement released by the Presidency of State Security.

No future is worth building if it costs the loss of a singular life.

11:45 AM

Before driving to Tayyib-Ism, my dad drove more in-land to visit Asaila, where he became a teacher at an elementary school after graduating from Tabuk’s College for Teachers. The school where he taught was gone. The homes surrounding it were gone. The palm tree farms were also gone. Nothing looked the same to him. We all knew why, but no one could bring themselves to name what caused this scale of disappearance. There was an underlying fear that even thinking this was wrong, and could lead to the same fate of Alhuwaiti—or the over 20 imprisoned people from his tribe, al-Huwaitat.

What remains are palm trees, abandoned and fenced. Some of them were uprooted and laid inside large wooden containers marked by a sign that read, NATIVE PALM TREES, TRANSPLANTING & VEGETATION: PHASE 1. As if the farmers who have lived here and tended to these palm trees for generations didn’t know what they were doing—so, some “conservation” leaders had to be summoned to save the day.

By midday, my dad had driven to Al Bad’ to reach it by Dhuhr prayer. He stopped by a drive-through cafe in a gas station for lunch. There were a few kids getting snacks from the market nearby; they wore backpacks and had probably just finished school before walking home. One of them was in the same line as us, waiting to order food. The boy greeted my dad and, as most introductions go back home, they started talking about their tribal affiliations or where they were from in Saudi. His family was from Asaila, he said. Not long ago they moved, alongside other families, to Al Bad’. The only thing remaining in their hometown were the few palm trees his dad had been taking care of.

2:30 PM

After many stops, we finally arrived in Tayyib-Ism.

Before entering the town, the security officer at the gate asked us to drive back. Access to this area requires a permit now as it has become a protected tourist attraction and can only be seen through organized trips. The construction of NEOM had promised to improve tourism and education in Saudi, creating and implementing opportunities exclusively for Tabuk residents like scholarships in Saudi and abroad, employment opportunities and career counseling services, and other professional and entrepreneurship programs.

The history of the name, Tabuk, is both long and disputed—but today, it feels as though it carries some truth. NEOM promises building the first step to more liveable, environment-friendly, and sustainable cities that can persevere against climate change. But the reality is an infrastructure of exclusion that continues to separate Tabuk from everything its people know it to be.

If the ambitious future NEOM promises has its roots in forcefully excluding, displacing, and even killing the people that the mega-city is supposed to serve, is it a future worth building? No future is worth building if it costs the loss of a singular life.

Editor’s Note: This article has been published under a pseudonym for fear of persecution.

NEOM Is a City of the Future. The Land is the Cost.