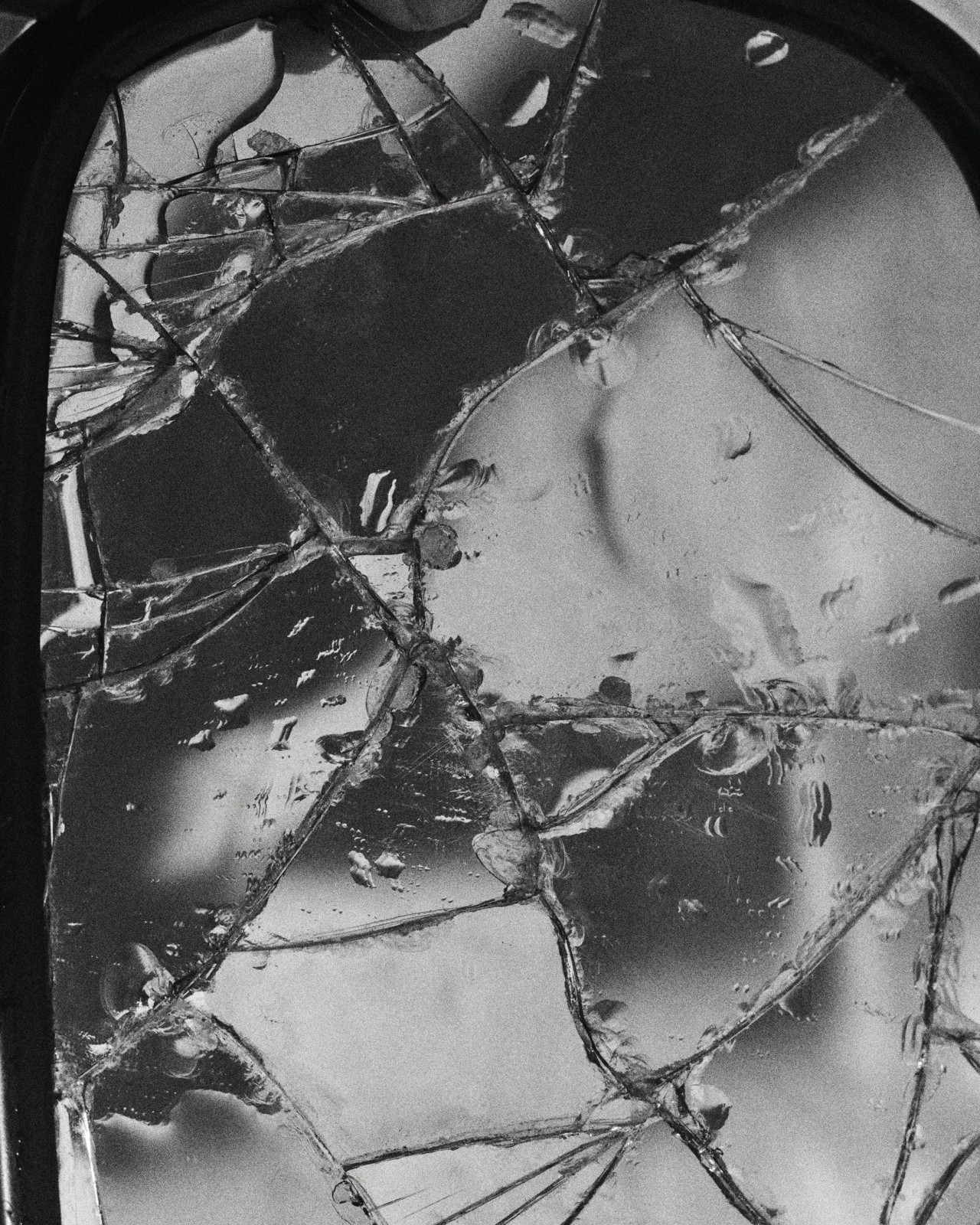

Photograph by Jason Hetherington / Trunk Archive

Words by Rabbi Elliot Kukla

Elliot Kukla is a rabbi, author, and activist who provides spiritual care to the grieving, dying, ill or disabled. He is also a member of Rabbis for Ceasefire. This Points of View article reflects his opinions, not necessarily those of Atmos.

I didn’t grow up learning Torah, Hebrew, or the holidays of the Jewish year. But I did learn Jewish fear.

My grandfather Max was abducted by Nazis on a Brussels street corner in 1942. No one in my family ever heard from him again, but his absence continued to shape my life generations later. I grew up in tranquil Toronto in the 1980s, worried that my family would be rounded up in another Nazi Holocaust. As an adult, I became a rabbi who cares for the bereaved, and I learned that I’m not alone in this persistent fear. Many of the people I serve were taught to fear antisemitism and be prepared to flee, even if they grew up in calm times and relatively safe places.

Unsurprisingly, this past year of death and destruction has brought inherited Jewish fears to the surface. As we approach the first anniversary of October 7th, there’s a battle raging about what meaning to make of these reawakened memories. For me, and for much of my community, the suffering of the Jewish past ignites empathy for Palestinian losses today, leading us to protest for a ceasefire, and an arms embargo of Israel. For others, the Holocaust has exactly the opposite meaning, and is used to justify escalating Israeli violence in order to bolster a Jewish sense of safety.

Haim Bresheeth, a child of Auschwitz survivors, co-founded the Jewish Network for Palestine in Britain. JNP is a group of descendants of Holocaust survivors that has staged a number of rallies for a ceasefire this year, attracting thousands of protestors. Here in the U.S., Jewish Voice for Peace released a statement on Holocaust Remembrance Day, authored by the descendants of survivors, saying: “We are not alone in our trauma, and we have a collective duty to prevent others from experiencing similar harm.”

In stark contrast to this, back in October, U.S. President Joe Biden compared the attacks of 10/7 to the Holocaust: “It has brought to the surface painful memories and scars left by a millennia of antisemitism and the genocide of the Jewish people. The world watched then, it knew, and the world did nothing. We will not stand by and do nothing again.” These words helped set into place a rhetorical framework for comparing Hamas militants to Nazis, which has been repeated many times since. For example, on October 12th, the former Israeli Prime Minister Naftali Bennett said simply: “We’re fighting Nazis.”

As we approach the first anniversary of October 7th, there’s a battle raging about what meaning to make of these reawakened memories.

These opposing ways of leveraging Holocaust memories are not equally relevant for today. In the months since October 7th, over 40,000 Palestinians have been killed by direct Israeli attacks. Furthermore, back in July, the well-respected medical journal, The Lancet, estimated that at least 186,000 Palestinians had died from other effects of warfare, like disease and infrastructure collapse. Meanwhile, at least 1,200 Israelis have been killed, and the Israeli hostages and their families have suffered terribly. All life is precious and must be mourned, but these numbers tell the true story about power.

Not all Jewish fears are historic. This past year of horrors, has increased tensions globally, and the 2023 FBI crime report showed a sharp rise in hate crimes towards all minority groups in America, including antisemitic and Islamophobic incidents. However, Jewish people are not currently subject to government-based persecution, as we were in Germany in the 1930s or as Palestinians are now. Genocide scholar Raz Segal argues that comparing October 7th to the Holocaust constitutes “a textbook use of the Holocaust not in order to stand with powerless people facing the prospect of genocidal violence, but to support and justify an extremely violent attack by a powerful state and, at the same time, distort this reality.” This is the world turned upside down.

What I hear underneath this faulty comparison, is unprocessed loss. C.S. Lewis famously wrote, shortly after the death of his beloved wife, poet Joy Davidman, “No one ever told me that grief feels so like fear.” Fresh loss often manifests as terror. My spiritual care work with newly bereaved clients begins with witnessing and validating their pain, so that I can help them gently restore their trust in other people and, eventually, the world.

It makes sense that my 1980s childhood Holocaust education was so filled with fear. After all, my father and my grandparents were survivors, and never had support to heal. But why is Holocaust grief still so fresh and unprocessed today, nearly 80 years after the liberation of the concentration camps?

Judaism is filled with powerful collective and individual grieving practices. And yet, there is rarely space in our synagogues or schools to explore how intergenerational Holocaust trauma continues to impact families like mine, or provide support for unwinding historical grief. More often than not, Holocaust education is intended to reify and reinforce existing fears, as opposed to promoting healing. Jewish author and cultural critic Naomi Klein, in her latest book Doppelganger, said that her own Holocaust education produced “surface-level emotions: horror at the atrocities, rage at the Nazis, [and] a desire for revenge,” as opposed to mourning or recovery.

Present-tense Palestinian suffering is often eclipsed by Jewish historical triggers on a geopolitical stage.

I sometimes wonder if it makes sense for me to be tending to inherited Jewish grief right now, in light of how much more Palestinians are losing. And yet, as Palestinian-American writer Sarah Aziza reminds us Palestinian journalists are risking their lives to tell the story of their suffering. We all have an obligation to witness these losses. Aziza continues: “Grief and anger are appropriate, but we must take care not to veer into solipsism, erasing the primary pain by supplanting it with our own.” Today, all too frequently, unresolved Jewish grief is doing exactly that. Present-tense Palestinian suffering is often eclipsed by Jewish historical triggers on a geopolitical stage. As a rabbi, I have a moral obligation to help my community grieve and heal so that we can bear witness to what is happening now.

How we tell our family stories and pass them on to the next generation is a place to begin. This year, I traveled to Brussels to try to learn more about my grandfather Max. At the National Archives of Belgium, in a yellowing file that hadn’t been opened in 80 years, I saw a photo of Max for the first time. I discovered that he had my father’s wry gaze. And I learned that he had died in Auschwitz only three months after his arrest, when he was 24 years old.

I also found out that Max had been a political prisoner for his activism, and that there were nearly a dozen other political prisoners from his Brussels neighborhood. After his arrest, it was these neighbors who helped arrange false Aryan papers for my grandmother so that she could go on to work for the underground. And those were the same neighbors who hid, bathed, fed, and protected my infant father.

Growing up, Max’s story had reinforced my Jewish fear and suspicion. But in reading this file, I suddenly realized that dozens of people, of all religions and cultures, had risked their lives and their own families in order to save mine. When I tell Max’s story to my child this new year, I will let her know that we owe our lives to solidarity. Now, it’s our turn to act.

I Come from Holocaust Survivors. They’re Why I’m Demanding a Ceasefire.