Photograph by Nicolò Rinaldi / Connected Archives

WORDS BY YESSENIA FUNES

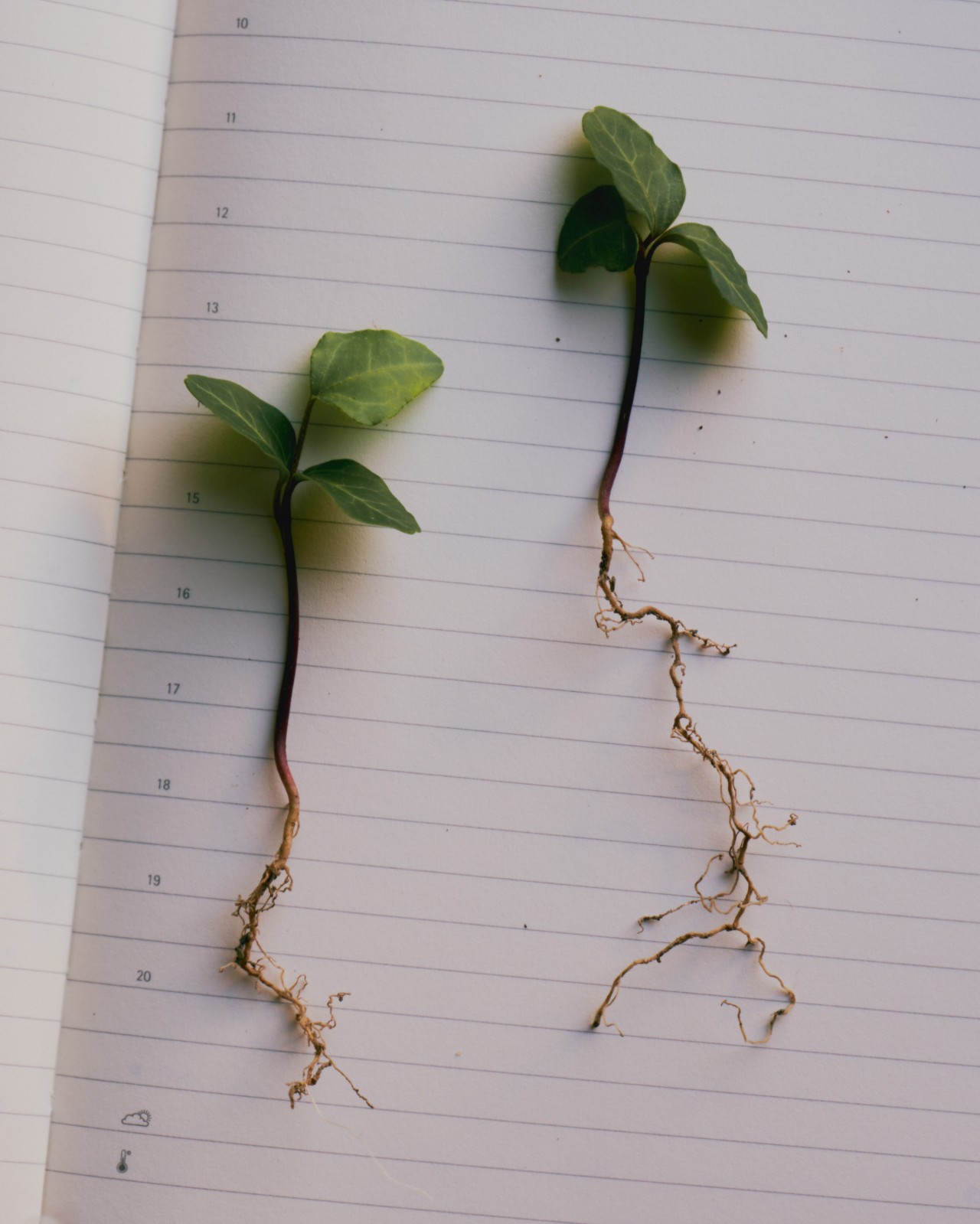

Brad Parry had a lot planned this year for the Northwestern Band of the Shoshone Nation, where he serves as the tribal council’s vice chairman. Since 2018, the Utah-based tribe has been working to terraform the Bear River watershed near the Idaho border to its pre-colonial state—before settlers arrived with their invasive Russian olive trees and disruptive irrigation canals. Since 2023, the Northwestern Shoshone have won over $6 million in competitive public grants to make this vision a reality; they’ve already added 10 acres of wetlands, removed 30 acres of invasive species, and planted 60,000 Native plants and trees across 65 acres. Perry had hired contractors and biologists and secured permits to continue that work in 2025.

Now, everything is on pause.

Donald Trump, on his first day as president, issued an executive order directing all federal agencies to “terminate … ‘equity-related’ grants or contracts.” A few weeks later, Parry’s funding disappeared. The United States treats tribes as sovereign political entities, not racial identities—but that hasn’t stopped the government from targeting Indigenous communities by either shutting down diversity, equity, and inclusion programs or more universal cuts to federal programs and workforces.

“I checked the account last week,” Parry said on February 13. “The line item was gone. The money was pulled back, and we already spent half of it.”

The Shoshone aren’t alone: Across the U.S., Indigenous communities, organizations, and researchers are stuck in financial limbo as they await clarity on the future of their contractually obligated funds. Even those with access to their dollars are wary of spending them in case the federal government cancels them later on and refuses to issue reimbursements.

“It’s a big financial crunch for us,” Parry said.

The previous administration formally recognized the value of Indigenous knowledge and wisdom, especially in combating the climate crisis. In 2022, President Joe Biden’s administration published guidance on how federal agencies can include Indigenous knowledge in their policy and decision-making. The document read: “Indigenous Knowledge can provide accurate information, valuable insights, and effective practices that complement practices and knowledge derived from other approaches. For example, at times Indigenous Knowledge holders have observed early and accurate detection of environmental changes, such as interconnected patterns of species, signs of drought, or impacted water quality.”

In Utah, for example, the Shoshone’s ecological restoration project is estimated to bring back 13,000 acre-feet of water to the Great Salt Lake, which is fed primarily by the Bear River. Utah will need all the water it can get as rising temperatures from fossil fuel pollution trigger more severe droughts and wildfires in the state. The reintroduction of Native plants would also improve the region’s water quality by preventing less sediment and runoff pollution. These are benefits to all local stakeholders, not just the tribe. However, the Northwestern Shoshone people are uniquely positioned to heal the land.

“We have fought against drought and climate,” Parry said. “That’s all cultural and spiritual beliefs for us: Don’t mess with Mother Nature, and it won’t attack you because Mother Nature is 100% undefeated. If you fight her, you end up with drought and bad air and water.”

“The cuts really weaken the ability of us as a tribal community to lead these innovative land-relationship practices that benefit the ecosystem and all people alike.”

In Alaska, those knowledge systems have developed in tandem with the ice. Historically, Alaska Natives have been seasonally migratory, but colonialism forced them into fixed villages. Today, many don’t have roads and, instead, rely on boats or planes. Some villages still lack basic infrastructure, like water, electricity, and sewage. Electricity is critical during the cold winter months to keep houses warm and freezers cold. Many Alaska Natives store their fish and meat in freezers to eat year-round. A power outage can cause food to go bad or damage buildings if water pipes freeze and burst.

One Alaska-based tribal organization has $130 million on hold, threatening its ability to deploy essential services and clean energy projects across the state. The funding pause risks the potential for increased construction costs and delayed timelines, ultimately making these projects too expensive to pursue. One grant would have helped communities replace dirty diesel generators with tribally owned solar energy they can use during the bright summer months.

“We’re forcing an unlivable situation on these communities if we take away electricity and water and schools and even airports from them,” said one scientist who is withholding the identities of their organization and themself. “There’s no way to survive in these places without reliable energy.”

One Alaskan tribe that wishes to remain unnamed has at least $2.5 million in grants available to build a local environmental monitoring network for salmon and other wildlife, but leadership has had to adjust how they tap into their funding in case it’s revoked. They can’t hire people only to fire them months later. A local workforce, however, would save the U.S. money in the long run, the tribe argues. Sending scientists to the Arctic is costly. Why not hire the Indigenous experts already living there?

“What we’re talking about here are efforts that directly address issues of the day, such as biodiversity loss, habitat fragmentation, and climate change among Indigenous nations,” said a tribal director, who agreed to speak anonymously. “The cuts really weaken the ability of us as a tribal community to lead these innovative land-relationship practices that benefit the ecosystem and all people alike.”

The federal funding freezes also threaten to undo all the years researchers have spent building trust with Indigenous communities.

“Breaking trust happens very quickly, and it’s really hard to get back,” said Dr. Paulette Blanchard, a co-principal investigator of the Rising Voices, Changing Coasts climate research project and citizen of the Absentee Shawnee Tribe. While her funding stands, at least three organizational partners—including government agencies—have walked away to comply with Trump’s executive order on diversity, equity, and inclusion.

Through trust, tribal nations have felt safe to share their sacred ancestral knowledge with outsiders in the first place.

“For Indigenous scholars, when we do a grant or project, we work with knowledge keepers and spiritual leaders so that the benefits of a project are shared among those people,” said James Rattling Leaf, the principal of research consultancy at Wolakota Lab LLC, whose climate work at the University of Colorado Boulder feels precarious. “Whenever a project gets defunded or canceled, there’s a tremendous impact.”

“Indigenous science is embodied by a love so deep and rich and everlasting that it touches everything on this planet. And that’s what Western science lacks.”

Indigenous youth are especially vulnerable. In 2023, only 16.8% of Indigenous peoples in the U.S. 25 or older had a bachelor’s degree or higher. In New England, one Native researcher was scheduled in January to kick off a program to support Native students through paid internships, tutors, and mentors. Now, his funding is on indefinite hold. He still hasn’t figured out what the students will do without the program.

“This is a crisis upon crisis right now,” said Sammy Matsaw Jr., a member of the Shoshone-Bannock Tribes and former leader of the tribal business council.

He earned his doctoral degree in water resources at the University of Idaho. With his partnership, the university won a grant to support 12 graduate students who are citizens or descendants of tribal nations and pursuing a master’s or doctorate in interdisciplinary STEM fields. The team hasn’t lost the grant, but the uncertainty has left them distressed. Everyone loses without these researchers, said Vanessa Anthony-Stevens, an associate professor at the university who also works on the project and is white. She recognizes that the perspectives of her Indigenous students are irreplaceable, their contributions immeasurable.

For instance, doctoral candidate Shanny Spang Gion, who is Northern Cheyenne and Crow, has been working closely with her community in an ongoing research project modeling how the Tongue River’s water flow will change by 2100. The river outlines the Northern Cheyenne Reservation’s eastern border.

“That connection to community and the ways that we bring ourselves to the work matter,” Spang Gion said. She’s concerned that the Trump freeze will affect her ability to keep studying the river dynamics.

“These funding cuts are another attempt at oppression,” she said.

After all, Indigenous science is Indigenous culture. Tribal nations have fought hard to keep their oral histories and traditions alive despite colonization, genocide, land thefts, boarding schools, and other systemic violence from the U.S. government.

The Northwestern Shoshone in Utah know these legacies well. In 1863, about 500 of their ancestors—men, women, and children—faced violent execution by the U.S. military. The Bear River Massacre remains North America’s largest Native American massacre in history. Now, the tribe wants to restore the very earth where this blood spilled. The land needs healing—not just ecologically but spiritually, too.

The tribe wants Wuda Ogwa, Shoshone for Bear River, to flow free again.

“Being able to free the Bear River is a symbol of how we want to exist and travel and flow in our natural way,” Parry said. “We’re a sovereign nation. We’re not DEI. It’s about our Indigenous peoples trying to get back to their roots.”

The U.S. was founded on the rights to “life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness,” but much of its people seem to have forgotten what sits at the heart of freedom: love. Indeed, the word “free” has origins with the words “to love.” Indigenous science is embodied by a love so deep and rich and everlasting that it touches everything on this planet. And that’s what Western science lacks. Love is what the climate crisis demands.

“By weaving Indigenous knowledge and scientific culture, we could fight climate change together,” Parry said. “It’s a symbol of how we want to go back to our roots and show we can take care of each other and ourselves if we work together.”

Gutting Federal Funding Undercuts Massive Strides in Indigenous Science