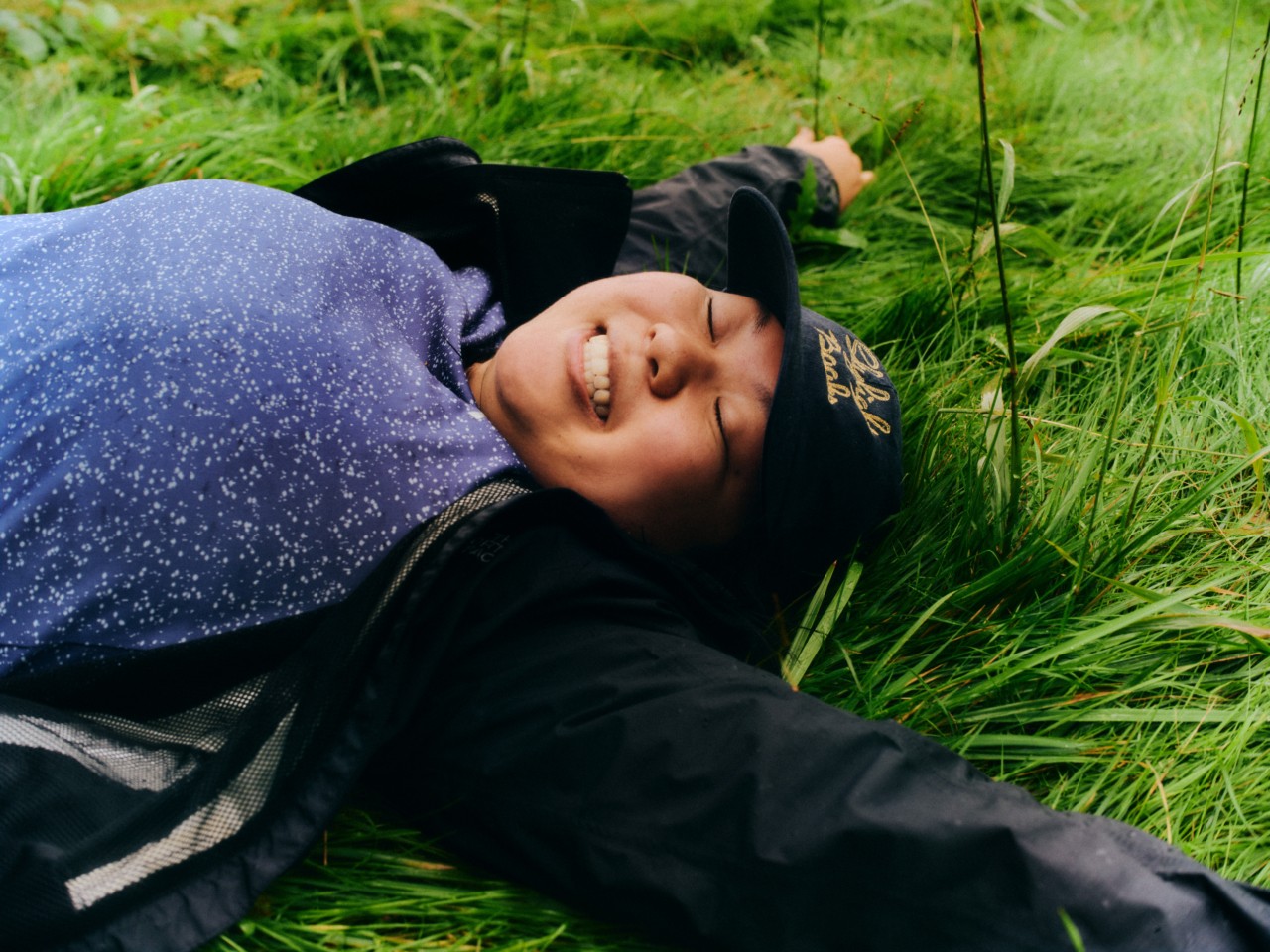

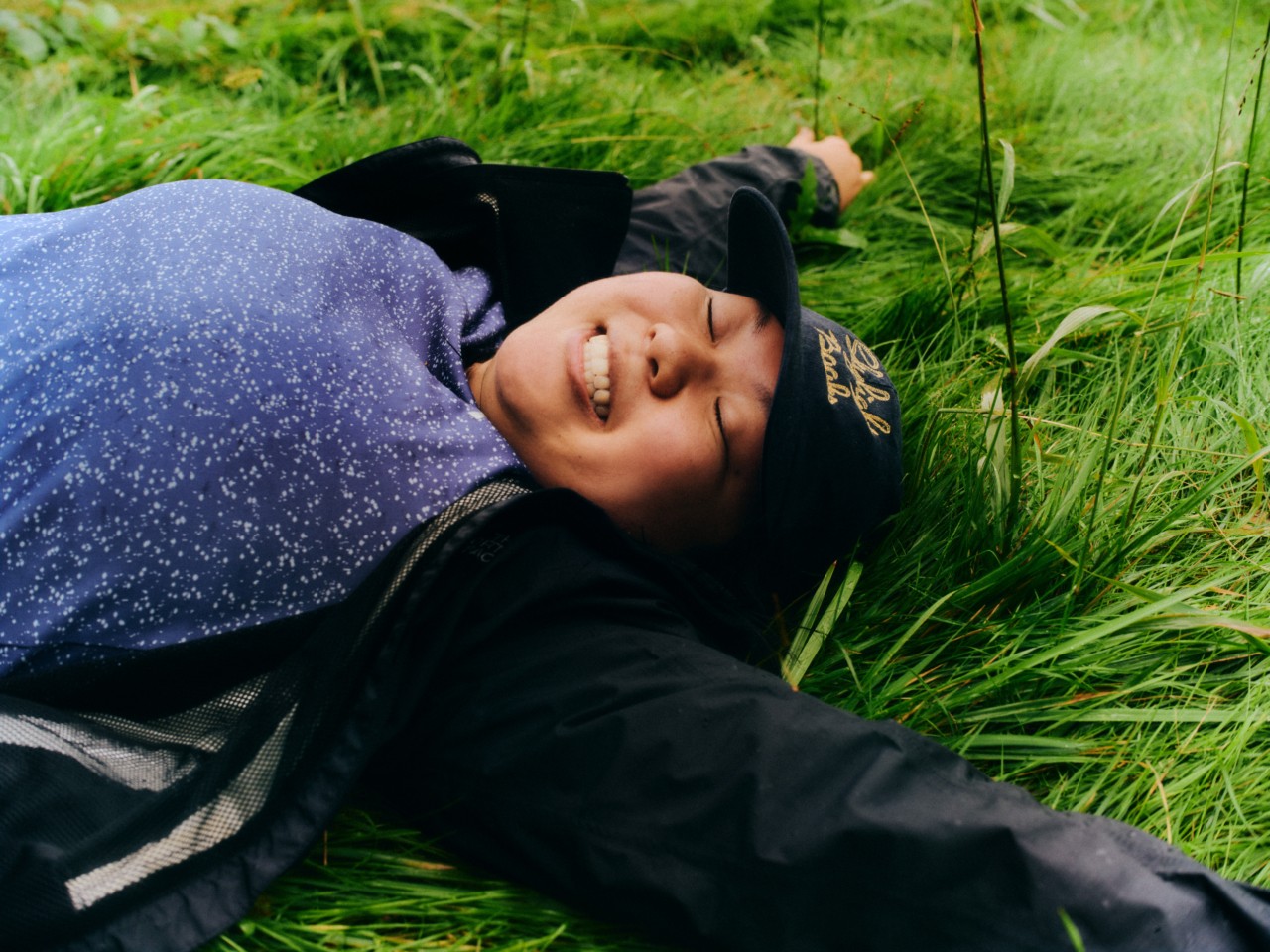

Photograph by Heather Sten

Words by Lauren Cochrane

Photographs by Heather Sten and Poppy Thorpe

When Chelsea Rizzo and Allison Levy first thought about setting up Hikerkind, their brand that brings a much-needed sense of style to women’s outdoors clothing, they were clear it wasn’t just about the product. Just as the first collection of clothes launched, so did a hike club. “We’d been kicking around the idea [for some time],” Rizzo told Atmos. “The thing that pushed us over [to do it] was we wanted other people to go hiking with.”

Started in 2021 with a few friends, the most recent hike in New York numbered 65 people (mostly women), and Hikerkind now has clubs in Southern California and Seattle. “It’s really exciting to see other people out there like us,” said Rizzo. “I think that’s what we’re all searching for—people to connect with and to not feel alone.”

This impulse can be seen in the recent boom of hike clubs that cater to women, LGBTQIA+ and BIPOC communities, often with an intersectional perspective. See Hike Clerb, founded by Evelynn Escobar in LA in 2018 as an intersectional women’s hiking club. Or Gorp Girls, an organization that hosts hikes for women in the UK and LA. There’s also Black Girls Hike, founded by Rhiane Fatinikun in 2019, as a safe space for Black women to explore nature across the UK. And Feminist Bird Club, a twitchers’ club for the LGBTQIA+ community, BIPOC and women. Founded in 2016 by Molly Adams, it now has chapters across the US and Europe.

The popularity of these clubs is a direct response to the way that outdoor spaces have—until recently—been considered the territory of white heteronormative men. A 2017 study by Natural England found only 26.2% of Black people and 25.7% Asian people spent time in rural settings, compared to 44.2% of white people. Women, meanwhile, have long reported incidents of sexual harassment and assault in outdoor settings. It’s why a hike club—a safe space with like-minded people—provides both strength in numbers, as well as joy in communities exploring off the beaten track together.

The founders of these hike clubs emphasize this point. “I started Black Girls Hike so women could explore the outdoors, it’s a safe space for all the community,” says Fatinikun. “We’ve introduced quite a lot of people [who] didn’t necessarily think it was for them, and now they’re really active.” Both Hikerkind and Black Girls Hike prioritize hikes with transport links so they are accessible for those who live in cities. Forget remote areas and all-terrain vehicles—this simple shift shows there are destinations on the doorstep.

Fatinikun, who has focused her career on community organizations, was partly inspired to set up the Black Girls Hike because “I personally wanted to get out and just do more with my wellbeing overall,” she said. This is something that is mirrored in others’ experiences. Adams says Feminist Bird Club began “as a way to feel safe in nature with other like-minded people,” but also potentially to fundraise for causes she felt passionately about—such as reproductive health and fighting against abuse of trans and intersex people in prisons.

Seven years later, and the organization’s dual track remains, with a clothing patch embroidered with a different bird produced each year as a way to raise money. “Feminist Bird Club has been able to donate over $125,000 to causes we admire thanks to revenue earned from selling patches and merchandise, bird-a-thons, and other fundraising efforts across our chapters,” said Adams.

Despite the boom in hiking clubs having made their members more visible, there is an argument that they have been there all along. They have just been underserved by wider outdoorsy culture. “I think the revolution we are currently experiencing is that more folks feel able to identify as a birder or as outdoorsy,” said Meghadeepa Maity, cochair of Feminist Bird Club. “Visibility and representation are critical and when we center gender minorities, BIPOC, and disabled birders, more of us feel able to loudly and visibly occupy outdoor recreation spaces and communities as our complete and authentic selves.”

The growth of the organization—it now has over 30 chapters—is testament to how communities have chimed with the idea. “It’s sometimes hard to wrap my head around how much the group has grown and evolved,” said Adams, “but as someone who is queer and disabled, Feminist Bird Club events and community mean so much to me. Over the years I’ve seen firsthand how much support they provide to others involved across the chapter network as well.”

A hike club provides both strength in numbers, as well as joy in communities exploring off the beaten track together.

In tandem with the growth of these hike clubs comes brands that make clothes beyond what Rizzo described as “the shrink and in pink in effect”—referring to how brands had previously made outdoors clothing for women smaller than the men’s clothing, and in garish colors. Along with Hikerkind, there’s Early Majority. It was set up by Joy Howard, formerly the global vice president of Patagonia, and serves as a rethink of who has access to nature. “Everything about [outdoors brands] is really designed around men’s adventures,” said Howard. “And so it’s not surprising that we, as women, felt there were no products that speak to us.”

Instead, Early Majority creates clothes that look good and work for outdoorsy settings. Genderless and minimal, they are likely to appeal to the demographic that form part of hiking clubs. A membership model adds to the appeal. A windbreaker at full price is £195 ($238), while a member pays £109 ($133).

Rizzo and Levy both worked in fashion previously (they met on a shoot for Gucci), and bonded over hiking. They were frustrated with what they were wearing and saw this as a fundamental part of the movement to make outdoors spaces more inclusive. “We love being outside and it’s really where we both feel like our most authentic selves,” said Rizzo. “We felt like the clothing that we had no choice but to buy and wear directly clashed with that feeling. And it made us feel like we were in costumes and it made us feel very disjointed.”

“I think that’s what we’re all searching for—people to connect with and to not feel alone.”

City hiking may be an increasingly important element of the outdoorsy world. As evidenced by the transport-first approach taken by groups including Hikerkind and Black Girls Hike, this recognition aligns with the clothing designed, too. “We believe anything where you’re traveling outdoors with a destination in mind is considered a hike,” said Rizzo. “Where’s the apparel for the person who lives her life in between those two extremes?” Howard agrees. “We wanted to design something that would speak to the needs of women, that would speak to the needs of city dwellers,” she said.

One of Hikerkind’s most striking designs is the hiking dress. Inspired by a silhouette the founders wear “day to day,” it brings the ultimate feminine clothing items into a new space. “You can see [consumers’] brains start to be like, Can I hike in this? Why can’t I hike in this?” said Rizzo. “There’s a lot of features about the dress that are super, super intentional. It’s made in a material that’s extremely technical. It’s backpack strap friendly because we put a sleeve on it. It performs just as good as it looks.”

The future of hike clubs resembles the impact of the clothing made by these women-owned brands: the power comes from visibility where it wasn’t before. “These days, folks in traditional outdoor spaces are more cognisant of the unique challenges some of us face,” said Maity, who emphasizes the importance of solidarity. “It’s easier to advocate for our needs when we all share similar barriers to the outdoors. That sense of safety and belonging feels more organic in our spaces even when we’re not actively talking about our identity and lived experience.” Anyone looking to head outside? They should join the club.

Claiming Space: The Hike Clubs Putting Women First