Photograph by Daily Herald Archive / Getty Images

Words by Georgina Johnson

Photographs by edvinas bruzas

I have just finished writing my book, The Slow Grind: Practicing Hope and Imagination. It’s the follow-up to my first, which I self-published in 2020. Before the term intersectional environmentalism became popularized, my research explored the connection between social justice, climate justice, and mental health. This was to become the anthology, The Slow Grind: Finding Our Way Back to Creative Balance, driven by my belief that a collective voice is a vehicle for communal understanding.

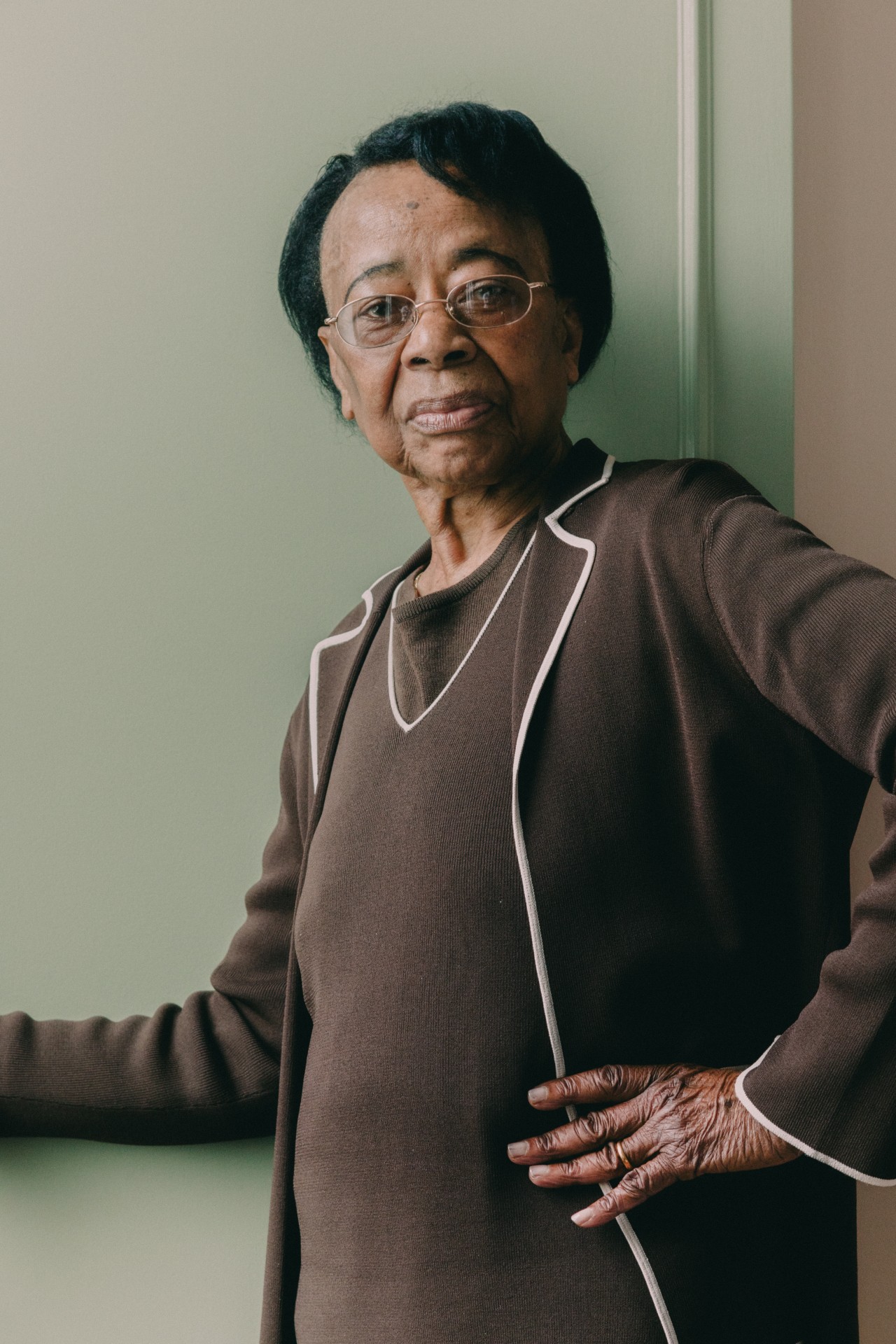

What I didn’t expect was how much of an intergenerational exchange and new point of connection working on my book would create between myself and my 84-year-old nan, Lerma.

Since its publication, we have had more conversations than ever before about the world she knew growing up in Jamaica. We’ve discussed mental health, climate degradation, and the vital role of memory and imagination in relocating ourselves back to the land. We’ve discussed the relationship between the peoples that inhabited and continue to inhabit the Caribbeans, and the land they tilled; trees her and her siblings swung from as children and plantations that you can still see and feel the remnants of. And we’ve discussed the place of all of this in our soul and body.

I love the conviction in her voice when she sees something on the news and says to me on the phone, “You see Georgina, this is why your work is so important, because people need to know about what’s happening around us.” It proves to me that it can never be too late to unlearn and relearn.

In my new book, culture baddie Zeba Blay muses on the power of writing: “My main preoccupation when I sit down to write is to try to be in conversation with my community, with myself, and with God and that is the defining compass for me when I write now… I’ve been asked in the past, can writing change the world? I think it can in subtle ways.” I share this belief, too. It is the written word that collates memory and keeps time. It sparks conversation and opens minds to the complexities of life and history. It’s a tool of empathy and imagination, enabling us to unpack what is within us and to move beyond it. It can help us examine intersectional questions and engage in the project of expanding ourselves. It can prompt us to contemplate the journeys of our ancestors and help us map our own.

My grandparents are part of a generation of original dreamers. Those that made the voyage on The HMT Empire Windrush in 1948 from Kingston, Jamaica to Tilbury, England and the ships that followed. Those who imagined a new life in a place that they believed would give them more stature, opportunities, and prospects for their future families. They dreamed for all of the second and third generation Black Britons of Caribbean descent. Over the last 75 years, through sheer tenacity, hope and imagination, this generation has shattered the very notion of what it is to be British—and with it, gifted the color and vibrancy of our culture to this Island, which would have otherwise been pretty dry.

Over the last 75 years, through sheer tenacity, hope and imagination, this generation has shattered the very notion of what it is to be British.

It is impossible to deny how invaluable and impactful the contribution of the Windrush Generation has been to Britain. But we have largely underestimated the impact of those times on the Black psyche. In so doing, we have also failed to unpack the omnipresence and multidimensionality of grief.

The “savior” that whiteness painted itself for centuries is one of the reasons why mass migration from the Caribbean to Britain was so successful. Britain’s indoctrination of itself as the “mother country” meant that its call to repair post-war Britain was met with bodies ready to do just that. The building of another place, the home of the oppressor, felt natural. Maybe because the centuries of dispossession held within us meant that we unconsciously came to know that gaining greater proximity to whiteness was safe. If you answer the call of the oppressor, maybe you too can benefit from her privilege. Maybe you, too, can gain some of her power. But when Caribbeans came to Britain in droves, they were unwanted and largely rejected in nearly every sphere of society. The formidable matriarchs in my family built and fortified a young National Health Service, my Grandfather and his cousins manned the transport systems, all the while being abused, their care of patients rejected, and their mobility impacted through housing insecurity and earning on average just £5 a week.

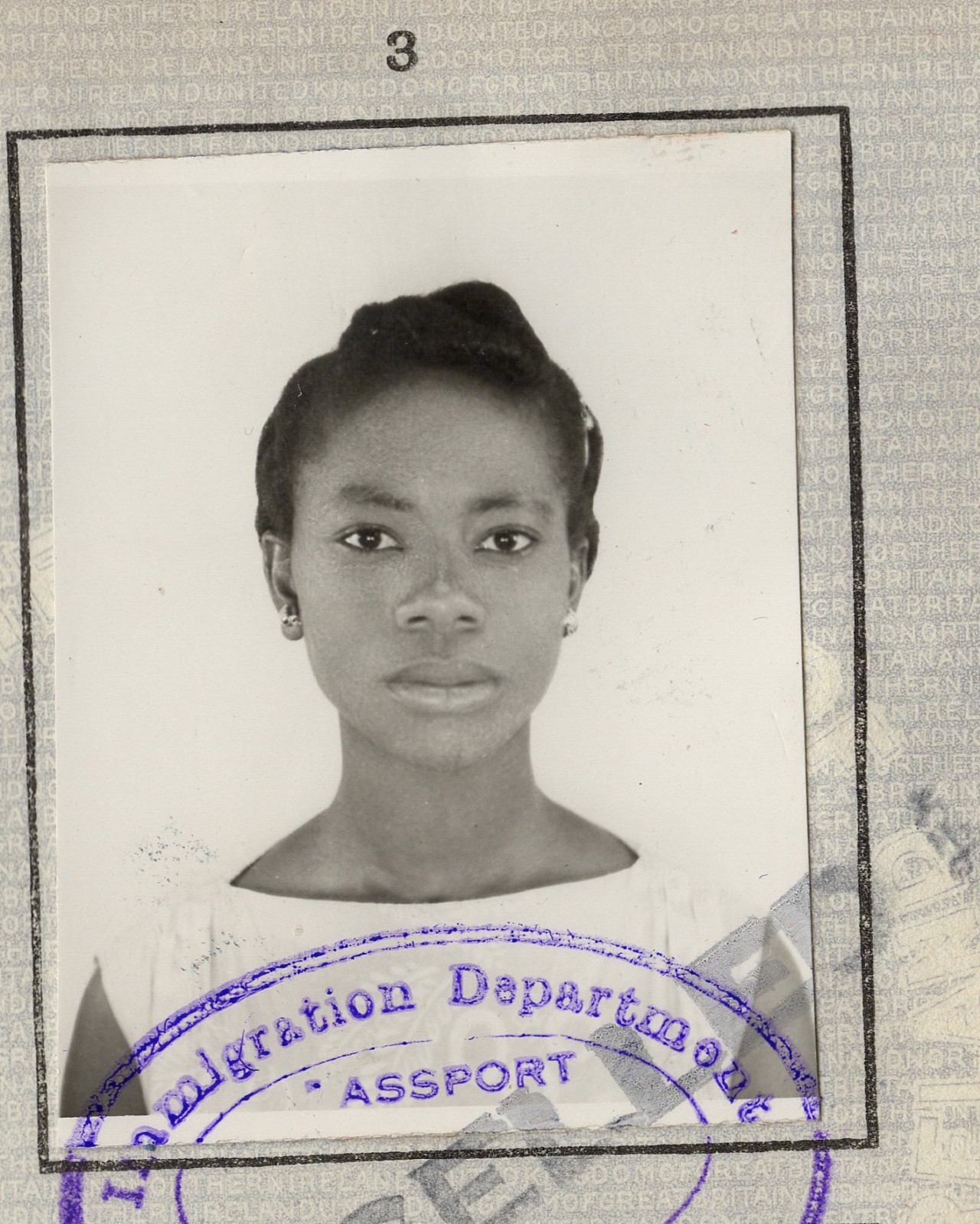

I found my Grandma Maudline’s passage papers to the U.K. in 2020 as well as old personal papers she’d kept when my family were clearing her home ready for sale. She has progressed dementia, which means she doesn’t remember any of us and cannot look after herself. Dementia is a thief. And I get frustrated at myself for not asking more questions when I was younger—because now that my nan is 99, the gravity of the fact that she lived through nearly the entire 20th century is not lost on me.

It is hard to reckon with the loss of history that dementia causes. Especially within a certain generation and body of people. Because much of Caribbean history is transmitted through orality due to the chronic erasure of knowledge systems by the British Empire. And so, once again, I get annoyed at myself for not asking enough questions. About the Jamaica she knew as someone who was raised by her own grandparents, former slaves. About what the slow shift out of the slavery system must have been like. About what the Jamaica of the 1930s smelled and looked like. About what was in the air when Jamaicans gained voting rights in 1944 and independence from Britain in 1962. I want to know if she knew that she wouldn’t return to live in Jamaica when she left for the U.K. in 1955. I want to know it all… from her.

From the dates on the notes, bank statements, letters, and nursing diary she kept, I can create a picture in my mind of what her life must have been like coming to Britain. It looks as though she began her nursing training pretty much as soon as she got off the boat. The earliest date in her notes is September 22, 1955, in which she writes that she passed both her theory and practical tests on the first attempt. In her nursing training journal she writes about the qualifications of a good nurse: “She must be intellectual, healthy, have good manners, an even temper and self-confidence… training will strengthen these qualities. Loyalty is also very essential.” Her journal is so detailed, with ink-written notes that document an education on every part of the body and care of patients. From connective tissue to drawings of the heart to documentation of a patients’ “cranial fossa,” seeing the ways in which she likens brain nerve systems to “tree-like formations” and areas “the size of an orange” is mesmerizing. This formidable woman threw herself into the healthcare system wholeheartedly.

In the BBC Sounds series, Windrush: A Family Divided, husband and wife Jennifer and Robert Beckford take a brief look back on the 75 years since The Empire Windrush docked at Tilbury. Their series seeks to examine the impact of that mass migration on the diasporic community of today by asking: Was the Windrush Generation better off after coming here or should they have stayed in the Caribbean? As part of their journey, they interview returnees as well as second and third generation migrants that have stayed and sought to continue building a life in Britain in order to explore the complexities of this question. The Beckfords disagree in their conclusion: while her husband believes that children of the Windrush Generation gained much, Jennifer asks: Why not go back and build up your own country? Windrush: A Family Divided reveals how many in the diaspora are reluctant to go bakka yard for fear of safety and lack of resources. In other words: the Black imagination has been captured and our desires morphed—because it is the same place, the British Isles, in which many sought safety and opportunity that created the unstable socioeconomic and sociopolitical environments of their homelands as a result of its history of plunder and the stripping of land rights and political control.

I wonder what the Jamaica of today would look like if more of those who left and upskilled were to return to enrich, fortify, and safeguard their own land. Home to critical marine ecosystems, vulnerable species, and 10% of the world’s coral reefs, the Caribbean is one of the places most affected by the climate crisis and climate colonialism. It is also often left out of climate conversations. Locals are being pushed out by rampant land developments, native ecosystems are being degraded, and many islands haven’t recovered politically or economically from the times of European slavery.

And so, many still rely on coin from the West. This is what advocacy group Jabbem—Jamaica Beach Birthright Environmental Movement—is fighting against. The organization is campaigning to repeal colonial-era laws like the Beach Control Act of 1956, which states that the British crown continues to maintain all rights to the foreshore. It also states that the public has no innate rights to access it. Their vision is clear: they want the government to make beaches public as currently only 1% of them are accessible to Jamaicans. This, in turn, prohibits locals from fishing, going to beaches, and accessing the waters that surround their island. “Jamaica came into emancipation landless and homeless and that situation has not changed,” Jabbem founder Devon Taylor told Al Jazeera.

One fisherman, Norris Arscott, tells of the beaches between the parishes of St. Ann and St. Mary that are blocked off to him—the same beaches that he and his ancestors have fished for over 70 years. St. Ann is also the parish my nan, Maud, is from. In a letter to my dad in 1981, she writes from back home— Strawberry, St. Ann Parish, Jamaica—on a visit. Reading her letter in her tone of voice is special: “Your aunt, she old and shaky but still up and about, your great-grandfather is blind and cannot do anything for himself. My dear children, Jamaica is in a poor state, but I believe God will help.” She ends the letter with “please don’t go hungry and water my plants.”

Strawberry, St. Ann is known for its beautiful coastline and its “red soil and bauxite—an essential mineral to Jamaica that comes from the underlying dry limestone rocks of the parish. Her ancestors built their homes on that soil, but it is today an area in which her own people are not welcome.

Generation Windrush taught us that dreaming is revolutionary; world-building. That dreaming with intention and care can change the course of history.

My nan Lerma speaks often about how wonderful it was to step out of the house and pick a mango from the tree right outside. About their assurance in the nutritional value of their food because they knew the soil it grew from. How warm waters to swim in could be found easily, and banks to dry in the sun with a fresh orange in hand also. They didn’t know happiness as plenty, but as enough. This ethic is out of line with the race for capital. Instead the Caribbean islands are drained of their resources, coastlines increasingly encroached upon, and their people are being displaced.

Today—our islands, our cultures, and our histories are at risk. In order to preserve and restore the future we must seek the truth of the past. Generation Windrush taught us that dreaming is revolutionary; world-building. That dreaming with intention and care can change the course of history. But how can we rebuild that which has been broken and lost? Perhaps it starts with seeking out and documenting the knowledge, the experiences, of our ancestors. And sharing our learnings with them in return. We all have a place in the fight to preserve our futures—we all have a right to dream loudly, and to hold hope.

Pre-order Georgina Johnson’s forthcoming book, The Slow Grind: Practicing Hope and Imagination, here.

Black Dreams: The Legacy of Generation Windrush