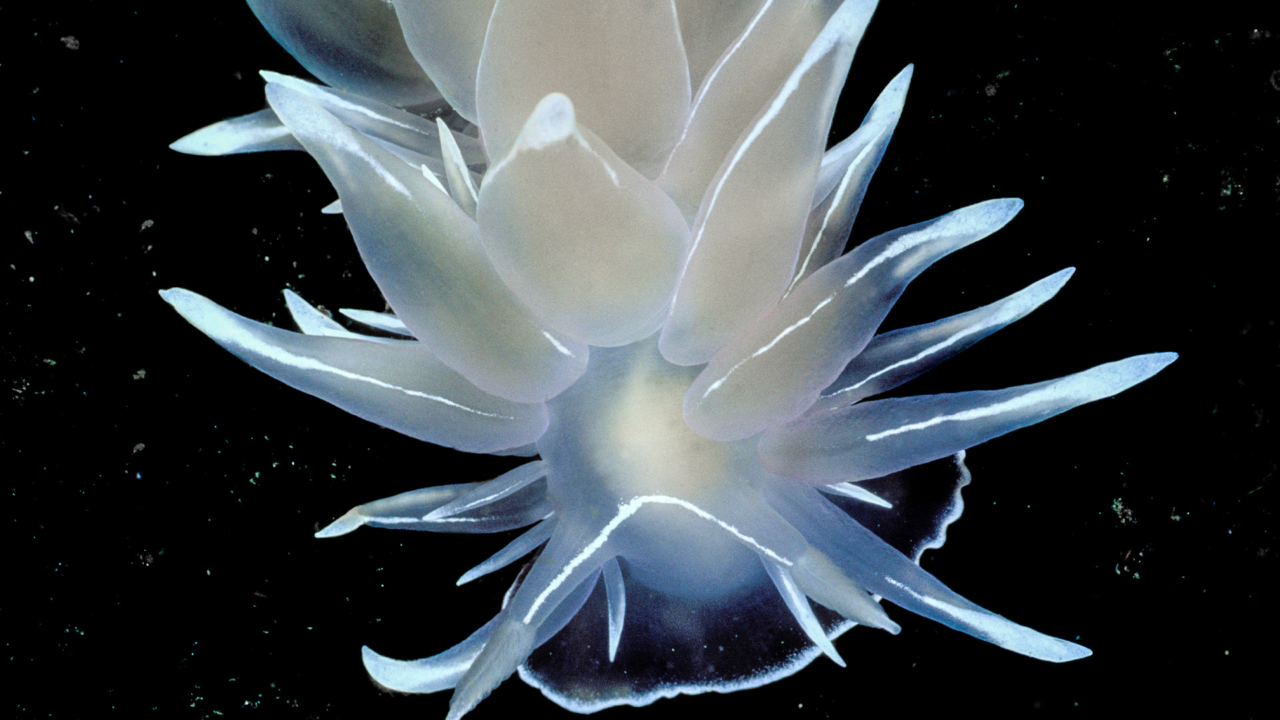

Photograph by David Hall / NaturePL

Words by willow defebaugh

“We know what we are, but not what we may be.”

—William Shakespeare

For as long as I can remember, I have been spellbound by stories of shapeshifting: myths and tales of humans taking other forms, contoured into new shapes and ways of being. When I was young, I would cloak myself in costumes of various animals for weeks at a time, refusing to change until I was ready to shed my skin. Growing up, I remember learning that some languages don’t have a word for identity because the idea of an unchanging self was impossible to conceptualize. I prefer to see identity that way: mutable, contextual, forever in flux.

Nature is rife with shapeshifters. My favorites are those that dwell in the depths: sea slugs. These marine gastropods come in a range of shapes, sizes, and vibrant hues that shift not only from species to species, but within an individual’s lifetime. Their various forms have earned them monikers of angels, dragons, hares, clowns, and even sheep. And sea slugs challenge our binary notions of sex; they are hermaphrodites, meaning they can mate with any other adult member of their same species and can even penetrate one another simultaneously.

Among the most beloved sea slugs are nudibranchs, whose name means “naked gills” after the horns and ethereal gills that grow from their backs. From vibrant violets to fluorescent oranges and electric blues, their kaleidoscopic colorations are entirely dependent on their diets, embodying the idea that you are what you eat. Adapting the shades of the algae, sponges, and anemone, they ingest helps these sea slugs stay safe and camouflage in their environments.

Some species of nudibranch have even developed the ability to absorb the potent poisons of prey and other animals such as jellyfish, manowar, and anemones. They take in the stinging cells of these creatures, called nematocysts, and store them in the tips of their tentacles so that they can then use them as a defense mechanism against their predators. In other words, they have found a way to turn the toxicity that would be levied against them into a means of survival.

Sacoglossans, another order of sea slugs, have evolved their own unique shapeshifting prowess known as kleptoplasty. They absorb the chloroplasts of the plants and algae they ingest, which then live on in their bodies for months and even longer than a year. These chloroplasts are what allow plants to get their nutrients from the sun—an ability that then gets transferred to the sacoglossan, making them the only known animal capable of photosynthesis. Taking on their resemblance too, these “walking leafs” blur the boundaries between the kingdoms of life.

This kleptoplasty allows certain sacoglossan sea slugs to perform another miraculous feat. They are able to discard their entire bodies and grow new ones from their heads, which can survive for weeks at a time due to their ability to photosynthesize. Because most animal regeneration is limited to appendages, scientists have called this the most extreme case of regeneration observed. And they seem to do this on purpose, rather than only when injured, though it’s unclear why. These bodies, while new, are exact replicas—even in shapeshifting, some constancy remains.

People shapeshift all the time. We take on what we take in, adopting new shades and silhouettes. We transmute poisons into protection, blurring binaries and boundaries. We shed old selves and grow new ones, both changing and remaining the same. Identity is a helpful container for awareness, but it can just as easily box us in. I aspire to spend this life exploring all my depths, a way of being that has less to do with the self and more to do with how we relate to the world. In times of crisis, I choose to see myself and others this way: always capable of change.

True to Form