Photograph by Charlie Summers / Nature PL

words by willow defebaugh

“Maybe ‘the point’ isn’t to live more, in the literal sense of a longer or more productive life, but rather, to be more alive in any given moment—a movement outward and across, rather than shooting forward on a narrow, lonely track.”

It’s been ten days since I arrived in London, and I’m reluctant to admit that I have barely left my hotel. I came for our final events for The Overview book, and stayed for a shoot. In the time between, I have been working with the team on finishing our next issue while sowing seeds for the future. Aside from that, I have only had energy to sleep—more than I have in years. As the days have slipped by, I have found myself asking a familiar question: where does the time go?

All I can say about time with certainty is that no one I know has it. And while our deification of hyperproductivity is nothing new, the unsustainability of it feels more pronounced in the years since our world came to a sudden stop in 2020. There’s a reason that time was transformational; when I used to teach meditation, I saw firsthand the power of taking people out of their daily routines, if only for an hour. When we step out of time, we gain perspective. But even that is temporary. We need to reimagine our relationship to temporality itself.

In Saving Time, author Jenny Odell traces the history of our attempts to tame nature and wrestle it into hours with two hands. She details how bound it is with capitalism through the notion that time is money. Where it was once a way to track the passage of existence, time has since become a commodity, something we give and take from others: “As opposed to the duration of life or even the processes of the human body, one hour is meant to be indistinguishable from another—decontextualized, depersonalized, and infinitely divisible.”

What has this way of seeing stolen from us? In climate work, I have found that the productivity mindset disguises itself as unequivocally gainful; I believe the more I work, the more I’m aiding a cause that is undeniably urgent. And yet, again and again, I have learned that my contributions to this movement are dependent on my ability to have perspective. As Tricia Hersey of the Nap Ministry once told me, that push and pull is part of it. You will rest and resist, surrender and succumb, and the cycle will repeat again. Liberation is nonlinear.

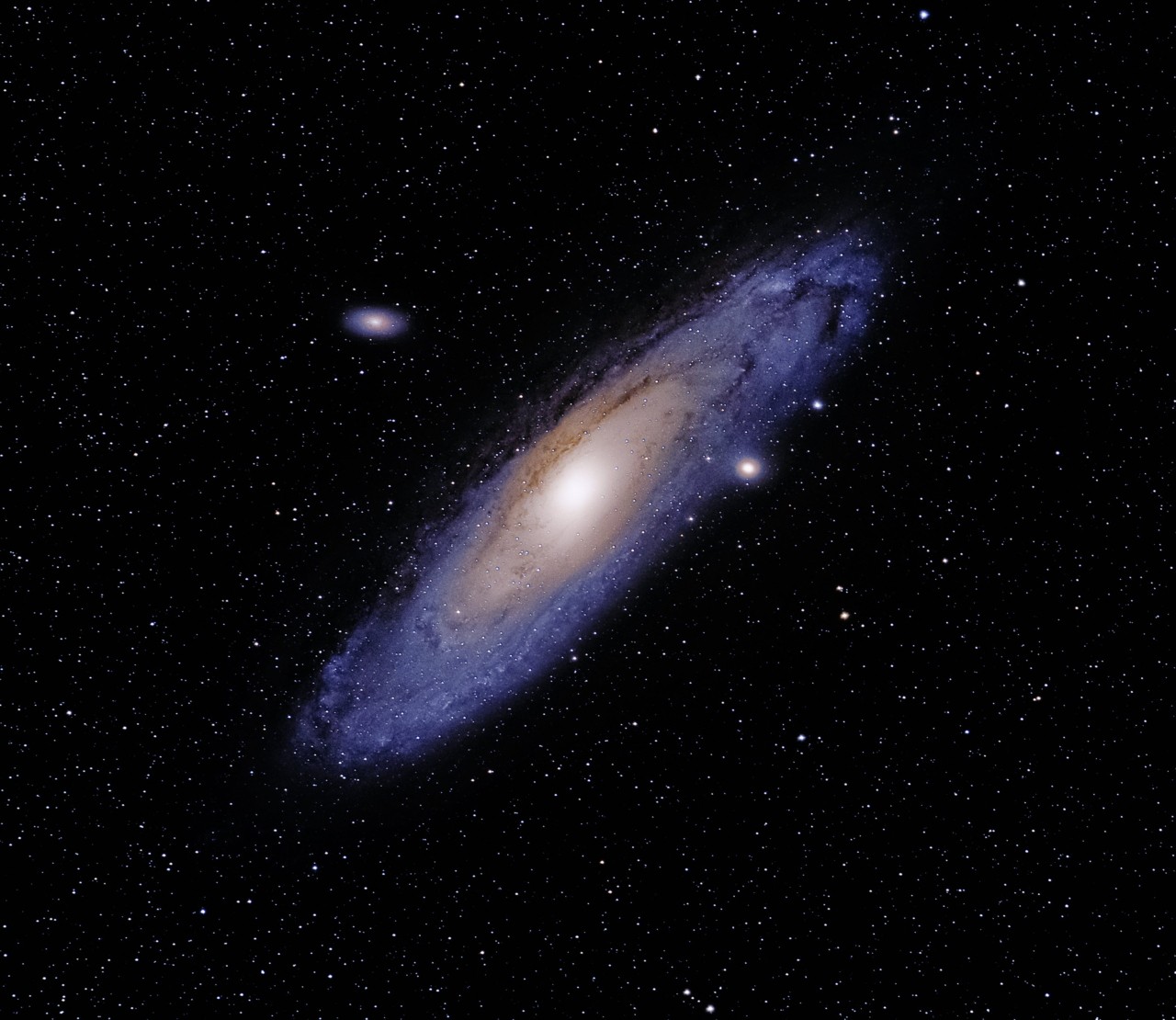

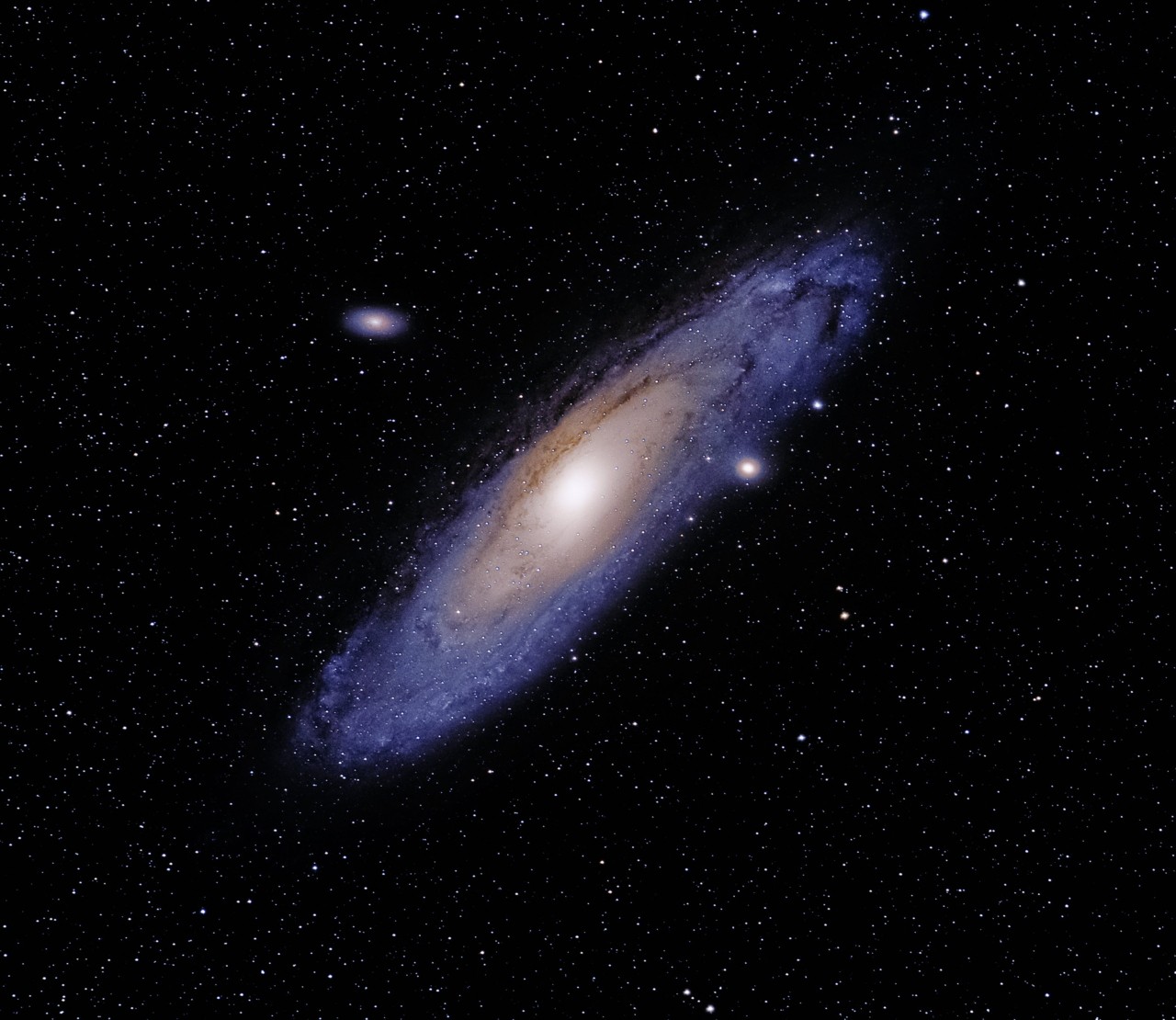

Of course, there are other ways of perceiving time. Deep time refers to a longer view of the Earth and the wider universe outside of human history, acknowledging all that has come before and all that will come after us. In geology, it is the story of stone and sediment; in astronomy, the uncoiling of the cosmos. When we are caught in the vortices of our daily dramas, deep time encourages us to see through the eyes of stars: to know that all of this is fleeting and precious and not ours. It restores time from resource to source, what connects us to everything else.

Odell points out that in Ancient Greek, two words exist for time: chronos and kairos. Chronos is the version we are more familiar with: the procession of linearity by which we measure our lives. Kairos, however, means crisis—or something close to a crucial time that must be seized. In the context of the climate crisis, perhaps it is chronos that we must release: rather than be weighed down by our perceptions of inevitable, impending collapse, can we view this as precisely the right moment to imagine something new? A world beyond extraction and exhaustion?

For all I have written on the subject, I’m still unlearning productivity culture and the discomfort I have around rest—allowing myself to take a moment and honor a massive chapter of my life that has just closed, rather than march relentlessly onto the next. Instead, I aspire to live my life by deep time, expansive and all-encompassing. A wider circle full of work, yes, but also everything else: idle hours, falling in love, smelling the flowers. Time not as something taken, but a gift.

On the Hour