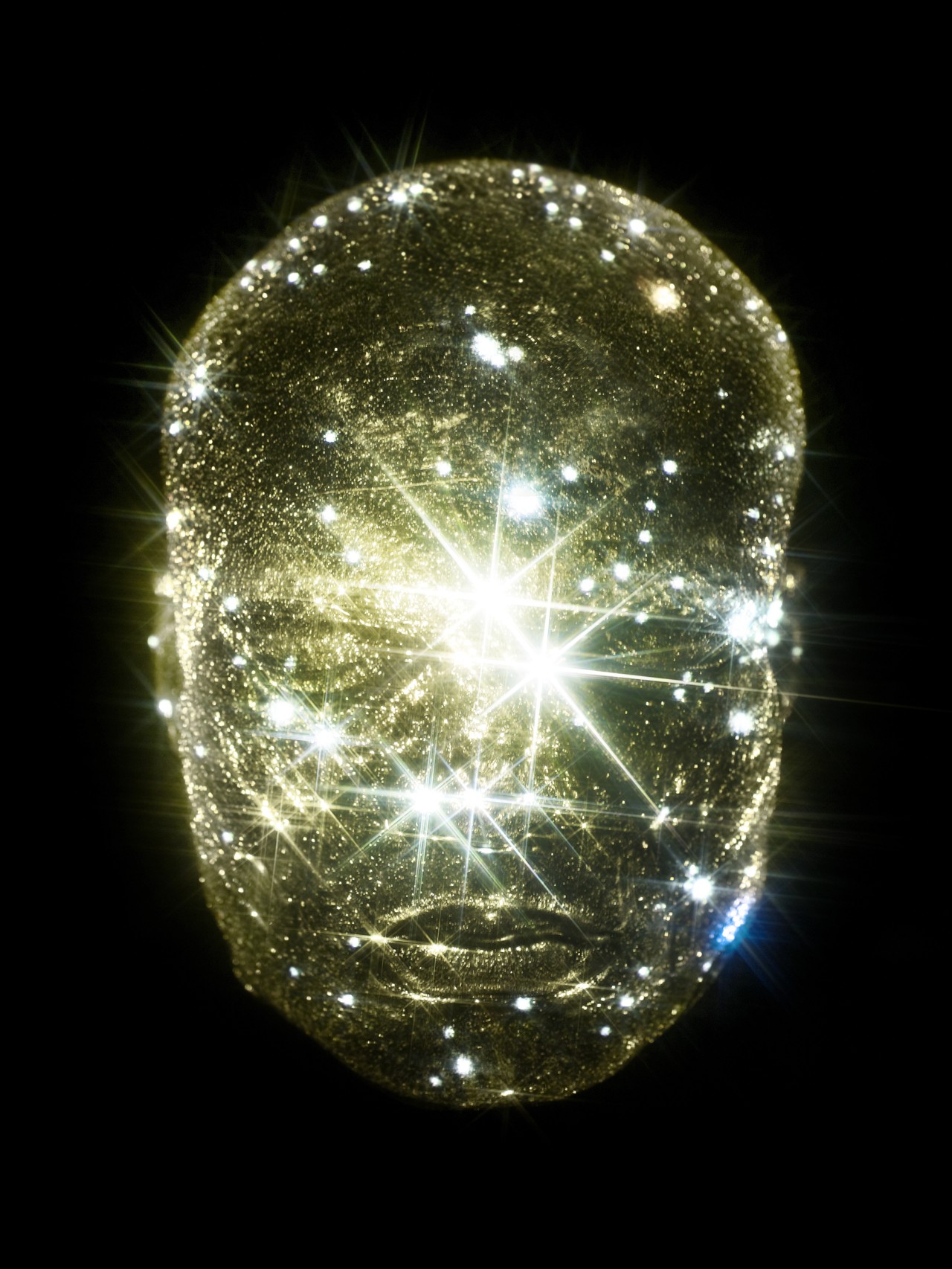

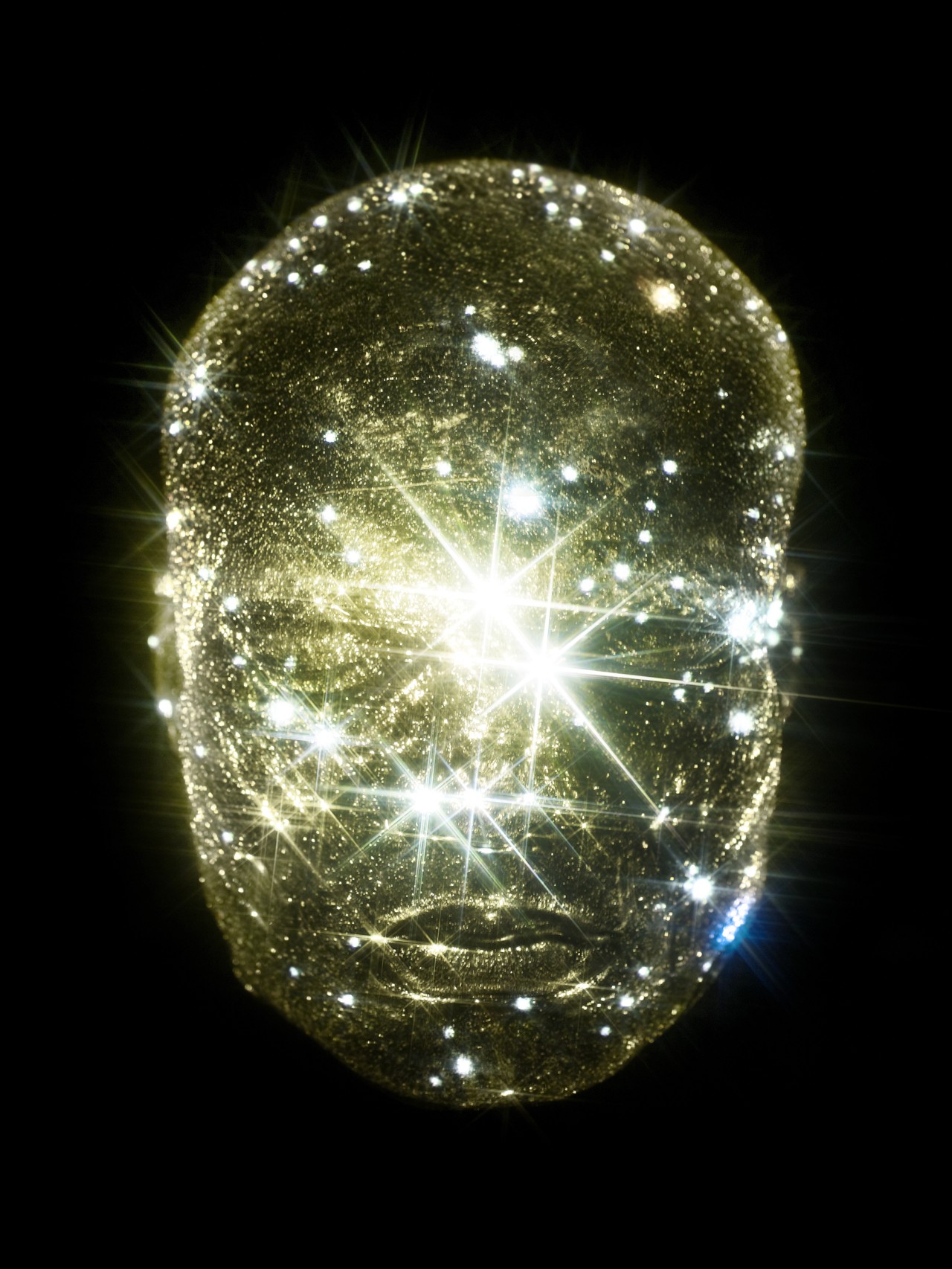

Photograph by Rankin / Trunk Archive

words by willow defebaugh

“Life is nothing if not electrical.”

Wherever you are reading these words, however they have found you, you are only reading them because of electricity. And I don’t just mean the kind that powers whatever screen delivered this missive to you. Electricity is more than what illuminates our days, the lightning that flashes in the sky, seemingly so distant from us. You are alive because of electricity— because of the sparks of life coursing through your flesh.

In the right upper chamber of your heart, there is a spark. A small mass of tissue there called the sinus node is responsible for it: the generation of an electrical stimulus. That spark will then travel through conduction pathways and initiate a contraction of your heart’s ventricles, causing them to pump out blood to the rest of your body. Under average circumstances, an electrical stimulus will move through the heart 60 to 100 times per minute—each contraction, a heartbeat.

Bioelectricity refers to the electric potentials and currents generated and conducted within organisms. These can vary from one millivolt all the way to 1,000 volts in the case of the electric eel. These electrical potentials created by naturally occurring biological processes and cells are nearly identical to those created by batteries and power generators, except they involve a flow of ions (electrically charged atoms and molecules) rather than electrons. Our every experience of the world—through sight, smell, sound, and even our thoughts—is owed to electricity.

In his recent book Spark, Georgetown University professor Timothy J. Jorgensen illuminates this: “[Some people] don’t appreciate that electricity is also a biological force, essential to the life of all animals that have a nervous system, and even those that don’t. Many people also are unaware that electricity is really the very foundation of life. It’s the spark that brought the first primitive life-forms into existence and started them down the evolutionary path leading to today’s complex species with sophisticated internal electrical systems.”

All cells have bioelectric potential which they utilize in carrying out the metabolic processes that allow our bodies to function. Certain cells make specific uses of these currents for designated biological responses. For example, nerve and muscle cells use electrochemical pulses to communicate and discharge currents along nerve fibers in order to stimulate the contraction of muscle fibers. It is electricity that moves us—a common current we share with other animals.

Of course, other animals have developed more remarkable ways of interacting with electricity. And it’s not just the electric eel; an estimated 350 species of fish can generate currents of 860 volts (by comparison, the shock you receive from an outlet is around 120). Sharks detect the electric fields generated by muscle movement to hunt for prey, as do platypuses and echidnas. Meanwhile, bumblebees use the electric fields created by their wingbeats to alter the static electricity of flowers to let other members of their hive know a flower is out of pollen.

We are electric beings—columns of water conducting neural signals and electromagnetic impulses, containers for chemical reactions we may never fully understand. If you place your hand over your heart, you can feel it there: the evidence of that electricity in every beat. Like conduits of a force far more powerful than we are, it connects us to the wider realm of life, to each other. What do we feel when we meet someone who makes us come alive if not a spark?

I Sing the Bioelectric