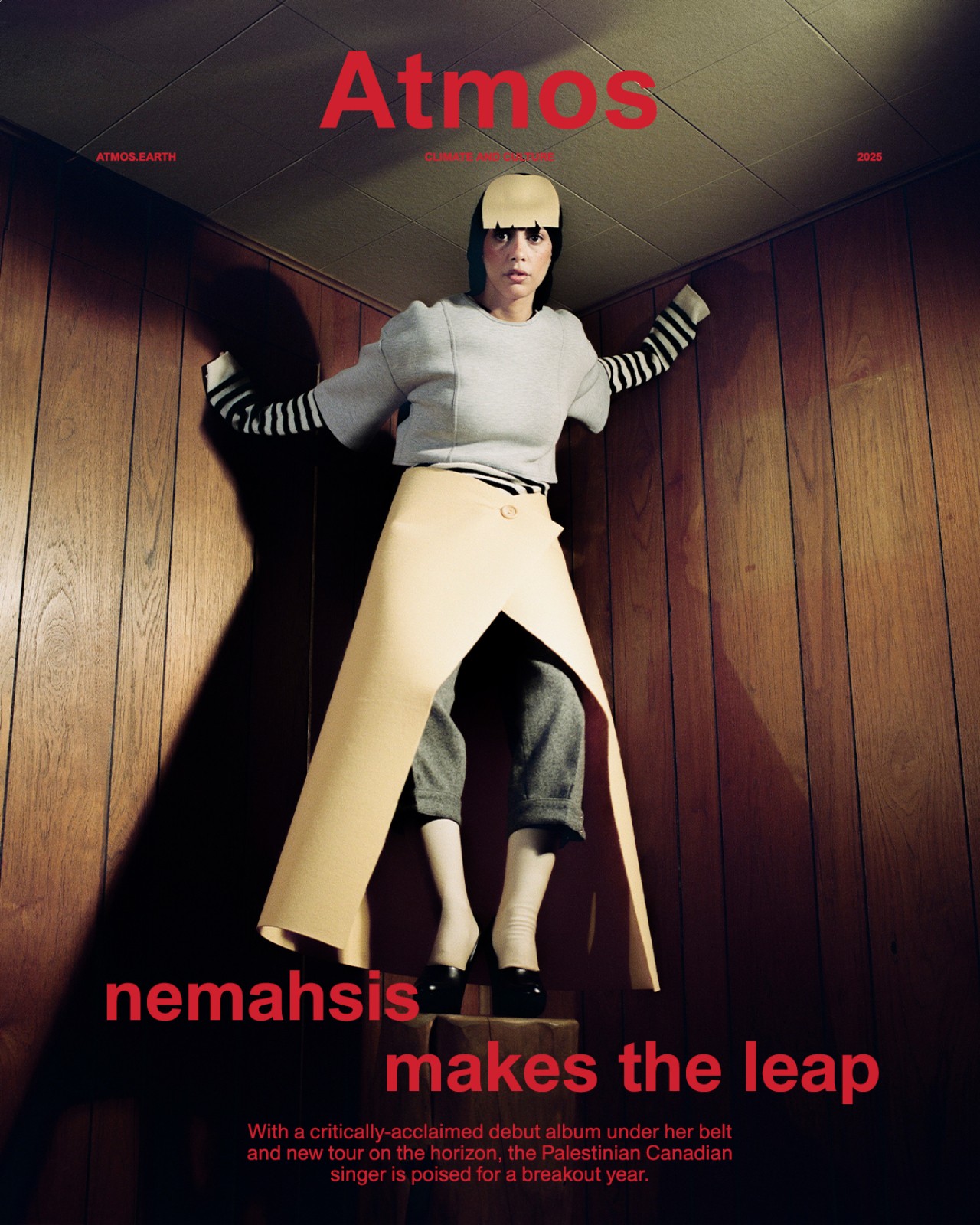

Dress from Sixnineosix, skirt from Rick Owens, stylist's own earrings

Words by Dalia Al-Dujaili

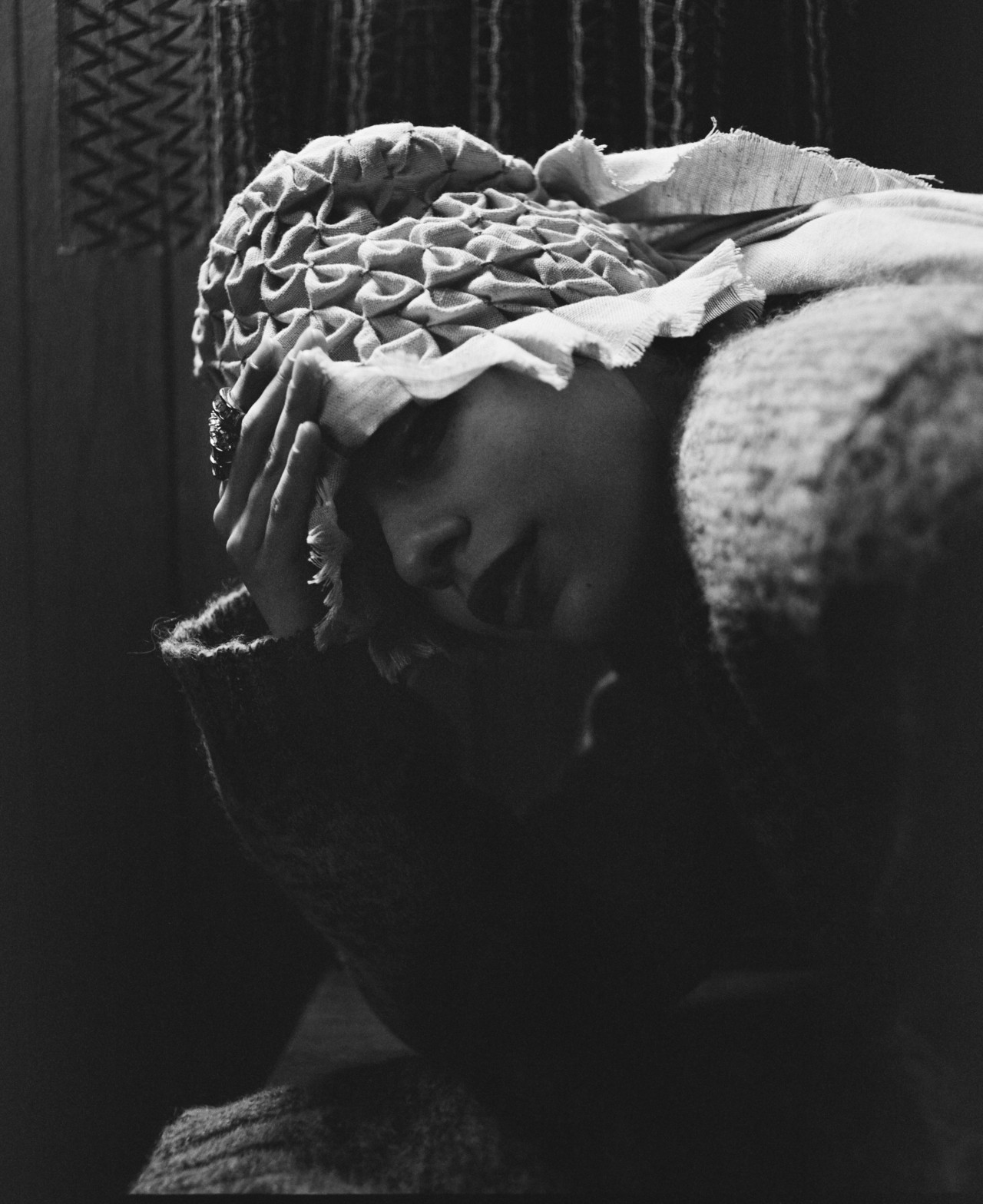

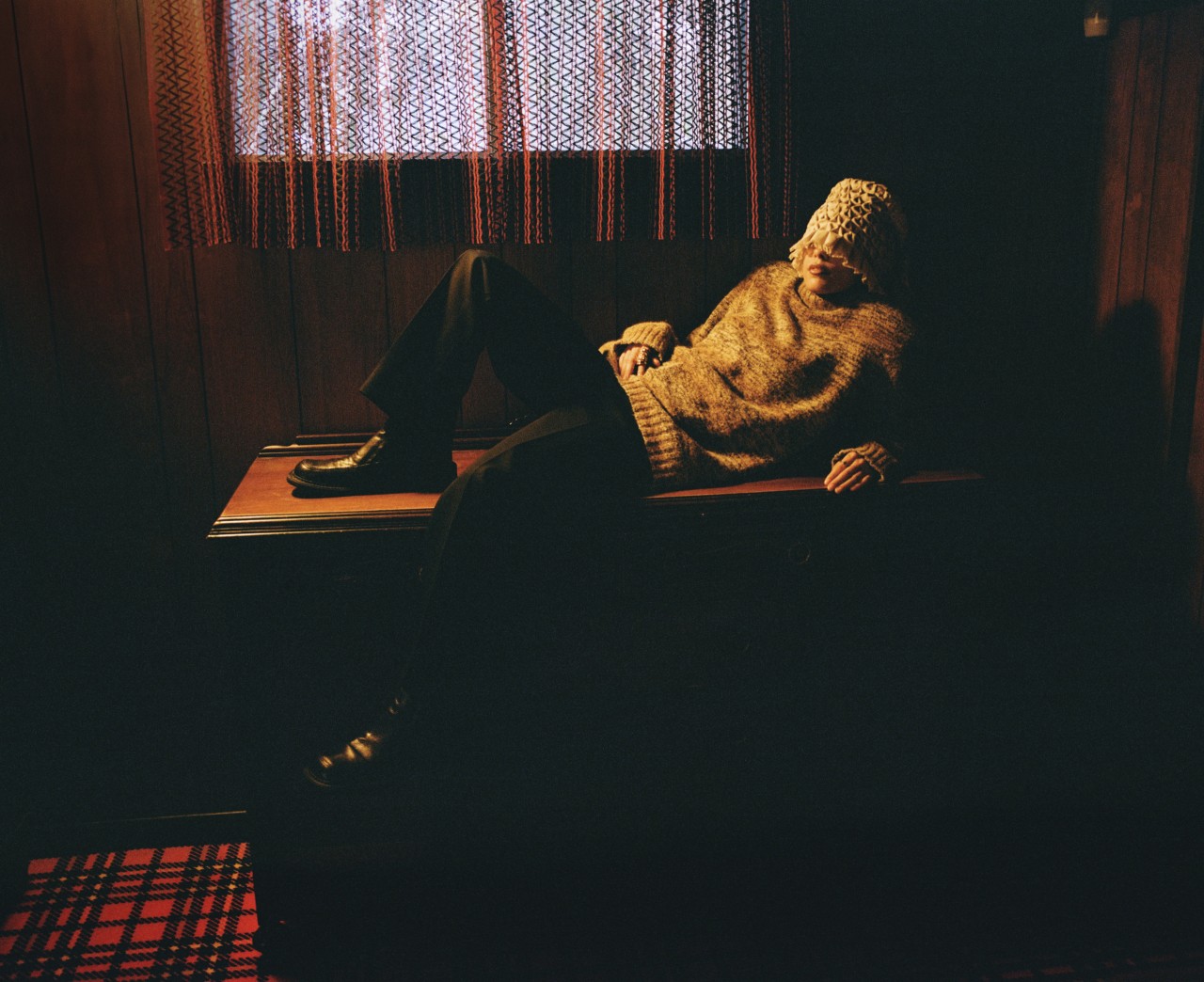

Photographs by Kennedi Carter

When Nemah Hasan video calls me from her family home in Toronto, Canada, she’s quick to tell me she’s a Pisces “like Kurt Cobain,” she says, before turning the phone to her chickens, who are running around her car parked out front. Hasan, who is better known by her stage name, Nemahsis, is a self-proclaimed “farm girl;” she also happens to be one of the globe’s fastest-rising pop stars. We’re soon talking about what we have in common—and though I’m not a farm girl, per se, I do share Hasan’s semi-rural upbringing, both of us sticking out as visibly Arab women during our adolescence.

Hasan had a breakout year in 2024: She released her viral single “stick of gum” in the spring, which catapulted her onto the global stage with half a million views on TikTok; received the fan-selected Audience Award at Canada’s 2024 Prism Prize for her music video “i wanna be your right hand;” and put out her highly-anticipated first album, Verbathim, as an independent artist, which was met with critical acclaim. Though Hasan has been a TikTok sensation for some time, having amassed 1 million followers even before the release of her first single, it was the last 12 months that also certified her as a core member of the Palestinian diaspora’s global music movement alongside celebrated artists Elyanna and Saint Levant (both of whom are friends and supporters of Hasan).

2025 promises to be bigger and better with the singer’s first United States tour starting later this month, called “don’t go where you’d hate to be found.”

But navigating a historically exclusive—and at times Islamophobic and misogynistic—industry hasn’t always been straightforward. A few days after October 7, 2023, when Hamas-led militant groups launched a surprise attack in southern Israel, Hasan says she was dropped by her label for her outspoken support for Palestine and criticism of Israel’s all-out invasion and destruction of Gaza in response to the attack.

Hasan had begun work on Verbathim in late 2022. To finish it independently—and without the money she had been expecting at the time of its release—she had to rethink the release strategy she’d planned. “I did the absolute very best I could have done with the little bit that I did have,” Hasan says. “I can’t believe I was able to execute as much as I did with what I had.” Despite the odds, Hasan made it happen; the result is as much a discerning first album that spans themes and genres as it is a testament to dreams and determination.

Hasan is lyrically clever and endlessly witty. Verbathim is the perfect example of her range. Her frequent word-play exposes the double standards against hijabi women as does her self-stylization. For the cover of Verbathim, she chose to wear a traditional nun’s head covering called a wimple. And in the song “you wore it better,” she sings about the painful ordeal of trying to appease Western beauty standards: “Don’t get close, you’re gonna hate me / you chose how you want to see me / they’ll look cool on anyone but me.”

In “stick of gum,” Nemahsis laments: “I swear if I showed you a song I made you’d say it’s not your taste / If anyone else but me wrote it it’s a masterpiece.” The sentiment echoes an earlier single called “i’m not gonna kill you,” in which Nemahsis sings her listener would like her better as “an Emma,” a Westernized spin on the name Nemah. The lyric “feels so silly” to Hasan today, she says, “because it feels so little compared to so many things that we’re going through right now.” But “when something ages like that,” she continues, “I think it means we’ve made progress.”

She often wears the hijab in playful, creative ways, but never tokenizes nor trivializes the traditions of her faith. In the video for “criminal,” she wears a latex head covering, and in “i’m not gonna kill you” she sports chainmail, an ironic nod to the title and an inversion of how Islamophobic tropes portray Muslims—and especially Palestinians—as violent, conflictual aggressors. The metallic hood also serves as a symbol of Hasan’s strong sense of self-defense. “I think I really understand silhouettes,” she says. “I don’t care about how my body looks in the clothing and I don’t care about feeling sexy or pretty. Hijab really helps with that because you detach from using clothing as a tool to feel more desirable. [For me,] I became less of what a body is supposed to look like [as] a woman.”

“I think hijabis are the biggest chameleons walking on Earth. We have to learn how to maneuver through spaces, how to read a room, how to be more or less visible, how to be invisible.”

Though Nemahsis has become an inadvertent modest-wear style icon for many young women through her reimagination of hijab at a time when modest wear is in its renaissance, Hasan is hesitant to call herself “stylish.” She’d go so far as to say she’s “not a tasteful or fashionable” person. “People look up to the courage it takes to wear whatever [you want],” she says. “And people believe that it’s fashionable because of the person wearing it.”

Hasan’s recordings detail, in complex metaphors, the bullying she was subjected to as a girl and the pressures she was under for being who she is. “I got bullied for the way that I dress up until I started releasing music,” she says. “But this way of dressing has always been what didn’t make me friends and got me depicted as the weird girl.” These memories of attending school in Canada are what inspired “coloured concrete,” a remedial ode to the beautiful wakening from an adolescent haze of not feeling good enough—not feeling that you belong—as anyone who grew up “different” knows all too well.

“I think hijabis are the biggest chameleons walking on Earth,” Hassan says. “It’s a survival mechanism: We have to figure it all out quickly. We have to learn how to maneuver through spaces, how to read a room, how to be more or less visible, how to be invisible.” In her music videos, Hassan plays multiple characters, transforming her appearance to blend in seamlessly with her environment. “People take years and years to try new things and shift between genres,” she says. “But I’m so used to switching and maneuvering [after] 20 years of wearing a hijab—it’s only natural it happens in my sound as well.”

The only constant throughout Verbathim is the diversity. The album is a palate cleanser and antidote to boredom. Throughout, Hasan keeps listeners on their toes by switching sensibilities not only between songs but between seconds within the same song. Hasan does not like spoken word, she tells me that definitively. So, it was a surprise to her and her listeners to hear spoken poetry on “spinning plates,” a song about self-realization and reflection. “It just came out like that,” she says. A digression from “stick of gum,” which is an eruption of joy and celebration, she says “spinning plates” is “the most truthful, courageous thing I’ve ever done.”

The crowning jewel of Verbathim is undeniably “stick of gum,” Hasan’s love letter to Palestine.

The music video, which went viral, was filmed in Hasan’s hometown of Jericho in the Palestinian West Bank during a family visit just as the Israeli bombardment of Gaza intensified. “I needed to feel alive again,” Hasan recalls after months of watching the genocide worsen from her phone screen. She was feeling depressed in Canada, so decided to travel home to Palestine to visit family. “At the time I didn’t understand how much I needed that,” she says. “But I probably wouldn’t be here today if I hadn’t gone.”

When Hasan’s creative team decided to shoot the video during her time in the West Bank, she knew exactly what she wanted to capture. She would run through Jericho’s streets with local kids, she told director Aram Sabbah, and lean out of a moving car, screaming. But, despite it being her most pertinent emotion, Sabbah advised her to put the rage aside. “He said that the video needed to take a loving point of view because that’s how everyone is [in Palestine],” she says. “All we’ve been seeing is Palestinians dehumanized.”

Today, “stick of gum” is Hasan’s favorite video because she’s barely in it. “It’s not about me,” she says.

Instead, the video features her family members alongside locals from Jericho simply living their daily lives. It opens with a close-up shot of a woman at home in a quiet moment of reflection before panning left to Nemahsis singing to the camera. As the verse leads up to the chorus, the camera shows more of the neighborhood and cuts to a young boy smiling on a moped. The chorus, then, erupts in joy, giving way to tender moments of everyday life in Jericho. Throughout the song, Hasan is depicted leaning out of a car window, yelling her lyrics with radiance, before cutting to shots of her running alongside boys, full of an energy that one feels among people of the homeland. “It’s peak artistry,” she says. “I feel that it truly is the best video of the decade. I don’t think anything has made anyone feel that way [before]. It’s the best song I’ve ever written.”

Releasing the video for “stick of gum” was a balm for Hasan, and for viewers across the world.

This period has been filled with complexity, Hasan says. She struggles with releasing music during the Israeli genocide in Gaza, but she knows that her music is healing for listeners advocating for a free Palestine. It’s also an act of resolute determination. She’s been forced to navigate an industry on her own that is largely silent on Palestine, and Hasan’s words—her commitment to speaking truth to power—is nothing short of creative resistance. Music is the only thing that soothes not only her aching heart, but ours too. That and her faith in God.

“I wouldn’t be here right now if I didn’t have my beliefs; if I didn’t believe that He knows best,” she says. “I really put my trust in God.” When Hasan was dropped by her label, she was in a dark place. She didn’t understand why she was dropped—and she still doesn’t. “But the bigger picture reveals itself bit by bit every day,” she says. “I don’t know what I would do if I didn’t have my relationship with Allah. I wouldn’t be the artist I am. I don’t even think I’d be alive right now, honestly. That’s the truth.”

Looking to the year ahead, she is focusing on her U.S. tour. After that, she hopes to tour Europe and the Middle East. But there’s no doubt that her journey has been—and remains—filled with uncertainty, fear, and grief. Being an independent artist, Nemahsis worries about how to fund her creative projects and relies heavily on support from the community. “It’s really scary when you have absolutely nothing,” she says. “Streaming doesn’t make money. People think artists make money, but I’ve not made money in two years. I think every person knows what it feels like to bet on themselves, [only] some people can bet more than others.” And with Israel’s continued aggression on Palestine, Hasan fears for the safety of her family in the West Bank.

She wears her pain on her sleeve, since the death count is still rising.

Nemahsis embodies superpowers like shapeshifting and invisibility, but she is also filled with a righteous rage; a powerful need to tear apart the status quo only to rebuild and create anew. Hasan’s rage, born from a deep love for Palestine, is as much a creative force as her music. It drives transformation and truth in her artistry. Never has this been more urgent.

As Nemahsis the artist continues to use her ever-growing platform to stand up for justice, Hasan the woman says she is still figuring it all out—with grace.

Production Dasha Khomenko Production Assistant Scott Savoy Styling Lilyana Khoshaba Styling assistant Toleen Abdulhamid Makeup Emma Caratozzolo Video Anyo Photography assistant Sloane Bartley

Correction,

January 7, 2025 11:18 am

ET

The spelling of the names Aram Sabbah and Emma Caratozzolo have been corrected

Nemahsis on Palestine and Singing Truth to Power