Words by Isabel Alarcón

Photographs by Camila Falquez

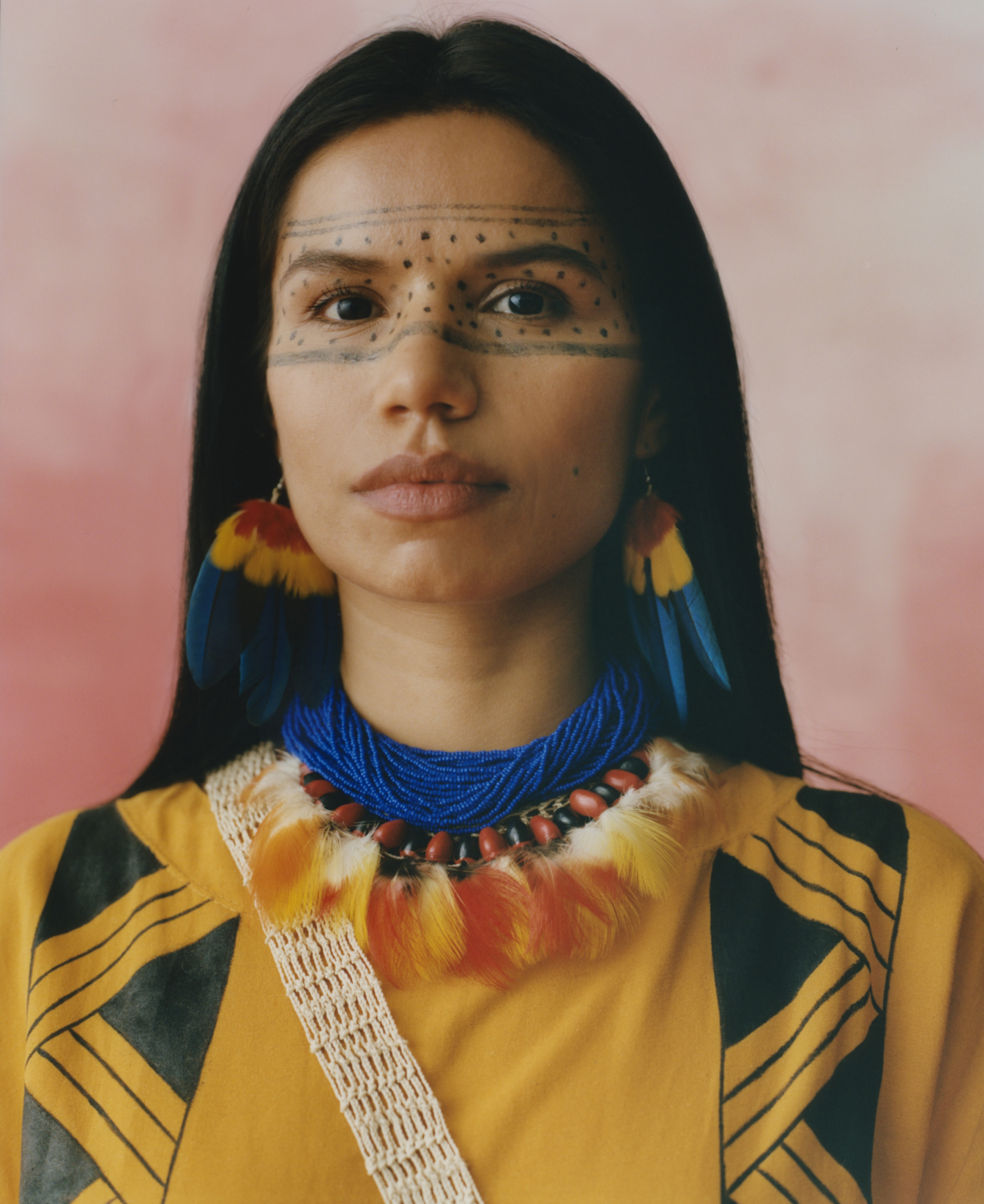

From Helena Gualinga’s perspective, the rainforest—not just the individual plants, animals, and fungi that comprise it, but the rainforest as a whole—is a “living entity.” Helena is a member of the Kichwa community of Sarayaku in the Ecuadorian Amazon, who believes that every tree, waterfall, creature, and human being living in this ecosystem are interconnected and dependent on each other.

Her community lives in the middle of the jungle, in an area that can only be reached by small plane or boat, where 90% of the primary forest is still remarkably intact. The lack of roads connecting them to urban areas has allowed the Kichwa to preserve their forest, their rivers, and their culture for centuries.

“My childhood was surrounded by nature. I grew up playing in the creeks, listening to the sounds of animals in the jungle, harvesting the chakra, and living in community,” said Helena. (Chakra in this context refers to an agroforestry plot.) “We had a peaceful life, but you could feel in the air that there was something that worried the adults. That world that I lived in as a child—which was like a perfect place to me—at some point I started to be afraid of losing it.”

As in other areas of the Amazon, the equilibrium began to shift as extractive industries set their sights on exploiting the territory’s resources.

Nina Gualinga, Helena’s sister, remembers her first act of resistance against the destruction of the rainforest: not accepting an apple from an oil company worker. When she was eight years old, an outsider approached the community’s children with a bag of fruit. Apples were not a common product in her territory.

“Although I wanted it very much, I felt that if I accepted it, I was betraying my people,” she said. Nina had been accompanying her mother to the community political assemblies since she was a baby and was not going to be won over that easily. “I wanted to scream at him to go away and not to destroy this place, which was my home,” she recalled later. But her throat had closed up and no words would come—only tears.

Now, her voice, and Helena’s, are heard in Ecuador and beyond its borders, via international conferences and climate summits, as well as through their social media networks, where they have a combined 215,000 followers. The sisters, at ages 30 and 22, have become internationally recognized for their role in fighting for the protection of the Amazon, becoming fixtures at climate strikes in New York and the United Nations Climate Change Conferences (COP).

In spite of their global recognition, what has not changed is their refusal to accept “apples” from extractive powers.

“If we do not fight for the Amazon and allow them to continue destroying it, our rainforest will die and lead to the disappearance of our beliefs, spirituality, culture, and wisdom.”

Oil drilling began 50 years ago in the Ecuadorian Amazon and it hasn’t stopped since. In 2023 alone, oil exports in Ecuador generated nearly $9 billion; pipelines along the main roads are now part of the landscape. In the best of cases, oil is transported uneventfully through these pipelines. But all too often, it spills and contaminates the land, water, and air—according to emails from the Ministry of the Environment, there are two oil spills in the Ecuadorian Amazon every week. In addition, mining territories have grown by 300% in the last five years, and hydroelectric dams are emerging as a new danger.

These extractive activities are gaining ground in an area that’s home to 11 of the 14 groups of Indigenous peoples living in Ecuador and thousands of species of flora, fauna, and funga. Inhabitants often do not benefit financially from the oil their region produces. The provinces in question have the highest levels of poverty in Ecuador and the least access to basic services like water and electricity. In Pastaza, the province where Sarayaku is located, 65 out of every 100 inhabitants are considered poor.

But history shows that when these communities fight back, sometimes they win. In 2002, the Argentine oil company Compañía General de Combustibles (CGC) entered Sarayaku despite community opposition. In the land the Kichwa call home, more than 3,000 pounds of explosives were buried to extract oil, communal spaces were invaded by the military and foreigners, and the living forest was cut down. After years of protests in their territory in the face of violence and harassment, the Kichwa filed a case with the Inter-American Court of Human Rights in 2003 asserting that the Ecuadorian state had granted a private company permission to enter their territory to extract oil without the community’s consent. It took almost a decade before the court handed down its judgment.

Nina remembers accompanying her elders to the Court in Costa Rica in 2012 in the midst of that process. “I cried every day listening to the lies of the Ecuadorian state. They said that the military never mistreated the community and that there was no violence,” she said. While she was in court, her sister Helena watched the public hearings from Sarayaku. The internet had just arrived to the community and the signal was cut every 10 minutes, but everyone crowded into a room to follow the process.

Ultimately, the Court ruled in the Kichwa’s favor in June 2012, setting a new precedent for the rest of the country.

Witnessing that process helped shape the Gualinga sisters into the fierce environmental defenders they are today. It propelled their involvement in what became another newsmaking victory this year: Both played a significant role in rallying Ecuadorians around the historic decision to halt oil drilling in Yasuní National Park. Last year, 60% of the country voted in a popular consultation in favor of stopping oil extraction in this protected area, which is one of the most biodiverse places on Earth, with more tree species than the United States and Canada combined.

Despite these achievements, threats to the Amazon persist. If deforestation continues at its current pace, scientific studies indicate that in less than 10 years this region could reach the point of no return, where the process of tree die-off continues even if humans aren’t actively destroying forest. If that tipping point is reached, much of the Amazon will become a savanna with a lower capacity for storing carbon. If the Amazon is destroyed, it won’t just impact the communities that live nearby; its role in the global climate system means that the ripple effects will be felt in every corner of the world.

The advance of extractive activities has not only renewed the Gualinga sisters’ commitment to fight for their home, but also inspired a growing Indigenous youth movement in the Ecuadorian Amazon. More and more new voices are joining the chorus to make themselves heard both at home and abroad.

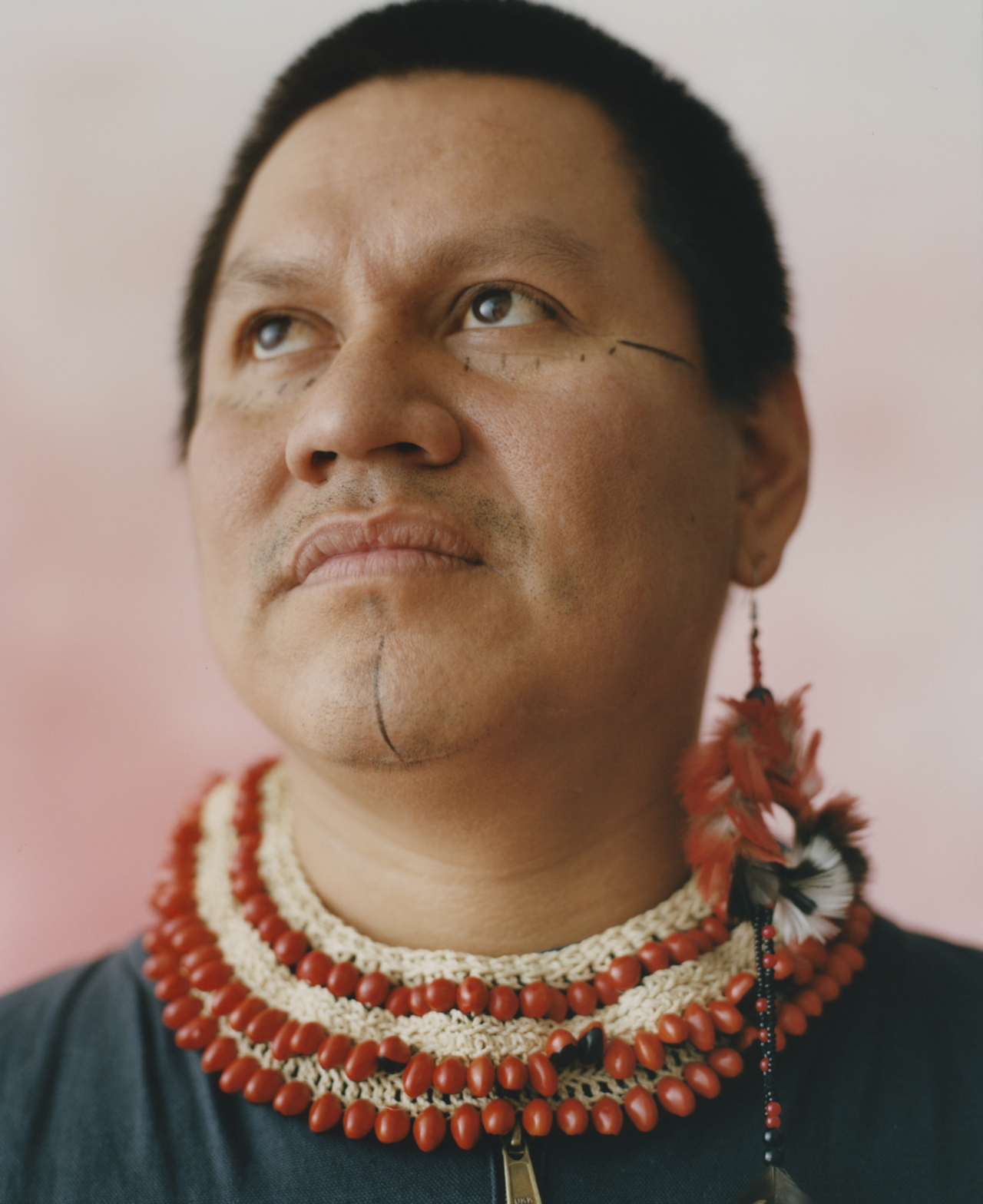

Leonardo Cerda, who hails from the Serena community, is another young Kichwa leader who has dedicated his life to promoting the conservation of the Ecuadorian Amazon. Although his journey as a forest defender was sparked by seeing the impacts of the oil industry in the northern Amazon, his current focus is on mining.

According to data from the Monitoring of the Andean Amazon Project (MAAP), an initiative of Amazon Conservation and EcoCiencia, 13,877 acres of forest have been converted to gold mines between 2015 and 2021—the equivalent of 10,555 professional soccer fields.

Cerda has lived with the impact up close. Napo, the province that the 35-year-old was born in and calls home, has seen mining increase 316% in five years, making it the hardest-hit province in the country. Along the Jatunyacu River, mountains of soil mined from the ground can be seen piling along the banks. Over time, those mounds of dirt flow into the river and can even change its course. Though using mercury in mining has been illegal since 2015, that hasn’t prevented its use, and mercury also ends up in this water, which the nearby communities rely on for drinking and bathing.

Cerda says that the problem began during the height of the COVID pandemic, when large machines were brought in to extract gold. In 2020, the Ecuadorian government granted concessions for more than 17,606 acres to one company that occupied more than 30% of Napo.

Cerda used social media to spread information about the impacts of this activity in an attempt to pressure the authorities to act and engaged in community organizing to protect the territory. He and other Serena inhabitants have created collectives, such as Napo Resiste, of which Cerda is the spokesperson, and Yuturi Warmi, which is the first Indigenous women’s guard in the Ecuadorian Amazon.

Last year, Cerda and Napo Resiste joined a coalition that included the Federation of Indigenous Organizations of Napo and the local governments in filing for a protection against illegal mining with the provincial court of Napo. The court ruled in their favor, recognizing a violation of the rights of nature and establishing remediation measures as well as rules to carry out sanctioning processes against eight mining companies.

“Community isn’t just about people; it’s about the land that has shaped us. Our way of life is threatened as our elders pass and forests fall.”

“We, as young people, are at the forefront of the defense against mining practices that devastate our territory,” said Cerda.

Another of the tools he uses to fight extractive activities is fashion. In 2016, he created Hakhu Amazon Design, a social enterprise that employs more than 30 women from Serena to manufacture jewelry and clothing that represent their culture. He has trained another 200 people from nearby communities and has shared this model with other Amazonian leaders so that they can replicate it.

The initiative is meant to offer an economic alternative to mining so that people don’t need to engage in illegal or extractive activities to make ends meet. Plus, it means women no longer need to leave their territories in search of job opportunities and can instead stay in their communities and defend them.

The clothing and jewelry they produce is stocked in stores in Mexico City, New York, Los Angeles, and Quito, as well as online, and Cerda’s work with the brand has taken him everywhere from New York Fashion Week to Art Basel in Miami. Income from sales also serves to finance some of his projects.

Now, Cerda and his group constantly monitor the expansion of mining, hold meetings and workshops to find the best ways to educate their neighbors, and organize actions to remove miners from their territory each time they return. His goal with Hakhu is to amplify his community’s conservation message and give them more resources with which to fight mining expansion.

“The work of resistance, defense and conservation goes hand in hand with the exposure we have had internationally with this project,” he said.

Ecuador occupies less than 2% of the Amazon, but contains 18% of the active hydroelectric dams in the region. Although dams are sometimes lauded as sources of clean energy, their legacy in the region is complicated.

Alexis Joel Grefa became involved in the fight for the Amazon when a private corporation called Genefran S.A. announced plans to build a hydroelectric dam in his community of Santa Clara in 2017. Like other Indigenous youth leaders, Grefa, now 23, had been participating in community assemblies since he was a child and saw the resistance of his elders up close.

The Genefran hydroelectric project, which was to be installed on the Piatúa River, was billed as a source of economic opportunity and development for the Kichwa people. But Grefa realized that the project would damage the community’s main livelihood as well as an important part of their culture—for his people, the Piatúa River, whose crystal-clear waters come from Llanganates National Park, is sacred. Plus, Genefran’s plan to use 90% of the river’s flow meant that the community largely couldn’t use the river themselves, which would mean turning to and depleting other water bodies in the area.

“They were trying to kill the river where I learned to swim, fish, and share with my friends. It was quite traumatic,” he said.

Grefa began organizing other young people in the community into what they called the Piatúa Resists collective. In 2019, the group, alongside other community organizations, filed a protection action for a violation of the collective rights of the Kichwa people of Santa Clara and a violation of the rights of nature with the Provincial Court of Pastaza. The court ruled in their favor, and the company was prevented from building the hydroelectric plant. In 2020, the Constitutional Court selected the Piatúa case to generate binding jurisprudence on the rights of nature. The case is still being analyzed.

These days, the Piatúa Resists collective is monitoring local biodiversity and gathering data that will help them demonstrate the importance of preserving this area. “I want the new generations to feel the river, to feel the stones, and to live and enjoy it as I did,” he said. Since 2022, he has been closely following global climate negotiations and has attended COPs to represent Indigenous voices and encourage others to participate in these events.

The fight for the Ecuadorian Amazon is far from over, but this generation of Indigenous youth is not simply resisting extractive activities; they are building sustainable alternatives and amplifying their message on the global stage.

They are sure that the forest is—and will continue to be—alive.

PHOTOGRAPHY ASSISTANT Stephanie Ayala SET DESIGN Camila Falquez Studio LOCATION Delicia Studio PRODUCTION Lindsay Thompson, LUMIEN CATERING Chef Oscar Riquelme SPECIAL THANKS Luis Rincon Alba

This article first appeared in Atmos Volume 09: Kinship with the headline “Lifeblood of the Amazon.”

Correction,

July 3, 2024 9:26 am

ET

The story has been updated to correct the phrasing of the Kichwa People of Sarayaku, which was previously written as the Kichwa community. Kichwa itself refers to a family of languages, not a singular community.

Meet the Indigenous Youth Defending the Amazon Rainforest