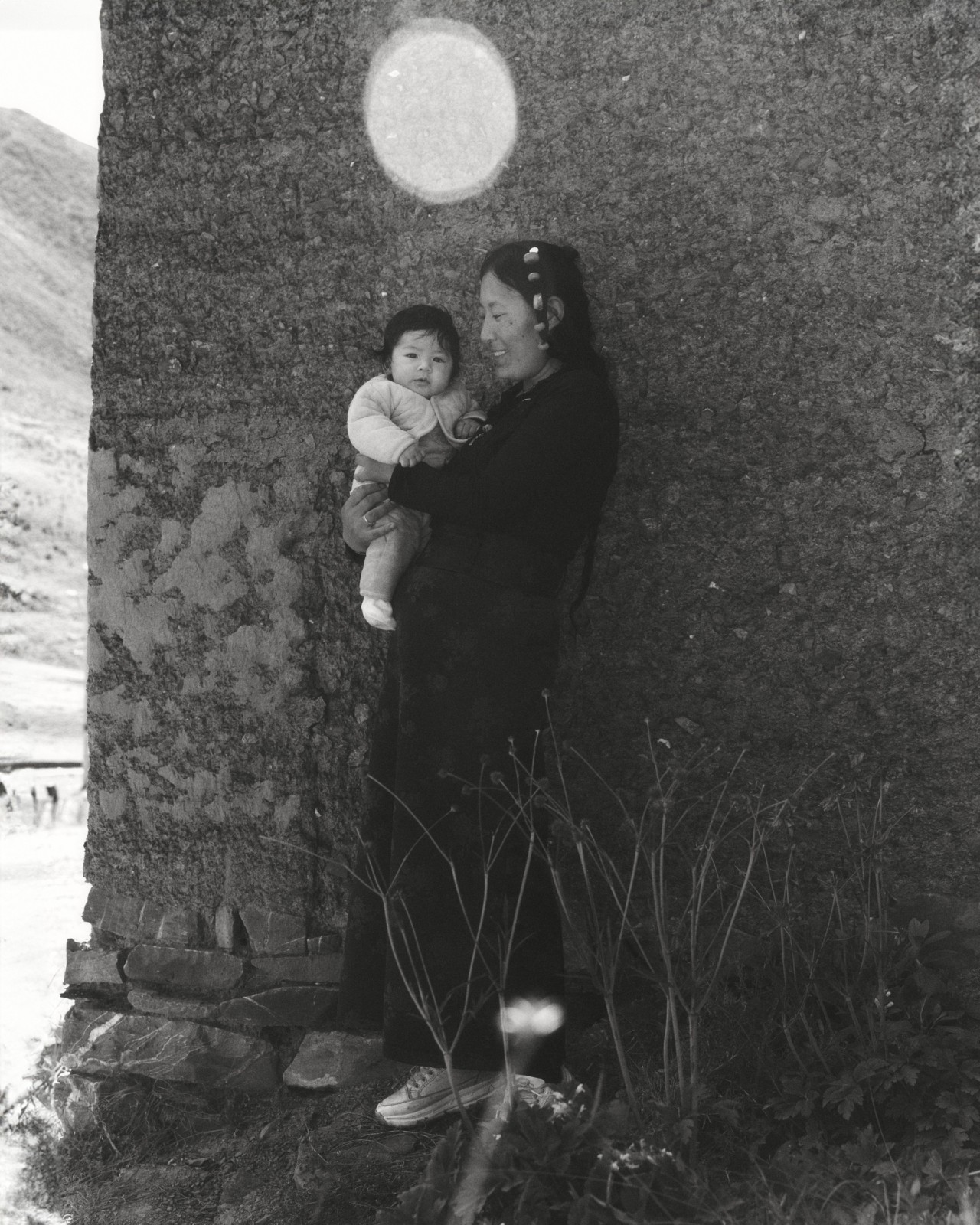

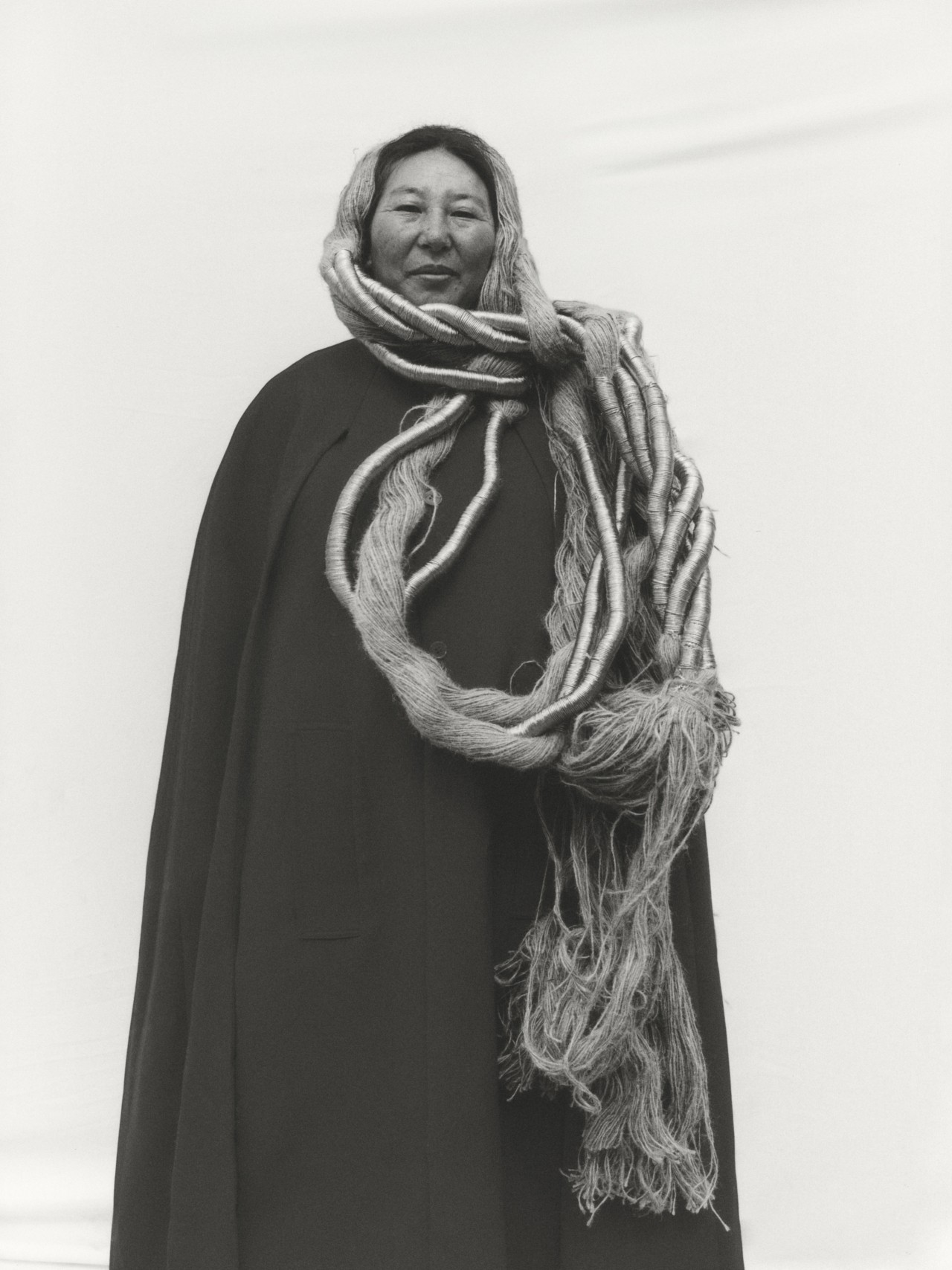

Coat by Louis Shengtao Chen

Willow Defebaugh

This issue of Atmos is about the concept of afterlife. I’m curious what this word evokes for you at this point in your life and in your journey, especially as it relates to your work.

Stephanie Kaza

As a student of the natural world, afterlife is of course the natural cycling of all forms of life from the phases of emergence, growth, maturity, decline and disintegration. We tend to want to favor emergence. It’s very exciting when the seeds sprout in the growth phases, but I think it can be really useful, in ecological as well as spiritual practice, to study the phases of decline.

As a Zen Buddhist, dwelling on the afterlife is usually seen as a distraction from focusing deeply and with full attention on the present. And teachers will call you on this. They want you right here, right now. Because that’s where the opportunities for spiritual liberation and enlightenment are. They’re not somewhere off in your speculating mind. So the practice is focused on arising and passing away in every moment, in every breath. And not on thinking about death as only the end.

Katrina Spade

I fully agree with the connection between the spiritual afterlife and the natural cycle. One of the joys of working with Recompose is literally and viscerally connecting the two things—and being able to create a process by which we’re acknowledging that our corpses can go on to grow new life. So when I think of life after death or the afterlife, I think of what happens to our bodies very physically after we’ve died, and what can happen to them. And there’s lots of choices—or a few choices that are very different.

Stephanie

One of the things I love about Recompose is that you see that time after death in a very relational way. There’s the corpse and then there’s also the family and the friends and the relationships. And I really get the sense that you take care of those, understanding they will change dramatically, but that they can be held in kindness and in compassion and in ceremony. And that is not always the case with standard funeral homes.

Katrina

For sure. I thought that maybe it was a sneaky way of bringing some ritual back into the death practices in the U.S. If I created this new way of caring for the body, then we could go, “Oh, by the way, we created this space and time around that way of caring for the body that encourages ritual again.” Because you’re right, I think with the rise in cremation in the U.S., we’ve seen this coinciding attitude of, “Don’t make a fuss when I die.” That then translates to, “Don’t do anything, don’t even think about it.” Or, “Don’t even mark the moment.”

With this rise in cremation—we’re at 60% in the U.S. now. Whatever you think about the conventional burial systems, they were rituals. Or they are rituals. And then with cremation, the body goes off and you don’t think about it. Unless you have the wherewithal yourself or a faith practice, you may not think, “I’m going to do something with these ashes,” for example, and create ritual. So I do sometimes think that Recompose was a way to both encourage but also kind of reinvigorate the idea of marking that moment.

Willow

Ritual is an aspect of both of your fields, whether we’re talking meditation or funeral rites. How can ritual transform a relationship to both living and dying?

Stephanie

Zen is heavy into ritual. It’s different from the Tibetan rituals which are very culturally influenced and shamanistically influenced. Zen has East Asian influences from Japan, Korea, China, and so on. So there’s a kind of crispness and a clarity to those Buddhist rituals that have a lot of chanting and fierceness to them. I’m a singer: I love singing in choirs, and I’ve been part of a Unitarian Choir, all that. Learning chanting as part of a ritual was a whole different experience, more like doing a martial art. So chanting, bowing, altars, flowers, all the different pieces of ritual are about bringing attention to the fact of and the presence of where you are right now, that arising and passing away.

Stephanie

And it’s all about breaking out of the delusionary bubbles of your individualism, of your immortality, of your exceptionalism. They’re really about cutting through. So ritual at death helps everybody come to the complete awakening. It’s an incredible opportunity for awakening. The time before dying, the time of death, and especially in Zen, the week after death, is seen as a really important time–like in Jewish traditions–to pay close attention to your surroundings, your relationship with a person who’s died by lighting candles or incense every day, doing certain chants. And all of those help you stay with what’s actually happening.

I watched my own mother’s cremation. And I had an associate minister with me and my husband. But I couldn’t get anybody else in the family interested in witnessing that particular moment. We ritualized that by my husband, as an artist, painting the cardboard casket with a scene from the Oregon Coast that she loved. And then I lined the inside with music from Bach’s Preludes and Fugues, which she loved. And then, since nobody else would actually be there with me, I invited people to send notes and prayers, and I put them inside the cardboard. And I folded 84 paper origami cranes as she was dying. So every one of those moments was about, “I’m here, my mother is dying, I’m witnessing this, I will always remember this.” So that’s what I can see ritual does at powerful moments of our experience as human beings.

Katrina

When I started this work, I went back and forth between being comfortable using the word [ritual] and not. Because for a while, I felt like I was saying that in creating Recompose, I would create ritual–and it felt like such a heavy, big thing. But also maybe one person can do that for themselves. There’s a little tension in terms of creating ritual versus what I think we’re doing at Recompose, which is creating a framework for ritual. We’re creating space, both physical and not, to create meaningful ritual.

And this might be, for example, families spending time with their person’s body in what we call “Cedar.” It’s a small room. There’s a really beautiful sink. We have oils and lavender, and usually the person is lying there shrouded. Maybe their face is uncovered, maybe their hands and arms are uncovered. Sometimes they’re fully shrouded depending on the state of the body. And then what can unfold is up to those friends and family. Often it’s a ritual washing, meaning it’s not really cleansing dirt or grime. It’s the act of washing someone as an act of care.

Katrina

Sometimes there’s sitting in silence, which can also be a form of ritual, or prayer. Or sometimes weeping for many, many minutes on end. I think we’ve created a few different places that can feel like a place to try that ritual out. And then in the gathering space, which holds about 30 people comfortably, that’s where the threshold vessel is, which is a portal. It’s a doorway from the gathering space, which is this ceremonial room, into the active composting space, which is where bodies are transforming. And at the end of a ceremony, we pass the body through that portal.

Which, as you pointed out, is a moment of closure. That’s the last time you’ll see that person in that physical form. And what I love to see there is similar to what you did with your mom’s cremation, where people will write love letters—you can compost paper, you can compost hamburgers. Some people got some Dick’s Drive-In hamburgers and placed those around the person’s body. The most beautiful moment was when a person died, and his vegetable garden had just come into bloom or full harvest. And so he had red bell peppers and purple onions surrounding his shrouded body before he was placed into that threshold vessel.

“People need a story to tell around death. If they don’t have a story, they get lost in their emotions, in their grief, and they are swamped by it.”

Stephanie

People need a story to tell around death. If they don’t have a story, they get lost in their emotions, in their grief, and they are swamped by it. Because it’s so new and so powerful. But by gathering in community, they have shared a story together and they can then replay it with each other. And then they can offer it to somebody else. The telling of the story is a kind of extension of the ritual. And that’s the way you let the moment of death move into the past. Together you take the story into the future. You might not know it at the time, but these gathering spaces are really important for creating the story of a death.

Willow

Storytelling around a loved one when they pass is such an important aspect of grieving and moving forward. Ritual provides a container for that to happen. Stephanie, your work grows at the intersection of environmentalism and Zen Buddhism. Could you speak to reincarnation and how you see this framework in relationship to the natural world?

Stephanie

Reincarnation varies tremendously depending on Buddhist lineages, traditions, and cultural contexts. Tibetans place the highest emphasis on reincarnation, because they have experiential evidence over time, over many generations, of the continuity of mind streams between human lives. It isn’t so much that a specific human form suddenly appears again and you see, “Oh, that’s that same person.” It’s that there’s a continuity of the mind stream of the teaching and of the lineage, and then it’s picked up again to be carried in another human mind. The Theravada teachings of South Asia focus much more on making merit and accumulating virtue for better rebirths because you don’t want to have a worse rebirth in one of the animal or hell realms. So they use it as a kind of incentive for good behavior.

Stephanie

In the Mahayana traditions, which includes Zen, there’s much less emphasis on human reincarnation and much more on an enlivened world—a cycling of material and spirit in every aspect of the wider organic and inorganic world. Zen, in particular, is famous for looking at mountains and waters: mountains arising and then eroding and cycling, and the same with waters. There’s a sense that every form of existence is in various stages of becoming and passing away. When you put on that mindset of the fluidity of existence, it’s very dynamic. It’s very energetic. Nothing is still. So this is a kind of teaching to really study that. And you can study your own death and your own existence as a very sharp, relevant, and quite easily available teaching.

A lot of Zen teachings put you face-to-face with the belief that you’re permanent. And to really understand that this key feature of all reality is impermanence. That works very well with the natural world, with an ecological worldview, which studies the cycling of carbon, the cycling of water, the cycling of forests, and is looking now of course at some accelerated processes under climate change, with some ecosystems that are deeply threatened. I’m big on reading geology, so I get the huge perspective of what else is cycled and has been reincarnated. Whole mountain ranges, whole river basins. I try to understand where I live as a total of these processes, of ecological mindstreams, geological mindstreams. Taking the metaphors, the understandings, and seeing them everywhere.

Katrina

So many people come from the conventional funeral mindset—that’s what we know—where you have a burial and then you have a stone with a name on it that’s permanent, forever. One of the things that, from the beginning, I wanted to look beyond was the idea of permanence and the idea of memorialization, which is the funeral industry shorthand for permanence, actually.

And so at Recompose, we are not about memorialization. You can always take that soil and go and create a memorial to your person, but that’s not what we do. And with that comes this educating of what happens, literally, to the molecules and atoms in your body when you are composted. When that compost is used somewhere, what happens over time to those molecules and atoms? We’re always reiterating the impermanence of that. And it’s so beautiful. Yes, we might place you in that forest that is part of our land program. If that’s what you choose, that’s where your soil will go. But it’s not going to stay there. The molecules and atoms will be taken up by that bird and that mushroom and moved through, and soon you’ll be down in Oregon.

Katrina

But it is hard, because people think, “Okay, death. I need my name somewhere. It should be carved on a stone. That stone will be somewhere permanent.” Which of course, isn’t even really a thing. To me, that idea of impermanence is comforting. When you talk about geological time, I immediately go, “Right, there’s a bigger time that gives me comfort because I can move out of it and not worry so much about the human experience.”

Willow

There’s a beautiful quality of dynamism in what both of you are sharing: death not as something static. Even when we think of having gone through this transition, even after that, we continue to transition. It’s just becoming part of a sort of continuous movement as opposed to how we often talk about—or rather don’t talk about—death in the West. Katrina, in that vein, I’ve heard you say before in your work that nature is really good at death. What can nature teach us about the art of dying?

Katrina

When I started thinking about this, I was in graduate school for architecture, which meant I had the luxury of time to think about mortality and death. I knew that I personally didn’t want cremation or burial. Cremation felt too final and a bit wasteful of whatever I have left in my body when I go. And then burial in the conventional way to me, felt toxic—and the embalming and the extra stuff in the ground, it felt again wasteful.

So I was drawn to natural burial, which is where the body is placed in the ground with a shroud or a pine box. It used to be the way everyone did things. It’s still practiced all over the world. But in the U.S., conventional practices have moved away from it. So I was like, “Well, natural burial, how perfect is that? You give your body back to the earth and let nature take it back.” But it struck me that you need land for natural burial. So maybe it’s more of an appropriate solution for rural settings. And so I started to think, “Okay, what can we have in the city?” I love living in cities, so I want to stay here after I die. How could I stay here and be part of nature in the city?

“What I’ve really learned is that these aren’t opposites. Death and life, it’s all one process. Death is happening all the time. Life is happening all the time.”

Katrina

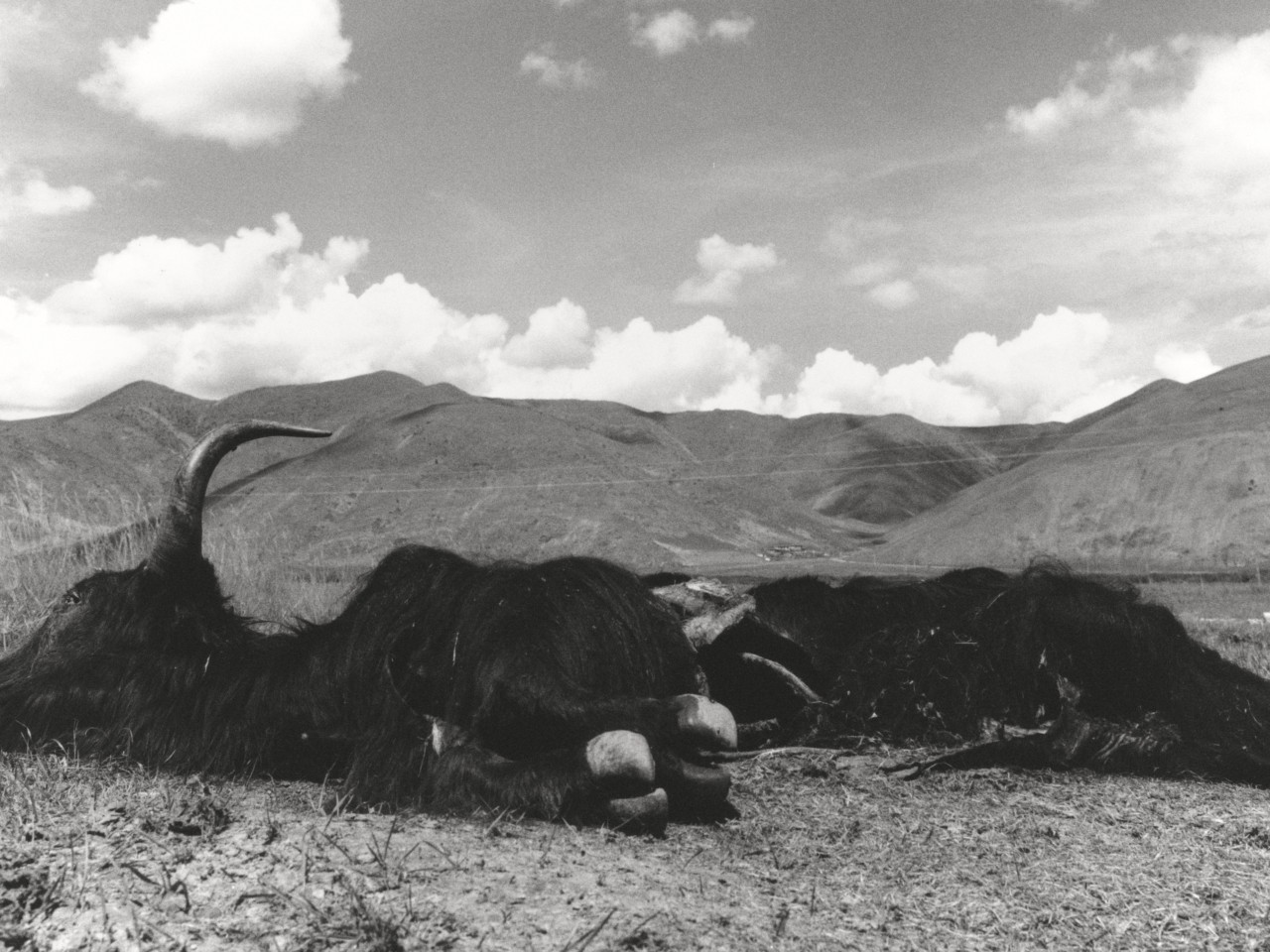

I was thinking a lot about what nature is. So I was thinking about trees and forests and moss…and then it occurred to me that actually the basis for all of that, of nature, is this decomposition process creating soil and the decay of organic materials creating new life. And I just got obsessed and stuck on this beautiful idea that nature actually is decomposition and death. Maybe it does it well, or maybe it is those things.

Willow

Both the way that we live and also the way that we die deeply impacts the health of our planet. In what ways do you see your work as connected to a solution to the climate crisis?

Katrina

I do want to say that I actually believe there’s room for every death care practice. We’re not going to prohibit cremation if it’s part of your cultural, faith tradition. If it’s meaningful to you even, if fire is something you love. Same with embalming. I love that because it’s an intentional choice.

That said, for the millions of people who are choosing cremation as sort of a default, I would love for human composting to be that default–where you’re not necessarily even thinking about making the choice. It’s the obvious choice. So what we’ve calculated is that when you compost someone instead of cremating them, by avoiding the emissions of cremation and also through the sequestration of carbon during the process, it’s north of a metric ton of carbon per person that is saved.

Katrina

But for me, honestly, what I think might be a bigger impact of bringing human composting to the world is that it actually may be more about the connection that we are able to find with nature when someone we love goes through this process. And if all of us or many of us go through that process with a loved one and start to really have crystallized the fact that we are part of nature, then I think that the care of the world and the care of the climate will follow that. So the power may be less in the carbon savings and sequestration than in the shift in how we look at ourselves.

Willow

Stephanie, we’re seeing so many people turning to Zen Buddhism as a path to navigating such transformative times. In your eyes, how can spirituality assist us with navigating a world in transition?

Stephanie

I think what’s attracting people to Buddhism for spiritual strength and for support is the centering on compassion and wisdom. We’re suffering with so many things—the opioid crisis, the climate crisis, et cetera, et cetera. Just being a human being is filled with suffering. And the Buddhists start right there. You’re going to be sick, you’re going to die, you’re going to be filled with desire, you’re going to be a consumerism addict. They just say, “This is what you’re made of. It’s what drives life. Going after a mate, going after food.” So learning about that, but with compassion, not with judgment.

Definitely compassion and some of these centering, calming practices–like meditation, chanting, and bowing–people find them restorative and centering. I also think at the center of some of the Buddhist lineages is an emphasis on skillful means. And I apply that concept to activism. It means that there isn’t one single right way that works with the same audience all the time. And the “skillful” part means you’re acting from compassion and wisdom. You’re not acting from us and them, you’re acting with an intelligence about what’s arising in that situation.

Stephanie

People need a sense of belonging. So if they can go to a meditation group—even online, once a week—they’re finding some sense of belonging. We really need that in this world that emphasizes individualism so much. We’ve been left in this pandemic of loneliness after COVID. And at the heart of this practice is a kind of relief from the oppression of self-centeredness, of being so absorbed with our life, our details, our habits, our neuroses. I think Buddhism works in helping people stabilize their minds and stabilize their capacities to offer something to the world. And people want to do that. They want lives of meaning. And this is one path that can take people to that.

Willow

What is one thing that death has taught you both about life?

Katrina

Memento mori: “Remember that you will die.” It’s so trite, but life is so short as we’re experiencing it now. And so I really just try to be as present as possible each day.

Stephanie

What I’ve really learned is that these aren’t opposites. Death and life, it’s all one process. Death is happening all the time. Life is happening all the time. Certain parts of my body are surging forward full of life, and others are clearly in decline. So I look for that in the forest. I look for that whenever I’m out in the natural world. It’s a practice to see things this way, down to that sense of beginnings and endings arising and passing away in every single moment. So if you want some spiritual practice to rest in, pay attention to what’s arising and what’s passing away in every microsecond.

PRODUCTION Sufi Sun STYLING ASSISTANT Monica Liu, Dollking, Anna Ye MODEL Sorentsomo DARKROOM Perfect Print

This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

This story first appeared in Atmos Volume 10: Afterlife with the headline “Beyond the Grave.”

Katrina Spade to Stephanie Kaza: What If Nature Actually Is Death?