This story is part of a two part series. Read its companion story, Bayo Akomolafe on How to Make Sanctuary in Times of Loss.

Words by Jazmine Hughes

Photographs by Eric Gyamfi

Content warning: graphic descriptions of racial trauma, slavery, and violence.

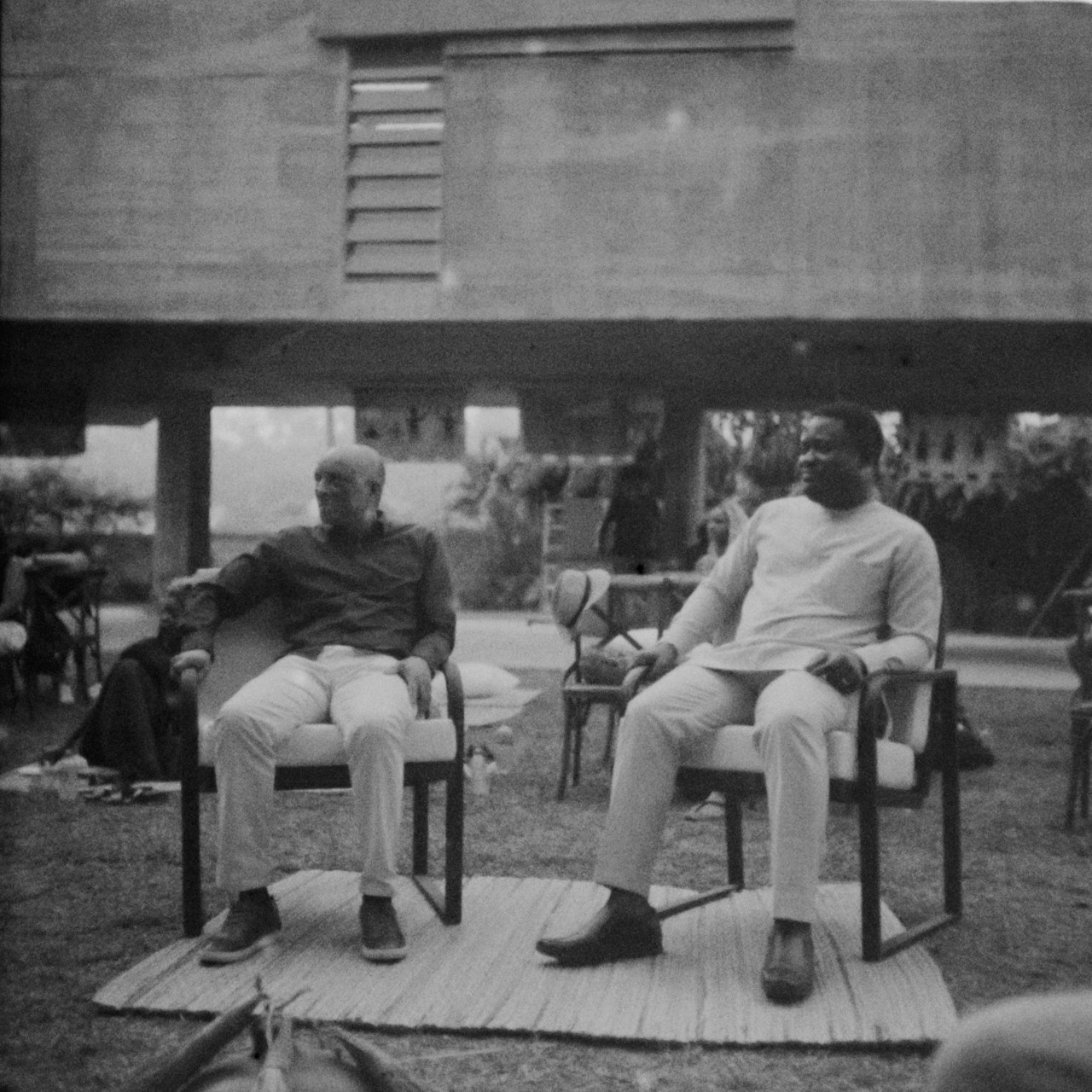

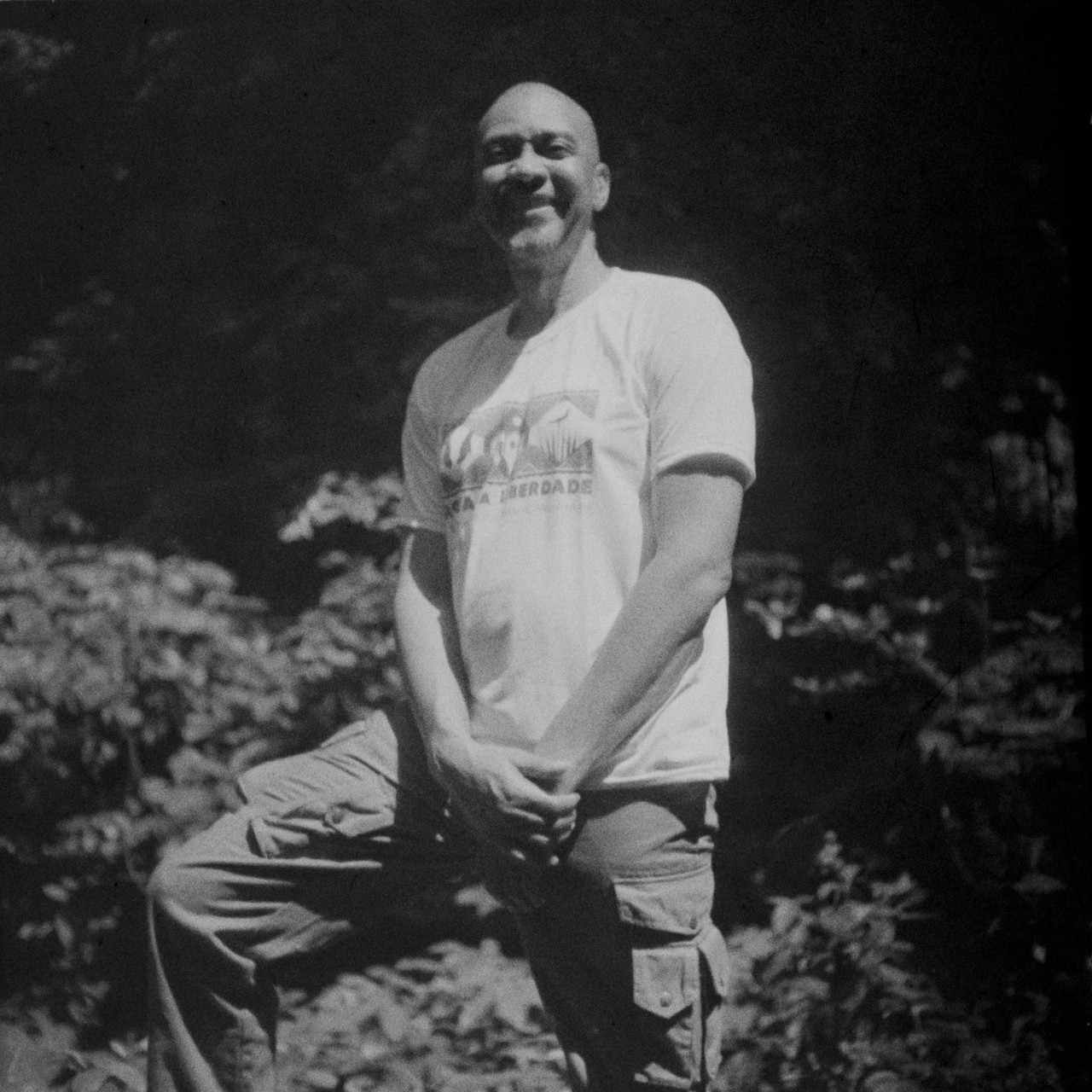

In the clearing of the garden of the Nubuke Foundation in Accra, Ghana, Resmaa Menakem, Bayo Akomolafe, and Orland Bishop settled their bodies into plush, wide chairs, their faces slick with anticipation and evening sweat. The subtitle for their gathering was “trauma, ritual and the promise of the monstrous,” and their audience, spread out on mats and chairs in a semicircle around them, was about to find out what that meant. Trays of pork and beef skewers and samosas were passed around, and cups were topped off with pineapple-ginger juice. As the sky darkened and the birds quieted, the moon began to peek down through the canopy of leaves above us.

The three men opened the conversation by examining the rituals of life, those pesky traditions that we barely realize we’re upholding. We are all taught to stand in line, to follow the rules. We go to the store, the gas station, to church, to school, all without much thought. We are taught that’s the way to live and that civilizations persist off the strength of the social contract. But considering the fraught state of the world, is that the best we can do?

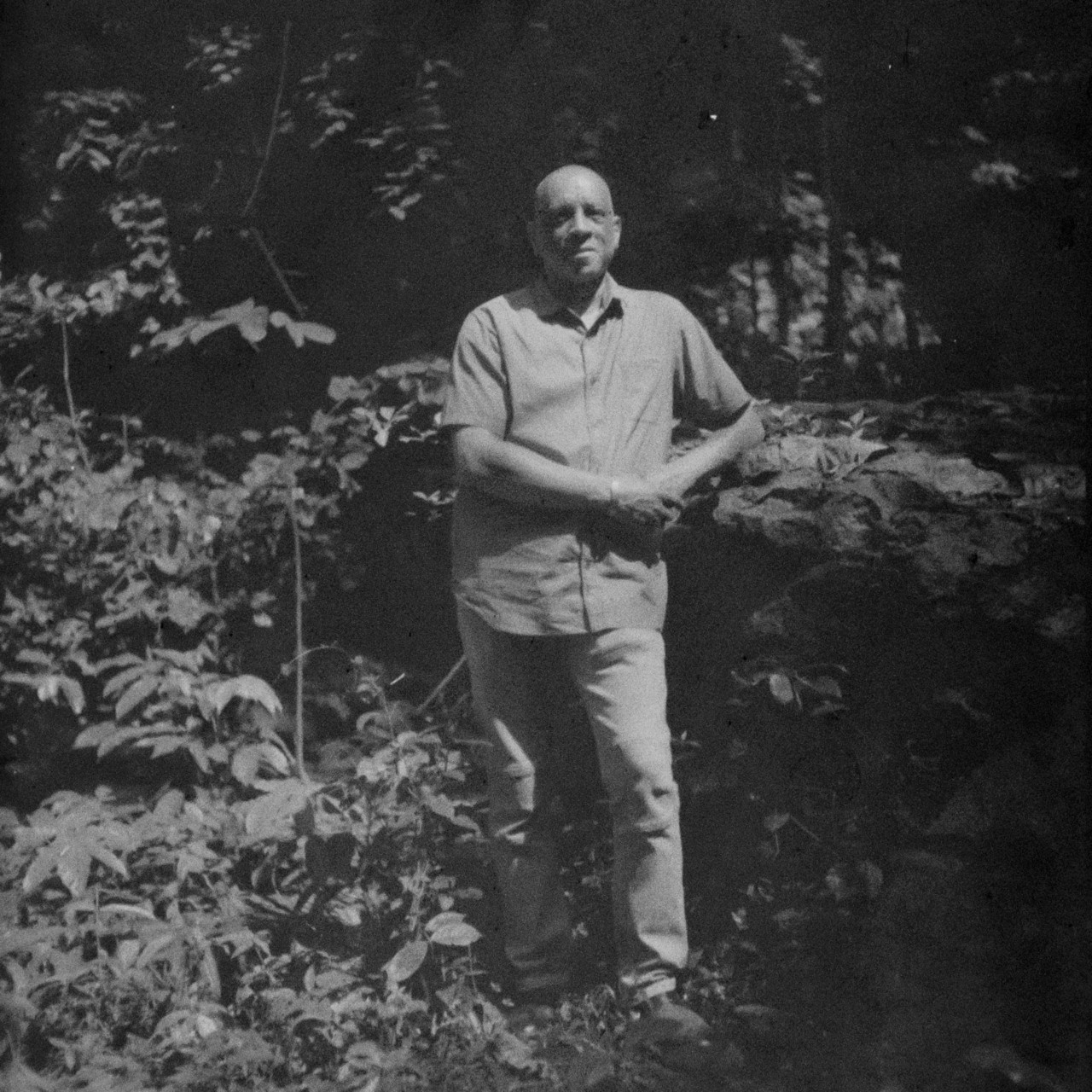

This is one of the elastic, rangy questions posed by Three Black Men, a symposium-cum-family-reunion, a series of gatherings through which Blackness—in all its multiplicity—is the lens through which we can reimagine our approaches. The previous seven days had been full of lectures, communion, and site visits (to places like Cape Coast Castle, one of the major holders of enslaved people before they were shipped to the West, or the W. E. B. Du Bois Memorial Centre for Pan African Culture, the former home-turned-museum of the radical thinker), leading up to this final event, in which we’d unspool everything we had gathered.

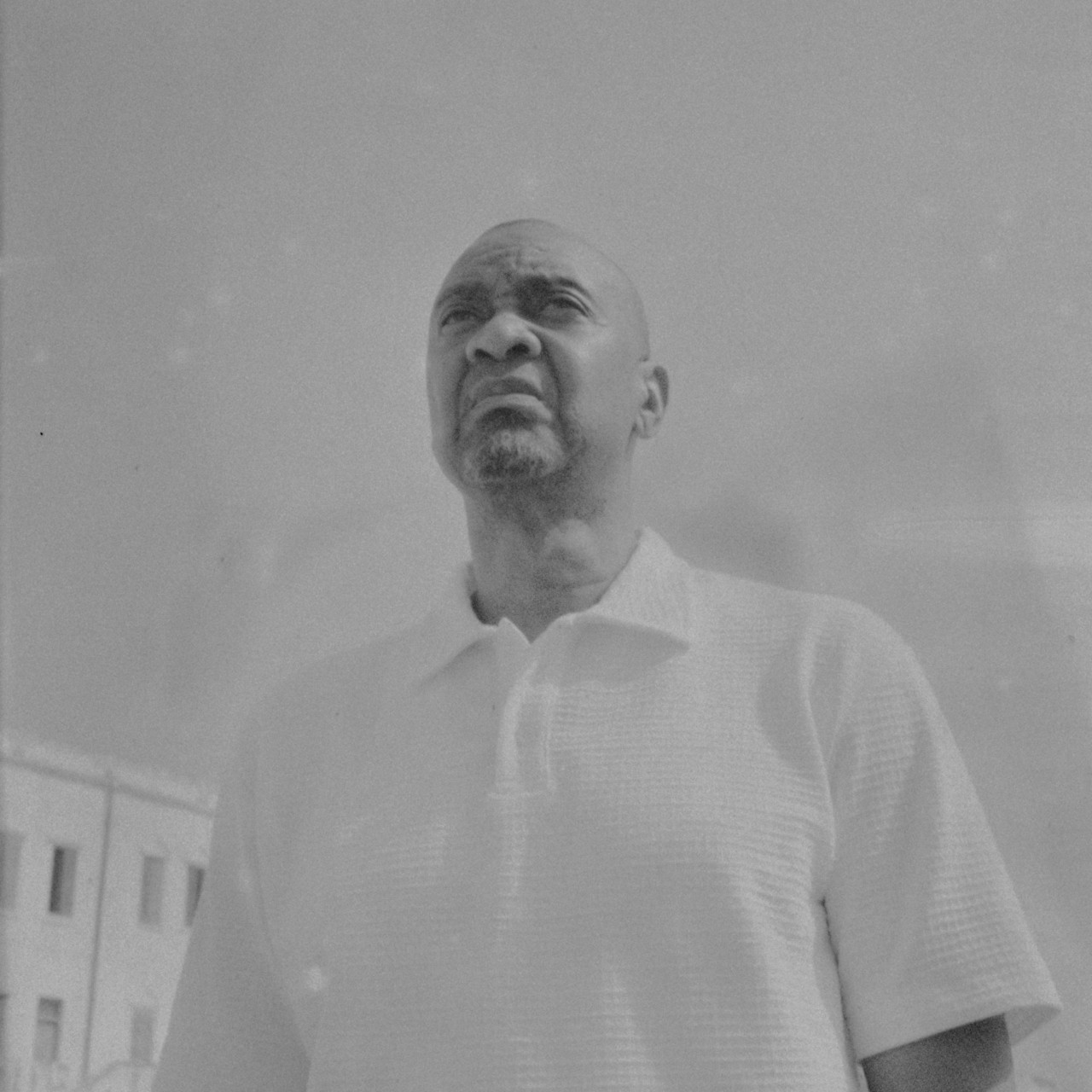

The three titular men are as tight as brothers, rarely out of each other’s reach over the trip. Akomolafe, who describes himself as a “speaker, author, fugitive neo-materialist com-post-activist public intellectual and Yoruba poet,” comes from Nigeria, a fact that he did not let street hawkers, eager to make a sale to unsuspecting tourists, forget. (“I am the same as you, brother,” I heard him say more than once.) Menakem, with a cheery and booming voice, hails from Minneapolis, where he is a practicing psychotherapist specializing in physical trauma and racism. Bishop lives in Los Angeles, where he’s a social healing activist and community leader, though he was born in Guyana. Whenever he spoke, the other two men stopped what they were doing to listen out of reverence and love.

The crowd murmured with appreciation. As an opening, Akomolafe urged us to think about our first introductions to limitation as proof of safety—for example, being given boundaries of play in our childhood (being told “don’t go beyond that tree,” or that building, or that line) and being made to fear the unknown void beyond it.

That childlike desire to push the boundaries, to go a step further than what was allowed, is the key to understanding the monstrous, which is simply a place of forbidden possibility, Akomolafe posited. “Multiple cultures around the world mark the edges with the idea of the monstrous,” he continued. “They say, Hey, if you go beyond this edge, and something happens to you, don’t blame me.” He encouraged us instead to explore those edges, the possibilities that have always been out of reach.

As they listened to the three men talk, half of the attendees were lying down on thatched mats and soft pillows. Rest and comfort were prioritized through the entire week of events, though Bishop reminded us of the dual nature of what happens when we close our eyes. “Sleep is a monstrous space,” said Bishop. “For a moment of time, it takes away everything we think we know and substitutes it with things we don’t know even about ourselves.”

The body has to be safe enough to imagine new possibilities; it needs the time to go there. That is the only way we can generate new pathways. “We are in a crisis of form,” said Akomolafe. “The forms we’ve taken up no longer serve.” What happens when the rituals no longer work? Where can we find new ways of thinking and seeing to combat the issues that plague our times? Beyond thinking outside the box: Can we tear the box into pieces and build a new structure out of it? This is what Black people have done for time immemorial, over eons, across cultures. Why stop now?

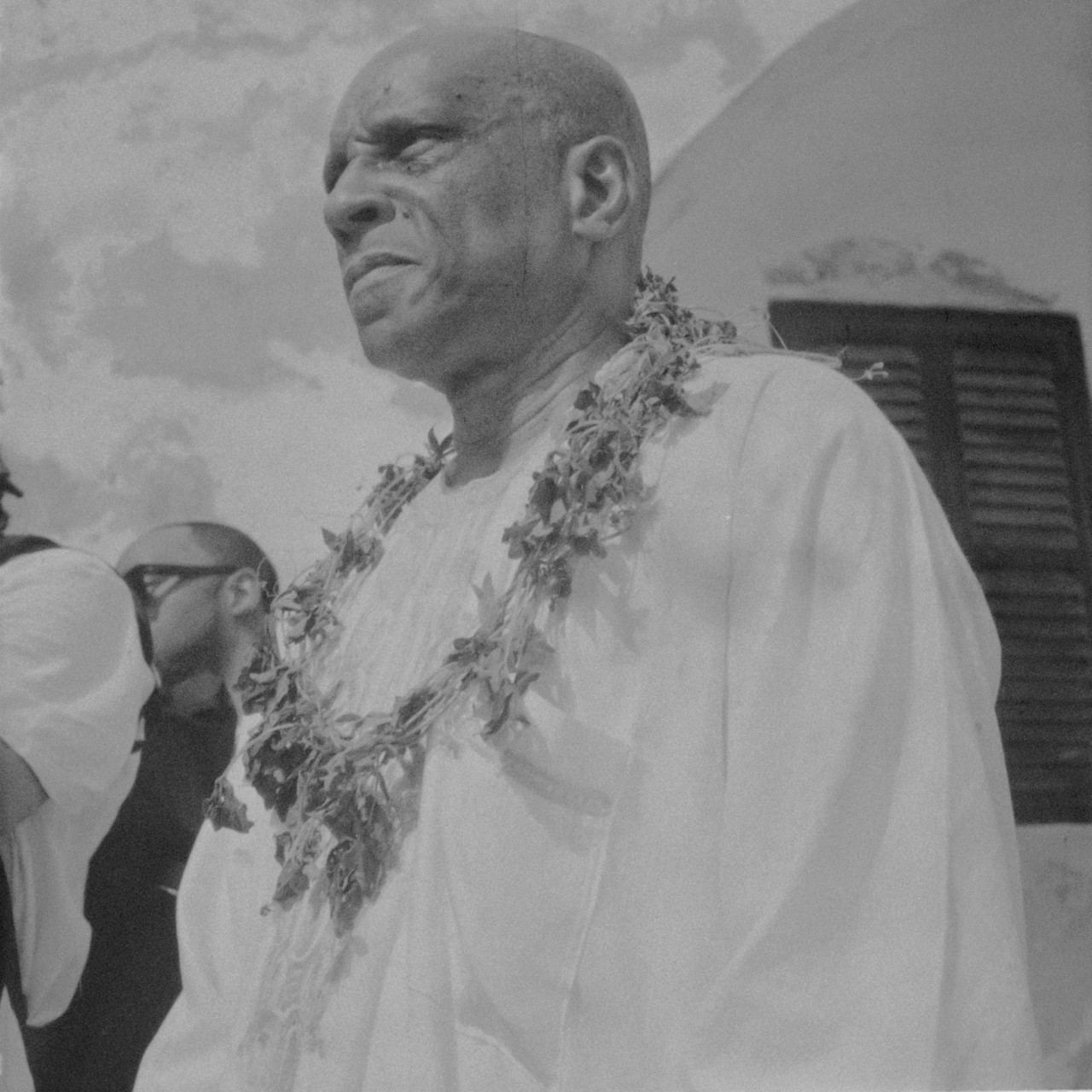

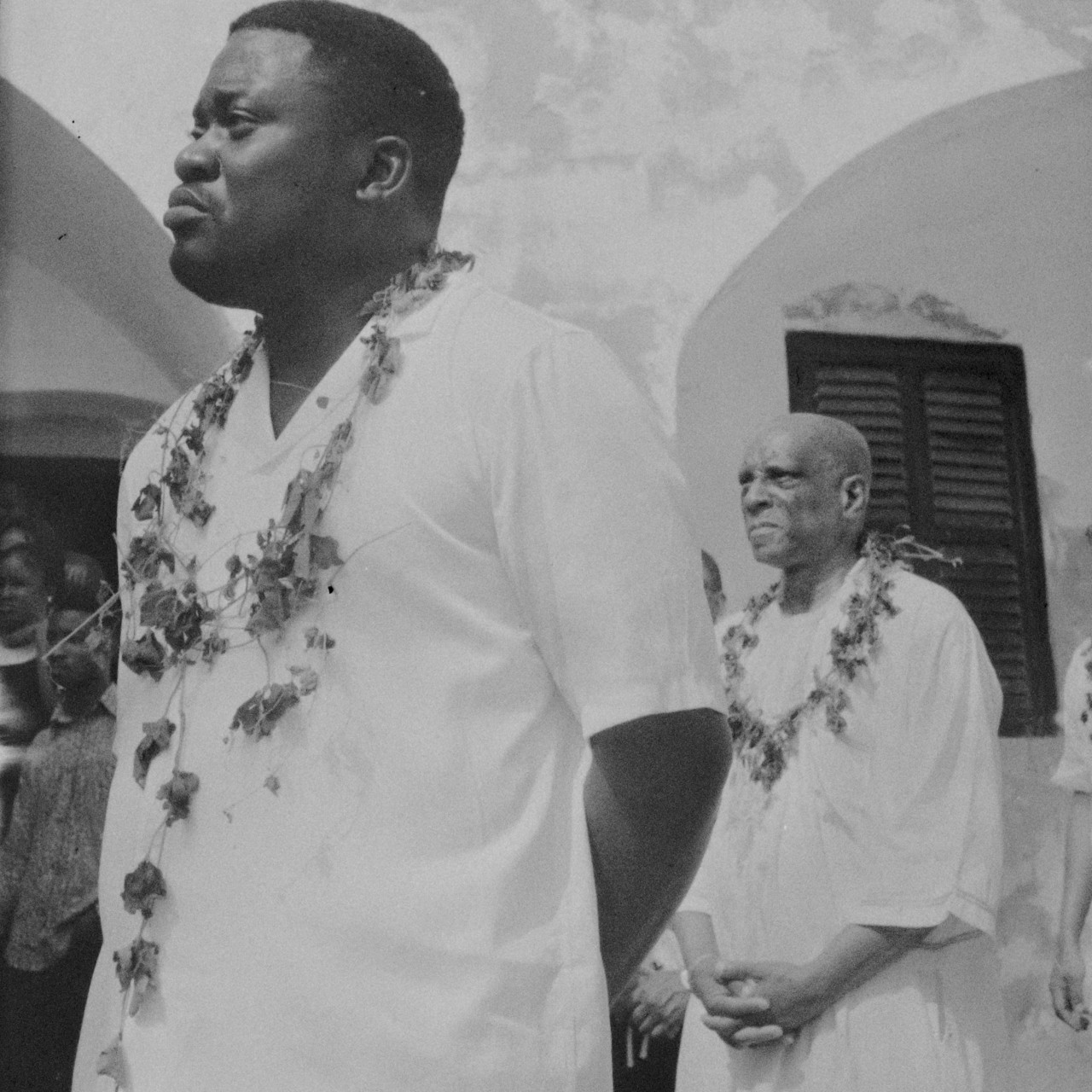

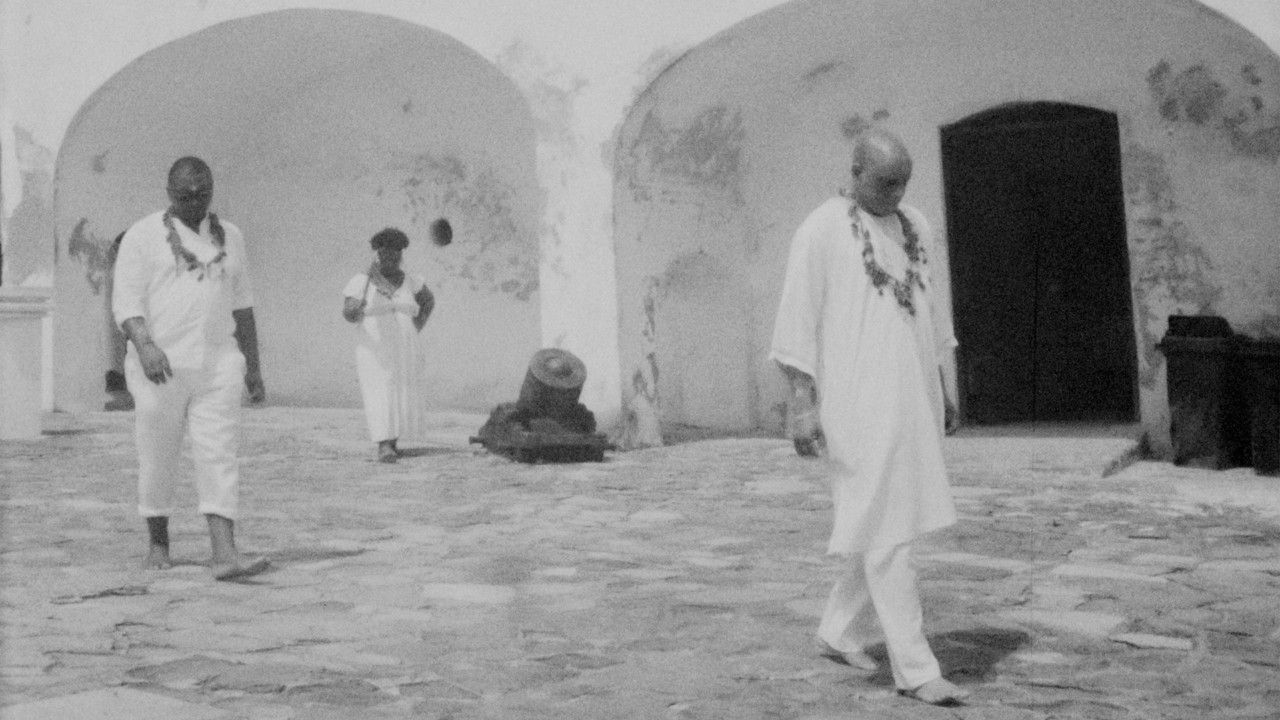

Earlier that week, the group of attendees visited the Afrikan Magick Temple, a Vodun temple in town. We were instructed to wear white, with some people pulling extra linens or jackets out of their bags for those of us who missed the aesthetic memo. When we gathered along the side of the road, we were blindingly bright, blending together, all pieces of the same vision. Before we walked into the shrine, we cleansed our hands and heads, then we were led into a space with penned goats and chickens. As we arrived, there was a drum circle full of young men from the countryside chanting, beating drums, and striking cowbells, encircling our group while the goats bleated and the chickens jogged around the perimeter.

The priest welcomed us back “home,” his face creased like a napkin. “All of you, welcome home.” This was the refrain of the trip, offered to visitors from the United States, Trinidad, Brazil, India, and Guyana, all of whom had come in pursuit of an answer. One woman, from Trinidad, said she wanted to stop feeling like a fake African. She collapsed and convulsed later, once we were inside the slave castles—the connection had finally caught up with her. The young men from Seattle had come with a few members of their extended family, wanting to forge a bond together. Their uncle had died, and their aunt wanted to spread his ashes, to return him back to where he belonged.

I’d been thinking about this trip as a return, although I’d never been to Ghana before. What unites a people: their joy or their pain? As soon as I approached the front desk to check into my hotel in Accra, the concierge asked me if I was Ghanaian. I was both flummoxed and pleased to be relieved, at least temporarily, of the burden of being American. (I imagine the question was answered as soon as I opened my mouth.) But I didn’t know what to say: I mean, I am as American as apple pie and student loan debt and school shootings, as American as four grandparents with the word “Negro” inked on their birth certificates and mastery of a single language.

But who am I to deny the story of my face? Its history precedes me. Somewhere among the roundness of my chin and my eyes, big as ramekins, this concierge had found something familiar. And besides, I do have Ghanian ancestry: I got an email with this news sometime in my early twenties, after the private company to which I stupidly entrusted my DNA finally came back with information more specific than “African hunter-gatherer.” My saliva showed that I had mostly Nigerian and Ghanian ancestry, a fact I flossed to my friend Lovia, who was born in Ghana but had grown up in New York. “Maybe we are cousins,” I teased her, drunk off the novelty of self-knowledge, of suddenly knowing more about my birth line than even my family’s most intrepid genealogists. Lovia put a hand on my shoulder. “You sound white,” she told me.

To the concierge I said, “Uhhhhhhh, no?” Maybe I meant to say: not any more.

But maybe someday, again. Understanding the trip as a return is to understand that time flows in every direction. Our presence had been here, carried in our ancestors, even if our bodies had not. “Coming back is a vocation of noticing that we never left in the first place,” Akomolafe said. “We’re finding that we’re larger than the story of captivity. We’re larger than the story of loss across oceans. We’re larger than the idea that we have been misplaced. And we’re noticing the gift of our multiplicity, of our largeness. So we are here to listen, to speak together, to eat together, to play together and to bolster reality.”

Beyond thinking outside the box: can we tear the box into pieces and build a new structure out of it?

In 2022, Victoria Santos introduced Akomolafe, Menakem, and Bishop. Santos had encountered each of them in her vocation as a racial justice and healing worker based in Seattle, and she figured they might enjoy each other’s company. Santos expected the men to have a single conversation, but the connection persisted. They dreamt up a project: coming together to find new ways to deal with old problems from a place of Black-led exploration, discovery, and transformation. Thus Three Black Men was born.

“Three is the trickster’s number in Yorubaland,” Akomolafe told me. “When two Black men gathered in the antebellum era, it was OK. When three Black men gathered—that’s violence, that’s a crowd.” The three refers not only to the project’s founders, but to the trinity of past, present, and future.

Originally planned as a single gathering, the project grew its own legs and launched first in Los Angeles, then in Salvador, Brazil, and ended in Accra, Ghana, honoring the Black and Indigenous creations of each city.

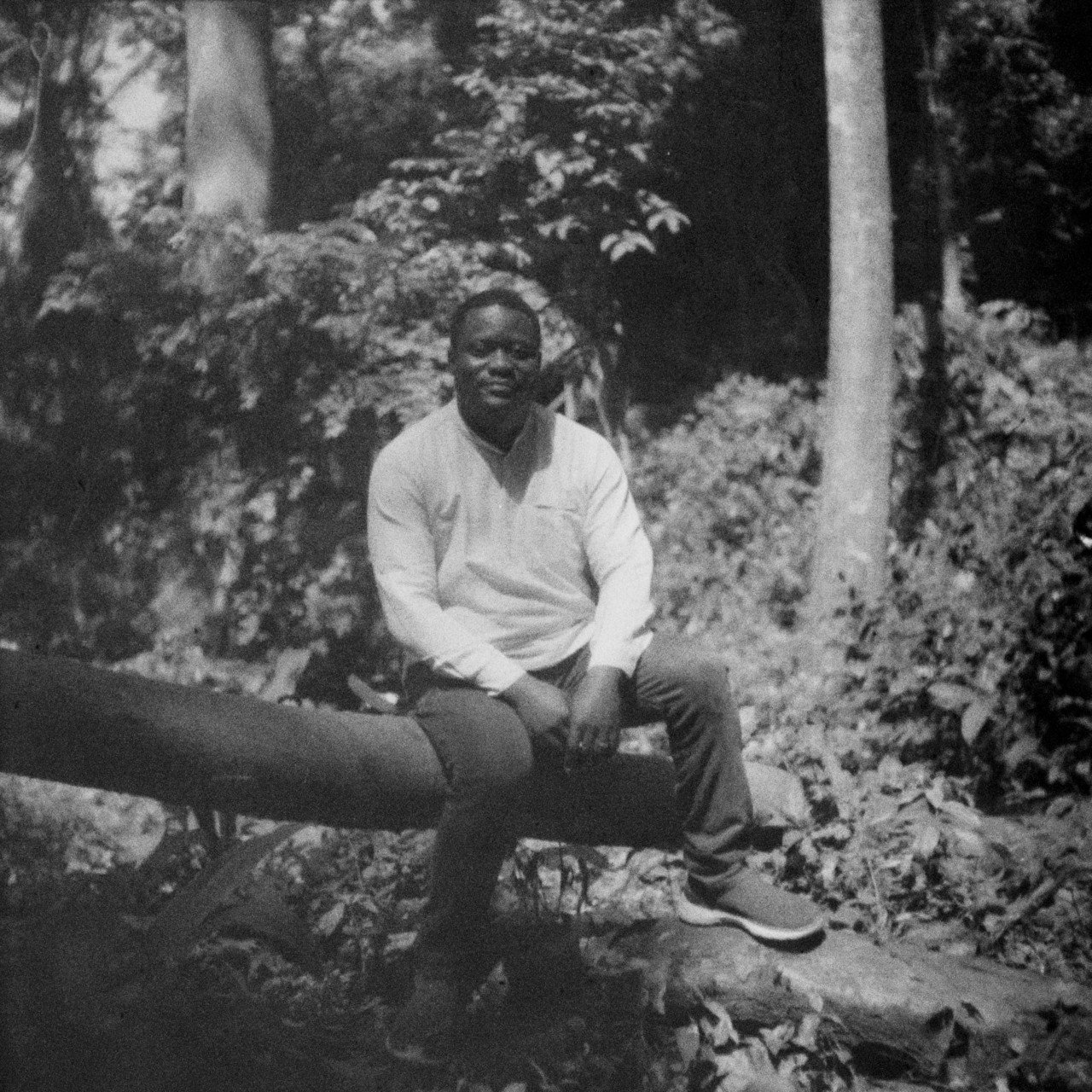

I arrived on a Tuesday evening, joining the group on the terrace of a restaurant called Afrikiko. The group had arrived the day before, spending that morning at the Asenema Waterfall, which was the topic of our dinner conversation. Everyone was kind and loose: walls knocked down, hearts wide open, already back-slapping and laughing with all of their teeth. Valerie, to my right, couldn’t stop talking about the power of the waterfall, how grounded she felt with her feet slipping through the mud. Someone started singing “This Little Light of Mine”—let it shine, for you and me, I’m gonna let it shine. They transcended the moment and traveled to another plane, together.

Massomeh Spahr, who ran logistics, told me that the intimacy was the point. This was the last leg of the symposium, and the group prioritized rest on this trip more than the others. “A large group would remove the sense of feeling,” she said. “Some people are coming to Ghana for the first time—you don’t want the experience to be too intense. Every day has softness and intimacy and slowing down.” Attendees came and went as they pleased, encouraged to recover from whatever was holding them down.

And indeed, the trip felt like family, like church. The soundtrack was set by the three men as they laughed, played, and even fought. (This is how their disagreements sounded: “My big brother, with deep love, knowing that we’re on this beautiful journey together, there’s an architecture, a design, a structure to your thought that has nourished me and continues to nourish me. But then there are some things that I have to disagree with.”)

The impact of the weekend, Saphr told me, should be that of a homecoming: the returning of our pieces that were stolen, raped, and torn apart—but returning with all our pieces, and feeling held in doing so. I am reminded of Black lesbian poet Pat Parker: “The day all the different parts of me can come along, we would have what I would call a revolution.” Whole, even if not intact.

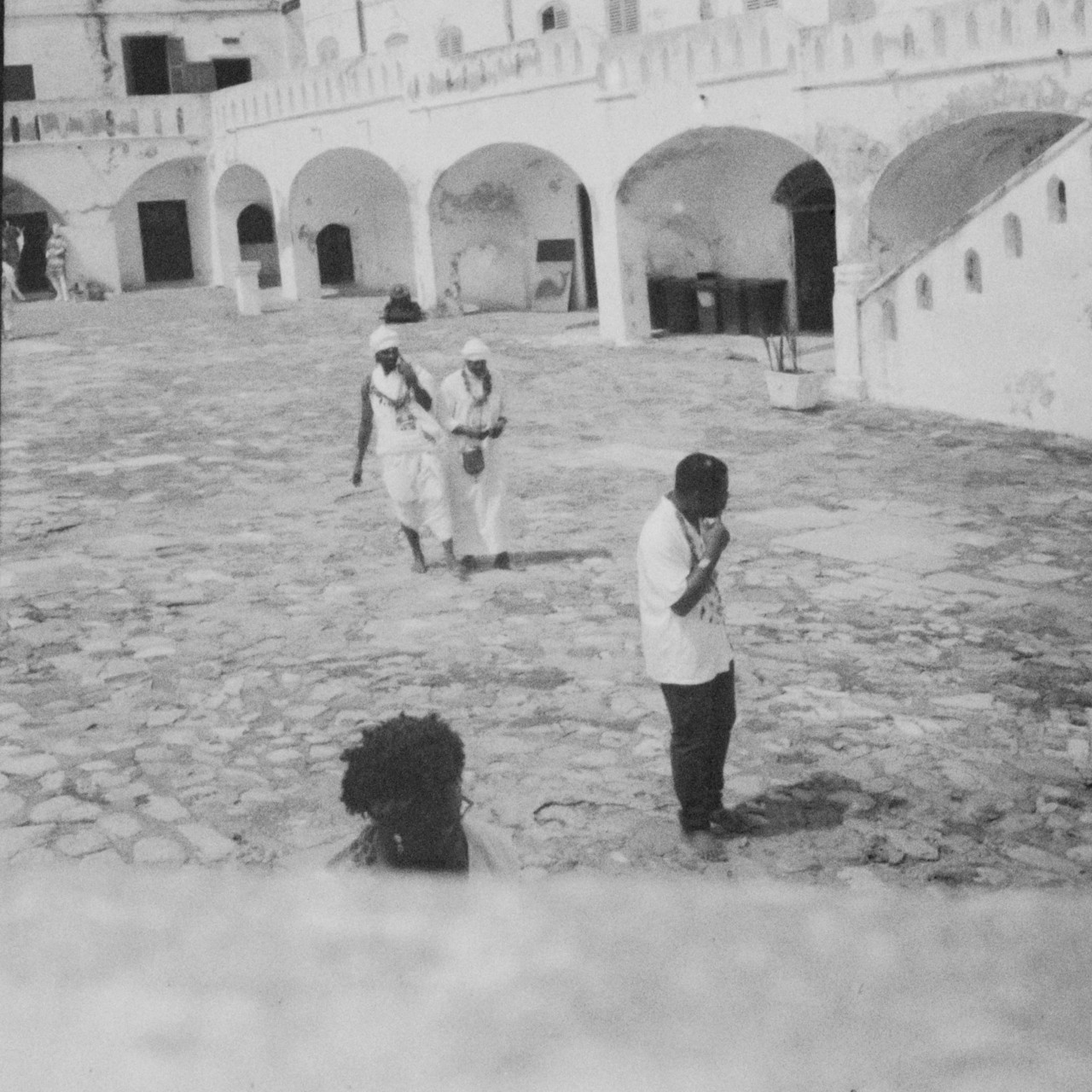

As we wandered the grounds of the Cape Coast Castle, as potent as they are cursed, the tour guide led us through the dungeons where captured Africans were held. Dungeon is perhaps too luxurious of a word: These were black holes, spaces where thousands of human beings saw their luck—and humanity—run out. The tour guide explained to us how many dozens of men were kept in captivity at a given time, how the holding cells had as little air and light as possible, how the layers of excrement and sick and blood and skin had fused together over the years into a coating so thick it cloaked the original brick floors, a history of pain. The women’s quarters had held so much blood over the years that the air in the space still smelled different.

Someone closed a door, and the air in the room tightened into a fist. Some of us couldn’t breathe. We held hands and wrists and limbs as a Vodun priest made an offering to our ancestors: two chickens and a bottle of rum. We held memory, we held pain, we held wonder and gratitude at all that had occurred between then and now, all the miracles and sweat that allowed us to be there. We stood beneath the window between the dungeons and the church erected atop of it, where parishioners could stare down into the tomb of the land and feel grateful that their god decided to keep them where they were. (The mulatto children, products of rape, were occasionally brought to the window and forced to consider their alternatives.)

Everyone wept in a different key: Some called out to God, voices full of righteous anger; others sobbed silently, trembling. One woman began foaming at the mouth, her body rejecting the poison in the air. Arms were everywhere: cradling, hugging, consoling. In the darkness of the caves I found myself comforted by arms I didn’t know, hands I couldn’t see, the chest of someone I couldn’t make out beyond the snot and tears. It was as if strings were pulling us together, knowing that the only solace was to come closer.

Outside the women’s dungeons, one man held the wall and cried, his forehead pressed into his forearm, rivers of pain flowing down his face. I’d never seen a man cry like a baby, like a boy, the sort of cry you have when you’re sure you’ve reached the nadir of your life. I’d never seen such a response, either: Men holding their brother. Tall, strapping men; short, round men; men who had been taught not to cry or to feel, rather to hide and bury. But here the rules did not apply.

What unites a people: their joy or their pain?

We collected ourselves and each other and ended our tour at the Door of No Return, retracing the path of our ancestors who fought to remain. The ground was pocked with thin half-moons or small depressions, the size of tablespoons, worn down over time from the shackles around their limbs that dragged on the floor. Air and light came through a window as big as a placemat. We closed our eyes and listened to the distant waves, the promise of a certain death.

On the other side of that door—marked, in 2019, as the Door of Return, to commemorate the 400 years since the first people were kidnapped from the continent and brought to what would become America, and to beckon people back—we caught our breath. Children selling sweaty bottles of water had been waiting outside for us, anticipating our need. Commerce stretched out as far as the eye could see; sellers followed the coastline. There were women selling beads and peanuts and perfumes, men hauling in the day’s catch.

After the castle, we gathered on the shore, to cleanse our feet, to anoint ourselves, to give thanks, to take space. We ate ravenously—chicken wings, salads, sweet rolls—and eventually piled back in the van, all types of sweaty and sad. None of us spoke; none of us were the same as we had been when we left that morning. On the ride back, I kept thinking of Gwendolyn Brooks: “we are each other’s / harvest: / we are each other’s / business: / we are each other’s / magnitude and bond.” We weren’t family, exactly, but we were kin.

This article first appeared in Atmos Volume 9: Kinship with the headline “Part I: Three Black Men.”

In Ghana, a Gathering for Black Joy, Pain, and Reconnection