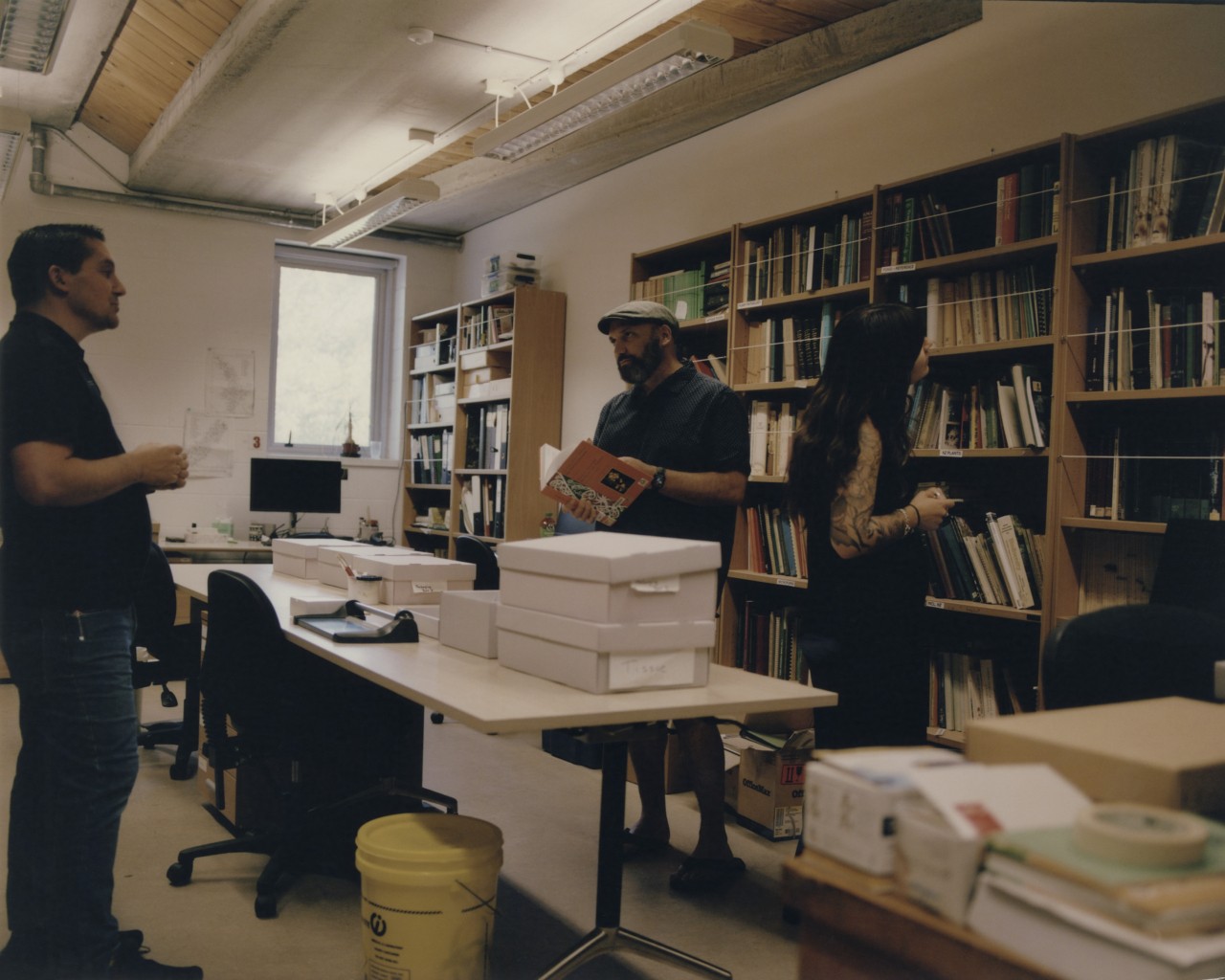

Left to right: Kaitiaki and phase one study participants Jody Toroa and Kay Robin

WORDS BY MOLLY HELFEND

photographs by apela bell

The hot summer sun beamed brightly onto Rangiwaho Marae (ancestral meeting grounds) in Gisborne. Beneath intricate carvings of ancestors in the wharenui (ancestral meeting house), a melodic karakia (ritual prayer or blessing) softly filled the sacred space. A small and focused group of Māori settled onto mattresses, their faces relaxed yet expectant as they prepared for the nohopuku—dosing sessions of psilocybin, a naturally occurring psychedelic compound found in certain species of mushrooms. They’ve been here before, but still, the anticipation for the psilocybin-assisted healing gently pulses through the marae. The connection between whakapapa (genealogy, lineage), matakite (special intuition), and the mushrooms is palpable.

These individuals are not here for recreation. They are here for Tū Wairua, a groundbreaking Māori-led psychedelic therapy trial designed to address substance addiction and mental health issues devastating Māori communities. A 2020 report from New Zealand’s Office of the Health and Disability Commissioner found that nearly 1 in 3 Māori experience mental illness or addiction in any given year—the highest of any ethnic group in the country. Tū Wairua aims to curb these epidemics and is currently in phase one clinical trials.

“After my psilocybin journey, my daily habit of drinking alcohol simply went away. Without conscious thought—just gone,” said study participant Jody Toroa, a trustee of Ngāti Rangiwaho (a Māori iwi, or tribe) and lead kaitiaki (guardian) on the project. “That’s the power of this taonga.”

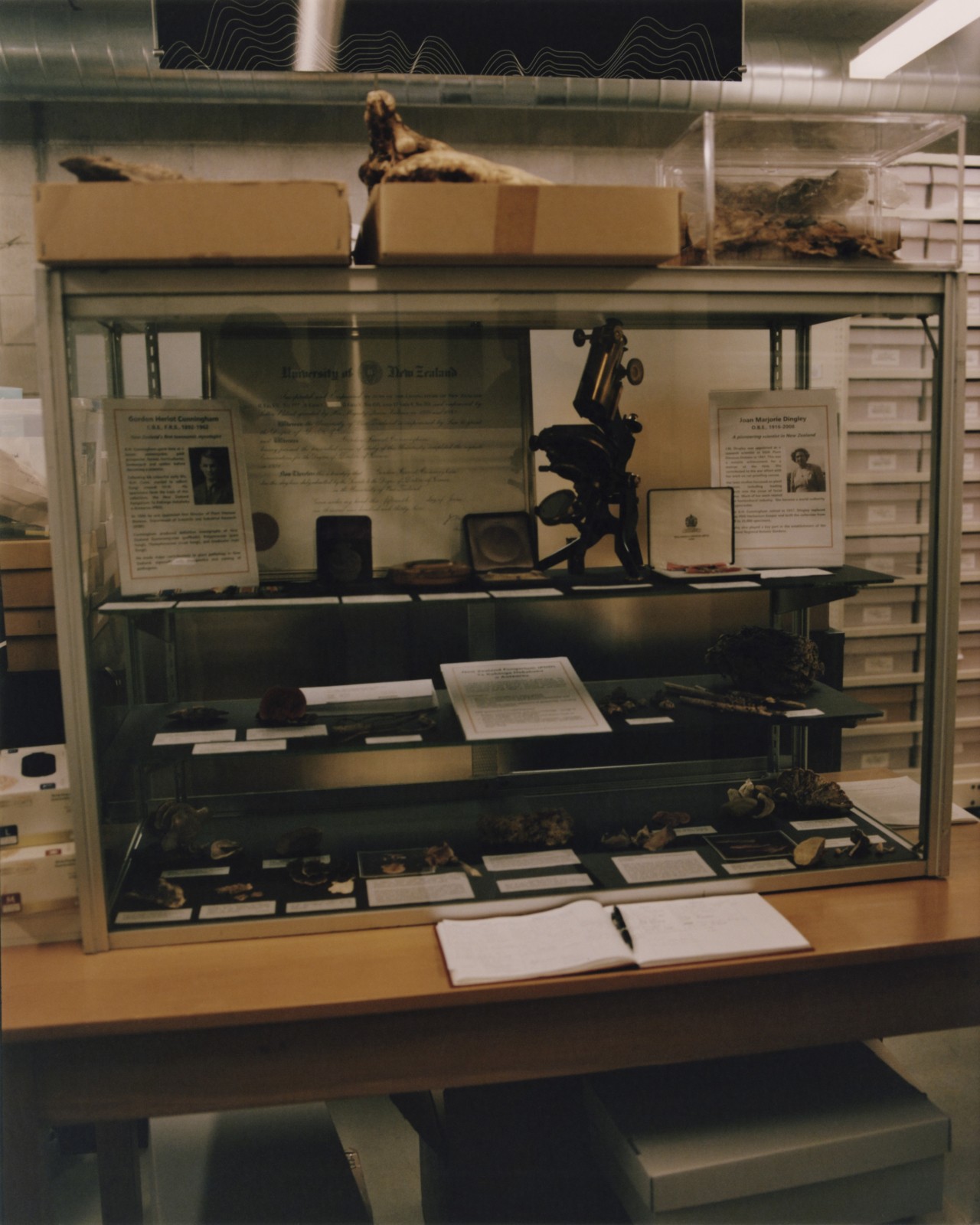

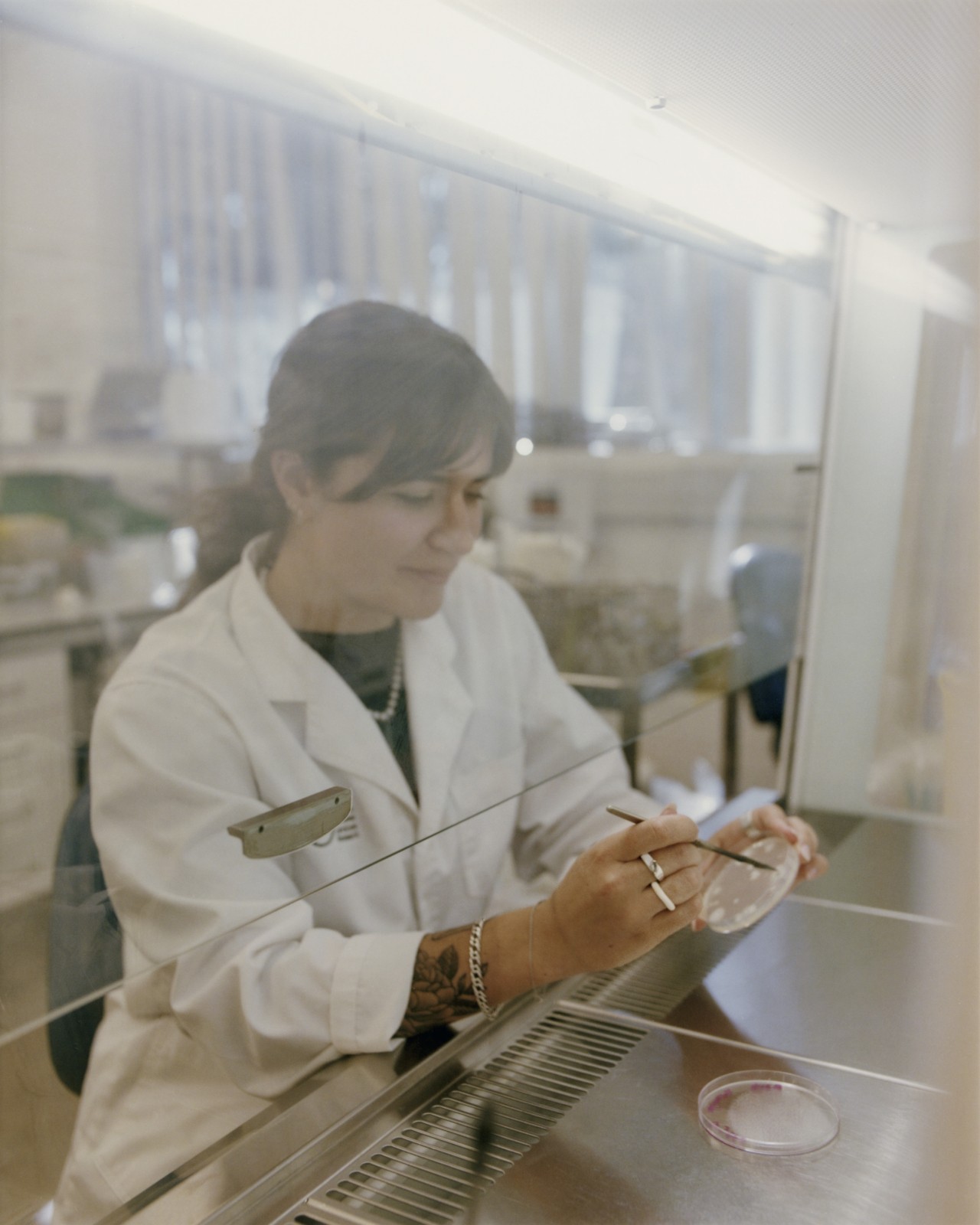

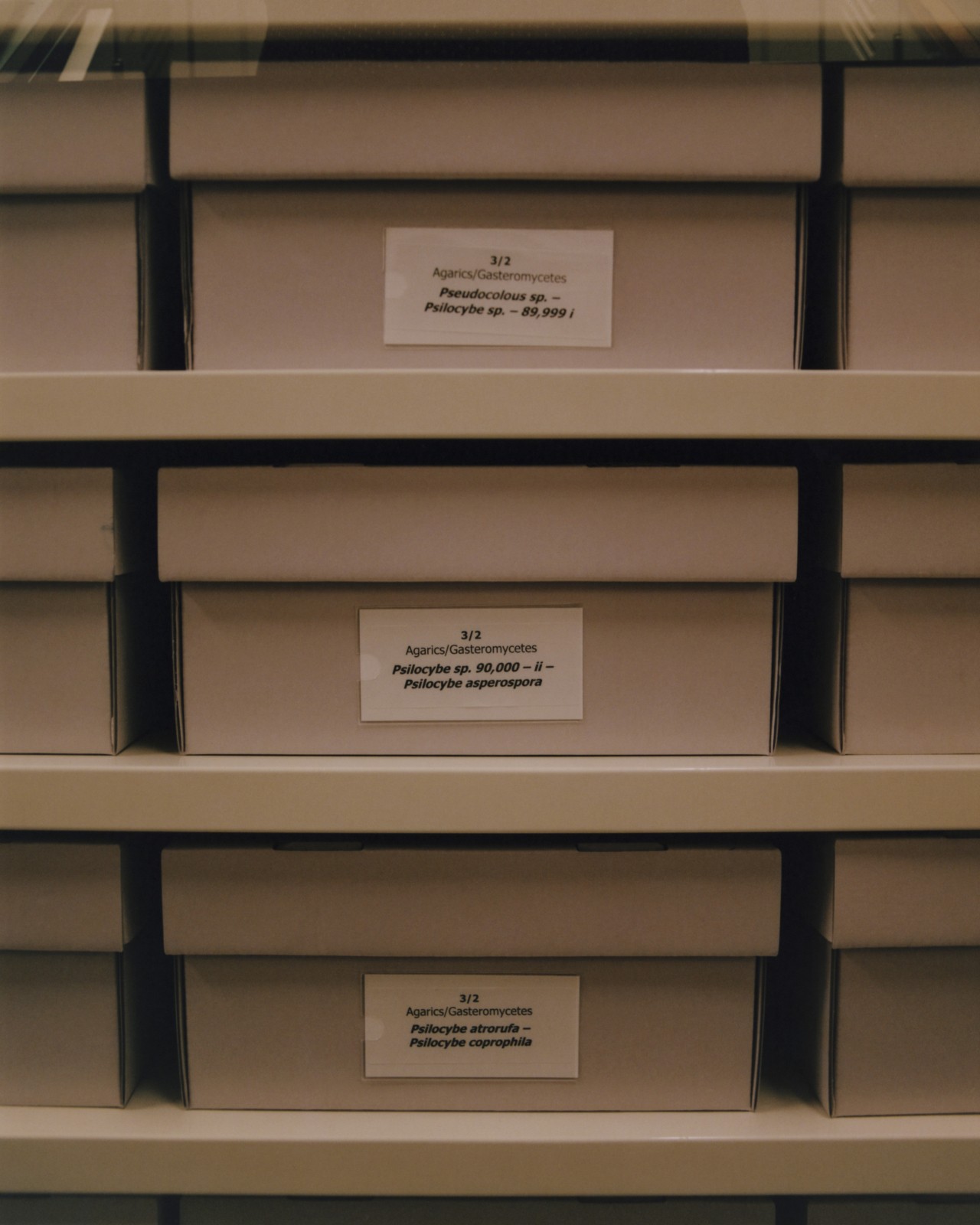

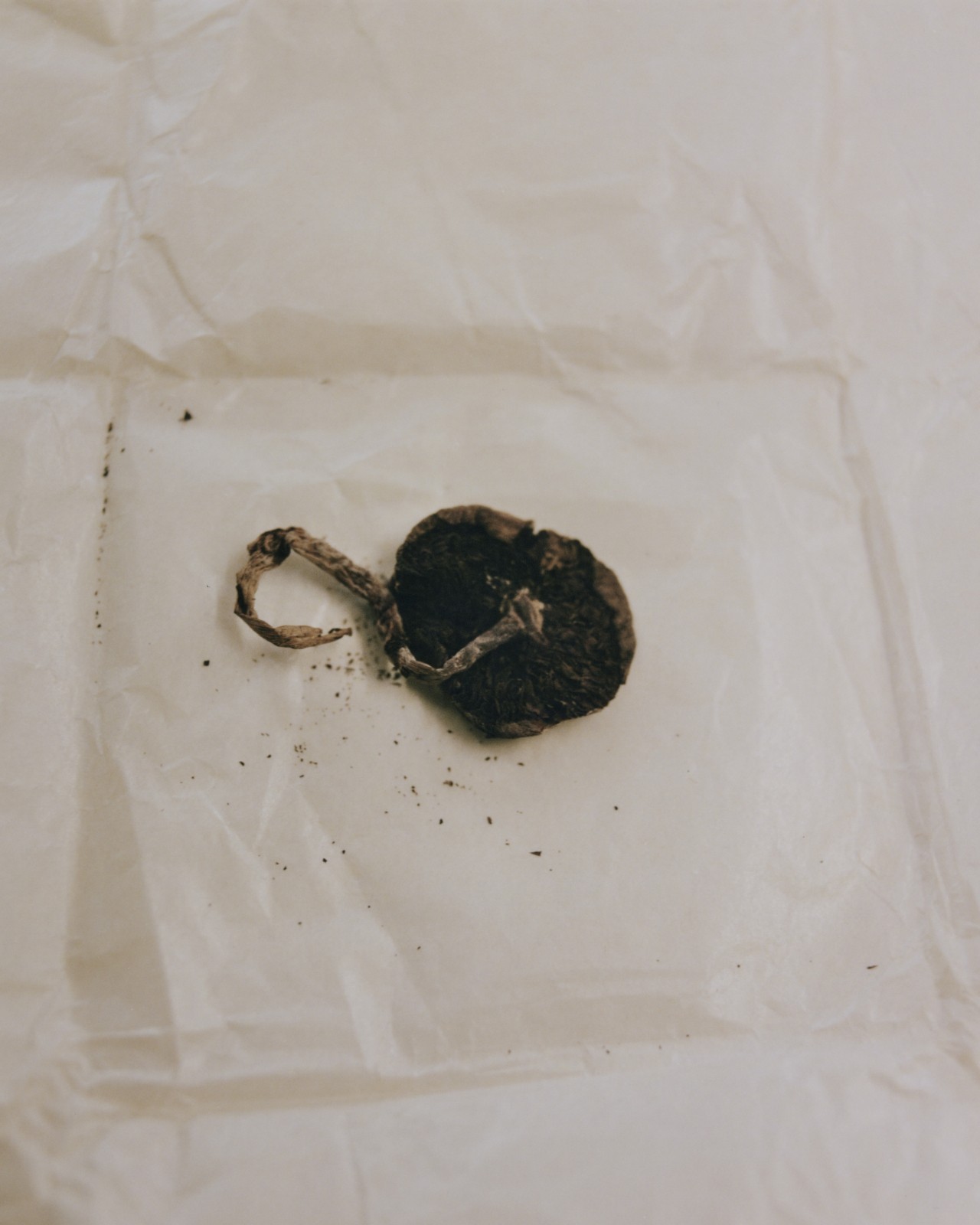

Currently, the trial uses imported psilocybin from Canada, but Tū Wairua secured a license to cultivate 10 varieties of native mushrooms domestically, including Whare Atua (the sacred name for Psilocybe weraroa). Colonization obscured traditional mushroom foraging over generations, but this initiative hopes to revitalize the practices. The vision is to heal mental health and mātauranga Māori (Māori knowledge systems).

“Colonization suppressed our knowledge,” said Toroa. “So, we have to learn new ways of changing the impact of colonialism.”

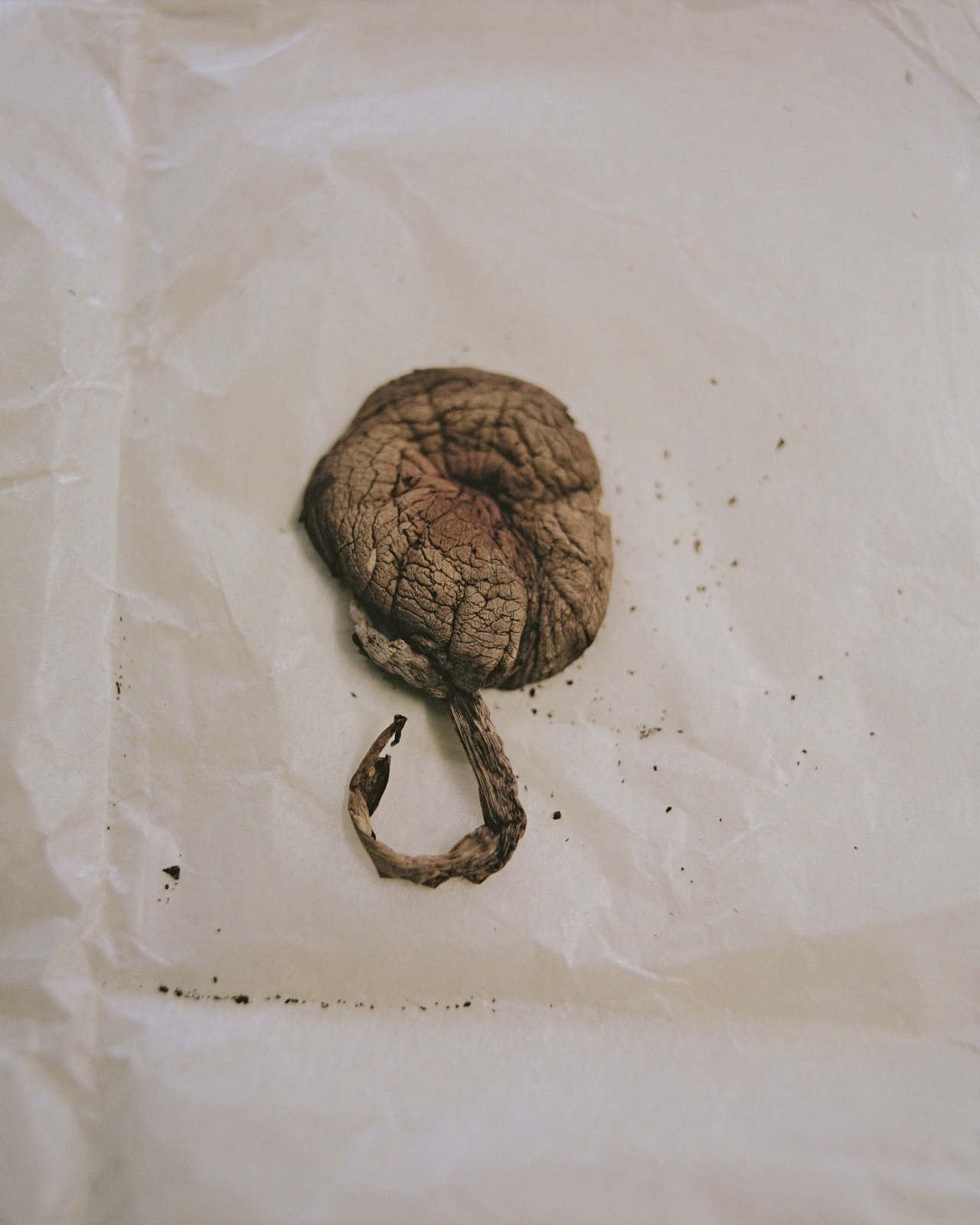

Whare Atua is an unassuming, small and bulbous white mushroom endemic to Aotearoa.

“It is gentle, quiet, shy,” explained Kay Robin, Ngāti Rangiwaho trustee, kaitiaki, and phase one study participant. “It guides you softly inward.” Like other phase one trial participants, Robin is healthy and has no addictions.

The mushroom’s unassuming nature masks its profound potential to shift consciousness. Māori recognize this mushroom as a sacred taonga (treasure), a natural psychoactive rongoā (traditional medicine) native to Aotearoa’s ngāhere (forest). However, colonization scrubbed it from collective memory and oral history. The Tohunga Suppression Act of 1907 outlawed Māori healing practices. When asked about traditional mushroom use now, elders—cautious about sharing sacred practices—often respond with silence.

“For Māori, there’s a whakapapa of not knowing,” said Will Tait-Jamieson, Tū Wairua project coordinator. “Reclaiming lost knowledge takes courage.”

“We are talking about healing intergenerational trauma,” added Robin. “This kaupapa (initiative) helps to release it.”

Tū Wairua first took root when Manu Caddie of the Ngāti Pūkenga and Ngāi Te Rangi iwi, or tribe, approached Rangiwaho Marae seeking a progressive marae open to explore Indigenous-led solutions for methamphetamine addiction. Caddie is the co-founder of Rua Bioscience, the first licensed company in New Zealand to cultivate native psilocybin mushrooms. Rangiwaho Marae was an ideal partner, having previously led local campaigns against meth use. “Affordable, safe, effective access to this medicine—that’s the ultimate dream here,” Caddie said.

In conversation, Caddie emphasized the importance of community-driven solutions. “Real change comes from the ground up… real change does not come from the government,” he said. “They’re either the ambulance at the bottom of the cliff or regulating for change that has already occurred in communities.”

“This kaupapa is about healing our people, healing our whenua (land), reclaiming our mātauranga Māori. Whare Atua will lead us exactly where we need to be.”

Indeed, the project is guided at every stage of research by a community of kaumātua (elders) and cultural experts. “Our old karakia is where you might find the answers,” Robin said.

As part of their ongoing phase one clinical trials, Tū Wairua is engaging healthy Māori kaiwhiwhi (participants) to establish safety protocols and cultural frameworks. The early results are encouraging: Toroa and other participants reported profound healing effects. Phase two, pending funding, will address the methamphetamine crisis plaguing Māori communities, especially along the East Coast. For future patients, Robin sees psilocybin not as a miracle cure but as “a window of opportunity” for those trapped in addiction to envision an alternative path forward.

“We intimately understand meth’s impact on our whānau (extended family or community),” she said. “Psilocybin can give genuine respite and clarity.”

That’s not to say the trial has proceeded without a hitch. Two centuries of colonization have tipped the delicate balance between cultural protocols, scientific rigor, and government regulation. To ensure scientific validity while honoring the tapu (sacred) nature of Whare Atua, Tū Wairua uses a hybrid methodology anchored by Māori wisdom and informed by Western scientific standards. But last month, these tenets clashed at a wānanga (ancestral knowledge exchange) when trial organizers discussed how to navigate strict protocols, substance approvals, and good manufacturing practice standards. Each bureaucratic hurdle presents time-intensive regulatory barriers and often feels culturally misaligned.

“It would be a shame if bureaucracy prevented people from exploring psychedelics to resolve seemingly intractable issues, issues we’ve failed time and time again to resolve, like methamphetamine addiction,” said project coordinator Jamieson.

Toroa has mixed feelings about balancing sacred practices with governmental regulation. She said the bureaucracy surrounding a taonga Māori feels “unjust” but appreciates that ”ethics and safety are paramount.”

Tū Wairua will have to successfully navigate that political morass if they’re to achieve their goal of reclaiming traditional Māori mushroom practices. Māori recognize all psilocybe-producing mushrooms as taonga, affirming their right to utilize them under Te Tiriti o Waitangi (Treaty of Waitangi): an 1840 agreement with the British Crown that grants Māori the right to possess and use nearly all their taonga. Caddie supports embedding these rights into law and sees next year’s elections as a pivotal opportunity for the project’s success.

“Indigenous peoples have never given up our right to utilize indigenous organisms,” Caddie said. “We’ve got a jurisprudence around treaty claims—radio spectrum, fisheries quotas—heaps of claims. So, there’s strong legal precedent. Psilocybin mushrooms can easily fall under that category.”

Robin envisions a future in which mushroom usage is openly accepted. “Eventually, whānau can reconnect with Whare Atua during Matariki (Māori New Year), as intended,” she said. According to inside sources, an underground network of tangata whenua (people of the land) who call themselves “shroomy Māori” already forages native varieties, quietly crafting sacred rituals and exploring traditional uses.

“Hopefully, it will become natural oranga (well-being) for our people,” Robin said. “Different fungi species for different purposes. Whare Atua for deeper spiritual and enlightenment journeys. Just like some of our more shroomy Māori are doing.”

For Toroa, the resurgence of a reverent, ritual-based relationship with Earth’s medicines offers more than just therapeutic benefit. It’s about righting the wrongs of generations past.

“This kaupapa is about healing our people, healing our whenua (land), reclaiming our mātauranga Māori,” she said. “Whare Atua will lead us exactly where we need to be.”

How Māori People Are Reclaiming Psychedelic Mushroom Medicine