Words by Ruth H. Burns

photographs by eric chakeen

Last month, I received an unexpected message. The email was simply a notification that a public forum was going to be held to discuss an upcoming repatriation of remains that was being conducted by my Tribe, the Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate. But, within that notification, there was a list of individuals given. The list named my paternal aunt as well as my paternal grandmother.

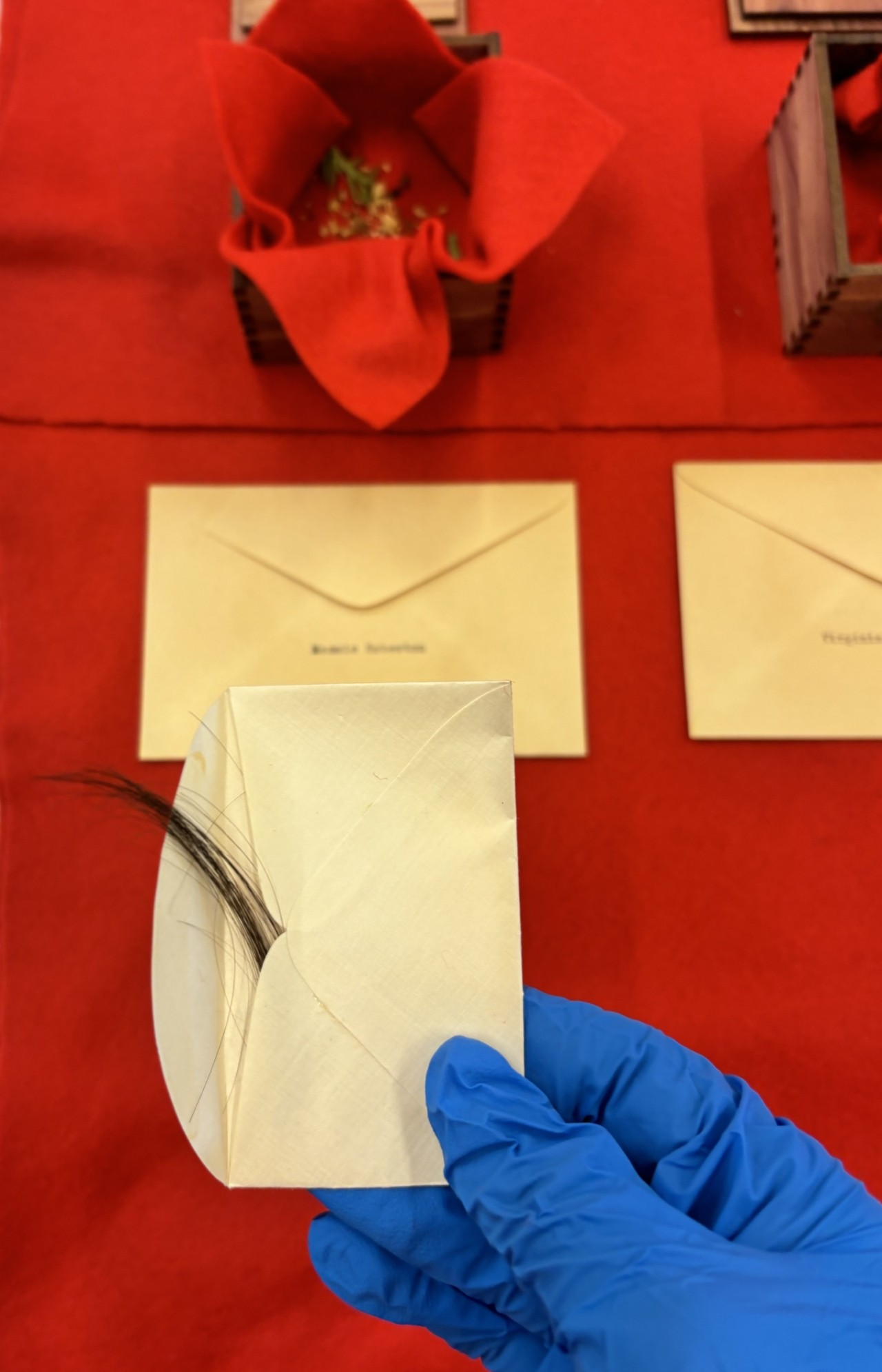

I’d just discovered that my Tribe was going to retrieve the hair clippings of my dead relatives from the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology at Harvard University. One never truly knows how one will react to the kind of painful, personal news that involves one’s heritage—but even I was surprised at how much of a gut punch reading their names on that list was.

As a Native woman, I’ve learned, by experience, that historical trauma is real. Maria Yellow Horse Brave Heart, a clinician and researcher, describes historical trauma as the “cumulative emotional and psychological wounding over the lifespan and across generations, emanating from massive group trauma experience.” For Natives, historical trauma is rooted in the attempted genocide, violent colonization, and forced assimilation our people endured and continue to face to this day. The Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate belongs to the Santee division, or Frontier Guardians, of the Oceti Sakowin (Seven Council Fires), commonly called the Great Sioux Nation. We are a woodlands people. We speak the Dakota dialect of the Siouan language.

Within our history you will find a War in which our Minnesota homelands were stolen, and 38 of our ancestors were hanged in the largest mass execution in U.S. history. You will also find sordid tales of bloody massacres, exile, forced relocation, starvation, and bounties that were put on our scalps. Even as recent as the last century, our children were sent to boarding schools where they were stripped of their language and culture, neglected, and horrifically abused. Some never came home.

And while we refer to this ghastly phenomenon as “historical” trauma, we are not far removed from these tragic events. My direct ancestor Chief Wabasha was a leader during the aforementioned Dakota War. My great-great-grandfather, who acted as a scout and translator for the Dakota, was tried but acquitted. My father and his siblings were all boarding school survivors, with the exception of one, who died there.

When Native children were sent to boarding school, their hair was always cut to sever their cultural connection to their people.

My reaction was visceral. Even though I have spent half of my life doing the work of healing from the intergenerational trauma I had inherited, I had to take a step back in order to mentally and emotionally prepare myself before re-examining the announcement.

Long forgotten memories flooded my brain. My grandmother had been our next door neighbor when I was a little girl. My cousin lived with her, and together we spent hot summer days running through a sprinkler in her yard. She crocheted colorful blankets and drove a yellow VW bug. Even though she was an elder, you could still tell that she was once very beautiful. I know what Winston cigarettes smell like because of her. My mind’s eye shot images of nights spent at my aunt’s immaculately kept house in Poplar, Montana, and of the quiet dignity and inborn authority she commanded, even in the presence of my father, who had been a tech sergeant in the Air Force and was quite domineering himself.

The Peabody Museum, in accordance with the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA), had completed an inventory of the human remains in their possession and notified my Tribe that a portion of those remains were taken from us.

The Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA), enacted in 1990, provides for the protection and return of Native American human remains, funerary objects, sacred objects, and objects of cultural patrimony to the lineal descendants, Tribes, and Native Hawaiians whose lands they were taken from and who they rightfully belong to.

To understand the gravity of what was taken, you must know that hair is sacred to my people. Our hair is imbued with spiritual power, and cutting one’s hair was not taken lightly. Traditionally, one’s hair was only cut for spiritual reasons like the death of a loved one. Even the cutting of one’s hair for this reason involved ritual and ceremony.

These colonizers had taken the hair of my aunt and grandmother without their consent. According to the notice provided by the Peabody, Orrin C. Gray took the hair clippings between 1930 and 1933. Gray then sent the hair clippings to George Woodbury, who donated the hair clippings to the Museum in 1935. My aunt would have been between eight and 11 years old when her hair was cut, and my grandma would have been between 11 and 14 years of age. They were just children.

The collection likely took place in connection with boarding school. When Native children were sent to boarding school, their hair was always cut to sever their cultural connection to their people. The goal of boarding schools was to assimilate Native children and make them over in the image of the colonizer to become part of a new servant labor class. To “[k]ill the Indian and save the man,” said Richard Henry Pratt, the superintendent of the Carlisle Indian Industrial School, one of the most well-known boarding schools where Native children were sent.

My Tribe had put in a joint claim with the Spirit Lake Nation, our sister Tribe, to retrieve the hair clippings, as well as four ancestral remains. The Peabody had those, too.

This isn’t the first time my Tribe has repatriated the remains of our ancestors thanks to NAGPRA. Last year, the Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate and Spirit Lake Nation entered into a pact to bring home the bodies of two of our boys who had died at the aforesaid Carlisle Indian Industrial School, where they had been buried under military-issued headstones peppered with spelling errors for over 140 years. Nearly 3% of all Native children who went to Carlisle, or 233 students (that we know of), died there; 180 of those that died from 1879 to 1918 were buried next to the school. Both boys arrived at Carlisle in 1879. Amos La Fromboise died just three weeks after arrival. Edward Upright, who was the son of Chief Waanatan, held on for a few years before dying while a student there.

The process of retrieving the remains of the boys was long and arduous. More than a year passed between approval of disinterment to scheduled disinterment. Officers who work in the Tribe’s Historic Preservation Office were charged with finding the closest living relatives of the two boys in order to satisfy requirements. They were elders from the Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate and the Spirit Lake Nation. Tribes were also apprehensive about what they would uncover in the process of disinterment. Other Native children have been disinterred from Carlisle cemetery. In some cases, bodies were missing, or an assemblage of body parts from different children were found in the same grave. Thankfully, the two boys were found whole and were able to come home, lovingly wrapped in buffalo robes, and buried in their ancestral lands, close to their relatives, honoring the lives they once led here as free Sisseton Wahpeton children.

This is the sacred hoop of life being mended. This is a mighty wrong, being set right.

Currently, the Kit Fox and Pte Canke Win societies of the Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate are raising money to repatriate the hair clippings and remains being held by the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology at Harvard University. Kit Fox, an ancient warrior society comprised of Tribal veterans, departed for Cambridge, Massachusetts on March 21, and returned on March 24 or 25, 2024. Once my aunt and grandmother’s hair is back in Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate ancestral lands, a ceremony will be performed and my family will be notified.

Please know that I am far from my aunt’s and grandmother’s only descendant. My aunt passed away in 2017, and we lost my grandmother in 2007. They lived long lives, had children and grandchildren, and come from large extended families. The oldest son of my aunt is getting together with his siblings to decide how best to proceed once her hair clippings are returned. Another granddaughter of my grandmother has stepped forward to claim her hair. We will likely have a family ceremony and then bury her hair clippings with her body.

My father died of COVID-19 in 2020. Since receiving news about the hair clippings, I have felt his presence. As his child, I think it’s important to represent his interests. He was especially close to my aunt, who was his oldest sister. He had such deep, profound respect for her. After she died, his demeanor changed. He became the last remaining member of his birth family. Indeed, he was grieving for her. But more than that, something in him gave up a little. He wanted to join her on the other side, and said as much. He would want my aunt’s and grandmother’s hair clippings to be returned to our family.

This is the sacred hoop of life being mended. This is a mighty wrong, being set right.

Repatriation is crucial for healing to take place, not just for Native peoples, but the descendants of the colonizers and the institutions they now inhabit. Repatriation is an admission of a wrongful taking, and shows a willingness to return what is sacred. While the harm cannot be undone, it can be acknowledged and reconciled. In this case, the law is just for my People.

Taking Back Our Ancestors