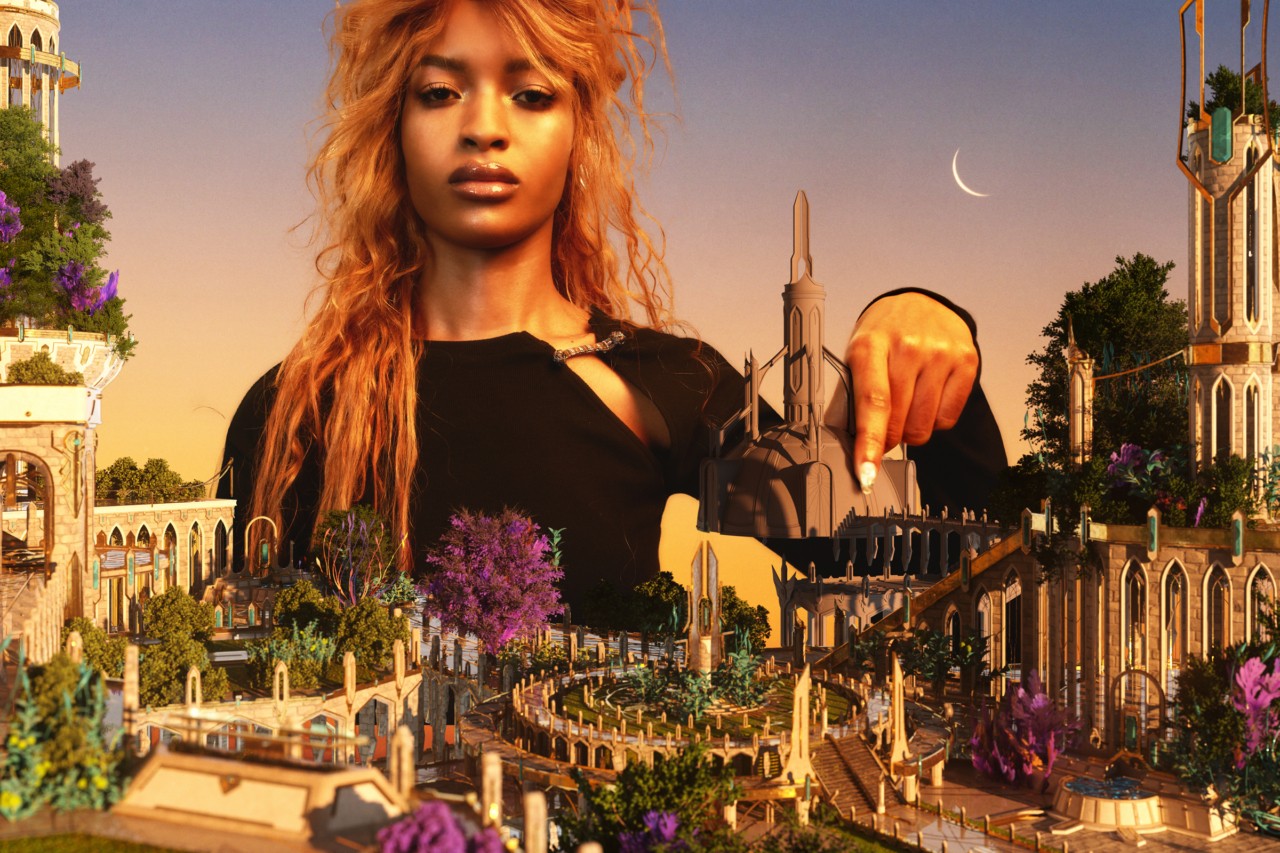

For Atmos, Bryan Huynh photographed an eco-heroine in six original computer-generated worlds. As video games often do, these imaginative, fantastical realms shimmer with the boundless possibilities of a more sustainable future.

WORDS BY LEWIS GORDON

photographs by Bryan Huynh

A bird flutters across the screen, its silvery feathers catching the eye before nestling snugly in the gnarled branch of a pine tree. In video games, birds usually disappear the moment you look away, ephemeral set-dressing in oftentimes teeming virtual worlds, but not this one, who hops down onto the ground and begins to peck around for food. I pull out my in-game smartphone and line up the camera, hitting “snap” just as it’s about to take flight again. The phone whirs, scanning the bird, telling me that it’s a Eurasian sparrowhawk, a rare sight on this tiny Spanish archipelago whose avian population consists mostly of the humble pigeon.

Something may happen to you if you play Alba: A Wildlife Adventure (2020), just as it happened to me. Now, when I look out at my overgrown garden in Glasgow, or walk through forests just outside the city, I’m alert for birds. I see a flash of blueish black and think “house martin”; I spot arrowed tail feathers and say “swallow.” It’s basic stuff, sure, but these are creatures I’d either forgotten or didn’t know in the first place. My own state of forgetting, and oftentimes ignorance, is reflected elsewhere. Children’s dictionaries, once flush with the words of nature like “kingfisher” and “otter,” have become increasingly bereft of wildlife, just like our landscapes. Some blame video games for rising apathy towards the outside world—“too many kids play Fortnite,” grumble the adults—but, in a meaningful way, Alba: A Wildlife Adventure has the opposite effect: It brings neglected nature back into focus.

Video games, like every other cultural medium, are wrestling with what it means to live through cataclysmic environmental and climate change. There has been a palpable shift in virtual representations of landscapes in recent years, from the geoengineered planetary playground of Anthem (2019) to the weather-beaten warzones of Battlefield 2042 (2021). There is a burgeoning subgenre called eco-horror, including Death Stranding (2019) whose pristine version of the United States is intermittently ruptured by Lovecraftian monsters made from a fictional, oil-like substance called chiralium. But games, rather than darkening our imagination, succumbing to a bleak kind of fatalism, or repackaging disaster as entertainment, might also plot routes beyond climate disaster. They could lay seeds for new action and maybe even new concepts of human-nature relationality.

Games, rather than darkening our imagination, succumbing to a bleak kind of fatalism, or repackaging disaster as entertainment, might also plot routes beyond climate disaster.

Alba: A Wildlife Adventure is a modest yet beautifully executed intervention, a game that occupies a similar tonal space to the growing body of children’s books that engage with environmentalism and the climate crisis. Speaking from his apartment in Valencia, creative director David Fernández Huerta said he wanted to make a game that he could play with his then-four-year-old son. He grew up in the city on Spain’s eastern coast during the 1980s and ‘90s, but his grandparents lived nearby in Náquera, a dry mountainous region populated by pine trees and all manner of wildlife. Aided by his grandparents’ nature books, the youngster photographed the locality’s animals. Alba is partly based on those experiences.

There’s more residing in Alba’s craggy landscape than animals and flora alone. Fernández Huerta, who made the game during a 10-year stay in the U.K., describes it as part of a process of “reclaiming” the nature of his Iberian home—reckoning with the emotional pull of the landscape and the sense of belonging it imbued within him. Alba is also an unambiguously didactic work, and yet, perhaps because of its cute aesthetic and breezy, engaging tone, it never feels preachy. Its villain is a middle-aged mayor who, backed by a pernicious property developer, seeks to build a luxury hotel where a wildlife reserve sits. You must gather signatures for a petition to halt this expansion. Alba, then, is also a primer in political activism.

In September 2014, over 300,000 people took to the streets of New York for the People’s Climate March. With an eye on the United Nations’ Climate Summit happening in the city a few days later, the writer and co-organizer Bill McKibben described it as a “loud movement—one that gives our ‘leaders’ permission to actually lead, and then scares them into doing so.”

Sam Barratt, then working for global advocacy group Avaaz, was another of the demonstration’s organizers. He now works for the United Nations, chief of the environmental education and youth unit, through which he cofounded Playing for the Planet, an initiative that aims to inspire environmental change in and through the video game industry. Barratt described video games as a “unique and precious medium,” one that, because it is so social and goal-oriented, can generate “civic will” more than movies, music, or even social media platforms like TikTok.

Barratt sees video games as a logical forum for climate discourse because they can engage large crowds in new kinds of conversations. Alongside the ambitious push for industry-wide decarbonization, Playing for the Planet has hosted four “green game jams,” remote workshops in which game companies like Ubisoft and Tencent have devised sustainable themes and gameplay mechanics. It has published a report on the theories and methods of devising such “green content.” The thrust of these efforts ultimately rests on the idea that the medium might help foster a new generation of conscientious, ecologically-minded citizens. In short, that video games can function like Aesop’s fables of Ancient Greece—as tools of moral instruction.

Alongside these top-down initiatives, players themselves have proven more than capable of playing “sustainably” and “eco-critically” without such prompts, particularly within open-world games. The genre is well-suited to this type of play, often serving up natural landscapes that facilitate extensive player agency.

One player, who goes by u/bigbear1992 on Reddit, tasked themselves with playing Horizon Zero Dawn (2017) as a vegan, foregoing the use of animal products and riding of animals (even robotic ones). Michelle Westerlaken, a researcher at the University of Cambridge, did the same in The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild (2017). Westerlaken discovered that she was able to adhere to the rules of veganism more strictly than in the actual world. “Rather than a small-scale simulation of real life,” she wrote, “the gameplay offered me an extra imaginary space… A space where a vegan utopia or a firm political response towards certain vegan ideologies can be imagined, materialized, strategized, and played out.” A discussion about a vegan run of Breath of the Wild took place on Reddit, some chatting constructively while others spouted belligerent abuse. Gaming is so often thought of as a lonesome, siloed experience, but here was Barratt’s contention in process: A “new kind of conversation” was being created.

As Nicholas Lund, an avid birder, video game player, and writer, said, video games allow you to “try on something you wouldn’t otherwise be.” That might be playing with the ethics of animal consumption, foregoing violence, or perhaps even engaging in it. For Lund, though, the open-world Western, Red Dead Redemption 2, offered a space to indulge his real-life passion. The National Audubon Society employee swapped real-life virtual binoculars for virtual ones, whisking gruff protagonist Arthur Morgan away from high noon duels and cattle rustling for the altogether more tranquil pastime of birdwatching. Red Dead Redemption 2 was the perfect game to do so, brimming with so much wildlife that researchers have found it improves knowledge of natural phenomena. Already au fait with Red Dead Redemption 2’s nonhuman inhabitants, he found himself moved in a profound and melancholic way by the new perspective the game offered him.

“One of the truisms of, not just modern life, but life anytime, is that you take the world that you’re born into as a sort of baseline, and it’s impossible to know what life was like before. We’re seeing that all across the world, where it’s difficult for modern people to comprehend just how much of the natural world we’ve lost,” said Lund. “I really felt playing Red Dead Redemption 2 that I was transported to a place where nature was different, where the world was different. As manufactured as it was, that sensation of abundance, the ‘everyday-ness’ of nature, the ever-presence of nature, is not something we feel in the same way anymore. Red Dead Redemption 2 gave me what felt like a glimpse of that.”

Not all eco-games are so fantastical. Many are grounded in reality. And, as our corporeal worlds become more anxiety-inducing, virtual ones can reinstate a sense of control.

In Green New Deal Simulator (2023), you play as the secretary of a new, powerful U.S. government department. You must implement real-world technologies and policies like wind and solar farms and the rollout of EV infrastructure, to decarbonize the country. If unemployment breaches a critical point, the government is cooked; fail to reach zero emissions by 2050 and it’s the country itself that is cooked. The game takes policies and technologies that most people know in the abstract and shows how they might practically fit together. I’d helped model a solution to climate disaster; what is usually so overwhelming became a little bit more manageable.

Its creator, Paolo Pedercini, associate professor of art at Carnegie Mellon University who makes games under the alias Molleindustria, has long diagnosed the ills of capitalism through interactive entertainment: Phone Story (2011) took aim at the global supply chain of consumer electronics; Oiligarchy (2008) skewered the neocolonialist practices of the petroleum industry. In recent years, his work has pivoted towards depicting alternative futures, though, he stresses, he’s not interested in wooly climate metaphors or postapocalyptic scenarios that frame societal collapse as “entertaining” or “desirable.” Rather, Pedercini seeks to capture imaginations through tangible scenarios situated in clearly defined spaces. “The key is the specificity of being near-term, not just showing a beautiful world working differently,” he said. “You can do that but it’s even better if you’re sharing the transition of where we go from where we are.”

“I was transported to a place where nature was different, where the world was different.”

Joost Vervoort, an academic and game maker, agrees. His upcoming title All Rise is inspired by his time volunteering with the Dutch activist group Fossielvrij (Fossil Free), which successfully campaigned for one of the biggest pension funds in the world, ABP, to divest 15 billion euros out of fossil fuel companies. Fossielvrij had planned to take ABP to court (in the end, it didn’t have to), and that planted the seed of a game in Vervoort’s mind: one in which you play as an activist lawyer fighting climate cases. In the first chapter, you play as Kuyili, a lawyer who successfully fought for a river in Kerala to be granted legal personhood. Now, the river is polluted beyond repair, so she is taking those responsible to court for murder.

Vervoort described All Rise as an “inappropriately joyous game about climate action.” Why inappropriate? “It’s so dour and depressing thinking about the state of the world with climate change,” he said. “Games can show how joy and playfulness are also part of climate action.” Like Pedercini’s Green New Deal Simulator, it makes fraught, messy processes feel distinctly achievable. “[These games] can be a way to give people hope and agency,” said Vervoort, “To show that it’s not just hard work, but also how it works interpersonally and organizationally. What does it take in terms of imagination, willpower, and emotions?”

In 2023, the climate crisis unleashed unprecedented floods, wildfires, and droughts, catalyzing the start of what felt like cascading human crises: food scarcity; displacement; economic turmoil; large-scale, on-the-ground conflict. In the face of such discord, video games, even those made by large corporations hesitant towards contentious politics, will likely get more radical in their responses. The medium has forebears to draw upon. Final Fantasy VII (1997) is arguably the great ecological story of our time, putting players in the shoes of an eco-terrorist cell called Avalanche who, at various points, blows up fictional mako reactors belonging to a nefarious energy company called Shinra. In 2024, it still feels all too relatable. Last year, Avatar: Frontiers of Pandora (2023), an open-world take on James Cameron’s sci-fi movie franchise, tasked players with a similar mission of sabotage. Playing as one of the Naʼvi, you routinely reduce the colonizing humans’ extractive infrastructure to rubble in a bid to restore ecological balance.

The movie, How To Blow Up A Pipeline (2022), and novel, Ministry for the Future (2020), are rare works in each of their respective mediums that give you, the viewer and reader, a glimpse of what might bring about change in our climate circumstances. Video games are perhaps better suited to these types of process-oriented narratives, narrowing choice and expanding it, showing cause and effect in a manner that is arguably more mutable and visceral than these other art forms. In Avatar: Frontiers of Pandora, the effect of transforming scorched, ashen earth back into lush forest through the power of political violence is cathartic, verging on revelatory.

It would be foolish, however, to assume that players, particularly youngsters, will unthinkingly absorb the messages from these ecological games. There is a growing divide within Gen Z; women are becoming more progressive, open to ideas such as environmental justice; men, on the other hand, are only becoming more conservative. As a long-time incubator of rightwing politics, the online culture of video games is, in part, widening this chasm. Alongside the growing crop of environmental games, it would be wise to predict a reaction in the opposite direction, if not from game makers themselves then from companies like Shell, which has already used Fortnite to market fossil fuels to kids. These games, then, are set to also become cultural battlegrounds.

Alenda Y. Chang, associate professor of film and media studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara, and author of Playing Nature: Ecology in Video Games, doesn’t think that players will passively accept a game’s messages. Rather, games interact with ideals and values a player already holds. What video games can do, Chang opined, is “meet students where they are… they might not radicalize them but they could subtly shift their viewpoint or spark curiosity about something.”

Perhaps, as per my experience with Alba: A Wildlife Adventure, they spark curiosity in the local avian population. Maybe, having explored the “eco-socialist, solarpunk society” in Pedercini’s forthcoming project, players will seek out alternative means of social organization. These video games and their stories are possibility spaces that ask us to experiment and enact, all while fostering a healthy, and perhaps underrated, sense of adventure. Such qualities are vital as we collectively imagine a greener world, one in which nature, the climate, our way of living, and the games we play, emerge fundamentally reconfigured.

Creative Director Eden Yeung Creative Agency Persephone CGI Artist Rodolfo Hernandez Stylist Cece Liu Make-up Artist Laramie Hair Stylist Dylan Chavles Art Director Guido Milani Casting Director Shawn Dezan Manicurist Misha Elle Lighting & Retoucher Patrick Chen Lighting Assistant Ariya Akhavan Styling Assistant Jena Beck Model Saibatou Toure (Fusion)

From Pixels to Politics: How Video Games Can Inspire a Green New World