Words by Mohammad Asif Khan

photographs by Abhishek Khedekar

Inside a cavernous, tin-roofed warehouse in northern India, 42-year-old Madhuri sits on a wooden crate surrounded by mountains of discarded clothes. Her hands move quickly, separating fabric by type: cotton here, wool there, synthetics in another heap. Sometimes she pauses. A velvet coat, still faint with perfume, makes her smile. “I imagine how people in the West must dress, wealthy and stylish,” she told Atmos. “For us, these things are a luxury.”

For nearly three decades, this has been her work: judging the weight, texture, and color of the world’s waste, and tossing it into the right pile. Each morning, bales of compressed clothing arrive by truck, having traveled by ship from U.S. and European donation bins, through the ports of Kandla and Mundra, and finally into Panipat’s warehouses. What begins as waste in much of the Global North then finds a new life in the historic city, fueling an economy that sustains tens of thousands of families.

Once dismissed as a “graveyard of rags,” Panipat has today reinvented itself as the backbone of India’s recycling trade. By some estimates, Panipat processes more than half a million tons of used clothing every year, making it one of the world’s largest textile recycling hubs. The city’s output of yarn and blankets is so vast that its recycled goods end up in IKEA showrooms, Walmart aisles, and refugee camps across Africa and the Middle East.

But this vast recycling hub comes at a cost. Lax regulation has left a trail of health hazards for workers and residents, while shifting tariffs threaten to unravel the fragile industry. In other words: As Panipat powers the global push for circular fashion, its workers live with the fallout.

At Prem Cottex, one of Panipat’s largest recycling units, the process begins with sorting. Workers open bales of used clothing and spread the contents across long wooden tables.“Every piece of cloth has a journey,” said Ritesh Garg, director of Prem Cottex. “It was worn by someone in New York or London, and now it’s here on a table in Panipat. We give it a second life.”

Cotton and wool are shredded into soft threads, while synthetics undergo the same treatment after workers strip out zippers, buttons, and linings. The fibers are then combed smooth and spun into yarn of varying thickness—heavy for carpets and rugs, lighter for blankets and bedsheets.

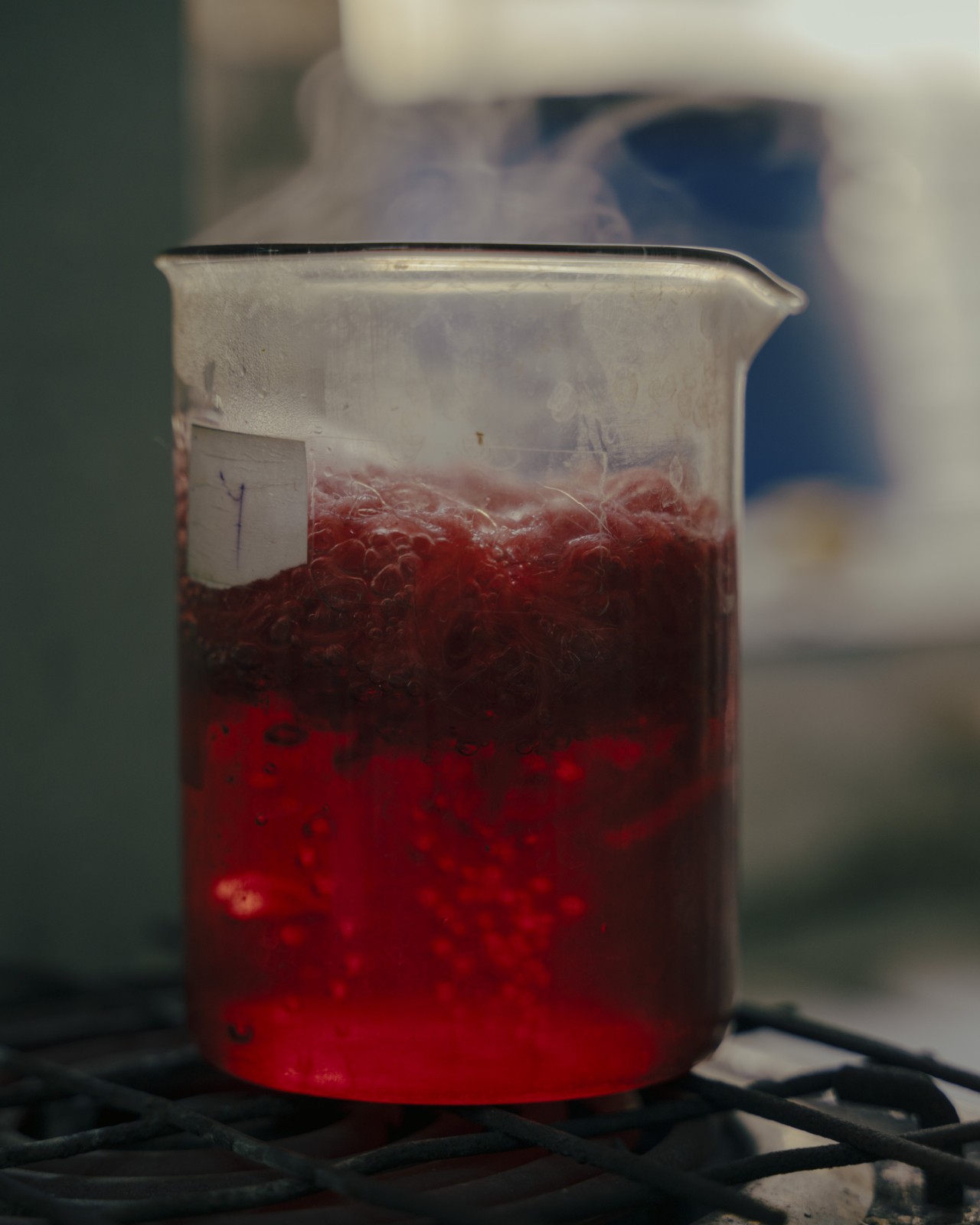

Color sorting reduces the need for intensive dyeing; but when required, fibers are dipped in large vats of natural and synthetic dyes before being rinsed, dried, and rolled into spools. From there, artisans weave the yarn on handlooms and machines into carpets, rugs, and home furnishings, their patterns ranging from traditional florals to modern geometrics. Finally, the textiles are sheared, brushed, washed, and lightly oiled for sheen and durability.

“We are not just recycling,” Garg said. “We are closing the loop. Waste comes in, it becomes a product, and then it goes back. But that loop is breaking now, because tariffs mean fewer bales are coming in, and fewer products are going out.”

Upcycling is often praised as a win-win: Environmentalists hail Panipat as a model for circular fashion, pointing to its ability to extend the life cycle of garments and divert millions of pounds of waste from landfills each year. But for the workers who revamp the world’s castoffs, every day on the job carries serious health risks. More than 200,000 people work in Panipat’s textile sector, many pulling long shifts in suffocating conditions. Dust and fibers fill the air, and the flimsy masks workers wear offer little protection. Coughing, skin rashes, and irritated eyes are routine. Many eventually develop serious respiratory illnesses. Few can afford medical care.

On the floor of Prem Cottex, 23-year-old Vikas feeds secondhand clothing into shredding machines, where steel blades grind old fabrics into spindly fibers. “It makes it hard to breathe sometimes,” he said. “But if orders drop, our hours are cut first. Less work means less pay.” His job also requires checking that each spool in the spinning machines keeps turning. If a thread breaks, production slows. “When that happens, our wages fall,” he added. “We don’t have contracts or insurance. Every mistake affects us directly.”

Doctors in Panipat say they routinely see weavers and spinners with chronic lung disease by their 30s. Others suffer burns, crushed hands, or hearing loss from the din of shredding machines. Rekha, a young woman at the loom, says she often feels dizzy. “But if I stop working, my family goes hungry,” she added. “There is no choice.”

The danger isn’t confined to factory walls. Wastewater from dyeing units runs untreated into canals and wells, seeping into drinking water and damaging crops. Stomach infections are common, and children miss school from repeated illness. Each winter, when Delhi’s air grows toxic, dye houses across Panipat—which lies about 53 miles from the capital—are singled out as culprits and ordered shut, leaving families without wages. “People call it circular fashion,” Garg said. “But on the ground, it is families breathing dust, children working in sheds, and rivers running black with dye.”

“Every piece of cloth has a journey. It was worn by someone in New York or London, and now it’s here on a table in Panipat. We give it a second life.”

But these harms are preventable. Simple safeguards—like regular health screenings, proper protective gear, improved air circulation, and more secure waste disposal—could dramatically reduce the toll. As things stand, and without enforceable standards, responsibility falls to individual workers with little power to demand change. Fair fashion activists describe this imbalance as a form of waste colonialism: Rich countries export their waste in the name of sustainability, while poorer communities pay the price. But many also stress it doesn’t have to be this way. With fairer trade terms and real investment in cleaner technologies, recycling hubs like Panipat could support livelihoods and drive a circular economy without sacrificing public or environmental health.

“There should be rules that hold employers accountable for the health of their staff,” said one advocate familiar with the region’s factories, who spoke on condition of anonymity. “The industry relies on these workers, but their well-being is treated as non-essential. Without stronger laws, the pattern of poor health and exploitation will continue.”

If dust and untreated wastewater are the silent dangers of Panipat’s textile economy, trade wars are the sudden shocks. And the latest hit has been devastating.

Earlier this year, the U.S. imposed a 50% tariff on Indian textile exports, doubling an earlier levy. Washington cast it as retaliation for India’s high tariffs, its purchases of Russian oil, and its refusal to back U.S. positions on Ukraine.

Textiles now face the steepest tariff burden of any sector—close to 64%— leaving Panipat, which is heavily dependent on imports, especially exposed. The town was already under strain: The war in Ukraine slowed demand in Europe, while rising freight charges and inflation cut margins. Now, new tariffs have pushed the industry into its toughest period in decades.

Orders for yarn and blankets dried up almost overnight. Supervisors cut overtime, and layoffs became a subject of hushed conversation on factory floors. For workers like Madhuri, the impact was immediate. “If I lose even a couple of days’ wages, I have to choose between food and school fees,” she said. “There is no safety net for us.”

The scale of the blow is stark. Panipat exports about $2.4 billion in textiles each year, roughly 60% of it to the U.S. With the new tariffs, competitors in Pakistan, Bangladesh, Turkey, Vietnam, and Italy are poised to capture a crucial market share. “Orders are on hold from the United States,” said Gaurav Chugh, director of operations and development at Rugs Creation, a Panipat exporter. “Buyers are hesitant. They’re worried about cost, and we are left waiting.” If demand keeps falling, he warns, layoffs will be unavoidable. “We don’t want to cut jobs, but if orders don’t come, there is no choice. The government should step in with some support.”

Inside the mills, the downturn is already visible. Spinning machines are already running slower due to fewer orders. Children—who should not be working at all—shoulder some of the burden. In a dimly lit shed, 12-year-old Imran pries zippers off old jeans, his fingers raw from sharp edges. His father lost his job at a loom last month, and the family depends on Imran’s small earnings. “It’s not uncommon,” one worker said. “When adults are laid off, their children step in. Nobody asks questions.”

Across the border, Pakistan has seized the opening. A major textile hub in its own right, the country recently secured reduced tariffs on exports to the U.S., giving its mills easier access to the market just as India’s share shrinks. China remains a constant pressure, producing faster and cheaper with highly automated machinery and world-leading infrastructure.

“If they want us to keep this work alive, they must also keep us alive. We can manage long hours, but not without safety, not without dignity. This crisis should change something; otherwise, what are we working for?”

Panipat has survived for decades on the thin margins of globalization, transforming the detritus of fast fashion into something useful—even beautiful. But the twin pressures of worker exploitation and geopolitical rivalry now threaten to unravel the system altogether.

Advocates argue that the crisis presents an opening. Now is the time to invest in clean energy, enforce stricter labor standards, and negotiate fairer trade terms, to cement Panipat’s position as a beacon for what truly circular fashion looks like: one that sustains the planet and the people who make it possible. But absent reform, the city risks becoming yet another cautionary tale of how the costs of “sustainability” are pushed onto the most vulnerable.

“If they want us to keep this work alive, they must also keep us alive,” said Madhuri. “We can manage long hours, but not without safety, not without dignity. This crisis should change something; otherwise, what are we working for?”

The High Price Of Circular Fashion In India’s Recycling Capital