Words by Daphne Chouliaraki Milner

Photographs by John Yuyi

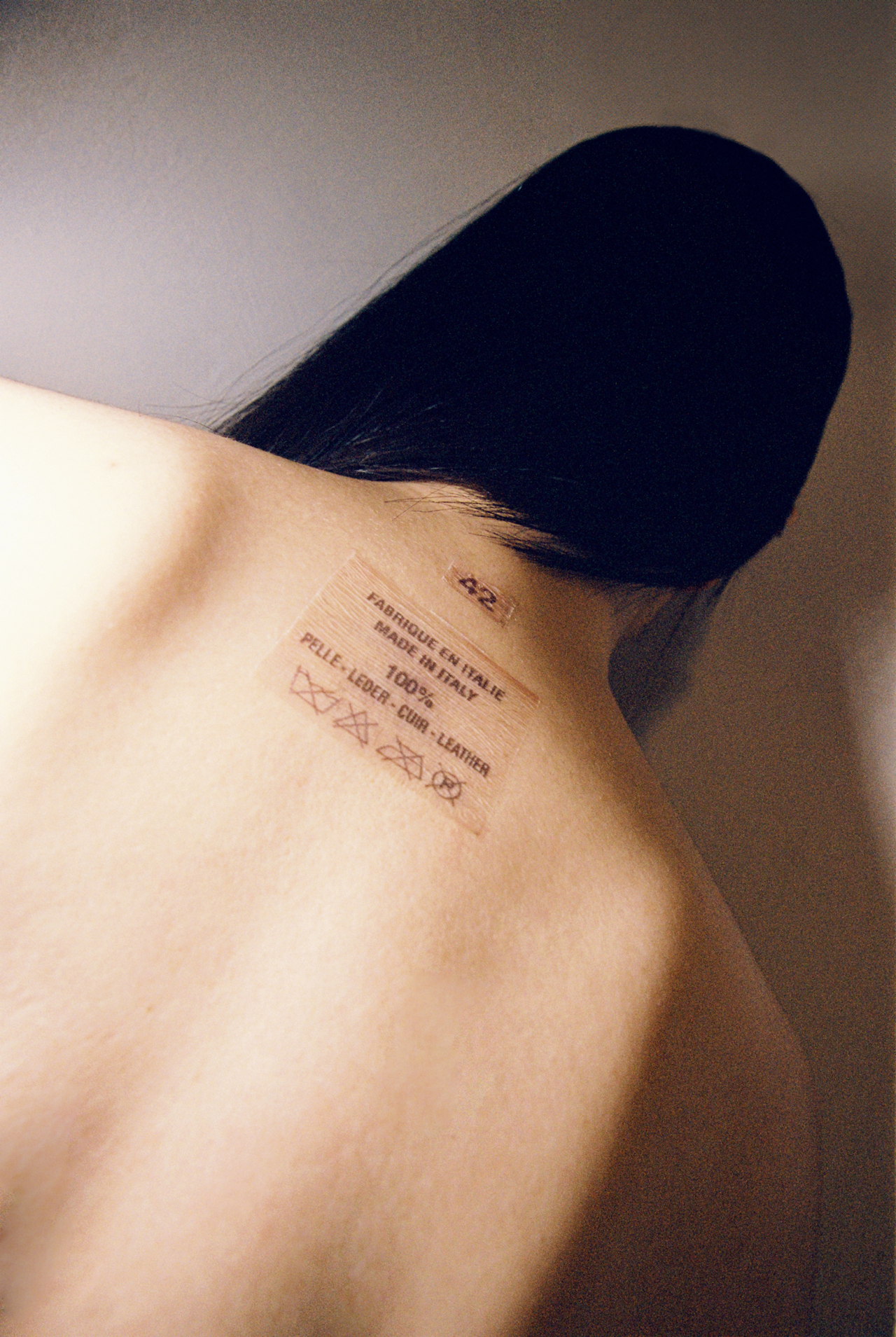

The fashion industry produces around 100 billion garments every year, and almost no one can tell us where they all go. Once produced, a garment disappears into the market, which obscures the steps taken to get the garment there but doesn’t eliminate the damage incurred along the way. Brands often struggle to answer basic questions about their own products: Where was it made? What is it made of? How much carbon or water did it consume? Who stitched it, and under what conditions? Can it be reused, or will it end up in a landfill?

Now, the European Union is preparing to mandate answers in a sweeping move toward greater industry transparency. As part of the forthcoming Ecodesign for Sustainable Products Regulation, which is set to take effect in 2027, every garment sold in EU member states will be required to carry a digital product passport: a scannable record that traces an item’s full lifecycle. “If we want to have less impacts on climate change, the fashion and textile sector needs to be part of the solution,” said Lars Fogh Mortensen, an expert on circular economy, consumption, and production at the European Environment Agency. “With digital product passports, the aim is to try to reduce the damage.”

The details are still being fleshed out, but the idea is that each passport would contain a trove of critical data about material sourcing, chemicals, water and energy use, and carbon footprint. Scan a QR code, and you could see exactly what your clothes are made of and how far they’ve traveled. “It’s essential that the digital passport covers the whole life cycle,” said Mortensen. “We’ll have to see where it lands, but from a substance and analytical perspective, it should be as broad as possible.”

The EU is still finalizing the details of its product passport legislation, but the ripple effects could be global, according to Mortensen. If brands are required to meet strict quality and transparency standards to access the EU, many may apply those same practices elsewhere by default. Some see this as a tipping point for traceability in fashion. Others aren’t convinced just yet.

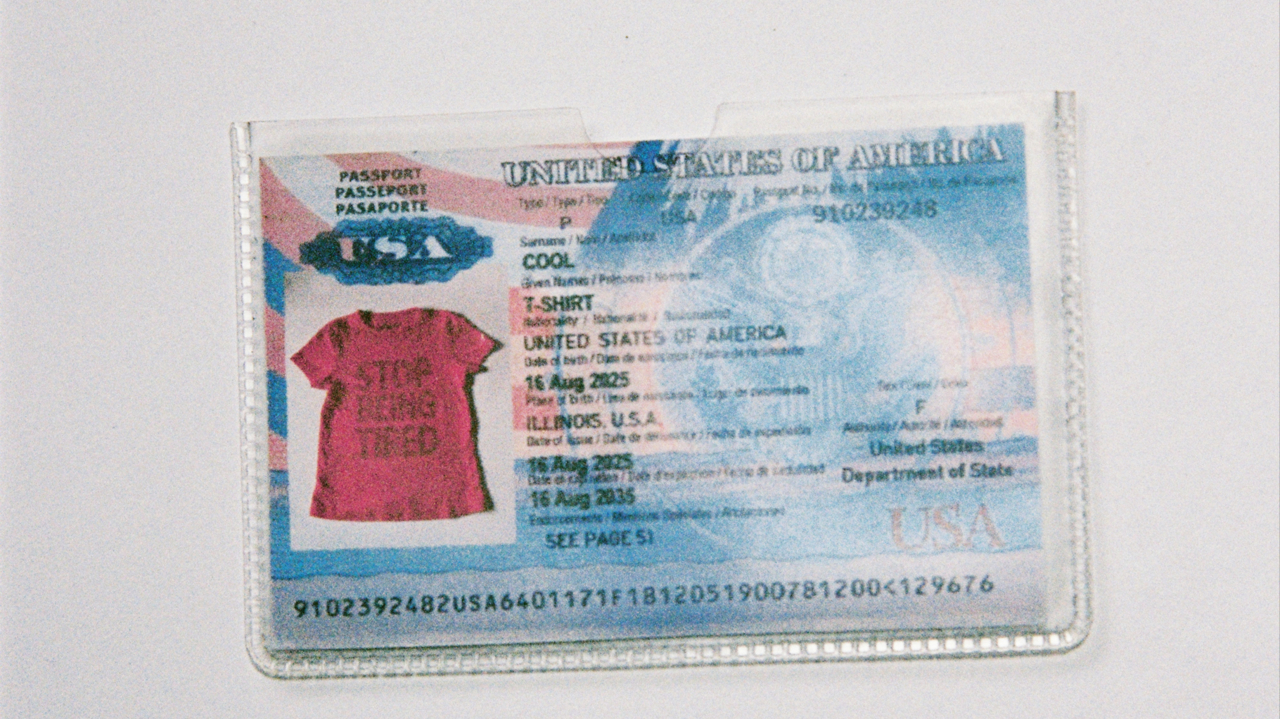

“It’s still early days, but at the moment it’s not that much more than a digital hang tag,” said Tina Wiegand, lecturer at Hof University with a focus on sustainability, circular economics, and digitalisation in the European textile and clothing industry. “What I hope for is a passport that shows me as a consumer the whole supply chain, so that I can make informed decisions and compare two T-shirts on their sustainability impact.”

For these passports to live up to their promise, they must work for everyone: regulators and consumers, yes—but also for the people who make our clothes, as well as those who repair and recycle them. As the industry approaches a critical inflection point, one that will determine whether this tool drives real accountability across the supply chain or simply reinforces existing blind spots, what happens next depends on whose voices are heard. There’s still time to get this right, and the people who live and work inside the system are already pointing the way.

While the EU’s digital product passport legislation is primarily focused on environmental performance, many advocates argue it’s a rare opportunity to embed social justice into product design. With the right framework, passports could surface the conditions under which garments are made, making visible the labor practices that currently go unmonitored. That might mean requiring companies to disclose wages paid in relation to local living wage benchmarks, flag whether workers are unionized, and offer links to grievance mechanisms tied to specific factories in cases of human rights abuse or environmental harm.

“This could be a step forward,” said Anna Bryher, policy lead at Labour Behind the Label. “We spend so much time arguing over what’s actually happening [in this industry], rather than where we need to get to. If digital product passports could be one piece in getting that baseline established, then that would help.”

Establishing that baseline will require more than vague targets or unverifiable claims, and that means holding companies to a level of transparency they’re not used to. Carbon footprints, for instance, should reflect the actual emissions associated with a product’s supply chain—not generic estimates. Similarly, chemical disclosures should include clear guidance on the frequency and reliability of testing to ensure credibility.

The same applies on the consumer end. For people to use passports meaningfully, the data has to be actionable. In addition to outlining where a product came from or how it was made, product passports could include detailed information on how to care for it: How to wash it with minimal environmental impact, where to repair it, or how to return it for recycling. QR codes could also lead to interactive maps of nearby repair centers or single-click take-back options, according to Wiegand, in order to help shift consumption patterns away from disposal and toward longer use.

Some experts see even more creative possibilities. Product passports could embed step-by-step instructions for how to upcycle old garments. For example, a pair of jeans could include a downloadable pattern showing how to turn it into a bag—based on information only the original designer might know. Such reuse templates would not only extend the life of garments, but also incentivize brands to design with circularity in mind. That kind of feedback loop is still missing, advocates say.

“There’s a high chance that if you’re a designer at H&M, your items will end up here,” said Elmar Stroomer, who alongside Alex Musembi cofounded Africa Collect Textiles, which recycles and repurposes textiles in Kenya and Nigeria. “So the least they can do is [design] with us [in mind to help us] process their items using the skills and limited tools we have.” While Europe benefits from advanced tools—many funded by profits generated via the secondhand clothing trade—recyclers in the Global South, who do not have access to the same funding, often rely on scissors and expertise built from years of practice.

That disparity is exactly why infrastructure investment must accompany innovation. “If [a country in the Global North] has QR code scanners for these passports, they must make sure one is also sent to Africa,” said Stroomer. “All of these innovations need to be duplicated. One should always go to the place where the product actually reaches its end of life. It’s the only way to ensure the fashion chain is made circular and not just extended.”

For digital product passports to deliver more than surface-level transparency, they must be anchored in credible, enforceable systems. That begins with acknowledging the global imbalance in who creates these policies and who lives with their consequences. “What all these policies fail to recognize is, first of all, how privileged these countries are to make such rules in the first place—and to decide what can and cannot be sent when infrastructure is lacking,” said Stroomer. “But also how much impact these policies actually have on true circularity for us all, especially communities in the Global South, and for the planet.”

The reality is that corporate success is currently driven by short-term profit, which means very few companies are willing to absorb the cost of doing the right thing. That’s why voluntary action isn’t enough, says Maxine Bédat, director of the New Standard Institute. “Transparency is the first step, but it is not the last step,” she said. “I worry that transparency becomes the end in itself, especially once legislation is passed and governments say, We need years to implement this before doing anything else.”

Bédat and all other experts Atmos spoke with insisted that digital product passports will only work if they’re part of a broader policy framework—one that mandates action off the back of data collection. “A company doing the right thing shouldn’t be at a competitive disadvantage,” said Bédat. “We need clear, stable rules that allow the market to invest in better relationships with suppliers. Otherwise, we’re wasting time.”

That framework must also align with how circularity actually functions in the real world. “What the digital product passport is doing is getting real-time data to say, This product was resold once and then recycled. That real-time data has never been possible before, but it’s actually the key to accountability,” said Natasha Franck, founder and CEO of EON, the digital product passport solutions company piloting the EU’s legislative framework. “A person doesn’t have a different license plate every time they enter a different state. They’re registered as the same person. The same will now go for products, and this will also bring accountability. As in, Why is this product showing up in this place? And who’s responsible for this product now that it’s here?” she added.

To reverse a world built on disposability, solutions as ambitious as the problem is big are needed: policies that redistribute power across the supply chain, initiatives that center workers’ voices, and global infrastructure that ensures circularity doesn’t stop at Europe’s borders.

A first step toward that scale of restructuring requires defining what credible data actually looks like and who is responsible for verifying it. Because without uniform definitions and consistent oversight, material passports risk giving the illusion of progress without changing how anything is actually made or discarded. “What we absolutely wouldn’t want,” added Bryher, “is for this to be left to auditing firms and voluntary brand participation. That would open the door to further greenwashing.” While auditing firms are technically third-party entities, Bryher notes that they are often hired and paid by the brands themselves, a dynamic that compromises impartiality and weakens accountability. Instead, experts say verification must involve entities with no financial ties to the companies being assessed, with clear, enforceable guidelines developed in partnership with civil society, labor organizations, and frontline communities.

There’s still a long way to go before the EU finalizes its framework, but much will depend on who sets the standards. “If there were clear supply chain mapping and brand-level responsibility, like knowing the volumes of products different brands produce in different locations and where those products actually end up, it could support the conversation around waste colonialism,” said Bryher. “It would help establish a shared baseline: What is the problem, and how exactly can brands be held more accountable for years to come.”

Talent Stein Shen Prop design John Yuyi

This story first appeared in Atmos Volume 12: Pollinate with the headline, “The Case for Giving Garments a Passport.”

The Case for Giving Garments a Passport