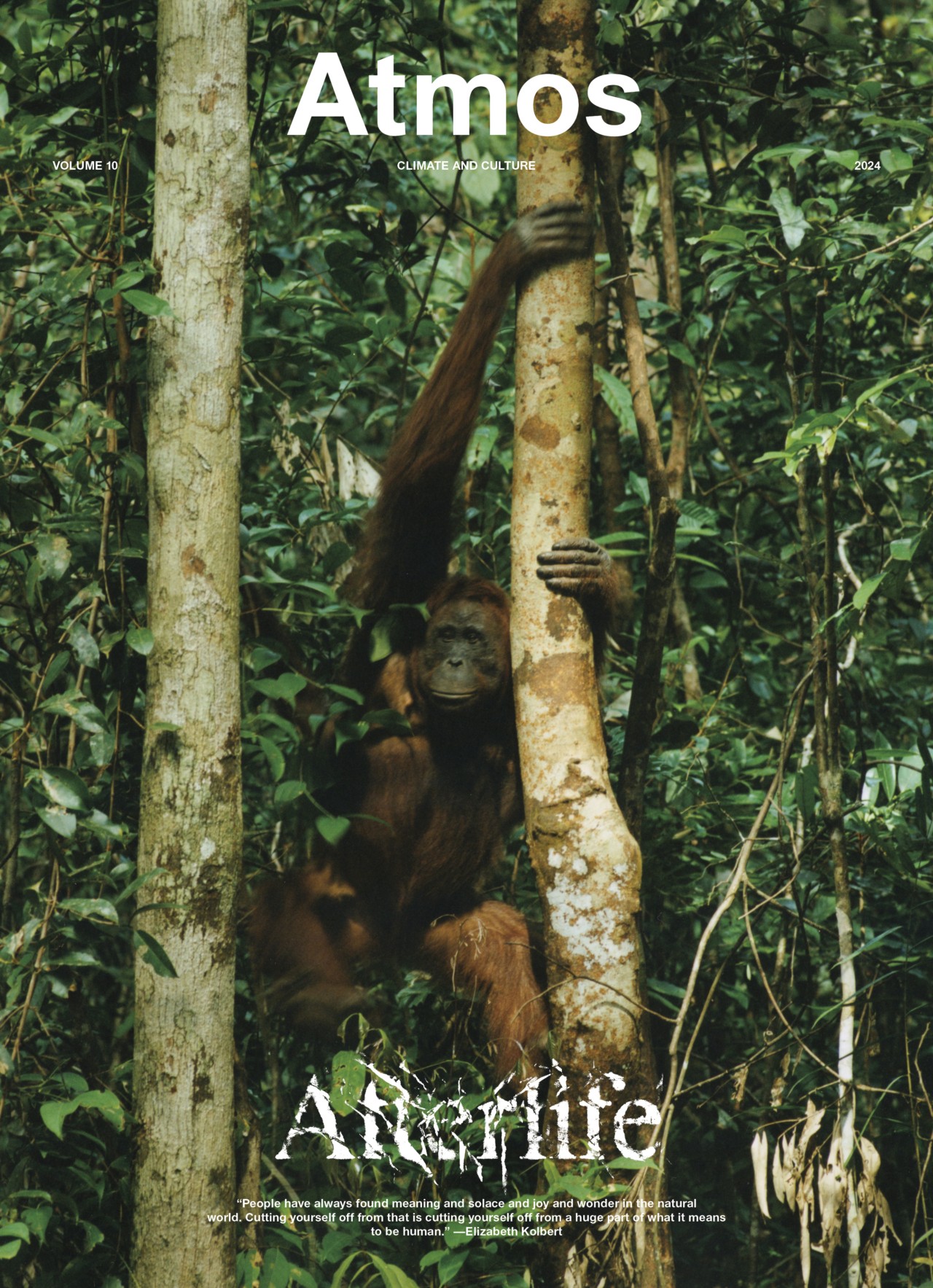

These photographs by Stefan Dotter illustrate two distinct landscapes in Indonesia: the biodiverse rainforest of Borneo and the overwhelming pollution in Jakarta.

Words by Whitney Bauck

Photographs by Stefan Dotter

Maybe you’ve noticed it: When you take a long road trip, your car windshield isn’t smeared with bugs by the end of the drive the way it would’ve been when you were a kid. The sound of birds and frogs in the forest isn’t quite as deafening as it used to be. The coral reef you grew up snorkeling over seems less colorful and lively now than in your memories.

Or maybe the process has been too quiet, too out of the way of your daily life, for you to see it in real time. But wherever you live in the world, it’s happening: The pulsating richness of the tree of life on this planet is withering, with some branches drying up and breaking off completely.

This dying off is known as the biodiversity crisis, and it’s been rapidly accelerating for as long as you’ve been alive. Alarmingly often, our species is to blame: A recent study found that groups of animal species are vanishing 35 times faster than expected due to human activity, whether that’s burning fossil fuels that heat the planet to power our cities, cutting down forests to build suburbs, or converting wildlife habitat into agricultural plots.

Today, 48% of the world’s species are declining. It’s thought that one million animal and plant species are threatened with extinction (to say nothing of the under-studied kingdom of fungi). Each species wiped off the map represents millennia of evolutionary processes, snuffed out far more quickly than they can be replaced.

But even for humans disinclined to mourn the demise of the Tasmanian tiger, Mexican vaquita, or the humble Lake Pedder earthworm, extinction should be a cause for alarm, if only out of self-interest. Our own existence is dependent on the rich tapestry of other forms of life on earth, from the plants that provide us with oxygen to the fungi that cycle nutrients to the insects that pollinate our food.

As E. O. Wilson once put it, “If we were to wipe out insects alone, just that group alone, on this planet—which we are trying hard to do—the rest of life and humanity with it would mostly disappear from the land. And within a few months.”

So how are we to live in the face of overwhelming ecological death that threatens all the vibrant species we share this planet with, from the smallest insect to the most towering tree?

One warm summer day, with crickets springing from the grass and the memory of a recent visit from an armadillo fresh in my mind, I sat down to discuss that question with two people who have shaped the public imagination around extinction and our relationships with other species: Elizabeth Kolbert and Craig Foster. Kolbert is a staff writer at the New Yorker and the author of Pulitzer-prize winning book The Sixth Extinction, perhaps the most definitive work on the subject in the English language. And Foster is one of the filmmakers behind and the protagonist of the Oscar-winning documentary film My Octopus Teacher, which chronicled his relationship with an octopus in the kelp forest near his home on the coast of South Africa, as well as the author of the new book Amphibious Soul: Finding the Wild in A Tame World.

We met virtually across three time zones to discuss extinction, wonder, and the weight of living in the Anthropocene.

Whitney Bauck

Where did the seed of interest in extinction and biodiversity loss come from for each of you?

Elizabeth Kolbert

I was interested in the amphibian crisis. Amphibians are a diverse, ancient group of organisms, and many species were in big trouble. As a journalist, that seemed like a huge story that wasn’t getting enough attention, and it opened out into an even bigger story that took me years to explore. It seems the biggest story of our time—what’s happening to all the other species with whom we share this planet—and in general, it’s not good.

Craig Foster

For me, it started with trying to teach myself to track animals underwater and getting to know the Great African Seaforest. At a certain stage, I was focusing on one animal, the octopus. She has over 50 prey species, lots of predators, and all these amazing animals that clean up after the kills. When you get to know that one animal, you’re actually getting to know well over 100 species that are interacting directly with the cephalopod.

In my part of the world, the kelp forest is actually growing in size. We’ve got some biodiversity loss in certain areas, but the invertebrates are more numerous than 100 years ago.

But then reading about other parts of the world, you start to worry.

Whitney

Craig, you became best known for building a relationship with one specific animal in one specific ecosystem. Whereas when I look at your work, Elizabeth, I see a lot traveling to different places that we often don’t hear from and bringing back these stories. I’m curious how the two of you think about these different approaches.

Elizabeth

I have usually tried to get out in the field to encounter other creatures. That is complicated when your subject is extinction: You’re out there, and maybe the creature isn’t there—that’s the whole point. You end up relying a lot, in journalism, on people as the medium between you and these creatures who cannot speak to you in the language of humans. I have usually relied on people to interpret what they’re communicating.

Craig

It is so valuable to go to the same place again and again. Because you peel back the layers, and at a certain point, you do feel like you’re in dialogue with the wild. It’s the most incredible feeling. It doesn’t happen all the time, but these moments of grace, where you feel this incredible dialogue, are very powerful.

But it also gives you quite a myopic view, because you’re going to this special place where the ecosystem is in fairly good shape. And you start to imagine that the whole planet is like that. Or you start to see this shifting baseline, where you think everything’s okay, but you haven’t realized it’s changed quite radically from what it was.

I was very fortunate to go to this island off East Africa. I was absolutely shocked when I went there at the level of biodiversity, because it’s a near-pristine environment. And I realized that in the kelp forest [near my home], although the invertebrates were in good shape, many of the larger fish and predators had taken quite a hard knock.

Looking at all these different places, you get an amazing perspective. But it does help to immerse in one place, because that kind of binds you and connects you to an environment, and it feels like a second home.

I’ve found that in these places of incredible biodiversity, my whole psyche changes when I’m in that incredible life force. Elizabeth, do you feel that as well?

Elizabeth

I live in the Northeastern U.S., which is a part of the world that was glaciated as recently as 10,000 years ago. It has not been a very biodiverse part of the world, since all the species have had to return in the last 10,000 years. It’s also a very disturbed landscape. Everything was farmed 100 to 200 years ago, the large predators are gone, the large mammals are gone. It’s a very depauperate environment for all sorts of reasons.

But when you are fortunate enough to get to a place that at least seems intact, that profusion of life is astonishing. One is at a loss for words; it’s beyond human language. There’s a complicated calculus here: If everyone went there, obviously it wouldn’t be like that. But if everyone saw it, I think people would have more of an appreciation for what’s at stake.

Craig

That’s the feeling I’ve had. I wish every person on the planet could experience it. Five thousand years ago, every single human that ever lived would have experienced that. This incredible birthright that’s come down 300,000 years has been taken away from us—that feeling of being in this extreme biodiversity, extreme life, is really profound. And absolutely terrifying, with what we know about the environmental crisis. I had this strange feeling of exhilaration and then terror, because I can feel how much we’ve lost.

Whitney

If there are these huge stakes, why aren’t we doing more to stop biodiversity loss? Is it that we are disconnected and a lot of us aren’t actually seeing it in real time, even though it’s happening at a speed that is shocking in the context of geologic time?

Elizabeth

If you just take one threat to biodiversity, which many people would also recognize as a threat to human civilization—climate change—why aren’t we doing more? The answers are very complicated. They have to do with the enormous, complex systems that are our economies and our ways of living that have developed over centuries.

Many people would point to Western values as minimizing our relationship to the natural world. I grew up in New York. You saw some pigeons, but you didn’t see a lot of the natural world. And if you were living in New York your whole life, you would see that it was getting hotter, but I’m not sure you’d see a tremendous amount of change to the natural world, because everything there has either been planted or transposed by humans.

Many millions of people live in environments like that. That shields us in a way. And I think that the notion that the whole fabric of life on the planet can unravel and there is a potential for really catastrophic consequences is hard for people to take in when there’s plenty of food in the grocery store for many of us (though certainly not for all of us).

Craig

When I ask people, “What do you think of biodiversity? And how does that connect to your life?” I like to almost frame it as, “What’s your relationship with the essence of life?”—because that’s your life support system. That’s what’s keeping us all alive. That’s the pulse.

And people simply don’t know. They’ll intellectually, at some point, have had that knowledge. But unless you emotionally connect to all these incredible species and see them as kin, as part of the bigger family, it’s very hard to make that connection, especially when you’ve got so many distractions, and you’re trying to feed your family.

Many Indigenous people know this at a very deep level and have spoken profoundly about it. But many people in the West have lost all connection and have no idea that they’re breathing and eating because the biodiversity is still doing all that work.

“The act of connecting with wild animals or plants is a very powerful antidote.”

Whitney

As people who are shaping public narratives around our relationship with the natural world, what are you hoping to accomplish?

Craig

Let’s face it, when you look at the science, it is terrifying. There doesn’t seem to be any easy way out. But I found that just having that knowledge is empowering, because at least you know what you are looking at. It’s far less scary than not knowing.

We have, with the three of us talking, got billions of years of this extraordinary, mysterious evolution that led to us being here. That power, that mystery, that wonder of existence and our consciousness is so overwhelming and so exciting, that the present moment we’re sitting in now is extremely hopeful. Because we don’t really know what’s going to happen.

Elizabeth

I think you’re getting at something profound about storytelling around the environmental disasters of our current moment. The world is an unbelievably fascinating place and many amazing discoveries are being made every day, and I think that that puts us in a really interesting moment. The more we know, the more fascinating and amazing the world is.

At the same time, the more we understand that what we’re doing is very destructive. We’re unraveling, as Craig said, billions of years of evolution. Or maybe we should just say millions, because the things that were around a billion years ago—the bacteria—are probably still going to be here.

But back to your question, Whitney: What am I trying to do? I think it has a very straightforward journalistic purpose: This is happening, and you ought to know about it. But there also is an element of—and I don’t want to be too highfalutin’, because what I practice is journalism, which, as one of my editors said, “is going to be on the bottom of a birdcage tomorrow”—bearing witness. I do think these things should be chronicled. Obviously, the response to, “Wow, we’re destroying the world, and we’re destroying our own life support systems” should be, “Well, we ought to rethink this.”

Craig

My primary focus is trying to connect people emotionally to biodiversity or, as I prefer to say, the mother of mothers. That’s the underlying motivation for almost everything I’m doing. I’m trying to find stories that are interesting and entertaining to try and make people connect to that.

There was some survey where they asked people, “What is your biggest concern?” And only 1% of people talked about the climate crisis and the environmental crisis. It seems that somehow the most important message of our time has not gotten into the psyche of humans. You’d think that as soon as people understood this, everybody would be talking about it, and you wouldn’t be worrying about these other things that are huge in the press that seem to me completely irrelevant.

Elizabeth

In the U.S., we are seeing one really impactful climate-related disaster after another, and it still doesn’t seem to really move the needle. I don’t want to get much into the weeds on domestic politics in the U.S. But that’s another huge factor. It’s no secret that there’s a lot of money being made off fossil fuels in the U.S. and that a lot of jobs depend on that. And that is a very big barrier to any kind of progress.

Craig

Of the 55 countries in Africa, 48 of those countries are involved in fossil fuel projects, and almost all of those projects are funded by the Global North. Much of my family live in India, and they speak a lot about wonderful policies on biodiversity and everything, but underneath all that, these fossil projects carry on. It doesn’t make sense.

Whitney

Something that most of us who write about this come up against at some point is: How do you wrestle with the weight of being human when you do have an emotional connection, or have gotten to go see these places that really inspire a love or reverence for the natural world? How do you wrestle with our species’s place in all of this? Is it possible for us to correct course, and what would it take to do so?

Elizabeth

That’s the $64 trillion question of our time. And I don’t think it has an easy answer. Humans take up a lot of the world’s resources—feeding eight billion people, that’s not nothing. Even if we decided to live in the way that our ancestors lived—which Lord knows, we are not deciding to do anytime soon—there are still many times more people than there were in the days when we might look back to as people having had a much more intimate relationship and sense of guardianship for the natural world.

One of the stories in The Sixth Extinction is how, as people moved around the world, they did in a lot of the large animals in these new places. We’ve been at this project of changing the natural world for a very long time.

Certainly those of us who live in rich countries can’t be telling people who have lived in poverty for generations that they can’t live the way we do. But if everyone in the world lived the way Americans did, the world would collapse pretty quickly. So we are in a tremendous bind.

Even if you are very deeply concerned about the natural world, our values are in conflict with each other. I feel that all the time. Anyone who tells you there’s an easy way of eight billion people living in harmony with the natural world is smoking something very very powerful. I don’t know where this is going, or where or how it’s going to end. But I am personally perpetually terrified.

Craig

When our species went out of Africa, there’s certainly really good evidence for megafauna extinctions. But to balance that slightly, there are some fascinating studies to show that certain Indigenous people actually increased biodiversity in the areas in which they lived. The way most of us live now is obviously so far away from that, but I think that our story of our relationship with our planet has to change at a fundamental level. The glimmer of hope I see is if we can try to draw from incredible people around the world who’ve dedicated their lives to saving species and to conservation.

I agree that we are contradictory. That’s our nature, if you look at our species. Certainly the Indigenous people I’ve worked with closely, they embrace contradiction—they know that’s part of our way. But somehow, in that wonder and mysterious nature of how this has all been put together, I feel there is hope. My sense is that if we put together the best science with the best Indigenous knowledge—this idea of two eyes seeing, one eye seeing through the old ways and the other eye seeing through the science—that is an amazing, powerful tool to bring about this new story, which is really an old story of deep reciprocity with the wild and with animal kin.

Whitney

Wonder is something that I keep coming back to, that’s in some ways more generative for me than thinking about hope. Because you can be terrified out of your mind, based on a very realistic understanding of what’s happening, and still have an encounter that fills you with wonder. How has that shown up in your work?

Elizabeth

That gets back to this notion that we’re learning new and amazing things about the natural world every day, so even if you’re sitting in an apartment in New York, you still have access to a certain amount of wonder. Craig’s movie, which was streamed by many millions, really brought that into people’s living rooms. So on some level, we have more access now than ever before to the natural world—which is kind of contradictory—but through images and words.

I think that you make a really good point, Whitney, that you can be terrified and filled with wonder at the same time. Those are not contradictory, whereas terrified and hopeful maybe are contradictory. I think that is potentially extremely powerful.

Craig

I love that idea of wonder. Just to give a quick example: Yesterday, I was diving quite late. It was getting towards night, and I saw this really strange sight. There’s a fish that jumped off the top of the kelp canopy. It’s a fish I know very well, a giant clingfish or a rocksucker. It’s got an enormous suction pad underneath the body and this huge mouth and huge teeth.

He was able to surf two meters out of the water up in a wave and then stick onto the rock. It’s basically an amphibious fish that can breathe for several hours out of water. They surf up the rocks to hunt limpets. Then they’ll wait for the next wave to come up, and in the fraction of a second, grab a limpet, twist 90 degrees, pop it off, and swallow the thing whole.

You see these kinds of things, and it’s just mind blowing. With the knowledge of what’s happening to the planet, it increases that wonder more radically, because you’re having this biodiversity loss, climate change, all these crises going on. And within that terrifying space, you still see these unbelievable acts of wonder by animals and their extraordinary ability to survive.

That’s why our time is so powerful, because you’ve got this incredible juxtaposition. It puts you a bit on edge for sure, and you feel that scary loss in your solar plexus. But at the same time, the wonder’s jacked up a hundredfold.

Whitney

I see a lot of millennials and Gen Z folks who get kind of shut down. They get the stakes, they get that it’s a catastrophe, they understand the crisis. But the response is to shut down and be like, “This is almost too much, and the reason I’m not engaging is not because I deny it’s happening, but because it’s too overwhelming to think about.”

As people who have wrestled with the weight of the thing, but then maybe have also had some of these experiences of wonder, what would you say to younger folks who are trying to figure out how to live the rest of their lives, knowing that this is the state of the world?

Elizabeth

I have kids who are in that demographic, so I think about it a lot. If you’re shutting yourself off from the world, it’d be like shutting yourself off from human relationships. That’s ill-advised on so many levels.

So I think that even though we live, to quote the great Robert Frost poem, in a “diminished” world—we live in really frightening times—people have always found meaning and solace and joy and wonder in the natural world. Cutting yourself off from that is cutting yourself off from a huge part of what it means to be human. So yes, the terror and the sadness should be part of it, but also the joy and the wonder. I don’t think you can have one without the other.

The natural world is incredibly resilient. It has been around for billions of years. And if you give it a chance, many species in many ecosystems will reorganize and survive. The problem is that we are changing things so fast that we’re not really giving them time. E. O. Wilson had this notion that we’re in this bottleneck, this moment of maximum human pressure on the planet, and that we need to try to get as many species as possible through that bottleneck. He had this idea of how half the planet should be set aside in marine reserves or terrestrial reserves. Not that we’re going to stop change, because change is happening, but to try and give them time to adapt.

Craig

The act of connecting with wild animals or plants is a very powerful antidote. I would say to a young person—and I have a son who’s 22—“Get to know even one animal in your backyard and get to know all the animals that it relies on.” If you get to know these creatures, you get to know all their connections and how the whole biodiversity web works. You can have quite a lot of pain associated with that, because it develops empathy.

But if you go a stage further and get deep into these creatures’ or plants’ lives, something else happens: You become very present. It doesn’t happen that often, but in these moments of grace, the mind sees a bigger picture, it sees into the deep past and the deep future, where everything feels okay. It’s a strange thing.

I think that a lot of the mental health crisis is connected to this feeling of not belonging on your own planet. How can you belong if you don’t feel connected to the other creatures and plants that inhabit it? So I would strongly advise going into that world and getting to know it.

There’s going to be some pain. But there’s also a lot of salvation in that.

SPECIAL THANKS Alam Sehat Lestari (ASRI), Laily Lutfiana Dhia, Danica Evani Pribadi

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

This story first appeared in Atmos Volume 10: Afterlife with the headline “Vanishing Awe.”

Elizabeth Kolbert and Craig Foster: Holding Onto Awe Amid Biodiversity Loss