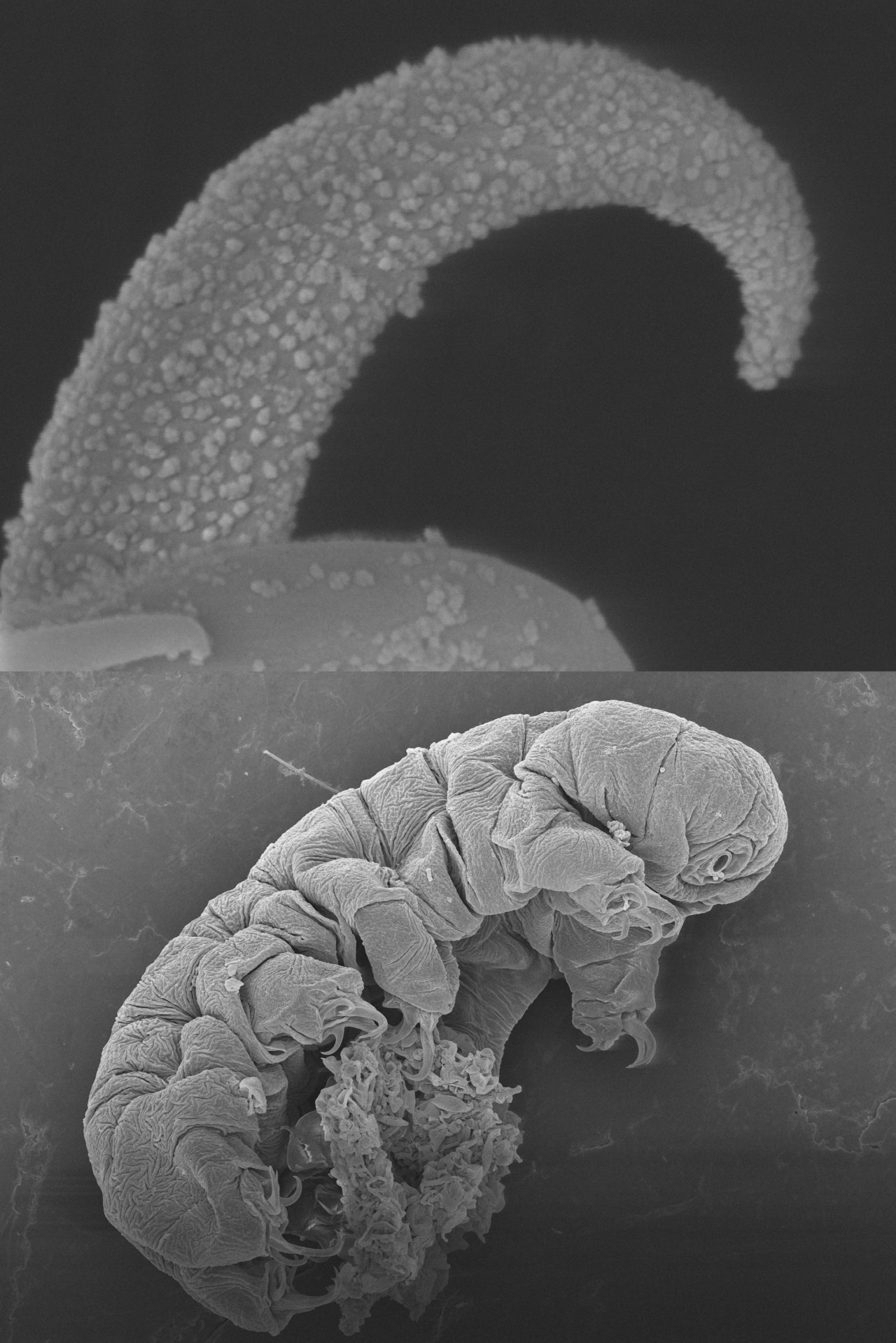

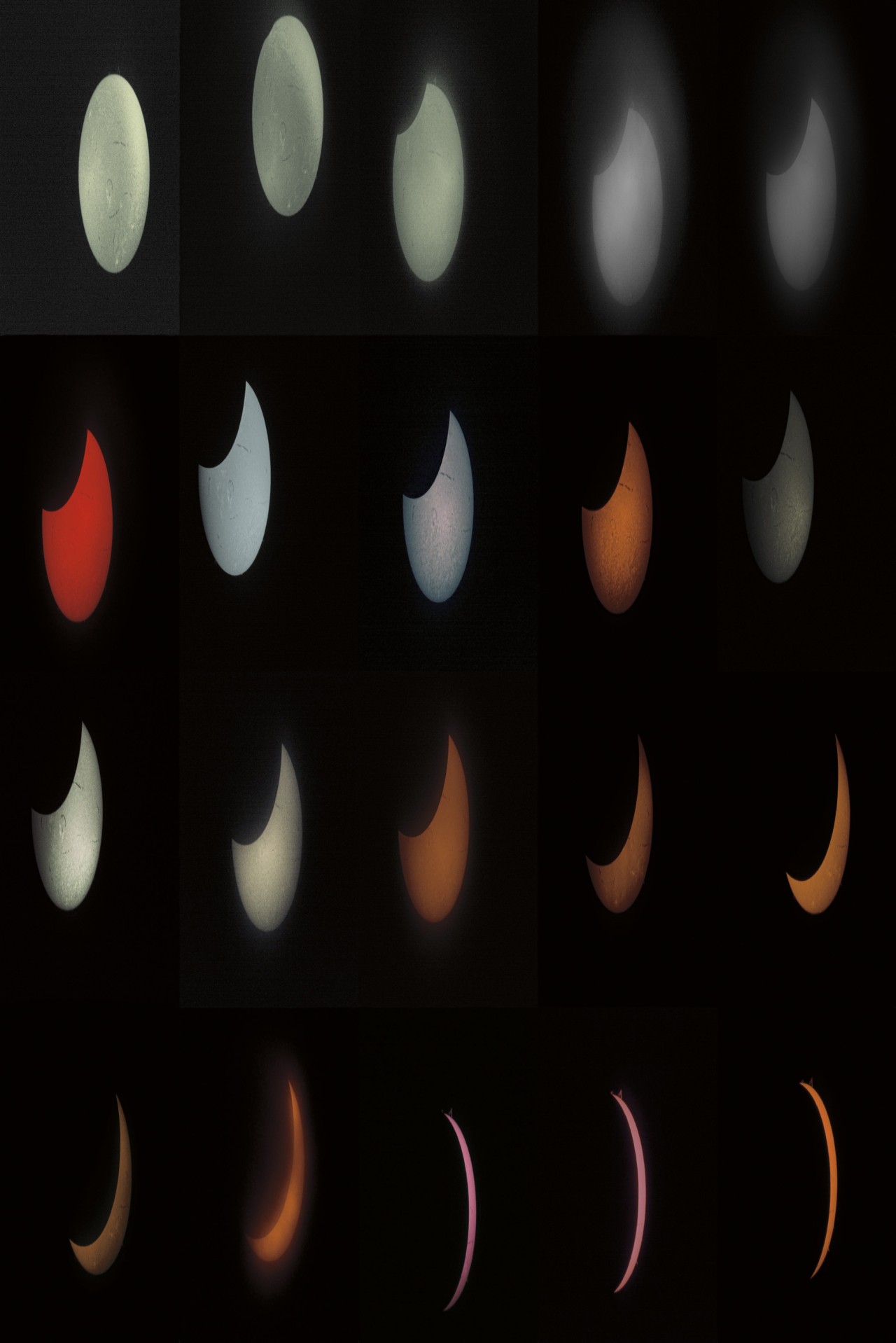

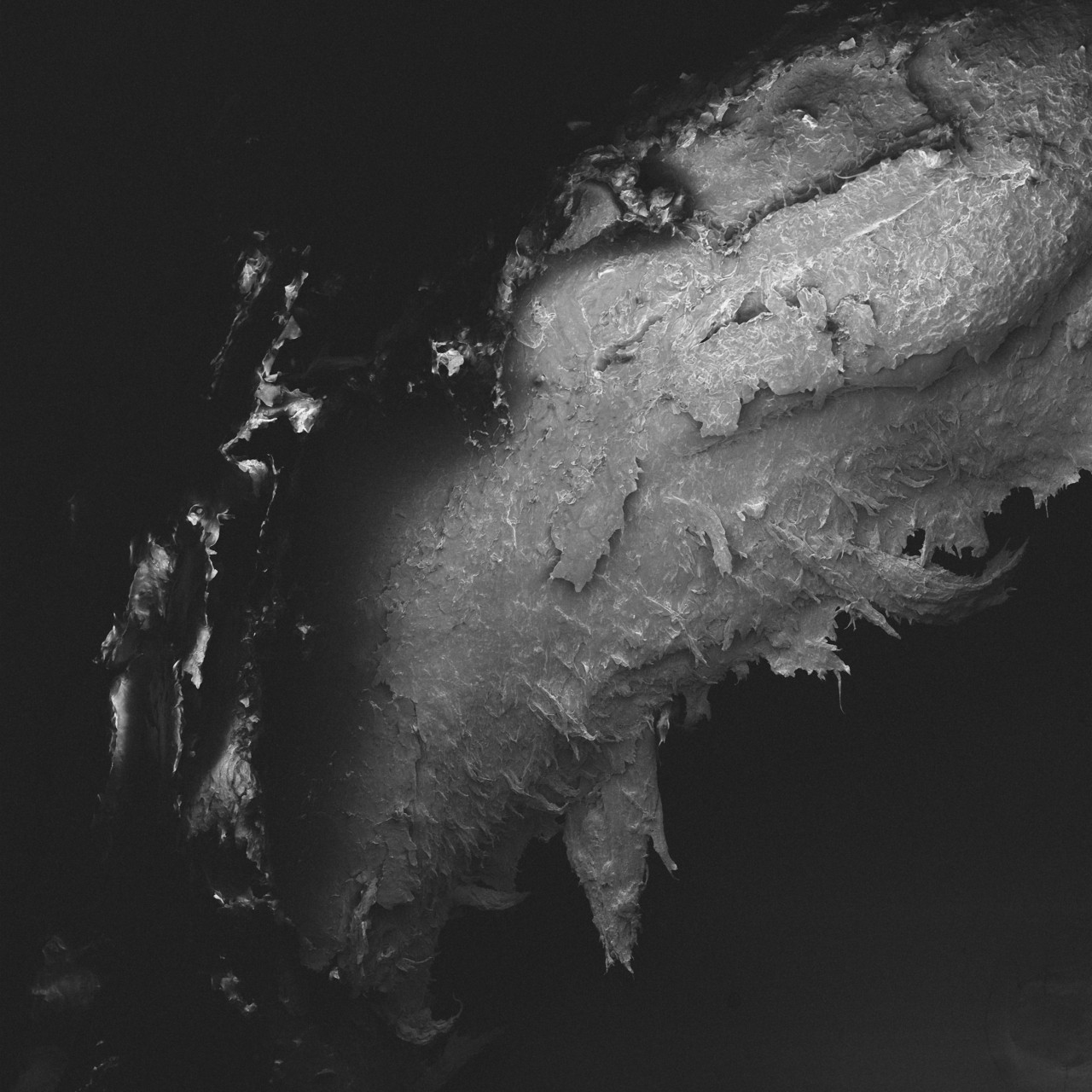

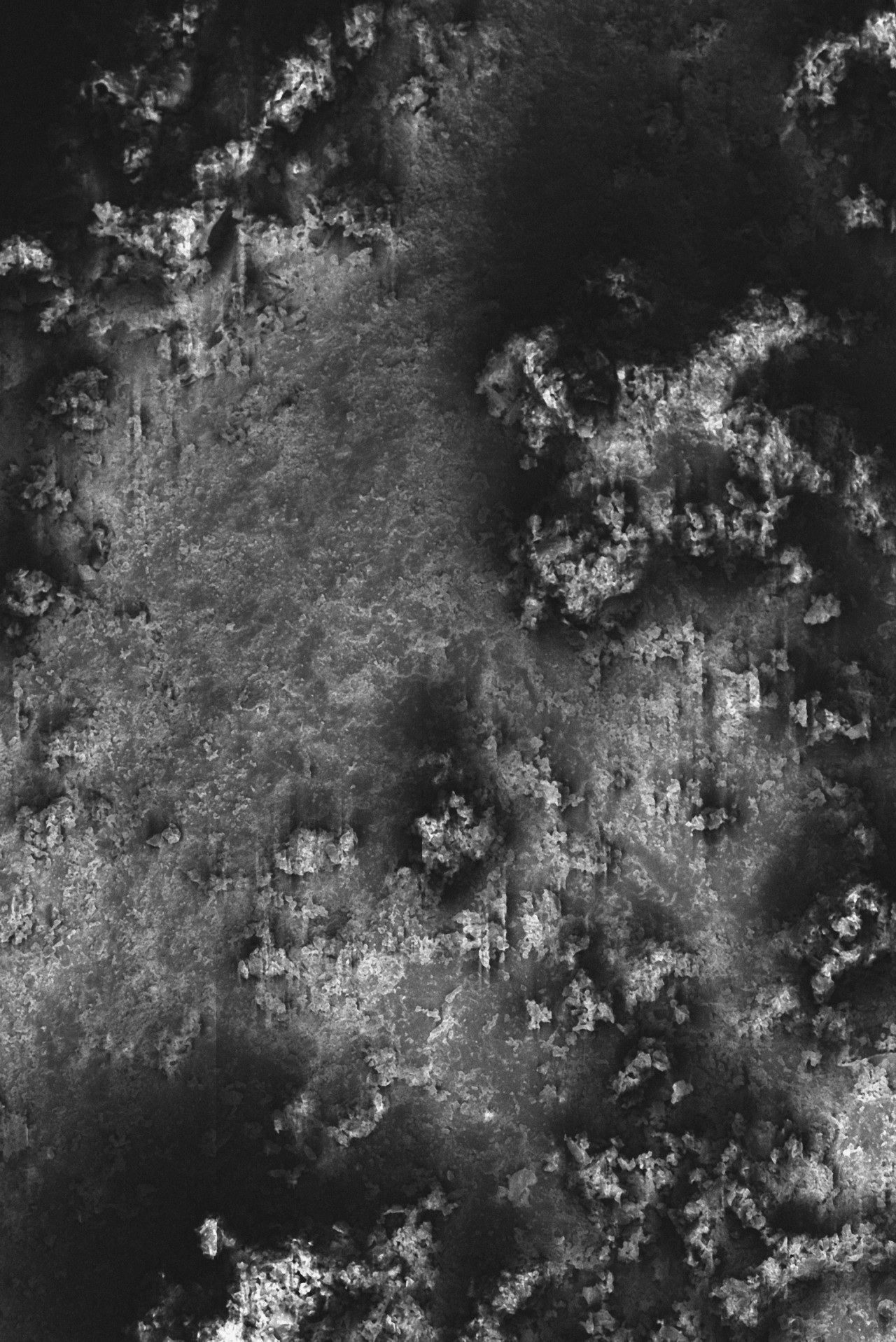

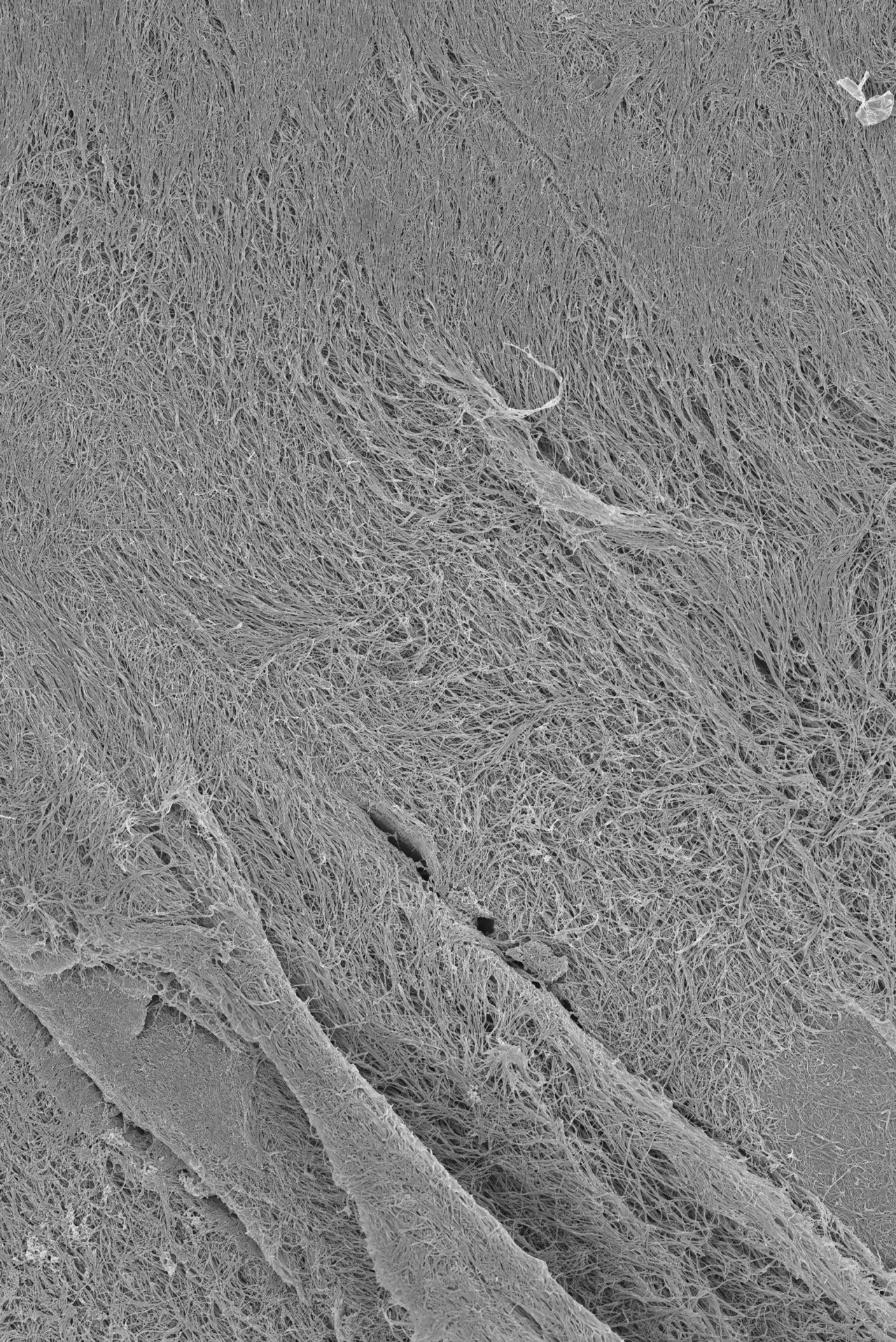

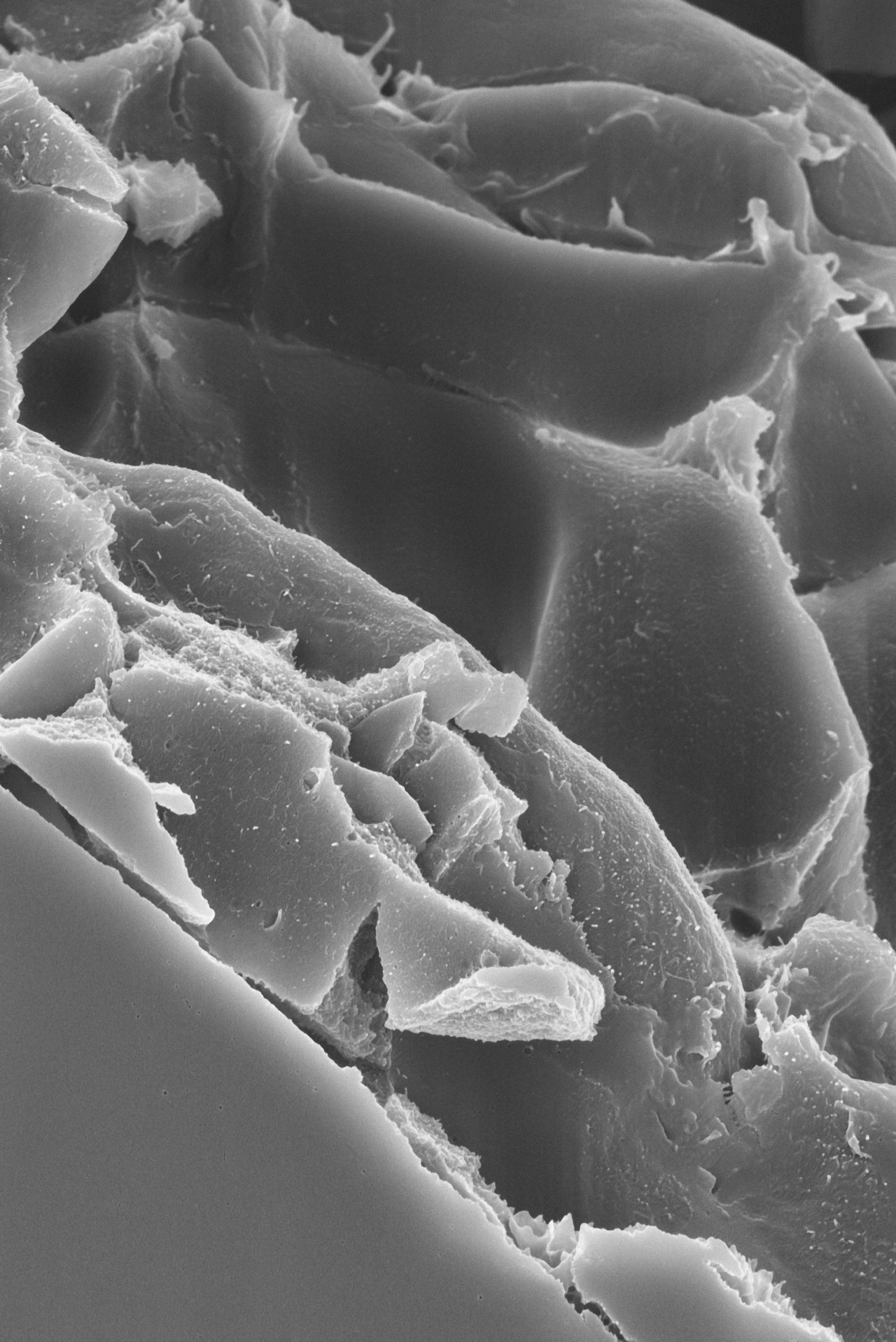

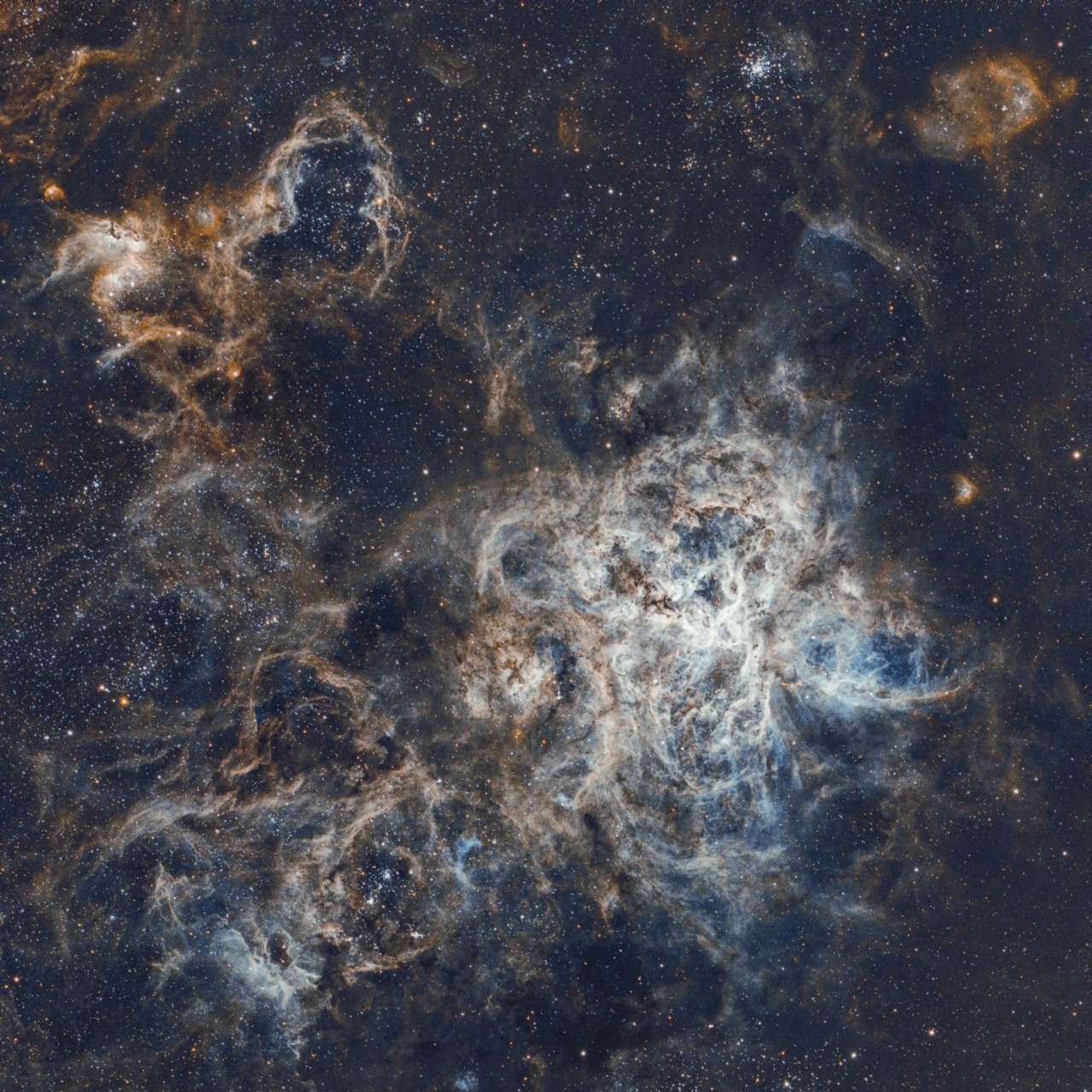

Photographer Michael Hauptman uses astrophotography cameras and an electron microscope to catalogue the vast scales of the universe, ranging from star-filled galaxies thousands of light years away to the microscopic cells that make up his own skin.

Words by Nick Martin

Photographs by Michael Hauptman

Faustin first sees a box. He doesn’t know what the box is, or what it does. His grandson, Amarasho, fiddles with metal rods on the roof. Suddenly, the box is full of snow. His daughter turns a knob. Now, the box is filled with a grainy wrestling match between Apache Red and a “Mericano.” Apache Red wins, to Faustin’s disappointment. Another turn of the knob, and the screen is filled with the crisp image of an Apollo mission’s Saturn V rocket. A countdown begins and ends. Smoke fills the box.

Then, fire.

Then, nothing.

These scenes come to us from the titular story in Men on the Moon, a short story collection from the esteemed Acoma Pueblo poet and writer Simon Ortiz. In a matter of two pages, Faustin, an Acoma grandfather, experiences the introduction of the television and the news of space travel, with Amarasho as his faithful, if at times playful, guide. As reality-altering as these bounds in technological progress would seem, Faustin handles them well, ever curious. He wants to know how the television works, why the wrestlers were fighting, when they’ll fight again, how to turn the television off—all practical inquiries. But it’s the moment when Faustin asks Amarasho why the men would go to the moon that I can’t stop thinking about.

“The men are looking for knowledge,” Amarosho tells Faustin.

Ortiz’s vision of how progress is framed to Faustin—and really, how it has been framed to his grandson—will ring familiar to the majority of people who still raise their head to the night sky for the sight of a harvest moon or a particularly starlit night. Space, for all the advances we’ve made in the past seven decades, is still a place that, conceptually, is easier to think of as there—distant from our own here. Many Indigenous communities have unique creation stories that intimately tie their spiritual and physical beings to the cosmos, and many others see no separation between earthly and celestial planes. Even so, space is a place that, among the many concerns that carry the average person through the hectic planet we currently inhabit, feels far enough away to fantasize about rather than think about in concrete terms of colonization and extraction. Haven’t we plenty of that here, in our own backyards?

The question of whether humanity deserves or has earned the right to be in space is secondary to the fact that we are already there, in force: government interests, commercial interests, research interests, private interests. In the latest count from astrophysicist Jonathan MacDowell, the Earth holds over 10,000 active satellites in its orbit, the majority of them low-orbit Starlink outfits. Give it more than 30 seconds of thought, and it’s easy enough to acknowledge that we’re closer to drill rigs on the moon and mining colonies on Mars than we’d care to admit. Yet, for the most part, save for the increasingly rampant Muskian intrusions in our collective consciousness, within most people exists a sense of hope, or at least the desire, to believe that what humanity is doing up in the heavens is generally for the betterment of our species. And so, like Amarosho, when we see astronauts video conference in from the I.S.S. on Good Morning America or catch a reel of the latest magisterial images from the Webb telescope, it is far easier to tell ourselves and those around us, “The men are looking for knowledge.”

The problem is, like Faustin, we know all too well what happens when they find it.

“Our past is not destined to be our future…we still have the opportunity to break this cycle of greed and reclaim the night sky.”

Space is arguably the most attractive place left to have the tired “Decolonize [Insert Literally Any Presently Colonized Arena]” conversation because space exploration still feels like a malleable concept. Human beings are in shuttles and space stations, and very soon we’ll be back on the moon, but we aren’t yet kicking back in condos on Mars. Still, Indigenous scholars and astronomers would encourage a different reading of how we apply the standards and stages of interplanetary colonization—that’s to say, humans aren’t on the precipice of colonizing space; we’ve already begun.

Space exploration has largely followed the blueprint set by the private, religious, and nation-led exploration of the world we currently inhabit. Space was explored, then it was militarized, and now the colonization stage is underway, with autonomous and semi-autonomous technology preceding the forthcoming floods of people. And this path of colonization, like the others, is being paved by way of carefully worded treaties.

The first and most significant of these agreements is the Outer Space Treaty of 1967, which has since been signed by all nations with space programs. The treaty outlawed the use of military bases and nuclear weapons in space and held that no country could claim partial or full ownership of a celestial body. This has been the governing accord that has guided space exploration for the past five-plus decades, and to its credit, we have not yet had all-out nuclear warfare in space, nor has the International Space Station been retrofitted into the latest strategically placed outpost for the U.S. military. But, as with the many other treaties, compacts, and legal provisions that were put in place over the course of the eighteenth, nineteenth, and twentieth centuries concerning the future of North American lands, waters, and resources, the Outer Space Treaty’s most important facets are not what’s on the page, but what’s missing.

The private and nationalistic forces that are currently driving space travel, satellite placement, and celestial exploration are competitive by design, not dissimilar to the European governments of centuries past eager to carve up North America, South America, Asia, and Africa. They want to be there first, they want to retrieve the most (be it knowledge, water, or platinum-grade metals), and they want the general population, or at least their shareholders, to celebrate them when they pull it off. And so the 1967 agreement is being updated, by way of the Artemis Accords.

There is plenty worth celebrating in the accords, which bear the name of NASA’s upcoming mission to send a new team of astronauts to the moon, just as there was plenty worth celebrating in the foundational Outer Space Treaty. But concerningly, the accords, like the preceding treaty they are deferential to, provide the political basis for private companies to extract resources from celestial bodies (namely the moon, asteroids, and Mars) and afford them the requisite protections for their equipment once in place. From section 10, titled “Space Resources”:

“The Signatories affirm that the extraction of space resources does not inherently constitute national appropriation under Article II of the Outer Space Treaty, and that contracts and other legal instruments relating to space resources should be consistent with that Treaty.”

This is the future. NASA and its global contemporaries, as well as the national bodies that oversee and fund these programs, have in large part decided that the rise of private, or commercial, space exploration and extraction will define the future of space travel. Rather than stand in the way of those corporate interests, they are opening the barn door. Like so many questionable policies, private space travel and exploration traces back to the Reagan administration’s many efforts at deregulation, specifically the Commercial Space Launch Act of 1984. Its contemporary legacy takes the form of bills like the SPACE Act of 2015, which in plain terms, gives private companies the go-ahead to “engage in the commercial exploration and exploitation of space resources.”

In two recent papers, Hilding Neilson, the Mi’kmaw astronomer and status member of the Qalipu Nation, drew a corollary between the basis for these latest accords and the extraction-fueled colonization and ecological decimation of North America. “Even if this does not mean ownership in outer space,” he wrote of the Artemis Accords in December, “it follows a path of the 19th-century Gold Rush where prospectors staked claims and took whatever was considered valuable while often leaving nothing but waste.”

To Neilson’s latter point, in addition to the extraction issue, the accords provide light guidance regarding the disposal of debris and discarded materials by these twenty-first-century prospectors. In addition to the 10,000 satellites in orbit, another 19,000 or so inactive pieces of technology, from out-of-service satellites to depleted rockets, already drift around Earth at rapid speed, destined to loop around our planet for hundreds of years. And in truth, the best way to contextualize the private companies itching for deregulation isn’t so much to compare them to prospectors as it is to think of them as Union Pacific or Standard Oil. As the industry barrels toward its projected 2040 valuation of a trillion dollars, the men standing at the front of the line are the wealthiest in the world.

If we stay the course, the next phase of colonization in space will circumnavigate the issues of militarization and extraction restrictions by way of privatization. Remember: No nation can lay claim to a slice of the moon or operate a military base. But a private U.S. company, primed to stick a drill rig on the lunar surface or position a team of “contractors” in an individually funded station or colony? According to the rules we’re writing now, that may soon be fair game.

Men on the Moon, by way of a monstrous dream had by Faustin, asks us to question what experience and wisdom can tell us when we’re being sold a purportedly blind pursuit of knowledge.

For instance, we know through both historical and contemporary examples that the governing and ruling forces of the world today—particularly but not exclusively those born out of the tradition of colonization—view the moon, the asteroids, and Mars as places to conquer, the same as the private companies itching to set up shop. Yes, the Outer Space Treaty forbids the formal claiming of celestial lands—so too did many other legally ratified treaties here on Earth. To update a sentiment from the ignominious president Andrew Jackson: The U.N. has created its space treaty; let’s see it enforce it.

The question is, how do we stop history from repeating itself? How do we stop our species from barreling toward a reality in which we doom this planet to climate hell, then create lunar and martian colonies while dredging those new homes for all they’re worth until we’re forced to again depart and look elsewhere? That is the most dismal and Interstellar vision of the future, but truthfully, it can also feel the most realistic, because it’s the path defined by greed, sold to the public as the pursuit of knowledge. And we have seen greed win out so many times.

Thankfully, there are Indigenous voices in the world to remind us that our past is not destined to be our future—that we still have the opportunity to break this cycle of greed and reclaim the night sky.

“It is essential to recognize that assuming space colonization is an inevitability disregards the concerns of the majority of Earth’s population,” wrote Karlie Alinta Noon, a Ph.D. astrophysics candidate from the Gamilaroi Nation in Australia, in a 2024 paper for the think tank Centre for International Governance Innovation. “Rather than forging ahead with discussions solely driven by the interests of financial and political elites, an implementation of space law that foregrounds inclusivity, ethics and the reimagining of human activities must be prioritized.”

What this reimagining functionally looks like is much like the reimagining of rights for natural beings here on Earth. As rivers and lakes and lands have steadily gained legal protections and living entities, Nielsen makes the case in one of his papers that we should extend this line of thinking to space. “The Moon and Mars and other Solar Systems objects have their own rights to exist and be,” he wrote, noting that an Indigenous-led or informed framework of space interaction would involve constantly humbling ourselves and resisting any assumption that we have a right to “explore” these places. That does not outright preclude humanity from engaging in mining activities or building moon condos, but it also does not automatically grant us this right. Instead, this framework would remove the veil we’ve cast between here and there. Land and space would be viewed as part of a single continuum, all of it deserving of a healthy, relationship-centered interaction.

Valmaine Toki (Maori), who sits as a Professor of Law at the University of Waikato and served two terms as an independent expert to the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues, is another figure whose leadership reminds us we have, in some capacity, already built the mechanisms to engage in this healthier version of space law and interaction.

For all the critiques to be offered of the existing treaties and agreements that allow for this greed to flourish, there are provisions within them that can provide Indigenous nations and viewpoints a true voice and work toward breaking that cycle. One such mechanism is the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP).

While UNDRIP is still yet to be domestically adopted by the full list of national signatories, Toki wrote in 2021 that the document’s list of protections and rights “extends to land and territories within the celestial or non-earthly realm.” And the rights guaranteed to Indigenous nations in UNDRIP would extend to the Artemis Accords, as they defer often to principles established in the Outer Space Treaty, which states in clear terms that the signatories of the treaty “shall carry on activities in the exploration and use of outer space, including the moon and other celestial bodies, in accordance with international law, including the Charter of the United Nations.”

The point here is not to use UNDRIP to halt space exploration, or to argue that private entities shouldn’t ever be operating in space. Rather, it is to engage a significant and ideologically diverse swath of the world to help us better understand the alternative ways we could be thinking about space exploration.

By engaging Indigenous nations and communities and allowing them a more distinct and defined role in determining how we move forward with our relationship to space and all that it contains, the world might find that between the binary of space conservation and space exploitation exists a true alternative, based in reciprocity.

There’s still time to change our guiding ethos—to alter our course, both here and there.

“How do we stop our species from barreling toward a reality in which we doom this planet to climate hell, then create lunar and martian colonies while dredging those new homes for all they’re worth until we’re forced to again depart and look elsewhere?”

Special Thanks Kym Thalassoudis and Steve Kelly

In order of appearance: Large Magellanic Cloud, Heart Nebula, human skin, meteorite, Coalsack Nebula, tardigrade claw, Large Magellanic Cloud, solar eclipse, Tarantula Nebula, cow cartilage, human blood, telescope, tardigrade, layers of clouds, a day moon, a moon setting in Australia, and a solar eclipse.

We would like to acknowledge the use of the Scanning Electron Microscope at Columbia University, and to thank the Columbia Nano Initiative and Dr. Amir Zangiabadi for their assistance with sample preparation and imaging.

This article first appeared in Atmos Volume 11: Micro/Macro with the headline “Written in the Stars.”

Written In the Stars: Imagining a More Ethical Space Travel