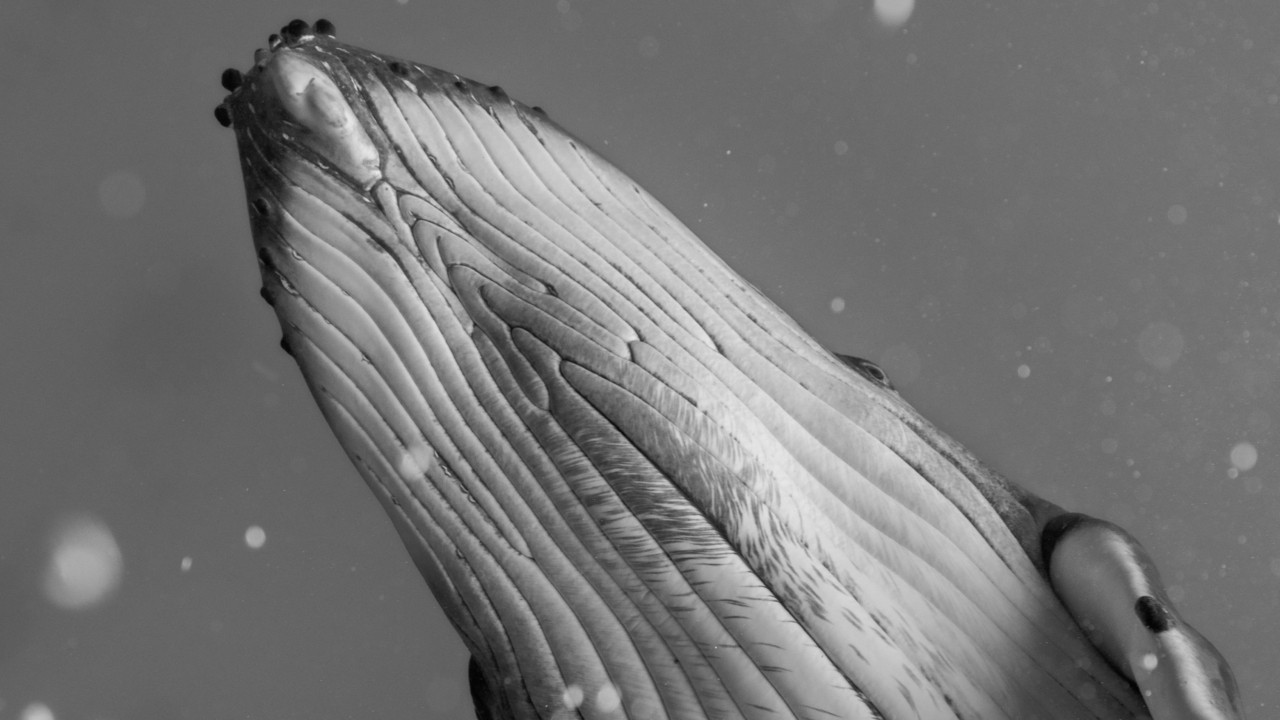

Photograph by Nessim Stevenson / Kogia

words By Rachel Ramirez

Across every tale passed down through Tongan generations, one remains unchanged: the Polynesian kingdom’s creation story. The beginning was the ocean; and from the ocean, the islands’ first ancestors emerged.

In one creation story, there were two ancestors: Limu, the seaweed, and Kele, the sea sediment or sea mud. Limu and Kele lived in the ancestral land of Pulotu. They gave rise to a rock called Touia’o Futuna, which produced four sets of twins who gave birth to the ancestors of Tonga’s most important deities, including Maui, the god who hauled some of Tonga’s coral islands out of the ocean with his famous fishhook.

Among Touia’o Futuna’s sacred descendants, said Tēvita Ka’ili, a Tongan professor of anthropology and cultural sustainability at Brigham Young University in Hawai’i, are the magnificent creatures that continue to swim and sing around Tongan waters today: whales.

In much of the South Pacific, these creatures are seen as deities, ancestors, and relatives. There is even an ancient ritual in which Tongans, when they encounter a whale during their sea voyages, would offer a cup of kava—a traditional drink made from the Piper methysticum plant root—to the whale as a sign of respect, said Ka’ili, who has been studying how creation stories inform people’s relationship to nature.

But whale populations have declined over the last few decades due to increasing threats of the climate crisis, unsustainable fishing practices, ship strikes, habitat degradation, and pollution.

These harms so threaten the island nation’s ancestral history and existence that in June, Tongan Princess Angelika Lātūfuipeka Tukuʻaho called for doubling down on their protection at the United Nations Ocean Conference in Nice, France. Speaking to international leaders and attendees, the princess called for the recognition of whales as legal persons, suggesting the Kingdom of Tonga would appoint human guardians to represent the marine mammals in court.

As Tonga prepares for general elections in November, whale and ocean advocates have been working on a national bill called “Te Mana o te Tohorā,” or “Authority of the Whale”: legal personhood framework to present to the new government. This draft legislation, set to be introduced to Parliament, seeks to grant whales fundamental and legal human rights to exist, thrive, and be healthy.

“The time has come to recognize whales not merely as resources but as sentient beings with inherent rights,” Lātūfuipeka Tukuʻaho said. “Their survival demands a transformative shift in our legal and ethical relationship with the ocean.”

Legal personhood isn’t a novel concept. It’s been sought for non-human entities like corporations, universities, and churches to have rights, responsibilities, and the ability to interact with the legal system. This allows them to sue or be sued, enter into contracts, or limit the liability of shareholders. A similar concept has also been sought to grant full legal personhood to a fetus or embryo, a contentious topic primarily debated in the United States that would support the prohibition of abortion.

In the Rights of Nature movement, assigning legal personhood to Mother Earth’s natural features means protecting them from environmental degradation. In New Zealand, for example, the country recognized the Whanganui River in 2017 and Mount Taranaki early this year as legal persons, granting them rights and legal standing to protect their sacred connection to the Indigenous Māori people.

It’s also been used for non-human animals, recognizing their cognitive and emotional capacities. Advocates believe legal personhood is critical to provide safeguards against animal cruelty and exploitation, particularly in areas like laboratory research. Other countries like Panama and Ecuador have similar laws.

“There’s really just no way for animals to assert their own rights unless they are deemed to have personhood, such that they have legal standing to sue in their own names,” said Caitlin Hawks, chief programs officer with the Animal Legal Defense Fund.

Teeming with life, the vast Pacific Ocean is home to tens of millions of people living on small islands as well as a staggering array of marine biodiversity, including more than half the world’s whale species. Traveling from the frigid Antarctic waters to the tropical, life-giving waters of Tonga, where whales gather to mate and give birth, the animals carry a constant, deep song throughout their ancient, increasingly perilous, migratory journey.

In June, the princess, alongside Pacific whale conservationists and advocates, launched the Moananui Sanctuary Agreement, a regional commitment and framework grounded in the Rights of Nature movement for ocean conservation. The Indigenous-led initiative proposes to create a vast, connected network of marine protected areas across the Pacific, spanning 12.5 million square kilometers (about 4.5 million square miles). Doing so would protect the migratory corridors of whales, ensuring their long-term survival as well as the health of the oceans.

The Moananui Sanctuary regional agreement set off the adoption of the national-level Te Mana o te Tohorā draft legislation, which is set to be introduced to Parliament, seeking to grant whales fundamental and legal human rights. Ka’ili, the professor from Brigham Young University in Hawai’i, said this initiative presents a perfect way of marrying Western laws with Polynesian cosmology.

“One of the things that comes out of our Pacific culture is that we are guardians of this marine life. We are guardians of whales as whales are also guardians of us,” Ka’ili said. “Using Western laws such as legal personhood allows us to continue this work of being a guardian to them and to make sure their voices are represented within the legal arena and so forth. It is a way to be able to bring that voice into a setting that is recognized.”

“The time has come to recognize whales not merely as resources but as sentient beings with inherent rights. Their survival demands a transformative shift in our legal and ethical relationship with the ocean.”

Michelle Bender, head of ocean rights at Ocean Vision Legal and one of the lawyers working on the draft legislation with law firm Simmons & Simmons, said the bill would create a whale guardianship council, comprised of representatives from Indigenous and local communities as well as government, which would guide the management and regulation-making to protect whales. The council, she said, is intended to be the human face for whales “to present and ensure their interest, intrinsic value, and rights are represented in all decisions affecting their health.”

Another aspect of the bill, Bender added, involves how to navigate environmental impact assessments. “Right now, you can argue that (these assessments) are very much there to support and facilitate development rather than to ensure the protection of the environment,” Bender said. “The idea of what is significant harm is just a value statement and very much dictated by human interest and economic interests at the moment, so we’re changing that within the context of the whale legal personhood effort.”

The Moananui Sanctuary agreement and the draft legislation from Tonga build on a landmark treaty that Takoko, alongside Māori tribes and other Indigenous leaders across the Pacific, helped craft and sign last year. Led by the late Māori King Tūheitia Potatau Te Wherowhero VII, the He Whakaputanga Moana, or Declaration for the Ocean, while legally non-binding, recognizes whales as legal persons, allowing them the right to freedom of movement, a healthy environment, and the ability to thrive alongside humans.

Princess Lātūfuipeka Tukuʻaho builds on a royal legacy with this initiative. In 1978, the late King Tāufa’āhau Tupou IV, her grandfather, issued a Royal Decree banning all whale hunting in Tongan waters, creating one of the planet’s first sanctuaries. At the time, whales in Oceania were hunted by “Yankee”-style whaling vessels, which escalated during the 20th century as factory ships and other ocean operations advanced technologically.

“In recognizing whales as legal persons, what that is doing is shifting how we interact with and value whales,” said Bender. “So it shifts this perspective of whales and the environment as a resource and property to exploit with a value primarily derived from human benefit and utility towards recognizing that whales have intrinsic value.”

Bender has been working with the Rights of Nature movement for almost a decade now, including work on a similar initiative recognizing legal rights for Southern Resident Orcas in the Salish Sea in the Pacific Northwest. So when she met Mere Takoko, co-founder of the Pacific Whale Fund and one of the main architects of the bill, in 2023 during Climate Week NYC, they knew their visions aligned. In 2022, Takoko established the Hinemoana Halo Ocean Initiative, named in honor of the Māori goddess of the ocean, to create “a shield against the threats that endanger their very existence,” she wrote previously for Atmos.

Protecting whales isn’t just for the people of Oceania. Each great whale stores 33 tons of planet-warming carbon over its lifetime, on average (a typical gas-powered car in the US emits roughly five tons of carbon per year). When it dies, the whale carries this locked carbon with it to the ocean depths far away from the atmosphere. Whale poops are also critical carbon sinks: Rich in nutrients, whale feces are taken up by phytoplankton—tiny organisms that are the foundation of all marine food webs and the reason for every breath humans take every few seconds.

One of the biggest pressure points for whales is the climate crisis, said Rochelle Constantine, a marine biologist at the University of Auckland in New Zealand. “We know that in Oceania, the water will become too warm for the whales,“ she said. While whales can find habitat outside that Pacific Ocean region, the “strong cultural connection that many Pacific peoples have to humpback whales may be compromised.”

Ocean conservation advocates saw a major win in September: More than 75 countries ratified the “high seas treaty,” a groundbreaking international agreement to protect marine life in the ocean beyond national borders, also known as the high seas, which cover nearly two-thirds of the world’s ocean.

Tonga has yet to ratify the agreement—and with the elections looming and an effort to recognize whales as legal persons on the horizon, many are watching closely.

Tonga Could Soon Become the First Country to Recognize Whale Rights