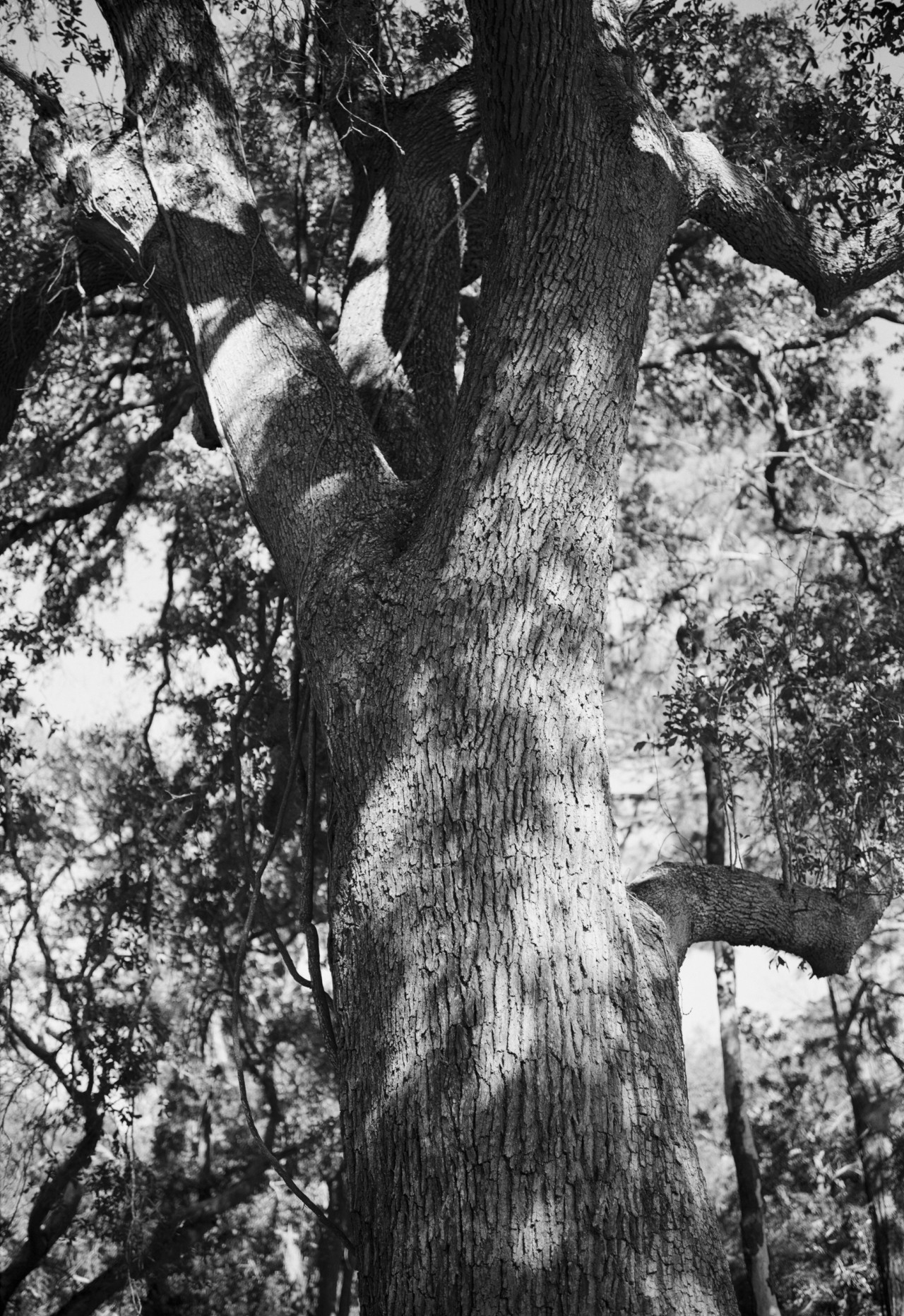

These photographs, shot by Rahim Fortune, document several Black Heritage trees that have been mapped across Texas. This lone tree stands on the Varner-Hogg plantation in West Columbia, Texas.

Words by Jasmine Hardy

photographs by rahim fortune

On the island of St. Croix, the largest of the U.S. Virgin Islands, a nearly 300-year-old baobab tree stands firmly in the center of a grass field. Its 50-foot-wide, swollen trunk and winnowy branches are a spectacle among an otherwise ordinary backdrop. Onlookers say it looks as though the tree was planted upside down. That’s why it’s been nicknamed the “Walking Tree,” drawn from an ancient legend that God inverted it to keep it from wandering.

Native to Africa, the baobab is not meant to grow here. How it arrived in the Caribbean around 1750 has long been the subject of speculation. But for many islanders, the answer is clear: by way of the transatlantic slave voyage, or Middle Passage. “The enslaved people [brought] the seed in their hair, necklaces, and earrings,” said Olasee Davis, a Caribbean ecologist and historian. “That is how the seed came to this part of the world.”

Stories of how the baobab arrived, and what the tree has come to mean, are commonplace and handed down through generations. Growing up on St. Croix, Davis and the other children were often told of the tree’s historical and spiritual significance—even that its hollow trunk could serve as a portal to home. “We were told that if we went to the baobab when the moon was full, the hole would open up and we could go back to Africa,” Davis recalled.

With a life span that can exceed 1,000 years, baobabs are often described as witnesses to history. This one is officially known as the Grove Place Baobab, and has been a landmark of Black history and a keeper of inhabitants’ tales for centuries. In its relatively brief three centuries on St. Croix, it has already witnessed and endured slavery under Danish colonial rule, the Emancipation Rebellion of 1848, and the decimating winds of Hurricane Hugo in 1989, to name a few.

“When you see the tree, history comes alive,” said Davis.

The Grove Place Baobab tree is just one of more than 100 others spanning the African diaspora that have been identified as Black Heritage Trees for their roles as living witnesses to pivotal moments in Black history. Led by archaeologist and National Geographic Explorer Alicia Odewale, the Black Heritage Tree Project is now mapping these trees in efforts to protect them and the knowledge they carry.

For Odewale, traditional archaeology has only told half the story of humanity. Trees, she argues, reveal the rest.

“We started the Black Heritage Tree Project as a way to allow the trees to take center stage with the storytelling, and reconnect the African diaspora through the trees that we’ve been connected to for generations,” Odewale said. “Somewhere along the way, we lost that connection.”

Odewale began the project in her hometown of Tulsa, Oklahoma, where the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre still shadows the city’s name. During her first archaeological survey there, she followed the trees. As their roots expanded underground, a row of hackberries pushed fragments of the past to the surface, among them bottle fragments and bits of bricks and mortar. The artifacts formed a kind of puzzle for Odewale to fit together.

The trees themselves were too young to have stood during the massacre. But their thick, darkened bark—a natural adaptation that offers a form of fire protection—revealed them to be descendants of the trees that had endured the flames. “It reminded me of how people in my community behave as descendants,” Odewale said. “We grow as if we carry this history with us; as if we are still marked by it.”

The parallels between trees and humans are deeply intertwined. Like people, trees speak to one another, share stories and nourishment among their communities, and pass down wisdom and warnings to their offspring. The exchange between the distinct organisms is constant: We breathe what trees exhale; they, in turn, depend on what we release. Survival is mutually dependent. It is hardly surprising, then, that when one is afflicted, suffering trails closely behind for the other.

Do poplar trees still carry the weight of the human bodies that once hung from their branches? Do Southern magnolias, contorted and gnarled by age, hold memories of bloodshed in their roots?

In South Carolina, there are stories of the 500-year-old Angel Oak with an air so heavy that it is suspected to be surrounded by spirits of enslaved Africans, the despair of a generation soaked in its drooping Spanish moss. Stories like these are folklore—but science confirms that these trees are not passive bystanders to history. They’ve physically suffered by proxy: Plantations across the United States created a monocrop culture so pervasive that it depleted soil diversity, altered water systems, and triggered long-term ecological decline. Acres of land were cleared for cotton and sugarcane. And trees no longer stood to witness to the sins of human kin, for better or for worse.

“Do poplar trees still carry the weight of the human bodies that once hung from their branches? Do Southern magnolias, contorted and gnarled by age, hold memories of bloodshed in their roots?”

But for Odewale, the Black Heritage Tree Project is not solely about cataloging histories of harm. “The ways that we connect to these trees are endless,” she said. “It’s never just about the torture that’s been done to them and to us. It’s the connection that’s been happening both through joy and pain in a cycle.”

One such tree is the Greenwood Legacy Tree in Tulsa, once referred to as the Tulsa Race Massacre Tree. The American elm bends almost 90 degrees, its trunk nearly parallel to the ground, but its branches reach upward: skybound. The tree hangs on like a stubborn elder with too much wisdom to spread, living proof of a history that’s time and again been a target for erasure. It survived not only the attempted burning down of a thriving Black Tulsa in 1921, but also the rebuilding of a city from the ashes.

The Black Heritage Tree Project has documented dozens of trees associated with creative resilience: live oaks carved with symbols that guided people along the Underground Railroad; baobabs whose hollow trunks became burial sites; kapok trees whose leaves were used as medicine by the enslaved—or, in some accounts, as poison for enslavers; sycamores whose broken limbs were tied together as a sign of matrimony; and mahogany trees that stood as windbreaks along Caribbean shores.

Odewale’s favorite trees are the freedom trees. “This is the spot where [the ancestors] stood and heard that freedom had come,” she said. “I could actually touch this tree that they touched and try to imagine what they were feeling at that moment.”

Texas, which has the most trees documented in the project, is dense with stories of liberation. In Houston, home to several former freedmen’s towns, a 200-year-old live oak marks the place where some of the last enslaved Africans were told they were free: a day eventually commemorated as Juneteenth. Now known as The Freedom Tree, it has become a pillar in the community and a space for remembrance.

“[The trees] were always there, whether we noticed them or not,” said Naomi Harris, the Houston lead for the Black Heritage Tree Project. “They were there, and they were witnessing our history.”

Nearby stands what enslaved men, women, and children called The Can’t See Tree, on the grounds of the Varner-Hogg plantation. According to Harris, its broad canopy once shielded enslaved laborers from overseers during sugar harvests, providing a momentary break from persecution that doubled as a quiet act of resistance behind the tree’s mossy covering.

“If that doesn’t inspire you, I don’t know what can, because we were not taught our history,” said Harris. “We were told a lot of stuff, but we were not always told the truth because it was violent, it was bloody, and it was painful. But it is also beautiful.”

For plant scientist Beronda Montgomery, this relationship with trees is ancestral—and the growing distance from it, she argues, can be attributed to the trauma of chattel slavery. In her newly released book, When Trees Testify, Montgomery traces how Black botanical knowledge was once valued and exploited. Enslaved people with expertise in cultivation and plant medicine were actively sought after.

Montgomery now asks: How might that ancestral connection be reclaimed? How do we honor the ancestors, and the trees that sustained them? As a longtime researcher of photosynthetic organisms, Montgomery commonly describes the process as a sacred exchange of breath between beings.

“[The trees] were always there, whether we noticed them or not. They were there, and they were witnessing our history.”

Today, with more than one-third of trees at risk of extinction, Montgomery and the leaders of the Black Heritage Tree project face the daunting task of keeping trees, and the multitudes they hold, from vanishing.

“Every time I go somewhere and see these old trees, my first response is, whose breath is captured in this tree?” she said. “What do I know about them? How do I honor their memory? I know my breath can be captured by a tree that will live hundreds of years from now. Am I living a life and taking actions that are worthy of that?”

In the American South, elders often say: If these trees could speak. Montgomery suggests they already do. “They can testify to the wholeness of our existence,” she said. “That’s the good and the bad—all of the experiences that make us who we are.”

The Trees That Bear Witness to Black History