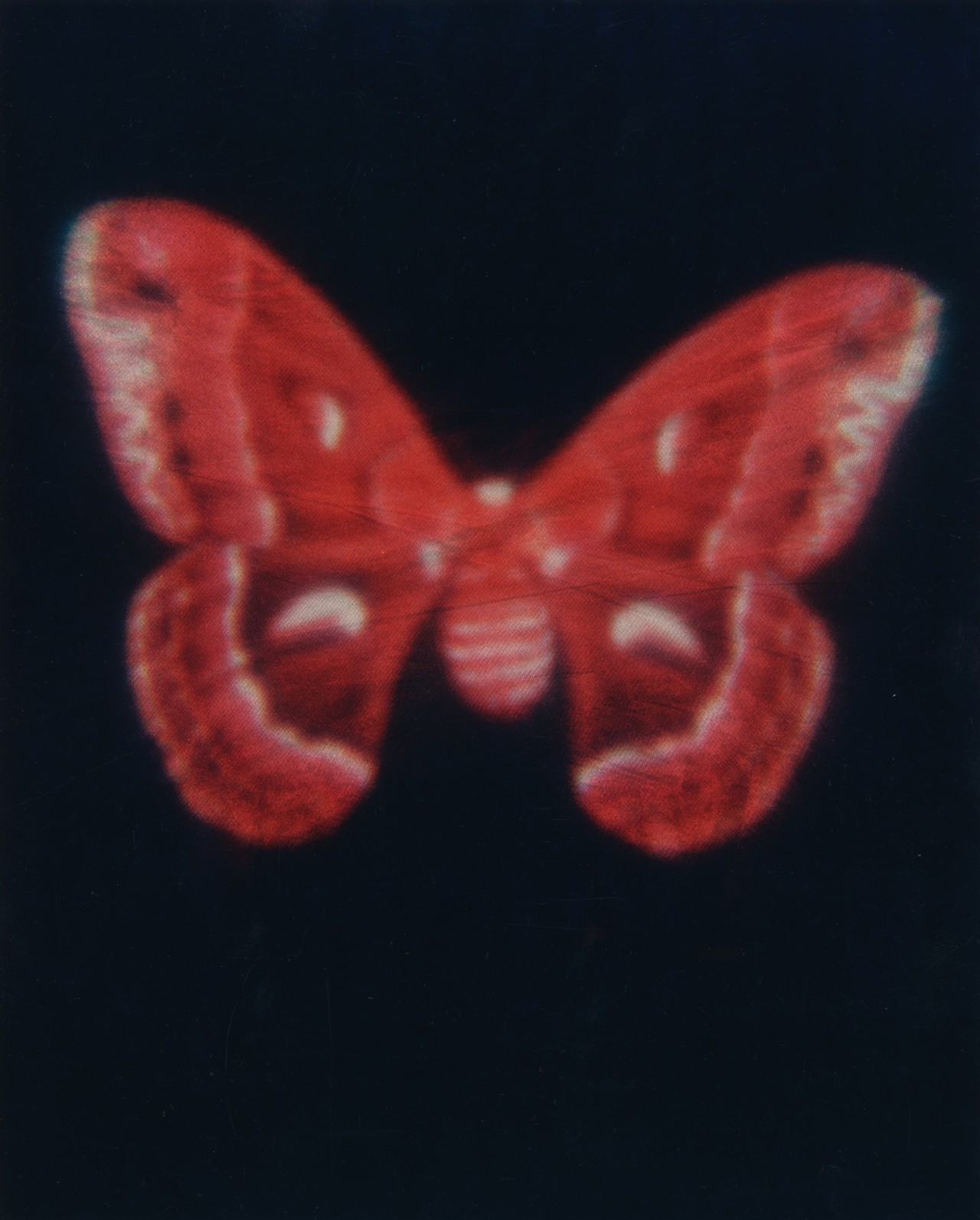

Photograph by Carter Smith / Trunk Archive

words by willow defebaugh

“The desire of the moth for the star,

Of the night for the morrow,

The devotion to something afar

From the sphere of our sorrow.”

By now, my admiration for insects—with their dazzling displays of metamorphosis, alien-like adaptations, and symbiotic behavior—should by no means be a secret. And while I have written many an ode to the sublime beauty of the butterfly, the scales of its often overlooked and shadowy counterpart, the moth, are dusted with as much wisdom for us to behold. Especially when it comes to desire: like a moth to a flame, so the saying goes.

Moths are a sprawling group of nearly 160,000 species of mainly nocturnal flying insects of the order Lepidoptera. While less ostentatious and widely beloved than the brightly-colored butterfly, moths are equally evocative of the beauty of transformation. They, too, undergo complete metamorphosis, radically altering their morphology in the pupa phase. But where butterflies grow a hard outer shell called a chrysalis, moths spin a cocoon of silk, even incorporating elements of their environment such as leaves. Transformation can be soft, too.

Without moths, there would be no butterflies. They have flitted about the Earth for at least 200 million years. It wasn’t until around 100 million years ago that a subset of these nightbound beings sought the light of the Sun, eventually evolving into butterflies. This leap was once thought to be due to the infamous battle between bats and moths, but bats didn’t appear until 50 million years ago. It turns out, these moths desired new food sources: the nectar of freshly minted species of flowering plants. They were dreamers, drawn to a different world.

The moths that remained in the dark play a crucial role in their ecosystems. They are nature’s nighttime gardeners, pollinating plants that flower by moonlight (one study found that they pollinate even more flowers than daytime bees, which are known as super-pollinators). This relationship has given rise to some extraordinary examples of symbiosis, such as between yucca moths and Joshua trees. Each Joshua tree requires a specific yucca moth to pollinate it, not offering nectar as a reward, but shelter for its kin. Even in darkness, reciprocity can bloom.

Out of all the lore surrounding moths, perhaps the most widely misunderstood is their attraction to light. Until recently, the leading theory for this behavior was that it has to do with the way they travel by celestial bodies, navigating the night by positioning themselves in relation to the Moon and stars. This method, known as transverse orientation, is then disrupted by other light sources, luring the moths to their ethereal glow—and sometimes, demise.

Research published in Nature Communications earlier this year suggests a more complex truth; rather than being drawn to the light, moths become “trapped” by it. In a series of experiments, scientists observed moths flying around artificial light sources with their backs to them, even upside down, in endless loops. Rather than flying toward the light, they deduced that moths always fly with their backs to the brightest source—an evolutionary gift that lets them tell up from down while traversing the dark.

Perhaps it is time we liberate the moth; once the subject of a parable about the destructive nature of desire, it was never really trying to fly into the flame. Desire can be healthy; it can drive us toward personal and collective transformation, dreaming new ways into being. It is the work of a lifetime to learn, though, how to navigate a world of artificial illuminations that tries to capitalize on our desires—to trust and discover for ourselves which way is up.

To a Flame