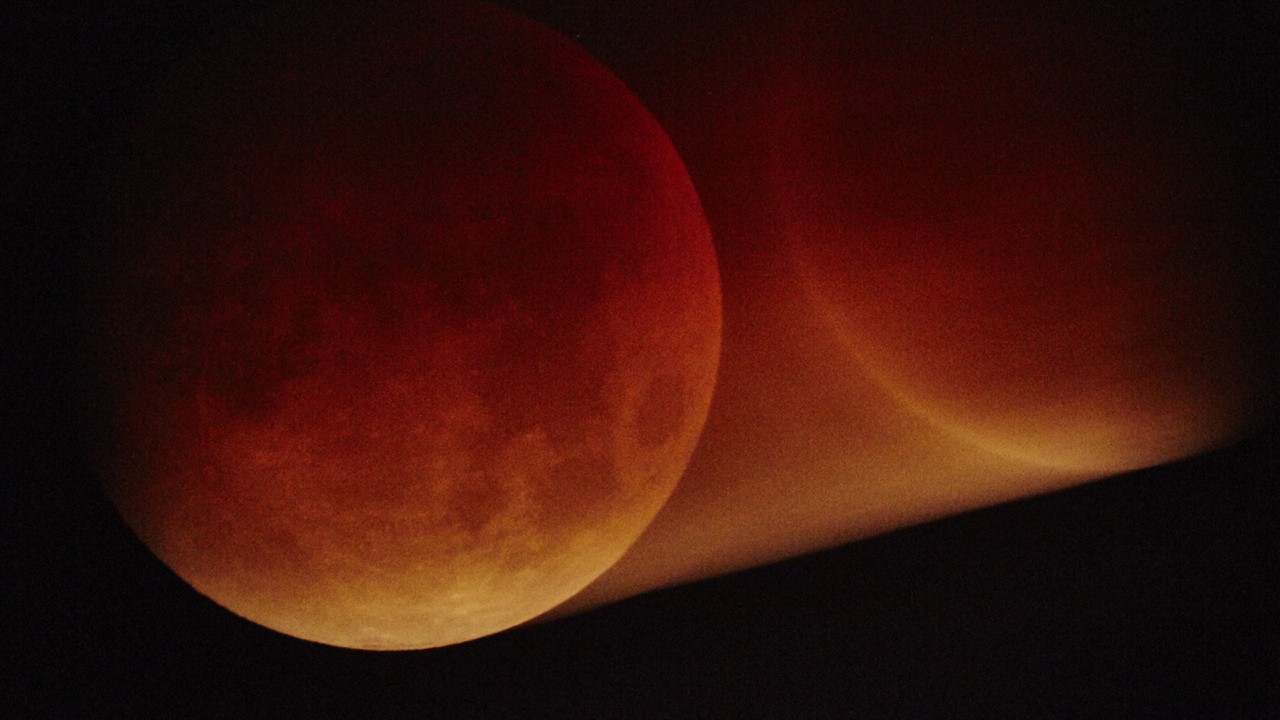

Photograph by Josh Shinner / Kintzing

words by willow defebaugh

“The problem with all words is that they are sticks—they can never be the moon.”

—Abdi Assadi

In Shadows on the Path, a book about the pitfalls of attempting to live a spiritual life, Abdi Assadi warns of the perils of putting people on pedestals. We live in a world that worships celebrities, elevates teachers as gurus, and expects our political leaders to have all the answers. Assadi observes that when a person reveals important truths to us or helps us grow, it’s easy to confuse that person for the Moon—rather than see them as a stick that pointed us toward it.

Before I circle back to that metaphor, allow me to orbit for a moment. On Earth, we only have one moon. The leading theory for how it formed is that some 4.5 billion years ago, a celestial body the size of Mars collided with our planet. The debris that scattered into space—made of both the Earth and this stranger from space—accumulated in our atmosphere. It was forged into a sea of magma and then crystalized over 100 million years. And so, the Moon was born of chaos.

The Moon engages in a celestial waltz known as synchronous rotation; it rotates at the same rate that it orbits the Earth (which takes about 27 days, though we see it as 29 due to our own planet’s rotation). This means that the same side of the Moon is always facing us, which birthed the idea of the “dark side of the Moon”—a misnomer, considering the face we do see is often cast in shadow and the other hemisphere still receives the Sun’s rays. Illumination can be illusory.

Just as the Earth does, the Moon gets varying amounts of sunlight throughout this cycle, creating its own days and nights: two weeks each, given its monthly rotation compared to our 24-hour one. As a luminary, the Moon is a lightbringer—though really, moonlight is sunlight reflected off its surface. Our planet does the same, casting off earthlight (or earthshine). In fact, on a slim crescent moon, it’s earthlight that lets you sometimes see the shadowed part of the Moon.

These shifting illuminations are what we call lunar phases. On full moons, the face we see is fully lit up by the Sun; on new moons, the other hemisphere faces the Sun, so the one we see is cast in shadow. Eclipses occur when the Earth, Sun, and Moon perfectly align on new and full moons (which doesn’t happen every month because the Moon’s orbit is tilted). But phases are merely tricks of the light: no matter how faded it may feel, the Moon is always whole.

Aside from illumination, the Moon offers many boons for life on Earth—namely balance. For thousands of years, it has given humanity a way to mark the passage of time. As I’ve written about before, the Moon’s gravity determines the push and pull of the tides. The Moon stabilizes how much the Earth wobbles on its axis, affecting how the Sun’s energy is distributed around the world; without it, our tilt could vary up to 85 degrees, resulting in a climate of unstable extremes.

All my words are gestures, imperfectly attempting to signal truth. What if we saw everyone that way: as teachers who come and go in each other’s lives, sticks pointing to the Moon? What if we set aside all our pedestals and stopped demanding perfection from one another? What if no one is our one and only? Maybe we’re all just dancing in the dark, searching for something to light the way—animals still howling at a circlet of silver in the sky, if only to say look how beautiful it is.

Over the Moon