Photograph by Alex Cretey Systermans / Connected Archives

WORDS BY FELIX GIROUX

The Jellyfish Elimination Robotic Swarm has one purpose: to wage a precision war on jellyfish.

The army of autonomous robots, known as JEROS, locates jellyfish blooms using integrated cameras. Once its leader spots a target, it assembles reinforcements. Each mechanized sentry switches on its propulsion systems, sucking the translucent sea creatures through whirring blades like deadly woodchippers. The swarm can pulverize nearly 1 ton of jellyfish every hour.

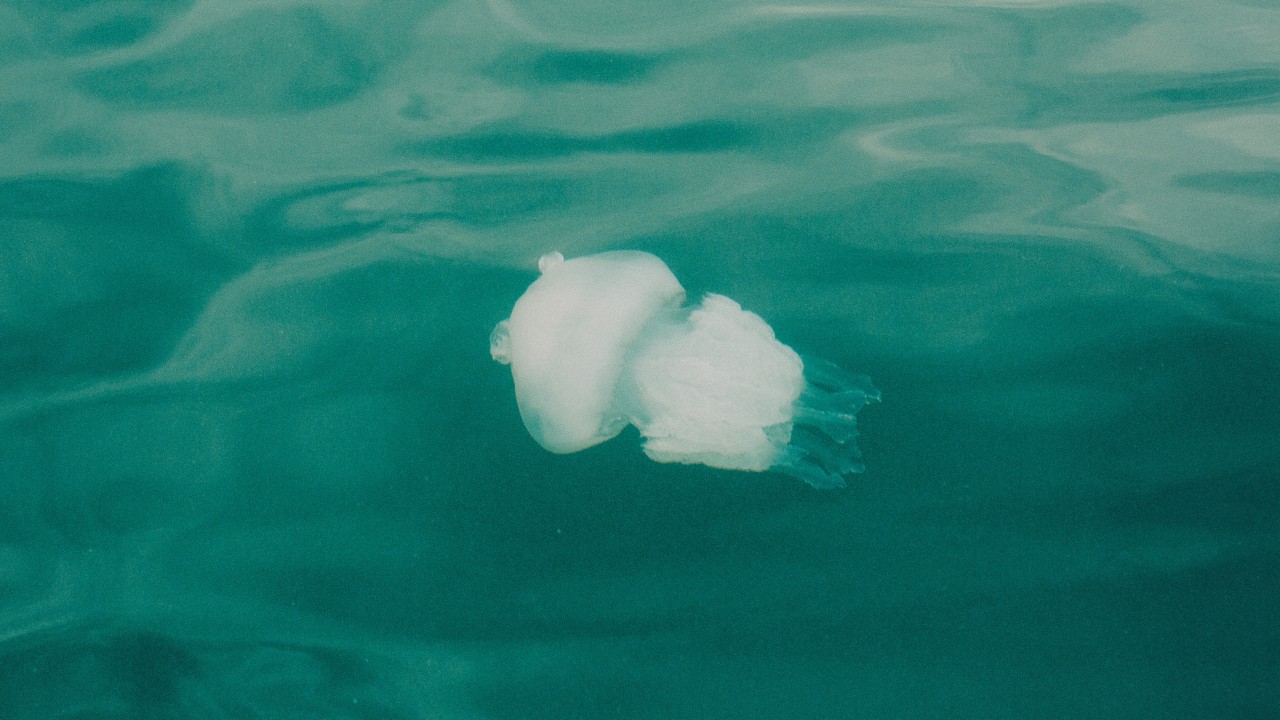

I feel the need to apologize to the jellyfish on behalf of JEROS. I am sorry to all jellyfish. At any moment, as they gently rock in the sea’s currents, multiple coordinating JEROS can be dispatched to destroy entire blooms and turn angelic, aquatic dances into glutinous clouds of chaos.

I am not particularly fond of jellyfish. As a child, I was fascinated with the ones that washed up on beaches. So soft, yet so dangerous. But over the years, I grew increasingly scared of them. The playful naiveté I had as a child was buried deep within me.

Learning of JEROS rekindled my childhood memories. I’m finding a new love and respect for jellyfish. I imagine them floating in throngs, pockets of translucid halos with angel hairs drifting endlessly. Some of them are delicate immortal beings that roam the seas, holding the secret to eternal life. Others hold the power to sting, hurt, and even kill. Gelatinous monsters, aliens, gods. They haunt our dreams and embellish our nightmares. Medusa must have turned the scientists’ and engineers’ hearts into stone for them to design JEROS.

We hunt and kill the jellyfish because we’ve designed a world deemed incompatible with them.

But they haven’t paid close enough attention. Jellyfish can survive blades. By shredding them to pieces, JEROS contributes to their violent propagation. The jellyfish is dead! Long live the jellyfish!

We’re in a war, one we’ve already lost. It’s a paradox. The more we fight, the more we lose. To win would require that we surrender.

We hunt and kill the jellyfish because we’ve designed a world deemed incompatible with them. As we’ve emptied, warmed, and polluted the oceans, we’ve paved a smooth path for their kind to thrive. I’m sorry for the mixed signals, jellyfish.

We say they are dangerous, but the reality is that they’re mostly dangerous to capital—to nuclear power plants, farms, commercial fishing, and tourism. That’s why people pour resources into their elimination.

They may not feel the pain until they’re caught by the robot’s blades, yet my body hurts for them. Our killing machines hurt me even when not targeted at me. I feel connected to the jellyfish. We are translucent and queer bodies momentarily growing to enjoy the spaces made for us. However, the reality is that we’re not safe: dancing in the wrong place and at the wrong time, like Daniel Aston, Derrick Rump, Kelly Loving, Raymond Green Vance, and Ashley Paugh—the victims of the 2022 Club Q shooting. The murdering machines of targeted warfare are out in full force.

Jellyfish warfare is but one example of our necropolitics, how we decide who matters and who is disposable.

Together, we are in the grip of what surveillance capitalism allows to proliferate. Cameras and geolocation technologies always know where we are. Their technologies are precise and targeted, meant to distinguish between their desired forms of life and those they deem harmful. They send them JEROS. They send us alt-right, anti-drag protesters—and the occasional shooter to prove they’re serious.

Jellyfish warfare is but one example of our necropolitics, how we decide who matters and who is disposable. As historian Achille Mbembe puts it, war is our pharmakon—our remedy and our poison. War against jellyfish was inevitable. As we wage war on everything else, we cannot tolerate survivors in our ruins. Thus, we wage war on our ruins, against the jellyfish. I mourn this war. I mourn our need to kill them.

But we are stronger than their technologies of war. Shredding jellies into pieces does not prevent people from being stung. The filaments can more easily sneak through beach nets meant to keep them away, while jelly scraps can get lodged in trawls or filters. When mutilated by the blades, some jellyfish species disperse eggs and sperm all over the ocean. You can try to kill them, but they come back stronger than before. You can shred queer and trans rights, too, but resistance is part of our existence. Queer filaments will always sting back.

Though admirable, the resilience jellyfish showcase is no solace to rejoice in. By disabling the jellyfish, we are only furthering a path of mass disablement. We will end up hurting ourselves. Seas will become monstrous for all who are entangled with humans and jellies. By fleeing one horror, we will only meet another.

Dear Jellyfish, I’m Sorry for the War We Waged