Words by Daphne Chouliaraki Milner

Photographs by Philip-Daniel Ducasse

It’s no secret that fashion has a waste problem.

The industry is estimated to generate over 101 million cubic tons of waste every year, including textile scraps, microplastics, chemical waste, and packaging materials. It’s a number that’s likely to go up in the coming years as the rate at which we buy, wear, and discard our clothes speeds up. It’s also a number that shows just how instrumental throw-away culture is to the fashion system at every stage of the supply chain.

“Waste is a factor of human existence, and as long as we’ve had big business, we’ve had waste,” said Oliver Franklin-Wallis, journalist and author of Wasteland: The Dirty Truth About What We Throw Away, Where It Goes, and Why It Matters. “Fashion is in many ways the business of waste, because it’s predicated on making things obsolete.”

Since the dawn of industrialization, our economy has operated on a linear model of consumption—a “take-make-waste cycle,” according to Valérie Boiten, senior policy officer at the Ellen MacArthur Foundation. Fashion is a particularly egregious culprit. Two percent of the world’s energy goes into producing fast-fashion items, and the industry as a whole is responsible for up to 8% of global carbon emissions, according to the UN Environment Program. Meanwhile, the lifespan of clothes is getting shorter thanks to worsening garment quality and an ever-accelerating trend cycle. On average, a fast-fashion garment is worn just seven times before it is discarded.

The repercussions are dire, with textile waste often burned or dumped. “[Those] pathways all lead to the release of pollutants, including hazardous chemicals, threatening species and habitats,” said Boiten. Microplastics can follow those pathways, too—and since more than 50% of clothing is made of plastic, textiles account for up to 35% of microplastics released to oceans worldwide.

But at what point does a garment actually become waste? “Is it the moment somebody throws the garment away because they don’t need it anymore?” asked Bobby Kolade, founder of Buzigahill, a Kampala, Uganda-based brand repurposing the Global North’s second-hand garments and sending them back to the countries from which they came. “Is it the moment the garment can’t be sold, resold, and re-worn? In which case, is it a resource or is it a discard?”

Here’s just a few of the ways that excess and waste are instrumental to how the fashion system works.

About 40% of the fibers that end up in our clothes are agricultural products.

Crops like cotton are water- and land-intensive. It takes an average of 2,700 liters of water to produce just one cotton T-shirt, about the same amount of water one person would need to drink for 2.5 years, according to a study by the European Parliament. The textile sector is also the third-largest cause of water pollution and land-use degradation. Crops like cotton rely on potentially harmful pesticides to meet demand.

“We’ve come to see waste as the thing we can visualize, like a landfill or items of clothing in waterways,” said Maxine Bédat, founder of fashion think tank New Standard Institute and author of Unraveled: The Life and Death of a Garment. “But if we are creating a cotton garment with the enormous amounts of chemicals that are typically used in the creation of that product, and it’s only used once, then that’s incredibly wasteful.”

Then there are the clothes made from fossil fuel-derived textiles, which account for roughly 60% of our garments. Synthetic fibers like spandex, polyester, and nylon are essentially made of plastic, and the production of textiles alone accounts for 1.35% of global oil consumption, according to a study by nonprofit Changing Markets— more than the annual oil consumption of the entire population of Spain.

Once the raw material fibers are ready, they are transported to the next stage of textile manufacturing: the milling, ginning, weaving or knitting, and dyeing of fibers.

At textile mills, raw fibers are generally cleaned, straightened, and aligned to be spun into yarn. It’s an energy-intensive process responsible for around 57% of energy used by textile manufacturers—34% of the total energy consumption goes towards spinning fibers into yarns and 23% goes towards weaving yarns into fabric. The entire process is fueled by fossil fuels, because factories often rely on coal to power the equipment.

Then there’s dyeing. The vast majority of textile dyes used today are synthetic, many of which don’t biodegrade, and some of which have been linked to cancer and other serious health issues. “The waste we need to be talking about is the waste that goes into the making of dyes and chemicals, which then pollutes rivers and overburdens local waste infrastructure in countries like India and Bangladesh,” said Franklin-Wallis.

After raw materials are transferred to textile and garment manufacturers—another energy-intensive process—the goods are brought to the cutting-room floor. Here, millions of tons of fabric scraps are discarded, which is estimated to account for up to 15% of the total fabric in some cases. It’s often cheaper for brands to spend capital on producing too much than to invest in adopting more efficient practices.

“It’s a deeply wasteful business,” said Venetia La Manna, slow fashion campaigner and cofounder of Remember Who Made Them. “Just 50 years ago, traditional and Indigenous methods of creating and using clothing were zero waste as standard. Today, the scale and pace at which Big Fashion operates is inherently wasteful.”

The fashion industry simply produces too many clothes, and that’s intentional. Brands overproduce to ensure they have enough stock of popular items and to avoid the possibility of missed sales.

It’s a wildly inefficient model that generates between 15 and 45 billion unsold garments of the estimated 150 billion garments that are produced every year, according to a report by WGSN and OC&C. This is, in part, because brands can’t predict what will and what won’t sell. But even in instances where a company invests in data collection and analytics that helps them better understand customer demand, garments are still discarded at alarming rates.

“The current business model is to blame for rampant overproduction,” said Yayra Agbofah, founder and creative director of The Revival, a community-led organization in Ghana that upcycles discarded textiles. “The industry is trying to just make profit, profit, profit—because brands need to appease their shareholders and investors.”

“Fashion is in many ways the business of waste, because it’s predicated on making things obsolete.”

Behind the fashion industry is a multi-billion dollar marketing machine. On social media, hashtag challenges, user-generated video content, live-streamed shopping, and influencer marketing have created new channels for shoppers to spend more—and waste more. Viral fashion does not last long, even less so now that TikTok has paved the way for the microtrend, which typically lasts less than a month. The average consumer buys 60% more clothing than they did in 2000, but they only keep it for half as long, according to McKinsey & Company.

“Brands are relying on Instagram and TikTok algorithms to [manipulate us] into spending more,” said La Manna. “[We’re also seeing] the gamification of online shopping.” The integration of gaming aspects into online shopping has become increasingly common; ultra-fast fashion retailers like Temu and Shein have repeatedly been described as “addictive” by shoppers because of gamified reward programmes, countdowns, and animated elements that keep people on their sites for longer.

“The more time we spend on apps shopping, the less time we have to not only find joy or be with our friends and our communities, but also to get organized and to rally for a system that is fair and just for all of us,” said La Manna.

After a few wears, clothes are often either discarded or tossed in a donation bin. But that’s not the end of their journey.

Unsold and secondhand products from the Global North are routinely shipped to the Global South, where they end up in markets, landfills, and incinerators. “People don’t think of charity shops as part of the waste industry, but the fact is that they are,” said Franklin-Wallis. “We give them things we don’t want, and they make them disappear…With clothing, the majority is sent off to be graded and sorted and sent around the world to places in the Global South.”

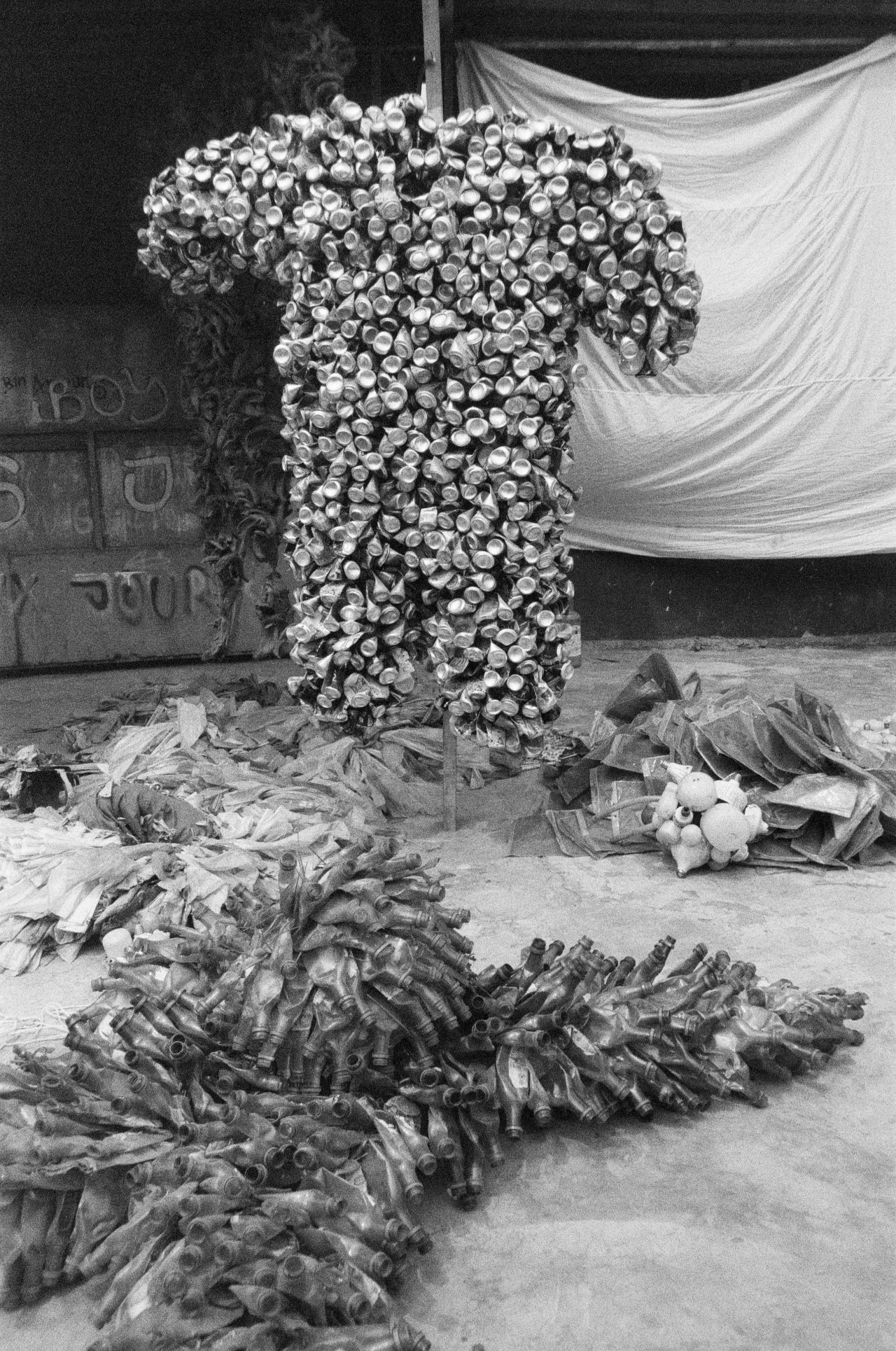

The Democratic Republic of the Congo is one of those places. It’s why Eddy Ekete, who lives between Paris and Kinshasa, decided in 2015 to found the KinAct Festival, an annual street art fair that displays costumes made from rubbish collected from the streets. The motivation, according to Ekete, was to create a platform for local Congolese artists to showcase their talent—and to help manage the city’s waste crisis in the process.

“Western [waste] pollutes more than African waste. African waste [typically] comes from nature: like banana leaves, mango leaves, coconuts, pieces of trees, bark,” said Ekete. “The advantage of our waste is that when you throw it on the ground, it gives life to the Earth. Western waste, on the other hand, is the kind of waste that lingers, that heats up the Earth, that damages everything.”

Today, the KinAct Festival exhibits sculptural contemporary costumes made from both plastic waste and organic matter, and offers street performances and creative workshops to help inspire more people to get involved. “[We are] showing the authorities that there is the possibility of reducing waste with what we do—but we need help,” Ekete said. “We’re doing this with our own resources. We don’t have a lot of space, we don’t have a lot of money, but we have the drive to work with it. That’s determination.”

But the problem Ekete is tackling was started by corporations and consumers in the Global North, and a solution cannot—and should not—be left to local community efforts in the Global South.

An estimated 70% of clothes donated in Europe end up in Africa, according to a 2015 report by Oxfam. For third-party companies known as “textile recyclers” (a misleading term, as many of the garments are not so much recycled as offloaded to dumping sites in the Global South), there’s also a lot of money to be made from buying bales of second hand clothing and selling them to clothing importers.

The trade of secondhand clothing, an industry that’s currently valued at over $230 billion, has played a critical role in the battering of the textile industry across Africa. The repercussions are manifold. Buyers of these clothing bales cannot see the contents before purchase, and much of the bale often turns out to be unusable. The system perpetuates financial insecurity for local secondhand clothing traders.

The fashion industry simply produces too many clothes, and that’s intentional.

“Because the buyers of the secondhand clothing bales can’t see what’s in them, and because much of it [ends up going unsold], they aren’t able to guarantee they’ll even make back the money they’ve invested in purchasing the bale to begin with,” said anti-fast fashion advocate Yvette Tetteh, who swam the length of Ghana’s Volta River to draw attention to waste colonialism. “In other words, they start off in debt.”

As legislation like the EU’s mandatory and harmonized Extended Producer Responsibility policy is being debated, there are growing calls by advocates to ensure that equity and justice are built into those laws. Currently, when made, EPR payments by brands often end up funding waste collection in the Global North without necessarily directing payments to countries like Ghana or Kenya, where the clothes end up. The pressure on frontline communities, who are made responsible for processing and discarding waste that’s not theirs, is enormous.

Kolade describes the process of sending bales of clothing from Europe to Africa that are embedded with unsellable clothing as “smuggling” waste. “We’re not saying that the trade should be banned…There are too many millions of people on the continent who rely on the trade for their livelihoods. The issue is the smuggling of waste—the whole system needs to change.”

The fashion industry’s waste crisis is, in many ways, a crisis of responsibility; of brands in the Global North refusing to take accountability for the waste that they produce, leaving communities in the Global South to clean up the mess.

The system is upheld by the industry’s failure to account for waste management costs from the get-go. “For too long, it’s been too easy to incinerate leftover stock,” said Christina Dean, founder of Redress, a nonprofit organization focused on accelerating the industry’s transition to circular fashion. “Now, there’s a reputational risk of incineration and some legislation in place—those two things should put more pressure on a mildly adjusted cost structure.”

But many feel that crucial legislative milestones are being implemented too slowly. The EU’s EPR policy is still being negotiated in the European Parliament, and New York’s groundbreaking Fashion Act—whose drafting was led by Bédat and which takes aim at, among other things, chemical mismanagement in fashion’s supply chains—has yet to pass.

For communities in Ghana, the need to restructure the industry with equity and justice at its core could not be more urgent. The Revival’s Agbofah said that it’s the industry’s deliberate refusal to take responsibility for the extent of its waste production that has caused large swathes of Ghana to become dumping grounds.

“I am tired of conversations. There have been so many, and none have led to action at the pace they should,” said Agbofah. “Much of the policy has goals 10 years from now. In that time, we’ll see mass destruction…Change can’t come soon enough.”

COSTUMES Eddy Ekete, Bestaguy Bayoka, Luc Masala, Putela Tantine TALENT Bonaza Amigo, Bestaguy Bayoka, Man Mpote, Tumba Lion, Thomas Ntsuka

This story first appeared in Atmos Volume 10: Afterlife with the title “Waste Not.”

When Did Throw-Away Culture Become Big Business?